COLD STORAGE WAREHOUSE TURNS UP THE HEAT

FIRE REPORT

Photos by Salem Leaman.

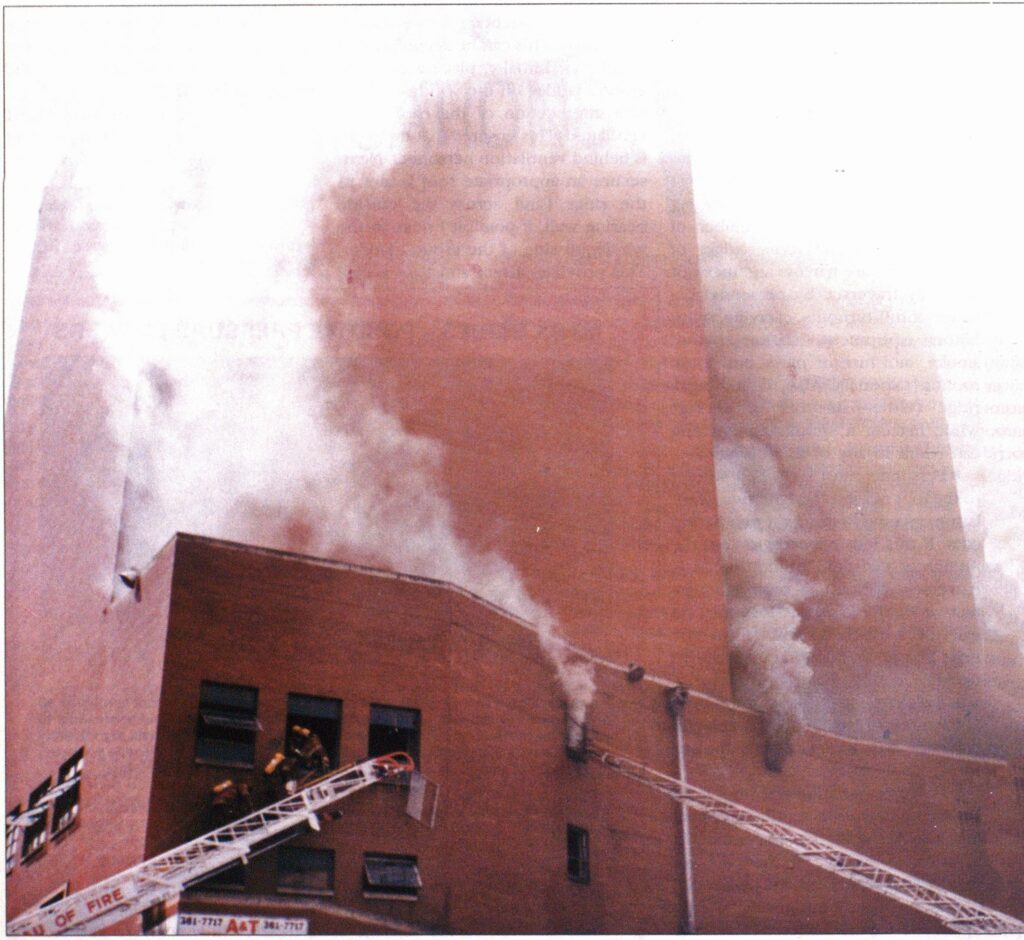

Inaccessibility, ventilation difficulties, and improperly stored paper products turn cold storage into beat and smoke storage in a Pittsburgh warehouse.

SALEM LEAMAN, a respected fire buff in the Pittsburgh area, contributed the photos for this article.

On Monday, August 21, 1989, members of the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire were called on to battle a difficult fire that tested their Incident Command System and required implementation of some unusual strategies. Ultimately, it took almost 100 firefighters manning 24 pieces of apparatus six hours to subdue the blaze in a former cold storage warehouse that was being used to store bulk paper products.

The sky was clear and winds were light. The temperature at noon was 80 degrees and the humidity was fairly high. At 1150 hours, Fire Dispatch broadcast an alarm for a reported fire on the second floor of the Allegheny Warehouse at 21st and Mary streets on the city’s south side. Initial response consisted of three engine companies, two truck companies, a squad company, and Battalion 4 Chief John Schemm. (The Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire staffs five squad units with four members each; these companies perform in much the same capacity as rescue companies. Squads are dispatched on any structural fire alarm and arc utilized by the incident commander in whatever way he sees fit.)

THE STRUCTURE

The fire structure was a 10-story brick building that formerly housed the Duquesne Brewery. The fire originated in and was confined to a threestory wing on the sector 2 side of the building. The area of each floor of this wing is approximately 6,000 square feet. Although it was used recently for general warehouse storage —the space was loaded with palletized paper products (mostly copier paper) — it was the wing’s original construction as a cold storage warehouse that posed the unique challenge for fire department personnel.

This virtually windowless section of the building has six-inch-thick concrete floors, a solid concrete interior wall lined with cork insulation, and an eight-inch-thick concrete roof, all steel-reinforced. The storage areas on the second and third floors (4,500 square feet each) are divided horizontally by heavy, open steel grating, with no vertical separation of any kind and only two small, heavy, metal-clad entry doors on each floor.

Before its occupation just a few months before the fire, the building had been vacant for years. The paper was stored without vertical firestopping and without a permit, and there was neither an automated sprinkler system nor a standpipe system. In March 1989, the Pittsburgh Fire Bureau had expanded its fire code inspection program but at the time of the fire had not reached some industrial structures on the city’s south side —among them the fire building. In the time since, however, it has increased its coverage considerably to include many such structures that operate contrary to the city fire code.

ARRIVAL

Arriving on the scene within one minute after the alarm, the first-due squad reported smoke showing on the second tloor and notified engines to take hydrants. Upon arrival Battalion Chief Schemm established a command post at the corner of sectors 2 and 3, reported heavy smoke from the second and third floors, and proceeded to direct the laying of attack lines up the only two stairways in that part of the building. According to reports from occupants of the wing, all employees had exited the building safely and had been accounted for prior to the arrival of fire units.

At 1212 hours, Chief Schemm requested a second alarm, which, in addition to bringing two engines, a squad company, and Deputy Chief John Gourley, called for response of an air supply truck carrying 40 air cylinders. Unfortunately, the fire bureau’s mobile air compressor was out of service and a shuttle had to be set up for a squad company and a supply truck to transport air bottles to and from a stationary compressor in a fire station approximately three miles from the scene. Chief Schemm ordered second-alarm units to stretch additional attack lines from the firstalarm engines, which had laid fiveinch supply lines.

Smoke in the stairwells was exceptionally thick and progress was very’ slow. However, the primary search confirmed a very heavy body of fire in the center of the storage area on the second/third floor.

ATTEMPTS TO VENTILATE

Assuming command upon arrival, Chief Gourley special-called an additional ladder truck, which upon arrival was ordered to raise its aerial to the third-floor roof and open holes in the roof to provide vertical ventilation and a means of access to the seat of the fire. Neither of the two first-alarm ladder companies had yet been able to locate any possibilities for horizontal ventilation. Engine companies were operating in zero-visibility smoke conditions and were having difficulty getting water on the fire.

Command requested a third alarm at 1233 hours, two engines and a squad responding. A staging area was established and command ordered that apparatus be left in staging and that only personnel with SCBA report for assignments as reliefs.

Because only a little smoke was venting to the outside, positive-pressure fans were placed in the two stairwells. However, because of the inability to open vent holes in the thick concrete roof, the fans were ineffective. Chief Gourley again reported heavy smoke on the second and third floors and announced that this would be an extended operation.

At 1235 hours I reported to the command post and assumed command. Also reporting were Deputy Chief Robert Kolenda, two training division captains, a fire/police arson team, and the fuel truck, along with the Salvation Army disaster service canteen. I ordered the response of Battalion Chiefs Joseph Wasielewski and Joseph Kimak. These officers, in addition to those already on the scene, were used to expand the already established incident command structure. Operations sector commander, staging sector commander, second-floor operations chief, ventilation operations chief, sector 2 (outside) operations chief, and safety officer were all in place.

A BREATH OF FRESH AIR

By this time, Sector 2 had become the scene of two vital activities: air cylinder replacement and rest and rehabilitation. Several firefighters were assigned to replace air cylinders while the Salvation Army canteen crew distributed cold drinks to firefighters who were constantly rotated in and out of the fire building. These actions were necessitated by the highi heat and continued heavy smoke still being produced by the fire. An additional squad company was ordered to assist in roof ventilation.

At 1300 hours, command requested the fourth alarm with an additional ladder truck. These companies also were ordered to leave their apparatus and spare air cylinders in staging and report to command with their SCBA ready. Relief of the engine companies try ing to gain access to the fire and of the truck and squad companies attempting to ventilate had now become the major priority.

The fifth alarm was transmitted at 1321 hours. Although the main body of fire was apparently contained in the open storage area on the second/third floor, access to it seemed virtually impossible. The ventilation group reported that it had opened several shafts on the roof but that no smoke was coming out. Smoke continued to pour only from the few small windows and vents on the sector 2 side.

At 1349 hours, after further reports of an extremely thick concrete roof and a continued lack of progress by the vent group, command transmitted an urgent request that dispatch contact the Public Works Department and request two crews with compressors, 90-pound jackhammers, and at least 200 feet of air hose. Command described this need as critical.

When crews from Public Works arrived on the scene, the jackhammers were hoisted to the roof of the cold storage wing and operated by members of the squad. As soon as the eight inches of concrete under the roofing material were breached, large quantities of heavy, black smoke poured out. Three holes were cut in the roof using the jackhammers.

Also at this time, the operations officer ordered that a portable deck gun be set up on the second floor, discharging through one of the two small man-doors into the now fully involved storage area. This deck gun was supplied by a five-inch line, stretched up an interior stairwell by fifth-alarm crews.

SWITCH TO OUTSIDE STRATEGY

Operation’s intention was to duplicate this tactic on the third floor. However, in spite of the vertical ventilation provided by the jackhammered holes, access to the seat of the fire remained difficult because of the density of the stored products and the few access points. The fire continued to gain in intensity and, after a meeting at the command post of all chiefs on the scene, we decided to shift to an outside firefighting strategy.

All personnel were ordered out of the building. The portable deck gun, however, was left in operation, unmanned, on the second floor. Outside, two ladder pipes and a deck gun were set up and used to flow water through the jackhammered openings in the roof. The object was for the water to reach the fire through the open-grate floors in the storage area and reduce the high heat and dense smoke.

At 1444 hours, with the outside attack still in progress but in anticipation of a renewed interior attack, a special alarm was ordered. This response consisted of three engines, a truck, and a battalion chief. When the outside attack began to produce the desired results, these companies advanced handlincs into the cork-insulated rooms, separating and extinguishing piles of burning material. ‘ITiis action continued until the fire was brought under control at 1748 hours—six hours and six alarms after the first alarm was broadcast.

PROBLEMS AND LESSONS

Based on an investigation conducted by the members of the Pittsburgh Arson Strike Team both before and after this fire was declared under control, the cause was deemed accidental. Specifically, improper use of electrical extension cords for lighting in the storage area was ruled responsible. These extension cords had been strung on and under plywood panels placed on the open-grate floors as walkways between stacks of storage.

Obviously, in a fire of this magnitude and complexity many problems were encountered and many lessons were learned. Briefly, the major problems were

- the high heat and smoke conditions and lack of visibility due to the inability to ventilate the roof in a timely manner because of the thick concrete construction;

- the large volume of combustible material tightly stored in a limitedaccess area without sprinklers or standpipe connections;

- the maze-like fire floor layout;

- the need for rapid and continuous replenishing of fresh air cylinders; and

- the fatigue and exhaustion of firefighters due to extended operations under extreme conditions.

- Lessons learned during this firefighting challenge were as follows:

- In addition to the apparatus staging area two blocks from the fireground, a tool and small-equipment staging area should have been established much closer to the fire building to stage blowers, portable lights and cords, portable deck guns, heavy rescue equipment, generators, and various hand tools.

- The rehabilitation area should be separate from but fairly close to the equipment staging area. This area also should encompass the air cylinder exchange and refill activities. In this way a company that is sent to rehab can, at the same time, obtain the tools and equipment needed for its afterrehab assignment as well as replenish its air supply.

- Each staging area and the rehab area must have a separate individual assigned to maintain a list of equipment and manpower available at all times. Particularly in the rehab area, the individual in charge must keep track of whether or not companies are complete or split up and also be sure that adequate time is spent in rehab. This calls for recording all in and out times.

Finally, equally important as lessons learned are lessons (concepts, strategies, and tactics) reinforced. Several emerged during this incident:

- Through the use of effective early search techniques and an effective accountability system, the incident commander can be relieved of the need to be concerned about the civilian life safety hazard and instead can concentrate on the needs of the firefighters.

- City agencies other than EMS and police can provide resources not commonly thought of as firefighting related. Creative use of and rapid, cooperative response by these agencies (public works, water works, and so on) can give the incident commander a distinct advantage.

- The Incident Command System does work and works well. As the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire faced the challenge described in this article, proper use of the ICS enabled all forces to more easily, effectively, and successfully meet and take control of that challenge.

- New equipment, apparatus, protective clothing, and a command system are all well and good; however, what can’t be purchased or commanded is the firefighter’s will to succeed. Pittsburgh firefighters rose to the challenge by doing an exceptional job at this incident