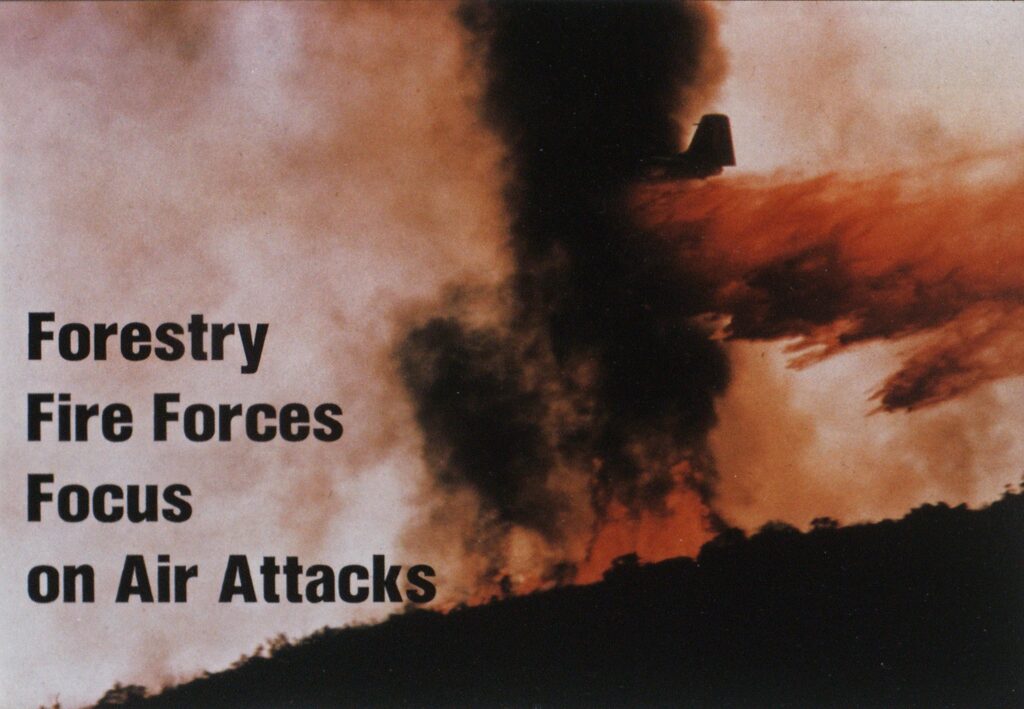

Forestry Fire Forces Focus on Air Attacks

FEATURES

APPARATUS

Photos by L. W. Elias

California’s fire control needs are special. With ideal fire conditions existing almost six months of each year over a large, diversified area, California’s fire response capability must be high. And it is—literally. An important part of California’s firefighting forces is an air force consisting of seventeen Grumman S2F anti-submarine patrol aircraft, four B-17 bombers, and seven helicopters— all converted to dump extinguishing agents on spreading wildfires.

The military retains title to this airborne firefighting force which is leased to California. The state, in turn, leases the planes to private operators during the fire season (normally mid-June to mid-November).

Rapidly spreading fires in remote areas require response in kind, and aircraft have proven to be essential weapons for these quick attacks. Lennie Baker, heading the air attack group in Ramona, CA, says his planes can be over the scene of a fire anywhere in his response district (San Diego county) within 12 minutes after receiving the call.

Speed, mobility, accuracy, and load capacity of the air tankers notwithstanding, ground troops remain indispensable. The California Department of Forestry (CDF) has 4,400 state personnel during the fire season, ready to drive its 219 pumpers, man the lines, and direct manpower available from a pool of about 2,000 prisoners or wards in the state’s Conservation Camp Program.

When a call is received, ground crews and equipment begin moving in simultaneously. Frequently, the “bombers” have small fires contained and medium fires under control as ground crews and equipment arrive for the mop up. Big fires may require days of joint air/ground effort. Of course, difficulties are compounded and routines altered by high winds, rugged terrain, and the fire’s proximity to structures.

Federal/state mutual aid

While the state mounts “lightweights” (helicopters with drop capacities of 100 gallons) and “middleweights” (the Grummans with drop capacities of 800 gallons), the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) brings up the “heavies.” USFS has 15 air tankers—DC-4s, PBYs, and KC-93s—each carrying at least 2,000 gallons of retardant, and a fleet of 17 helicopters based in California. All the USFS aircraft are supplied by private operators on contracts.

The California Department of Forestry’s (CDF) domain is privately-owned wildland outside corporate boundaries and organized fire districts. Its fires are fueled by grasses and chaparral in the south, woody oak brush in the midlands, and tall timber in the north.

USFS is, of course, responsible for fire control within national forests. In practice, fire suppression everywhere in California, other than in the cities, often becomes an exercise in mutual aid.

Cooperation between state and federal emergency agencies in California reaches levels of coi mon sense that may be unsurpassed elsewhere within either federal or state governments. With 13 air attack bases dispersed statewide, state and federal-service aircraft are parked together. Air-director offices for each service are neighbors at the bases. Information, problems, and advice are shared. A fire call to one agency alerts the other, When mutual aid is need, state planes fly the forested areas or federal planes patrol the wildlands in easy coordination.

USFS-CDF mutual aid extends across state lines. The Forest Service often imports additional “heavies” when backup is needed in California’s wildlands, and CDF similarly sends its planes out to national forests. California also exchanges assistance with rural fire districts and communities near political boundaries.

Size up

California plots each fire-control region into areas based on vegetation (fuel), pitch (slope) of terrain, and any special factors affecting fire control. Minimum equipment response is pre-determined, then adjusted three times daily in accordance with existing wind, temperature, and weather conditions.

The incident commander on the ground normally controls all resources for fighting the fire, but is likely to heed advice from the air attack commander circling above, who has a much better viewing platform.

Which service directs the operation during a combined state/federal fire fight? The one in whose district the fire occurs.

A fire retardant chemical, currently supplied by Monsanto, is mixed with water at fire attack bases and pumped into tanker planes at 400 gpm, allowing the Grummans to take off four minutes after engine shutdown at the pumps. Principally di-ammonium phosphate with added thickener and fast-fading orange-red dye to aid in spotting the drops, the retardant aids foliage re-growth by fertilizing.

Firefighting evolutions

When terrain permits, pilots fly their runs at an altitude of 75-125 feet for maximum accuracy and minimum drift-off of retardant. Smoke impairs visibility, of course, but it also aids in detecting wind direction. This helps determine direction of burn, drop points, flight approach and departure routes.

Tanker planes usually avoid drop routes involving steep climbs. Even though the multi-engine planes have plenty of power, there have been too many accidents to tankers trying to outclimb hills. If possible, pilots will “sling” their retardant loads from shallow dives onto fires mid-way up slopes. Air detectors suggest the flight routes, but if pilots don’t consider them safe, they can decline such runs.

Techniques for directing tankers differ. CDF directors orbit overhead, describing routes and drop points, while USFS directors in lead planes fly the actual routes, trailed by tankers like goslings after mother goose, often using a wingwaggle to signal drop points.

Although pilots try to avoid striking ground personnel and equipment with their drops, it sometimes happens. The victim may require nothing more than a good scrub on exposed skin and clothing, mostly to remove color, since the retardant isn’t caustic. However, a direct strike comes with startling power. There is potential for serious personal injury and equipment damage.

Helicopters usually drop only water, scooped into their suspended tanks from any available source. On extensive fires, bulk loads of chemical retardant are brought near the site for chopper use.

The helicopters are invaluable for dousing small key control points on fires and stubborn hot spots inside perimeters. They also serve to transport personnel and small equipment as well as setting up controlled burning for a firebreak by use of helitorches (see FIRE ENGINEERING, June 1984).

While the U.S. Forest Service can occasionally allow fires to burn themselves out on the public lands that it protects, fires on private lands often involve a threat to people, structures, or crops. Therefore, California instituted a prescribed burning program to remove older, heavier brush (mostly chaparral) from private lands. Of benefit both in fire control and in land improvement, the program was accelerated three years ago when the legislature agreed to state funding of the burning and, more importantly, paying for necessary liability insurance coverage. Since even controlled burns occasionally misfire, the uninsured hazard was more than landowners cared to face.

California consults with interested agencies (such as archeological, wildlife, water resource, and environmental) in determining areas to be burned. Costs are shared by landowners, pro-rated according to estimated benefits. Helitorches come into use here, too, for accurate and complete establishment of burn perimeters.

Of fires causing large damage in California wildlands since 1965, 20% have been set by arsonists, equipment use caused another 20%, campfires 16%, and lightning 5%.

Despite preventive police efforts and public education, California’s need for fire protection hasn’t diminished. But with its high-andlow strike forces, neither has its ability to respond.