|

| (1) The Mantoloking sign at the base of the Mantoloking Bridge. (Photos courtesy of the Mantoloking Office of Emergency Management unless otherwise noted.) |

By CHRISTOPHER NIEBLING

Late in the evening of October 28, 2012, Hurricane Sandy struck the coast of New Jersey with a ferocity the likes of which had never been seen before and, I hope, will never be seen again.

Mantoloking, founded in 1911, is situated on the Barnegat Peninsula, which separates the Barnegat Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. The borough is 2½ square miles long, is approximately three feet above sea level, and has approximately 520 residences. Several members of the Mantoloking Volunteer Fire Department (MVFD) are part of the borough’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM), which is located on the island and is also staffed by administrators and police department members.

When we first heard that a storm could approach the Northeast coast, all eyes focused on its potential path. As the days continued, most models showed this storm hitting New Jersey. The MVFD called for its volunteers to respond; it started preparing for the storm by fueling up all vehicles, gathering equipment, and preparing the station for storm damage and flooding. The media reported that several storms were converging to form a “superstorm.” In addition, a full moon and a high tide were expected as the storm was to make landfall. Our anxiety levels started to increase. The OEM was activated, and the MVFD and police met with OEM members to discuss plans for evacuating residents and personnel.

The delineation of duties and responsibilities of each OEM member must be outlined and understood well ahead of the onset of a storm or incident. Trying to determine who is responsible for what job or function within the OEM after an incident has occurred is not productive and will only cause confusion and drastically impede progress.

Forty-eight hours before the storm, reverse 911 calls were made to all residents asking them to evacuate the island. OEM, MVFD, and police personnel also walked to each residence to advise those who were at home of the evacuation. As additional information on Sandy’s intensity and the pending storm surge was received, OEM decided that all personnel would evacuate the island prior to the storm’s landfall.

Twelve hours prior to Sandy’s landfall, fire apparatus was relocated off the island and housed at a private warehouse approximately one mile west. This predetermined location was chosen because of its close proximity to the borough. Police personnel remained on the island until approximately four hours before the storm hit and then relocated to the warehouse for their safety. Residents and businesses boarded up, took their belongings, and secured as much of their property as they could. Boats were either hauled from the water or secured in their slips.

Apathy about Sandy’s intensity was evident; most residents were used to dealing with nor’easters, which are typically two- to three-day events with wind, rain, and minor to moderate flooding. Generally, towns recover quickly, clean up, make the repairs necessary, and go on with life. A dune system comprised of elevated sand approximately 12 feet high was in place prior to the storm and had always protected the barrier island. In past decades, these dunes had worked well. Not this time.

Hurricane Sandy struck the lower half of New Jersey near Atlantic City during the night. As the winds increased, all we could do was watch for incoming water. Between 10:30 p.m. and 11:00 p.m., the water came in fast. In minutes, the streets became impassable. Some residents had to make quick decisions as to whether to stay in, retreat upstairs, or simply evacuate their homes. Some stayed; some left.

|

| (2) Hurricane Sandy’s storm path. (Courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.) |

Shortly after Sandy’s passing, Mantoloking was under more than three feet of water. As I approached the Mantoloking Bridge to drive over to the island, the view of the devastation was incomprehensible; debris and boats were strewn about everywhere. After the officer at the police checkpoint waved me through, I drove to the top of the bridge and saw the image that made me stop my vehicle and just stare.

Driving was treacherous because of all the debris from homes, vegetation, and residents’ personal property. Looking north from the corner of Downer Avenue and Route 35, I saw approximately four to five feet of sand in the roadway and power poles and lines lying on the ground, and I heard the sound of natural gas blowing out of homes and the street. On arriving at the OEM, I met Detective Stacy Ferris and began working.

FIRST ASSESSMENT: WHAT ARE THE FACTS?

Our initial assessment was that all electrical power was down and natural gas was leaking from multiple homes and the streets throughout the island. Water was flowing throughout the island because of multiple water line breaks. Sewage lines, phone lines, and television cables were down. There were also three breaches from the ocean to the Barnegat Bay; the Herbert Street breach was the worst. OEM had power from an elevated generator and was running on natural gas.

OEM assessment. OEM’s gas line to the generator link was on a separate line from the rest of island; this was done in case of a catastrophic event. Unbeknownst to the OEM, several homes were on the same line. When the gas to the island was shut off, OEM and about 10 homes still had gas flowing to them, and some homes even had working pilot lights. This was not discovered until several days after the storm.

Lights, power that was running computers and radios, and portable radios, including the OEM base radio, worked. Phone lines were down, and no backup communication was available. The only other communication available was through personal cell phones. However, Sandy knocked out approximately 40 cell towers, causing weak to at times nonexistent cell signals.

Resource assessment. Because the police and fire departments and the Department of Public Works took precautions prior to the storm, a minimal number of vehicles were lost.

Operations assessment. Communication was our first priority. We had radio communications with Ocean County OEM and police units in the borough. We quickly realized that we needed phone service other than our personal cell phones. We contacted Verizon’s emergency services division (have this number on file prior to an emergency; it will save you much time and aggravation using your cell phone’s Internet capability) and requested four cell phones and two hot spots. Hot spots are imperative; if you lose Internet capability through normal means, they will give you Internet access, which becomes critical for communications and when ordering supplies or replacement equipment.

|

| (3) Herbert Street breach. |

Police officers were coordinated to respond throughout the borough, to perform a “snapshot” assessment of the island, and to check up on residents who stayed on the island during the storm. All residents were accounted for, and we quickly learned that the three breaches that cut swaths between the Atlantic Ocean and Barnegat Bay had cut the borough into thirds. At this point, the response from outside agencies was tremendous. Urban search & rescue teams came from the south to check all residences on the island.

Daily operations were set up for the borough across the bridge to the west of the private warehouse, where the borough administration and police department rented offices. Each morning, a briefing and review of the action plan were conducted in the warehouse bays for all personnel working that day. At the end of each day, personnel met at the warehouse for a debriefing and information gathering.

Security became a new concern. The island was extremely unsafe to transverse because of debris, sand, leaking gas, and water. Police officers were able to move into the borough carefully from both the north and south ends by land, but the middle area was cut off because of the newly created inlets. A local boat towing company was hired to transport police officers to the middle section of the borough to work on foot.

|

| (4) Looking north at Route 35 and Downer Avenue. |

Security of the borough’s borders was a high priority. Residents wishing to access their homes attempted to enter the borough but were turned away because of the hazards previously mentioned. Looting was the other security concern. A regular schedule was established for patrol by local police and New Jersey state troopers.

LOGISTICS

It became evident early in the recovery that we needed to make purchases and obtain authorizations/purchase orders (POs). The borough’s administrative officer was one of the first people issued a cell phone. Needing a PO number for a specific purchase or rental, we reached out and got the authorization. Standard vehicles such as patrol cars and SUVs were not useful in moving about the island because of the severe debris and sand. As a result, we rented and purchased several all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), which became invaluable for patrolling the roadways and the beach area.

Fuel was another logistics aspect that needed planning. ATVs, bulldozers, and front-end loaders all require fuel. After the storm, the majority of the state was without power. Therefore, gas stations were either closed or damaged. All the area towns and boroughs had the same concerns and needs. Fuel companies were sympathetic, but each company was already taxed to its limits.

Fortunately, a Mantoloking police sergeant had a friend in the fuel business and called him. The next day, two 500-gallon fuel tanks arrived-one for diesel and one for gas. Those tanks were still in place and being serviced by the fuel company at the time this was written. Check your internal resources; you may be surprised at what you can accomplish or obtain.

When handling logistics, you may encounter surprise requests. As our police officers continued to patrol the island, contractors working on clearing the roads found weapons buried in the sand and debris. This identified a need for storage of these weapons as well as storage for our police department’s weapons and ammunition. The police department’s storage area for its weapons was destroyed in the storm, so we ordered a metal shipping container that could be locked and a gun safe to place inside the container to secure all weapons.

POLITICS

A few days after the storm, residents wanted to get back to the island to see and secure their homes. Residents had seen the media’s aerial images of Mantoloking, but they did not know the full extent of the damage and destruction that enveloped the borough. The concern for everyone’s safety is the priority. Pressure mounted from the residents for the mayor to allow access to the island. The mayor and several council members arrived at the OEM five days after the storm intending to let residents on the island immediately.

In the State of New Jersey, when a Declaration of a State of Emergency is issued by a local jurisdiction or the Governor’s Office, ultimate authority rests with the jurisdiction’s OEM coordinator. Mantoloking OEM Coordinator Courtney Bixby, Ferris, and I sat down with the mayor and council representatives and explained the severity of the damage and our concerns. Because the elected officials had not seen for themselves the full extent of damage and safety concerns, tensions ran high. A compromise was needed.

|

| (5) All-terrain vehicles in the OEM’s parking lot. |

A neighboring town with the same political pressure had invited area civic association representatives on a private tour of its area to show the representatives the full extent of the damage and concerns. We suggested this idea to our officials, and they agreed. The next afternoon, 12 local representatives of the borough’s civic association boarded a military truck and were given a firsthand look at the island. Many returned from the tour in shock. Officials now understood why the OEM kept the island closed. When the word got out, pressure from the residents reduced.

Communication is key for information disbursement. Residents needed to know when and how they were to be granted access to the borough. Initially, the only communication the OEM had for displaced residents was through the borough’s Web site. Because the Internet was not initially available in the OEM, we contacted the borough’s Web administrator in Connecticut by cell phone. From there, information was placed onto the Web site. Workers from state and federal agencies worked around the clock to repair the breaches, and the state road that ran through the town was under construction (the side roads were almost impassable).

CREDENTIALING/CONTROL OF ACCESS

We formulated a plan to allow access to the borough to residents only. Because we had multiple agencies on the island for security including state troopers from the northeast and southeast United States as well as the National Guard, an identification system and day passes were implemented.

|

| (6) Barnegat Lane. |

In the first days after the storm, residents using the borough’s Web site could apply for a time to access the island. Each resident would receive a police escort from a checkpoint to only his or her home and was allowed up to one hour to retrieve personal belongings that could fit into a suitcase, and then the resident was escorted back to the checkpoint. As the island became more stable, colored passes were issued to each resident and specific times for accessing the homes were posted on the Web site.

LOCAL VS. COUNTY OEM

In an emergency where your local and county OEMs are activated, a protocol is typically followed when requesting equipment or services. For example, if you want to request from the field a specific size generator from your OEM, fill out the request form as established by the county and submit it. Ferris and I made countless requests for resources from the county OEM only to get no answer by e-mail or phone; at one point we were told over the phone that if we kept calling, our requests would take longer. Meanwhile, the requests from the field units and the identification of needed resources continued. Several days into the recovery, Ferris and I attended a meeting at Seaside Park with area police chiefs, state troopers, and New Jersey’s attorney general. In that meeting, all voiced the same concern about the lack of cooperation and response from the county OEM; we were all told that if we needed resources, we had to order them ourselves.

This is a prime example of a breakdown within the system. As with most local and county OEM systems, a request was made from the local OEM following standard procedure. The request is received and acted on, and an answer comes back to the local OEM within a reasonable time frame. This did not happen here. The system failed, and we were left to secure our own resources. All of the tabletop practices and exercises you have trained on and prepared with cannot prepare you for when the system breaks down.

FEMA/DATA CAPTURE

|

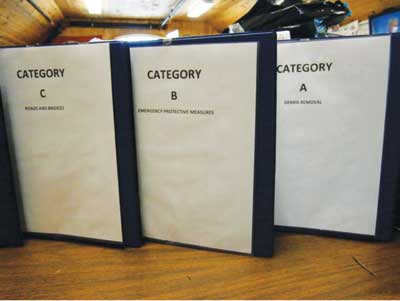

| (7) FEMA’s category books. |

Always document your procedures. Early on in Sandy’s aftermath, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) started to become a presence. Nearly every day, a new FEMA representative visited the OEM. We knew from experience that documenting and capturing information were critical for insurance and to FEMA. What we didn’t know, but soon learned, was how critical these practices were and how you obtain and categorize these data. If you plan or expect to be reimbursed by FEMA for expenses incurred from and during an incident, you MUST have a system in place to collect this data.

As Mantoloking’s responders, we have met with engineers and contractor representatives that handle debris (both household and building), sand (including depth and replenishment), utilities, waterways (including debris), general building issues, and roads (including height and depth). One of the repetitive problems encountered with FEMA was the sheer number of representatives who attended meetings at the OEM and the change of personnel/representatives. Many times, we met these representatives and explained our concerns and needs. The individuals would take notes, tour the island, and ensure us of what we could accomplish. After a week or two, a new set of FEMA representatives arrived at the OEM to tell us that the previous representative had been transferred or that they were now handling this matter, forcing us to repeat all that was explained/shown to the previous representative.

The capturing of all this information can be overwhelming; you MUST run your OEM smoothly and efficiently and have it staffed accordingly. Currently, five of us operate as a team; Ferris is the only full-time member. Cooperation from all departments within your town, borough, or city is the key. Everyone is under additional stress because of the storm; bring critical incident stress debriefing representatives in early to help with this additional stress. As of this writing, I will be shifting from Operations/Logistics to data entry for the borough’s FEMA reimbursement. This will be a long process but a necessary one and a learning experience.

● CHRISTOPHER NIEBLING is a 36-year fire service veteran who served as a fire officer, fire instructor, and paramedic. He has lectured at FDIC and state conferences. He is a member of the Mantoloking (NJ) Volunteer Fire Department and a deputy for the Office of Emergency Management for Mantoloking. He has been published in Fire Engineering, was the senior editor for the text Pump Operator-Principles and Practice, and is a technical advisor for the Fundamentals of Fire Fighter Skills DVD series. Niebling is the former chairperson of the Florida Training Improvement Conference, a state conference for fire service instructors, and vice president of the Florida Chapter of the International Society of Fire Service Instructors.

MANTOLOKING

Fire Engineering Archives