D.O.A. at the Fire Scene

features

INVESTIGATION

An incident involving a fire-related death in a tenement apartment was determined to be incendiary in origin. The deceased was found in a hall closet with a wire coat hanger wrapped around his neck. Obviously, this was arson intended to cover up a homicide. However, it was not so clear to a law enforcement officer. “The man was cooking at the stove, right? He set fire to himself accidentally, right? In his confusion, he ran from the fire and mistook the hall closet for the hall door, right? While in the closet, he struggled to get out and hung himself with a wire coat hanger, right!”

Wrong.

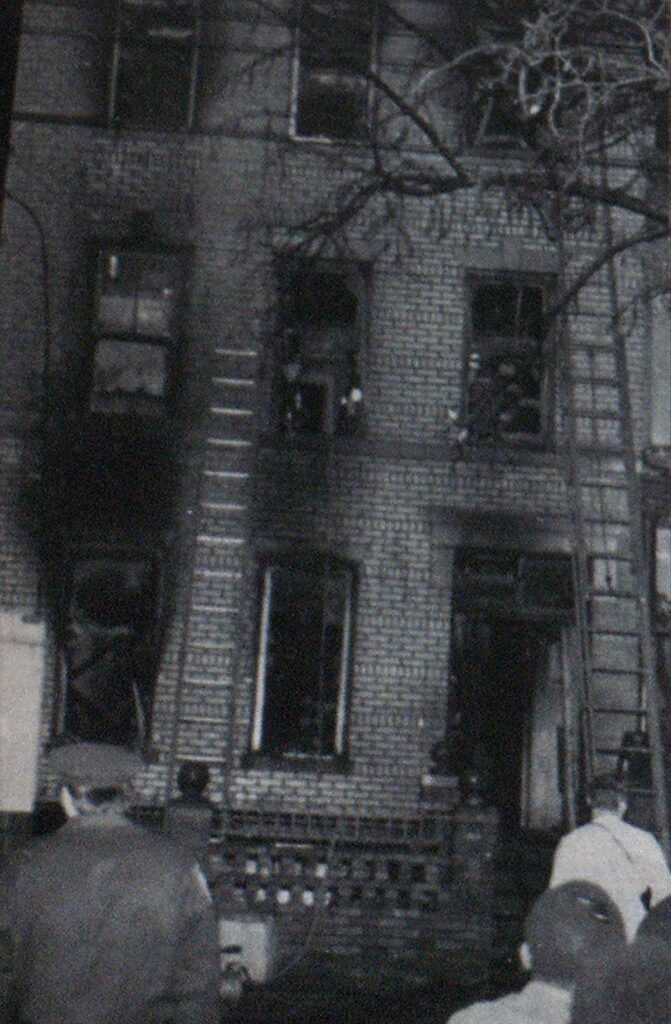

Official FDNY photo by G. S. Tufte

Even a novice fire marshal could see that either this detective’s lack of ability to analyze a fire scene or his reluctance to meet his responsibilities as an investigator caused him to grossly misevaluate the evidence of his senses.

The most important investigation at a fire scene is a fire death, whether it be an accidental or incendiary fire. In performing firedeath investigations, it is important to recognize that you are actually conducting two complete investigations, the death and the fire. And the second is not necessarily the cause of the first.

Whether you are a firefighter, a fire marshal with police powers, or a fire investigator limited to origin and cause, if you recognize, document, and report what you see at a fire scene, you will be an invaluable asset in determining why, how, and, possibly, by whose hand a fire was begun.

ACCIDENTAL OR INCENDIARY FIRE

As is always the case in any fire, your first task in investigating a fire death is to determine where and how the fire started. If you are able to rule out all of the possible accidental and natural causes of a fire, then, and only then can you consider the fire suspicious.

And only after the fire’s origin and cause is established without any doubt can you then proceed to do the investigation of the fire death (D.O.A. or dead on arrival). The New York City Fire Marshal’s Office has established rules and procedures for a D.O.A. investigation, many of which are followed in this article.

Whether a fire is accidental, natural, or incendiary, we must determine whether the deceased was a victim of the fire or whether he was deceased before or irrespective of the fire. The focal differences between accidental death, suicide, and homicide investigations are far-reaching and complex, but the object of your inquiry for all of them will be the same. You are trying to find an answer to the question: Why didn’t the victim escape the fire?

The information you are seeking varies slightly from one area of the country to another, but you are basically recording the address, alarm number, time of alarm, highest alarm, description of the building, etc. Also, determine if there are any existing violations listed for the building with the fire department, building department, department of health, or any other agency.

As a general rule, we can state that in an ordinary house fire without massive destruction or collapse, the location at which you find a body is the location at which the person died. Since man’s natural inclination is to flee from fire, you want to determine if that is what the victim was doing as he succumbed to flames or toxic products. If the victim was not found in an attempt-to-escape position, we must ask ourselves why.

Official FDNY photo by G.S. Tufte

Some of the reasons may lie in building violations, barred windows and/or exits, illegal occupancy, lack of a secondary means of egress, absence of smoke alarms and/or sprinkler systems, etc.

To determine the role, if any, that possible violations may have had at a fire, you must determine the physical conditions of the building as discovered by the fire department on their arrival. This should include the status of doors, windows, exits, etc. Learn the amount of fire found and how it extended. Ask if the fire’s path of travel was consistent with our knowledge of fire spread. If not, why not?

NATURE OF DECEASED

Before you can proceed with your investigation, a profile of the victim has to be developed. Obviously, you need to know his or her name, address, sex, age, income source, employment, and marital status.

Physical factors

Were there any unusual conditions intrinsic to the victim that may have contributed to preventing his escape?

Was the victim ambulatory? Did he smoke or drink? Did he take medication, drugs, etc., that might have affected his perceptions or capabilities? Did he have any coronary or pulmonary problems before the fire?

Look in the medicine cabinet for medication and doctors’ names to help you determine what type of treatment the victim was receiving. Medication in the vicinity of the bed or in the area where the body was found should also be noticed and noted.

Mental and emotional factors

Was the victim senile, confused, depressed? Did he have a past history of mental illness? Did he attempt suicide in the past? Was there a note found?

Were there any previous fires at this location? Did they involve the same individual?

Most of these questions may be answered by friends, neighbors, and relatives.

ON-SCENE QUESTIONING

Since most fire investigators do not arrive at the fire scene until the incident is under control, it is essential to question emergency personnel at the scene as soon as possible. The longer you wait, the less reliable is the information you will obtain. Of primary concern in your questions is the location, position, and appearance of the body.

As previously mentioned, location may indicate that the person was or was not attempting to flee; the deceased may be found inside an exit door, at a window sill, or in a bathtub, attempting to prevent the fire and smoke from affecting him. Children are often found hiding from the fire threat in closets and under beds.

Although most fire incident report forms do not ask us to record information such as the condition of dress of the deceased, what the victim is wearing could be very important. If you have a fire at 3 AM, and the victim is found in his residence, in his bed, in street clothes as opposed to bed clothes, this could make all the difference in the world to your determination of how this fire began, and how the victim died.

We had several cases in which the status of the victim’s dress or undress significantly altered the meaning of the case. In one, a naked woman was discovered dead on top of the bed covers on New Year’s Eve in a northeastern city. Although she had allegedly died of smoke inhalation, this unorthodox manner of sleeping in the winter led us to look further, seeking out autopsy reports, interviewing firefighters, etc., ultimately leading us away from the conclusion of accidental death to a homicide investigation.

TREATMENT OF THE BODY

A D.O.A. at a fire gives all firefighters a sense of loss and, in some ways, of failure, no matter how impossible the odds are. There is always an uneasy silence at the scene of a fire death and an urgency to put the body in a body bag and remove it. These feelings of urgency can hamper the thoroughness of your investigation.

In some municipalities, the fire department is required to leave the body in place until the fire investigator or the medical examiner arrives. When this is the case, firefighters should be instructed to leave the victim exactly where he is found, unaltered. A cover can be carefully placed over the body to prevent any further water and debris from falling on it until the medical examiner arrives at the scene.

If, however, the body has been removed to the Office of the Medical Examiner before your arrival at the scene, then you should go to his office and attempt to inspect the body before the autopsy.

When you are charged with transportation of the body, care should be taken not to injure the deceased further. This is important in order for the medical examiner to accurately determine if a broken nose, bruises, etc., occurred before or after death.

When moving the body, care should be taken to first place it in a white sheet so that you can catch any trace evidence that might otherwise fall away from the deceased. The clothing under the victim should also be placed on the sheet, between the victim’s legs so it won’t get lost.

Every effort must be made to retain or recover the teeth or dentures from the fire scene as these can help in victim identification and/or may offer a clue as to the cause of death (see “A Manufacturer’s Defect or Murder?” FIRE ENGINEERING, January 1986). If a body is incinerated, these items may be underneath the victim, in the clothing or elsewhere. Teeth parts are often very loose in incinerated bodies and can fall away at the slightest movement.

All artifacts near the body, such as eyeglasses, belt buckles, wigs, etc., should also be included in the transport.

PHOTOGRAPHING THE FIRE VICTIM

Photographs should always be taken at a D.O.A. investigation and the fire scene should be well documented. Start by taking exterior photographs of the building. If you arrived during firefighting operations, photograph the exterior smoke patterns and path of fire. After the fire is extinguished, door locks, exterior entrance and interior occupancy doors should be photographed along with all relevant windows and emergency exits. These photographs will document any visible violations and the secured condition of the building.

Your photographs should follow a logical progression. For example, they should begin in an area of no fire or smoke damage, progressing to a mid-line burn pattern on the walls, to the area of origin, showing the most severe damage, and, finally, to the victim himself. If the body was removed before your arrival, the exact location where it was found and the immediate surrounding area should be photographed and a detailed sketch made of the scene.

The body should be photographed from several different angles. Photographs and sketches should also be made after the body has been removed. When photographing, pay particular attention to signs of bruises, broken bones, or any marks of violence. Photograph any charring of the skin or appendages that are burned off.

THINGS TO RECOGNIZE

Notice if there are any unusual burn patterns on the body itself. By this I mean isolated burning of a limited area, burning in unrelated patches, or unrelated superficially burned areas. Many times, this indicates that a flammable liquid may have been applied to the body.

Since the human body is composed of 97% water, it is essentially flame-proof. Therefore, it is usually quite difficult to dispose of a homicide victim by setting fire to a building.

A clothed body is destroyed in a fire more rapidly and more completely than an unclothed one because the clothes act as a wick, providing for more complete combustion. Also, the body of an obese individual is consumed more thoroughly than that of a lean person since the heat of the fire burns through the skin, exposing the body fat, which is combustible.

Official FDNY photo by G. S. Tufte

If a body has been exposed to fire, it is usually found in a pugalistic position. It is also not uncommon to find that the body has been charred and singed. Charring of the skin usually means that the person was dead at the time of the fire. The skin may have split; there may be long bone fractures and skull fractures with the skull exploding outward. You may observe protruding tongues; loss of tissue; small steam blisters; redringed blisters filled with fluid; soot in the mouth and nostrils, which generally means that the victim was alive at the time of the fire and inhaled the products of combustion; and a cherry-red appearance. Blistering of the skin could be preor post fire.

Carboxyhemoglobin saturations (carbon monoxide poisoning) exceeding 30% to 35% usually (unfortunately not always) produce distinct cherry-red colored dependent lividity. (Dependent lividity is the color visible through the skin on all of the lower parts of the body, to which the blood has flowed due to gravity.)

If the head-only area shows significant damage by flame, it may be an attempt to obliterate the identity of the victim, and arson should be suspected.

Other things you may want to look for if you suspect that you’re dealing with an arson-homicide include:

- Bite marks. Recently, bite marks have been accepted as evidence to identify suspected assailants. Bite marks can be indicators of a homicide, possible sexual abuse, and/or child abuse. Our job is to recognize, document, and report this type of evidence if it is readily discoverable by visual examination. It is the job of the medical examiner and/or the forensic odontologist to further investigate and interpret this type of data.

- Stab wounds. Stab wounds through clothing are usually a sign of a homicide. Look for these holes if the clothing is still on the victim. Examination of the wounds under the clothing can sometimes be made without disturbing the evidence if care is tak-

- en. But, when in doubt, wait for the arrival of the forensic pathologist and point out your suspicions.

Defense wounds of the hands and forearms where a person tried to defend himself are also easy to detect and should be recorded.

Superficial cuts could be related to sex homicides (torture), or they could be initial attempts at suicide, but again, recognize, document, and report.

- Gunshot wounds. Volumes have been written on the subject of gunshot wounds. It has become a forensic specialty within a specialty. The fire investigator’s role, if possible, is just to recognize that there may be a gunshot wound, and I think we would all recognize the obvious gunshot wounds. The smaller caliber gunshot wounds are more difficult to discover, especially if the area of entry was an ear eye. or a head wound under the hairiine.

CAT ASTROPHKES

At catastrophies where there are one or more D.O A s the bodies should be protected and not moved whenever possible. If there are body parts, they should be left in the same position and location that they are found and. where possible, numbered consecutively This will enable the medical examiner when performing autopsies, to relate the bodv parts to each other and aid in interrretmg and identify ing what parts belong to what bodies. The bodies, and body parts should be photographed where they are found.

WTERPRET1NG THE EVIDENCE

I once did an investigation in a civil product liability case that arose out of a body found in a burned vehicle. The local officials determined that the deceased had died accidentally as a result of a defect in the automobile which had caused the fire. An autopsv was not performed, but some slides were made and X rays were taken.

When I examined the on-scene photographs, I noticed that the body was incinerated to the extent that there were only white bones left. At a cremation, 2.000F of direct heat is applied to a bodv that is being vented and rotated as it burns. This type o* Hen: produces white bone—not the heat from an ordinary car or house fire.

An X ray of the mandible of the deceased showed that it had suffered a severe vertical crack and dislocation, and that the rear teeth were missing. The cracked mandible was dismissed by the coroner as heat fracture.

With regard to the missing rear molars, it is interesting to note that teeth burn from the front to the rear, and from outside inward. The rear molars usually never burn because of the protective padding of the jaw muscles. Even in a crematorium, they have to be ground up. Since the rear molars in our victim w ere missing, it was a clear indication that the jaw had beer, broken prior to the fire and that the rear molars had been knocked out.

Obviously what we had was not a civil product liability case at all. but a homicide. In arriving at this conclusion we simply did what we are trained to do at a fire investigation :.e if all of the accidental and natural causes of the fire have been ruled out and the physical evidence shows that the car fire was incendiary we can conclude that we have a homicide. Once this has been establishedthen the motive should be established.

Am I asking you to be homicide detectives? No. Give it any title you like DO A. investigation. fine scene analysis it doesn t matter what, but most police officers and local coroners do not have the experience vou do to perform a fire death investigation at the scene of a fire. All the facts that you develop are not in conflict with any one. but merely enhance the chance of ever, one to do a better job.

As part of your investigation, who discovered the fire is probably the most important question you will ask .As usual the name address, sex. age, telephone number and employment must be recorded. Also, you want to know the relationship of the deceased to whoever discovered the fire.

You want to find out what actions this person took prior to and after his discovery of the fire. You should also record the circumstances surrounding the discover* .

Just as the first person to discover the fire is vital to your investigation. so too is the last person who was at the point of origin prior to the fire. What was his reason for being there? What actions were taken there, and what were his actions prior to the time of the fire?

Also find out who were the last people to see the deceased alive. What were their relationships to the deceased? What were their last conversations with the deceased?

INSURANCE

As fire investigators, you will be exchanging information with the insurer of the deceased for any of a number of reasons, including securing data that they may have which you don’t—and learning a possible motive.

In the category of fire insurance, we want to know the carrier, policy number, amount, date issued, and recent change of beneficiary. If the insured has more than one policy, list each of them separately.

In the category of life insurance, we also want to know the carrier, amount, date issued, recent changes, and beneficiary. Here, too, if there is more than one policy, list each of them individually. Also, find out if there is a double indemnity clause in any policy.

In a recent case, two children were found dead at a fire. One was found sitting in a chair, and the other one was found on her back with her arms and legs extended. The positions of the bodies and the circumstance of the fire were extremely suspicious.

One of the parents of these two girls worked for an insurance company. A routine check of her policies showed that 30 days prior to the fire she had taken out life insurance on her two children with an insurance carrier different from the one for whom she worked.

This new policy included a double indemnity clause. It was through careful questioning of this woman by the fire investigators that the suspicious nature of the fire was confirmed.

SUMMARY

In most large cities, there are teams of homicide investigators, crime scene units, and medical examiners that make our job of investigation easier and reduce our involvement to that of recognizing, documenting, and reporting what we see at a fire scene. Handling of the body itself or of the area where a crime was possibly committed should be left to these experts.

In smaller municipalities, however, this type of sophistication and division of labor is not always available. Who, then, will do it? Only you! Your expertise of investigating and determining cause and origin is often the greatest level of expertise available in the area, and your observations, notations, and documentations at the fire scene will be not only invaluable, but often the only ones made at all.

No one likes to do this kind of work. Out of fairness to all parties, your conscientious investigations could make the difference between whether a beneficiary collects insurance or not, and whether a homicide is detected or goes unnoticed—and unsolved.