Conducting a High-Rise Mock Disaster Drill

DISASTER MANAGEMENT

The idea of conducting a mock disaster drill for our high-rise had been kicked around for a number of years. However, it took a deadly fire in Los Angeles’ tallest building, the First Interstate Bank Building, to make such a drill a top priority.

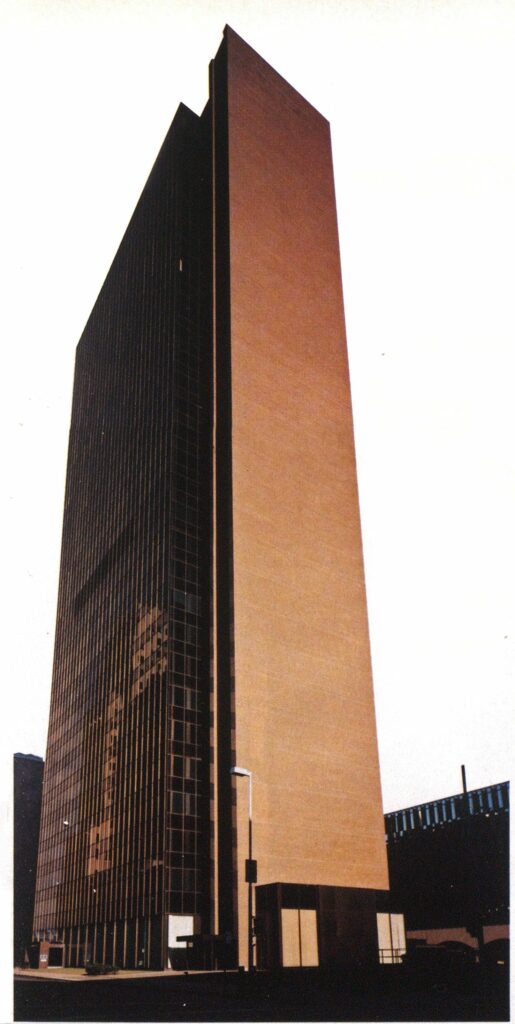

Our facility is the Fiberglas Tower, a 30-story, mostly glass-and-steel structure in the heart of downtown Toledo, Ohio and the corporate headquarters of Owens-Corning Fiberglas. It is owned and operated by the Mid-America Management Corporation; Owens-Corning Fiberglas is the major tenant, occupying 28 of the 30 floors. It is a well-managed facility with an outstanding safety record. There was, therefore, no urgent need to conduct a mock disaster drill. Also, there never seemed to be enough time for all the projects that should be done but weren’t really the most pressing.

Our first step toward deciding to have a drill was to seek input from associates and advisors. We asked them: Are we ready for this? Can it be done? What problems do you foresee? Can we be embarrassed by failure? We discovered that there had never been a drill using a high-rise facility nor a drill of this magnitude in either the city of Toledo or in northwestern Ohio.

Photo by Mark Oberst.

After gaining peer support for the project, the next step—and probably the biggest hurdle of all—was convincing management to go along with the idea. Eventually they agreed despite the possible risk to the company’s and their own reputations if all did not go well.

The final obstacle was to convince the building owner to let us hold the exercise. The owner wouldn’t get much credit if the drill was a success but would probably get a lot of heat from the home office if the drill was a failure. Most of all, there was always a chance of damaging the property—a firefighter’s ladder penetrating the skin of the building or an air cylinder or a soiled uniform brushing up against a decorative piece of art or expensive fixture. This is probably why more mock disaster drills are not conducted. There is much at stake, and to some, maybe not a lot to gain and much to lose—especially since it’s much easier to take the attitude, “This really couldn’t happen to us.”

This is where a good working relationship and a spirit of cooperation come into play. Understanding the building owner’s dilemma is a must. By agreeing to make the owner an integral part of the planning process, by giving it veto rights regarding any part of the project, and by giving it the power to stop any actions during the drill that would endanger the property, we won owner support for the project.

The next step was to present the idea to the Toledo Fire Division. The members had never really participated in a high-rise drill of this magnitude and had no idea what to expect. They certainly did not need local “bad press” and costly overtime expenditures resulting from a mere “practice drill.” They also were in the process of implementing new foreground command procedures to the national Incident Command System and felt that it was not at a stage of development for a drill of this size. In addition, they had a manpower shortage and were reluctant to participate.

(Photo by Randy Hughes.)

Days turned into weeks and weeks turned into months, and the Toledo Fire Division did not respond to the initial offer. After nearly three months, we approached another local agency about the drill. We contacted the area director of the Regional Emergency Medical Services of Northwestern Ohio (REMSNO). A unique relationship exists between REMSNO and the Toledo Fire Division: Even though REMSNO paramedics are members of the Toledo Fire Division, they come under the authority of REMSNO. Because of this dual authority, a degree of healthy competitiveness exists between the two groups.

REMSNO immediately jumped on the bandwagon. They are always on the lookout for such exercises, and this one, never tried before, sounded especially inviting. Once REMSNO agreed to participate, the Toledo Fire Division joined in as well, now more confident in its ability to implement the ICS for such a large-scale drill and more willing to test that expertise.

PLANNING MEETINGS

Most planning meetings were held at Owens-Coming corporate headquarters in the Fiberglas Tower. Meeting on neutral territory defused the competitiveness between REMSNO and the fire department and fostered a goal-oriented atmosphere that lasted throughout the entire project.

Our Corporate Fire Protection Engineering Department obtained a tape of the First Interstate fire from the Los Angeles City Fire Department. Showing this tape helped us establish a sense of urgency. The tape was made available to all organizations that would eventually participate in our drill, and it was the perfect stimulus for selling the project.

The original plan was to conduct a mock disaster drill that would involve the local fire department and REMSNO, giving them the chance to practice their emergency skills in a high-rise facility. We wanted mock casualties to involve one of the local hospitals as well.

At the second organizational meeting, representatives of other emergency organizations attended, as word of mouth aroused interest in the project. A representative of the Hospital Council of Northwest Ohio explained to those present that in order to maintain credentials, local hospitals were required to participate in at least one emergency drill per year. Thus the council asked that all nine local Toledo hospitals be involved.

A representative of the local disaster emergency medical team (DEMET), an organization of specially trained medical professionals formed as a result of the Mexico City earthquake catastrophe, thought our mock disaster drill would be the perfect opportunity for the two recently formed local DEMET teams to demonstrate their skills. They planned to bring a contingency from Washington, D.C. to monitor the event.

The County Civil Defense Organization, now called Lucas County Civil Defense Emergency Management Agency, offered to conduct an exercise on paper that would entail county, state, and federal agencies. Our mock disaster drill was quickly taking on large-scale proportions, as more and more people asked to participate.

Plans included the following:

- We notified the news media in advance to solicit their support and avoid adverse publicity that would be detrimental to the project.

- We secured public relations support to represent all involved parties and to handle a press briefing, news releases, a media center, and the development of media restrictions.

- We asked the City of Toledo Police Department to cordon off streets leading to the disaster scene and maintain order.

- We enlisted the participation of 35 of our security/safety floor coordinators and 35 student nurses from nearby Mercy Hospital as victims. (The nine hospitals involved would require seven to eight victims each to test their emergency preparedness procedures. This would require a cadre of approximately 70 victims.) Victims would be scattered throughout the upper fire floors and in the stairwells.

- Two moulage teams would make up the victims to look injured. Victims were coached and prepared to act the part—with fake burns, broken bones, and so on.

- The community REMSNO vehicles and private ambulances would be taxed to their limit. Added transportation would be needed to take the nonseriously injured to the hospitals. As in a real disaster situation, city buses would be put into operation. Transportation would also be needed to return the victims to the Fiberglas Tower and their parked cars after the exercise.

- Hundreds of medical personnel would be standing by at hospital emergency rooms. They would accept the victims and treat them as though they were involved in life-anddeath situations.

- We developed an emergency code for the participants to identify

- any real injuries resulting from the drill.

- To chronicle the event, all agencies involved planned private taping to develop later as a training film. Eventually 11 tapes would be condensed for this purpose.

- A team was established to review how the participants reacted to the event. Local city officials and other VIPs who wished to review the drill were added to the increasingly large list of monitors.

- Owens-Coming Fiberglas would enlist the support of most of its Toledo Facilities Services crew to remove art pieces and other valuable items from each floor to avoid damage. Designated elevators used by firefighters would be lined with cardboard to protect them from damage and soiling.

- Personnel would conduct cleanup after the drill, removing victim moulage and soil from participants’ uniforms and equipment from walls and carpeting. Considerable manhours and approximately $2,700 would be spent on preparation and cleanup operations.

- Both the building owner’s representative and I were designated “controllers.” We would halt any activity that we deemed detrimental either to the building or to the operations of Owens-Corning Fiberglas. Because of excellent planning, “controller” intervention was never needed during the drill.

- “Relatives” of the victims would jam the Ohio Bell and the American Red Cross telephone lines to obtain information on their loved ones.

A total of 11 preparatory meetings followed the initial program establishment. These did not include the many informal visits that fire department command officers and paramedics who would be involved in the exercise made to the facility.

By the time the drill was conducted, there would be no building in the city of Toledo with which the Toledo Fire Division was more familiar, nor would there be any facility more prepared for an emergency situation. The many meetings turned out to be essential for planning purposes and for controlling the many details, new ones of which sometimes developed daily.

In order to prevent disruption of Owens-Corning’s and the building owner’s operations, the drill was planned for a Sunday morning. This would be the least disruptive time for other downtown merchants and for everyone concerned.

MASSIVE DRILL

For realism, we decided to stage the fire on an upper floor in the freight elevator vestibule, where employee coffeemakers are located. The maintenance/mechanical equipment areas are on the 13th floor of the building. The 12th floor was the staging floor. The 14th floor became the fire floor.

The fire scenario was as follows: An employee working during off-hours put on a fresh pot of coffee at 6 a.m. Not thinking, the employee failed to turn off the coffee unit when he left at 8:10 a.m.

The pot boiled dry and overheated, and at 8:50 a.m. a fire erupted. The contents of a wastebasket quickly ignited and flames rapidly spread to the cardboard cartons sitting next to the freight elevator near an adjoining mail chute.

At 8:53 a.m. the first smoke alarm sounded. The lobby security officer identified the alarm and proceeded to the 13th floor using the nearby passenger elevator. He went up the stairwell to the 14th floor. At 8:56 a.m. he arrived to find the entire freight elevator vestibule area engulfed in flames and volumes of dense smoke quickly spreading onto the floor and into the main office area. He immediately radioed to the lobby security console for help.

The Toledo Fire Division logged the incoming emergency call at 8:57 a.m.

The actual drill lasted approximately 1 ½ hours. The following is a stepby-step account of how the drill unfolded.

At 7 a.m. organizers of the exercise and victim participants began to arrive. Victims were told to act in a variety of ways, from passive to hysterical to unconscious. Symptoms and injuries were identified using an index-card system.

Monitors and observers were instructed to remain “invisible” and not to interfere. They were identified by red arm bands, as were three camera crews to allow them free access to the facility.

The victims were placed in building stairwells, on the fire floor, on the floors above and below the fire floor, and in evacuation areas.

The fire was then staged. One of the organizers used artificial smoke to activate the smoke detectors in the 14th floor freight elevator lobby. All elevators were immediately recalled to the lobby and placed in manual operation.

At 8:57 an attempt to call the fire department using the autocall system failed. The security officer on duty manually notified the fire department. The first alarm was dispatched and fire units arrived at the Fiberglas Tower within four minutes and included three engines, two trucks, one rescue squad, a medical unit, an air unit (SCBA), a deputy chief, and a battalion chief.

The first engine arrived on the scene and reported it would investigate the alarm coming from the 14th floor. The officer on the first engine established a command in the lobby at the security console. A fire crew went to the 13th floor to investigate the alarm using the service elevator in manual mode. They proceeded to the 14th floor by stairs, encountering several people evacuating the area. They found smoke in the stairwell and some injured people.

Firefighters were told by some injured that others were trapped on the 14th floor. Also they received reports of heavy smoke and fire on the 15th floor.

The fire attack team notified command of the situation. Command then requested a second alarm and additional medical units and private ambulance companies.

As the fire progressed, the deputy moved the command post to a building across the street from the highrise. He informed all responders that the high-rise procedure would be followed. The command post included a police command officer, a fire division medical supervisor, a liaison officer, a public information officer, a safety officer, news media, an OwensCorning spokesman, and the building owner’s representative.

(Photos by Randy Hughes.)

When it was determined that additional medical assistance would be needed, the on-scene EMS coordinator requested that the medical disaster plan be activated.

The Toledo Police Department responded and established traffic control in the area of the high-rise building. They rerouted traffic and set up police lines around the building. A police command officer reported to the command post to maintain liaison and communication with police operations personnel.

Victims were taken to two triage areas—one on the 11th floor in the fire building and the other in an adjoining building arcade on the ground floor. Access to this building is through a connecting (protected) passageway. DEMAT teams consisting of doctors, nurses, and other emergency medical personnel immediately began to assess and treat the victims. {Note: Toledo is the only city in the country at this time to have a national disaster medical system without having a military hospital.)

Ambulances were staged one block from the fire scene. A medical transportation officer directed transportation of the victims to the hospitals. Transportation was provided by advanced and basic life support units. Two community buses were put into service by the Toledo Area Regional Transit Authority for the walking wounded.

Participating hospitals went so far as to treat victims as actual patients. Some victims were even taken as far as surgery before being released.

After the initial alarm, all arriving fire crews came into the high-rise using a remote underground entrance (normally a delivery entrance) to avoid possible injury from falling glass and debris.

Extent of the fire was found to be limited to the 14th and 15th floors. The entire building was checked for extension. The fire was brought under control and extinguished at 10:30 a.m., after burning for 1½ hours.

The Toledo Fire Division has a preplan of all major buildings and facilities. The preplan became an integral part of the overall operation. Building maintenance brought key information relative to building design and air handling equipment to the command post, where it was reviewed.

A critique at REMSNO headquarters immediately followed the event. Participants included the Toledo Fire Division, private ambulance companies, REMSNO, the Hospital Council of Northwest Ohio, DEMAT teams, and the Toledo Police Department. A second critique session was conducted several days later by Owens-Corning Fiberglas and Mid-American Management personnel for a debriefing of the victims.

Those involved in the project included 70 firefighters and command officers; 20 paramedics; 18 ambulance attendants and drivers; 70 victims; 40 monitors; two emergency medical teams; 18 maintenance personnel; four moulage team members; and medical personnel from nine hospitals.

LESSONS LEARNED

The following is what the drill taught us:

- The size of the drill was nearly overwhelming and totally exhausted everyone involved in the project.

- The new DEMAT teams made a significant impact in caring for the injured.

- The floor security/safety coordinators and Mercy Hospital student nurses turned out to be a most valuable asset, as they were able to provide a new dimension in assessing patient care.

- The building’s autocall system did not work. It has since been repaired.

- Police would not allow emergency buses past barricades as they were unidentifiable. This has led to identifi-

- cation cards being placed in bus windows.

- There was delay in setting up a transportation officer for EMS. There was also poor communication between command and the staged ambulances. These problems are currently being addressed.

- There was an unequal distribution of victims to two of the participating hospitals: One hospital received 12 victims while another received none. Better communication and traffic control by the transportation officer are needed.

- Outlying EMS units who responded had difficulty locating inner-city hospitals. We are considering providing maps.

- Some telecommunication systems in the EMS units were found to be inoperable. This may have been attributed to systems overload.

- We would need much more fire service personnel for a real incident. Fire crews were overtaxed (this was a manpower constraint).

- Fire crews were confused as to

- how to operate elevators in manual mode. This appears to be due to conflicting orders initially.

- Emergency crews failed to collapse revolving glass doors early. Instead, they used secondary entrances. Had revolving doors been immediately collapsed, speedier entry and exit would have resulted.

- It is important to have an emergency code to identify actual emergencies during such a drill. This code was established during the planning meetings and was used during the drill when one firefighter collapsed.

- The Siamese connection, located in front of the high-rise, had debris inside that had to be removed. Regular inspection should eliminate this problem.

- Floor plans were missing on each floor. They now are provided.

- The newly formed DEMAT teams arrived with no communications equipment and were unable to communicate with others in the exercise. This is being addressed.

- Building maintenance personnel did not immediately shut down airhandling equipment as planned. This has been addressed.

- NDMS personnel arriving at the scene entered through the fire building. They did not report to EMS staging or the command post for direction or assignment. This, as well as provisions for communication, will be addressed through ICS training.

- There was a lack of formal identification of EMS personnel for triage, transportation, and so on. This is being addressed through procurement of identification vests.

The enormous success of the event was due primarily to effective planning and the extraordinary cooperation between the public and private sectors. It would have been impossible to conduct such an event without this type of cooperation.

As a result of the mock disaster drill, we will be much better prepared if such an unfortunate disaster ever occurs. What about you—are you prepared for a disaster?