HANDLING MULTIFATALITY INCIDENTS

Think back to the last disaster/mass-casualty drill your organization held. If it was typical of the hundreds of such drills held annually throughout the country, it involved a scenario dealing with an aircraft crash or exposure to a hazardous material; many different local agencies or groups that potentially may be involved in such an emergency participated; and many victims who were triaged, treated, and transported to local hospitals. Once the last victim reached the medical facility, the incident commander ended the drill and gathered all participants for a critique. This scenario is repeated hundreds of times a year all over the country and. as has been evidenced by some recent disasters, with a great deal of success.

But wait! Is the drill really over at the point at which the last ambulance arrives at the hospital? What about the “victims” who didn’t survive—the “gray tags” that the often “superhuman” firefighters and paramedics were unable to save? “No problem,” you say. “That’s the coroner’s job. Our job is saving the living. We’re outta here.”

You are correct about saving the living, but a major part of a disaster still must be managed after the last victim has arrived at the hospital. You must be prepared to handle a mass-fatalities incident of the magnitude that could result in hundreds of casualties.

In such mass-fatalities incidents, recovering, removing, identifying, and disposing of the remains of the victims are next in priority to saving the living and mitigating hazards. In addition to being a part of our culture, properly caring for the dead often is critical in determining the cause of an incident other than a natural disaster. Improperly handling the dead during an incident can hinder the process of properly identifying the dead and can remove from the scene important clues relative to the cause of the disaster. In an incident involving fatalities, it is critical that the incident commander begin the planning process for recovering and identifying the dead early in the incident response phase.

Since a number of public and private agencies and organizations may become involved in this phase of an incident, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). the National Funeral Directors Association (NFDA). and other organizations have begun a massive effort to organize and standardize the fatality phase of a mass-disaster incident. The NFDA has been instrumental in forming disaster mortuary response teams (D-MORT), similar in organization to the disaster medical assistance teams (DMAT) under the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS). The NFDA also has invested thousands of dollars and many hours of time in organizing regional and state disaster response teams (see page 40).

In addition, FEMA, through the Emergency Management Institute, in conjunction with other groups such as the NFDA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, redesigned the three-day Mass Fatalities Incident Response course, which covers components such as incident-management techniques, teamwork among many agencies, and worker reaction to death.

MASS-FATALITIES INCIDENT DEFINED

Any incident that overwhelms local resources is considered a mass-fatalities incident. We normally associate these incidents with transportation accidents or other “man-made” events such as explosions and fires. However, natural disasters can cause as many or more deaths throughout a wider area than these events. In some areas of the country, three or four fatalities can overwhelm local resources. In large urban areas or big cities, the local medical examiner’s office may be able to handle 50 or 60 fatalities without disrupting the normal daily workload. The key point is that normal dayto-day operations in the medical examiner’s office must be able to continue during the disaster in much the same way as they would in public safety organizations.

INCIDENT COMMAND AND THE MASSFATALITIES INCIDENT

Recent natural and man-made disasters have proven our effectiveness in mitigating hazards and saving lives. Part of the reason we have become so proficient in these functions is that we have restructured our organizational skills, most notably by implementing the incident command system. Freelancing at the incident scene no longer is accepted or tolerated, and many diverse public safety agencies now work together to successfully manage disasters.

The question of who is in charge of the fatality phase of the incident always arises. By law, the local medical examiner or coroner is responsible for identifying and releasing the bodies. However, most local medical examiners or coroners do not have the staff or expertise to manage all aspects of such an incident, such as logistics, transportation, and communications.

Since an intricate command and control structure is already in place to manage the response phase of the incident, why should it not be used to manage the mass-fatalities portion of the incident as well, especially since many of the same agencies instrumental in the response phase will continue to play a part in the mass-fatalities phase? Although the incident commander may change, the command structure should be retained after the response phase of the incident has been concluded and expanded and be adapted to accommodate the mass-fatalities function. The most notable difference between the response and mass-fatalities operations are (1) the pace will change a little and (2) some different branches, groups, and individuals will be added. In addition, individuals with whom we may not be accustomed to working within our normal response phase mode—such as funeral directors, medical examiners, fingerprint specialists, and forensic dentists—-will be added.

PHASES OF MASS-FATALITIES INCIDENTS

The four main areas to consider when preparing to implement operations at a mass-fatalities incident are the following: recovery of bodies, removal of bodies, identification of bodies, and final disposition of bodies (these phases are described below). The incident commander (the Planning and Logistics sections), as already stated, begins planning for this phase at the beginning of the incident. It is too late to begin thinking about what to do with the dead bodies after the last victim leaves the scene and the area is stabilized. It is highly probable that a local lire, emergency medical, or other local government official will function as one of these section chiefs.

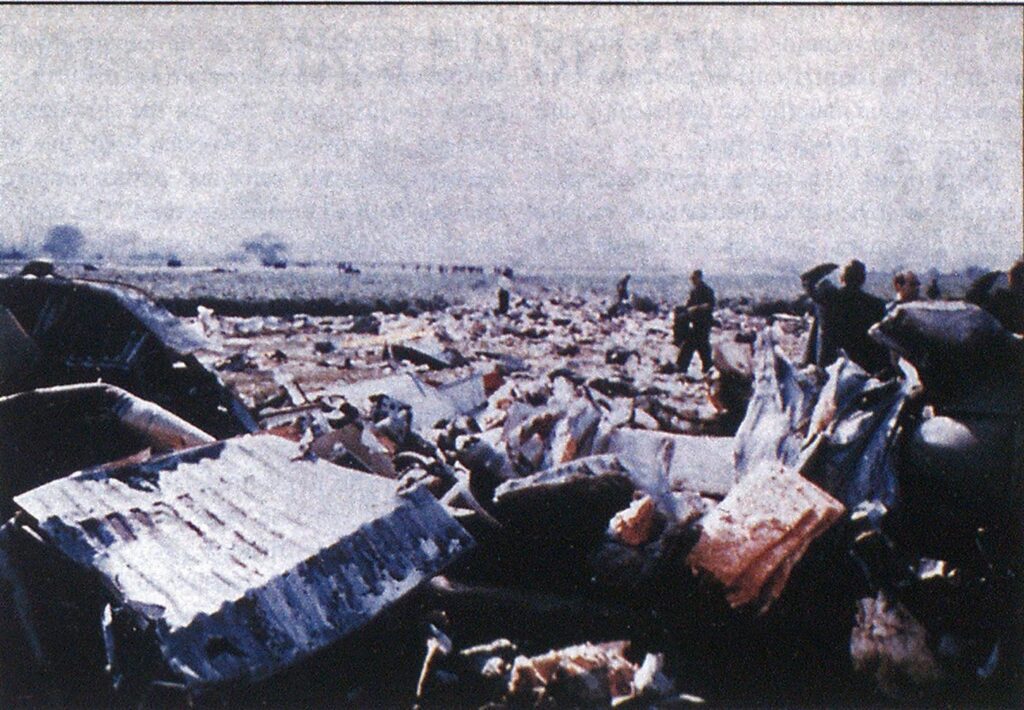

• Recovery: This phase covers the process of locating bodies, body parts, and personal effects at the disaster site and documenting on paper and film the location of each body and body part and personal effects. In some cases, the disaster site is gridded to facilitate locating and identifying the bodies, as well as to determine the cause of the disaster. It is extremely important to make a comprehensive videotape of the site before and after human remains and personal effects are marked. The tape can assist in locating the exact placement of the items on the scene if such information should be needed at a later time.

(Photos courtesy of the Emergency Management Institute’s Mass Fatalities Incident Management Course.)

Emergency responders assigned to help with this phase often experience some confusion. Some feel that all bodies and parts should be covered as soon as possible and that personal effects should be removed from the scene and turned over to law enforcement personnel. Covering bodies and removing personal effects should be avoided. The locations of personal effects at the disaster site can be very helpful in identifying bodies. A body covered with a white sheet may not be removed from the site for many hours and probably will be removed by someone other than the individual who covered it. It becomes almost impossible to distinguish between sheets that become bloodstained and soiled through exposure to the disaster and those placed there afterward. Covering bodies also hinders the photographing, videotaping, and gridding processes used to document the disaster site: the remains and personal effects will not be readily visible in the video or photos. Concern about the news media’s photographing dead and mangled bodies should be resolved by moving the media to a safer location away from the bodies.

Leave all remains and personal effects as found unless they are hindering the rescue of a live victim or hampering other emergency operations. Don’t be in a hurry to gather personal effects for security reasons or remove the bodies from the disaster site. Leaving the scene intact can aid in the body-identification process and provides clues to the causes of man-made disasters. It is best to treat the disaster site as a crime scene until it has been proven otherwise.

Ideally, search and recovery teams consisting of three to five members would report to a search and recovery team leader. The number of teams would depend on the number of bodies, the size of the disaster site, and the time frame allotted for recovering the bodies. The operations officer would coordinate these functions. Each team should consist of a scribe, a photographer, and at least one person to flag, tag, or otherwise label bodies, body parts, and personal effects on the scene. Since most medical examiners or coroners have a limited staff, it is very likely that fire, EMS, and law enforcement personnel will assist with this part of the operation. Funeral directors trained in disaster operations also should be members of the search and recovery’ teams.

Mark all remains and personal effects with a predetermined numbering system using a stake or (tag. The numbers should stay with the remains as they are moved through the identification process. Use weatherproofed material for the labeling and spray paint for paved surfaces.

• Removal: Once the scene has been carefully searched and documented and the bodies, body parts, and personal effects have been labeled, they must be systematically removed from the scene. They must be carefully packed and taken to a temporary morgue, the regular morgue, or a designated holding area from which they will be removed to the morgue.

Place bodies and body parts in separate body bags that have been carefully marked on the inside and outside. Use opaque body bags with a full zipper around the edge to ease moving the remains once they arrive at the morgue. If not attached to the remains and identified with regard to their specific locations in relation to the nearest remains, place personal effects in separate plastic bags.

When the bodies are ready to leave the scene, a disposition officer should carefully document the body number, vehicle, and personnel driving the vehicle. When possible, unmarked professional funeral home vehicles or, in the case of a large number of remains, an unmarked closed truck should transport the bodies.

• Identification: Determine early in the response phase whether the regular morgue can accommodate the bodies or a temporary morgue must be established close to the disaster site from which the bodies can be transported to the regular morgue as space becomes available.

If a temporary morgue is used, the Planning and Logistics functions should identify early in the incident a suitable site for a temporary morgue and assemble the personnel and equipment to operate it. The morgue site must be close enough to the disaster site to facilitate access and yet be far enough away so that ongoing operations are not disturbed. Other considerations are that the temporary morgue site not have a wooden floor, that it have an adequate water and power supply, and that it can be easily secured. The community’s mass-fatalities disaster plan should identify predetermined sites that quickly can be used if needed. Make all contractual arrangements in advance to avoid delays at the time of the incident.

A body holding area used in a mass-fatalities incident. Because the bodies were left on the floor, Body ID Team members quickly tired from having to work bent over.

A more suitable arrangement using makeshift plywood tables to hold the bodies in the initial processing phase.

All body identification operations will be conducted at the morgue site under the direct control of the local medical examiner or coroner and function under the operations chief. Visual identification alone is not reliable and is not legally defensible. All bodies and body parts, therefore, must be processed in the same manner. Establish the following processing stations in the morgue:

- body reception, including photographing the body and cataloging personal effects;

- body X ray;

- fingerprinting;

- dental examination; and

- autopsy.

In a very large disaster with many bodies, embalming may be done at the temporary morgue. However, it is desirable that this procedure be done at local funeral homes, whenever possible.

The National Foundation for Mortuary Care, a nonprofit organization formed to support mass-fatalities operations, maintains a completely stocked portable morgue and a large cache of disaster supplies at the Sky Harbor International Airport in Phoenix, Arizona. This equipment is available for use in a disaster and must be requested by the proper authorities. Many state and regional teams also maintain well-stocked disaster trailers.

TECHNICAL SPECIALISTS

During the identification process, the medical examiner calls in various technical specialists (sometimes from outside the area) to properly identify the remains. In some types of disasters, burns, mutilation, or other causes make it difficult to identify the bodies. In these cases, forensic dentists may have to compare dental records or even individual teeth found at the disaster site to make a positive identification. Forensic anthropologists can determine the size and gender of victims from bones randomly found on the site.

The FBI disaster squad is ready to respond within hours to destinations within the United States to assist in the identification of victims through fingerprints. Any local law enforcement agency can request this free service.

FAMILY ASSISTANCE

Caring for the families of the disaster victims is an integral part of the identification process. The logistics are much easier when the disaster involves victims from the local area than when victims’ families must be brought in from out of town. Whichever the case, mobilize a family assistance center to address the concerns of the victims’ families early in the response phase. This center site, which generally is a fire station, school building, or hotel, should be remote from the disaster site and temporary morgue. Members of the identification team will be interviewing family members to assist in identifying the bodies. Once family members have made a positive identification, they must be assisted with final disposition plans, especially if the victims are from out of town or the incident involves a common carrier. Most underwriters have very strict requirements involving the care and disposition of human remains in a disaster.

The Family Assistance Center staff would include the medical examiner’s staff, mental health professionals, Red Cross volunteers, clergy, and funeral directors. An EMS presence is recommended to care for family members who may become ill or react to the stress of the situation.

DISPOSITION

In a local disaster in which the victims are from the area, the disposition phase is fairly simple. The medical examiner releases the bodies to the local funeral directors for final disposition according to the wishes of the family. The process becomes much more complicated if the disaster involves people outside the area, people from other countries, or a common carrier.

Although the medical examiner is still responsible for releasing the bodies, out-oftown shipments must be coordinated with local funeral directors. Bodies that will cross state lines or that are to be shipped by common carrier must be embalmed. If the disaster involves people from other countries, those consulates will be involved. This can become a logistical nightmare; and again, the incident commander must begin to plan for the possibility of such a scenario during the early stage of the incident. If not managed properly, this phase easily can become a media circus, which will reflect negatively on local officials, who may not even be directly involved in the process.

LOGISTICS

As you can see from our discussion of the four phases of a mass-fatalities incident, many people and physical resources are needed within a short period of time. If not prepared, the Planning and Logistics sections easily can be overwhelmed by the magnitude of the operation. The incident commander must carefully choose the individuals to head these functions early in the incident. They must be thoroughly familiar with the community’s disaster plan and knowledgeable about the multiple aspects/ requirements of this type of incident.

The disaster plan should include comprehensive resource and equipment lists that are readily accessible to the command staff. The logistics chief should not have to negotiate contracts and haggle about who’s paying for supplies during the incident; all this should be predetermined and be part of the plan.

DEATH AND THE EMERGENCY RESPONDER

The emergency responder is geared to rapidly intervene in the dying process to save a human life. Often, that is not possible during a multiple-fatalities incident; death often occurs before or after the responder’s arrival. In disasters involving many fatalities, emergency responders may have to act in various roles during the fatality phase. Leaders must be aware that not all personnel are capable of serving in these roles. Even the most aggressive firefighters may be seriously affected by the horrors and finality of the situation. Some individuals may not be suited for this type of work at all and may find it difficult to accept the realities of death. These individuals should be assigned duties away from the disaster site. The incident commander must carefully monitor emergency responders working at the disaster site and provide them with adequate and regular relief away from the site and, early in the incident, should arrange for the services of critical incident stress debriefing teams and mental health professionals to service emergency workers and victims’ families.

PLANNING

A mass-fatalities incident is a major burden for the emergency response forces of any community. As noted, the incident commander—no matter how efficient or experienced—quickly can be overwhelmed by the extraordinary requirements of such a massive mobilization of people and resources. It, therefore, is critical that the community have a comprehensive response plan that includes a mass-fatalities component. The many diverse groups whose teamwork is essential to successfully managing an incident of this type (funeral directors, medical examiners. Red Cross, mental health professionals, law enforcement, fire, and EMS) must be brought together during the planning process so they can become acquainted with each other’s expertise.

Just as the fire and emergency medical services have become highly proficient in saving life and property in situations of all types and sizes and in organizing their forces through the incident command system, they must extend this proficiency to the massfatalities incident. Remember this the next time you have a mass-casualties or disaster drill: The drill is only half over when the last ambulance arrives at the hospital and all the fires have been extinguished.