Testing High-Rise SOPs

FEATURES

TRAINING

High-rise buildings were not designed with the reach of the fire apparatus in mind. Therefore, reliance on the building’s fire protection systems and interior emergency operations are of primary importance.

Looming in the skyline of most cities, and normally requiring little attention from fire forces, high-rise buildings have the potential to tax fire department resources beyond their limits.

Realizing that its standard operating procedure (SOP) had not kept pace with the changing technology of high-rise building systems, or with a changing school of thought on fire operations in these structures, the Charlotte, NC, Fire Department revised its high-rise procedure. While each city has its own unique problems and methods of operation, Charlotte’s approach to evaluating and upgrading its ability to deal with a high-rise fire can be applied by any fire department.

A committee was appointed to examine the problems associated with high-rise fires. To ensure that the SOP would cope with most problems likely to be encountered, the committee was made up of a range of the department’s ranks and divisions: a battalion chief, three captains, two firefighters, a fire alarm dispatcher supervisor, a plans review officer, and a fire education specialist. With these diverse perspectives, work got under way, and an examination of other cities’ high-rise procedures and a review of case histories of high-rise fires were carried out.

Each committee member made a presentation in their respective field as it related to high-rise fires: Captain Doug Cook, the committee chairman, presented an interpretation of the department’s incident command system (ICS) as it would apply to high-rise operations. The other captains and firefighters on the committee had experience using an experimental high-rise pack (see sidebar) which the department was testing in the downtown area. The fire alarm supervisor presented information regarding communication capabilites and outside resources available during emergencies. The plan’s review officer had experience with fire and building codes and highrise building design, while occupant training and drills were in the field of the fire education specialist.

Months of consultation among committee members followed. Because smoke is a major problem in high-rise fires, the committee sought to establish a procedure for smoke removal. Heat, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) engineers were called in to provide information about smoke behavior and its control. What was discovered is that variables such as:

- building design

- HVAC features

- weather conditions

- fire extent

must all be taken into account when developing a smoke control procedure. A strong emphasis on pre-fire planning is important.

Elevator engineers were also contacted to provide information on elevator performance under fire conditions. More specific procedures were developed for the control of elevators, but again, the variety of elevators found in buildings pointed to the need for familiarization through pre-fire planning.

As information was obtained and discussions were held, an SOP for high-rise fires took shape. Following are some main features of the department’s SOP:

Photo by Bradley Anderson

Photos by Bradley Anderson

- For firefighting purposes, a highrise building is defined as any structure over 60 feet in height; any structure that is inaccessible to aerial equipment from one or more sides; and health care facilities having three or more floors.

- Each high-rise building must be pre-fire planned to ensure knowledge of conditions that may influence fire operations.

- First alarm for high-rise buildings includes a minimum of a battalion chief, four engine companies, two ladder companies, and a squad (a total of 30 firefighters).

- A second alarm, mandatory upon a confirmed fire condition, roughly doubles the first alarm complement with the addition of special equipment and personnel:

- four engine companies

- two ladder companies

- a team rescue company

- a hose tender

- a battalion chief

- a division chief

- the assistant chief of operations

- training officers

- a fire investigator

- the plans review officer

- Following the incident command procedure, the first-arriving officer establishes a command post in the lobby or passes command to the next arriving company. Command may be passed, via radio, in situations where the officer of the first company finds it’s necessary to accompany his crew to the fire floor before other companies arrive.

- In designing the high-rise procedure, the ICS helped sort out many of the functions necessary to control a highrise incident. The high-rise committee found that the department must be compatible with ICS.

- A telephone communications line from the lobby of the fire building to the fire alarm center should be established because radio frequencies may be overloaded and portable radios may not perform well.

- Elevators will be recalled to the ground floor automatically or manually by fire department control.

- Elevators must not be taken closer than two floors below the suspected fire floor, and then only with extreme caution, checking the function of the elevator car and the condition of the elevator shaft before leaving the ground floor. On the way up, the controls should be tested by stopping the elevator at lower floors to ensure that it is under the fire company’s control.

- The incident commander will remain in close contact with the building staff for information regarding technical features of the building and the status of smoke detection and sprinkler systems. Assistance using in-house communications may also be necessary. The plans review officer, being familiar with building design and fire operations, will coordinate firefighting efforts with building management services.

- Security and maintenance personnel should be asked to provide information regarding the progress of evacuation on the affected floors. Minimum evacuation will involve the fire floor and two floors above and below the fire floor, with subsequent evacuation of additional floors if conditions warrant. Handheld carbon monoxide monitors are being purchased to check areas where occupants have not been evacuated.

- All personnel going above the ground floor will be equipped with self-contained breathing apparatus.

- The incident commander should establish sector control of the fireground, appointing officers to take on responsibility for each of the necessary major functions. These functions might include, but are not limited to, rescue and evacuation, water supply, communications, salvage, fire attack, ventilation, staging below the fire floor and company staging into the fire scene.

A third alarm includes another battalion chief, a ladder company, and three engines. Subsequent alarms bring three engine companies each.

Not long after the new SOP was adopted, an alarm was received for a fire at the Southern National Center, a 22-story office building. Upon arrival, the first-due company officer was met by his battalion chief and informed that this alarm was a training exercise. The officer was to act on reports from security personnel of a working fire on the 16th floor.

continued on page 60

continued from page 58

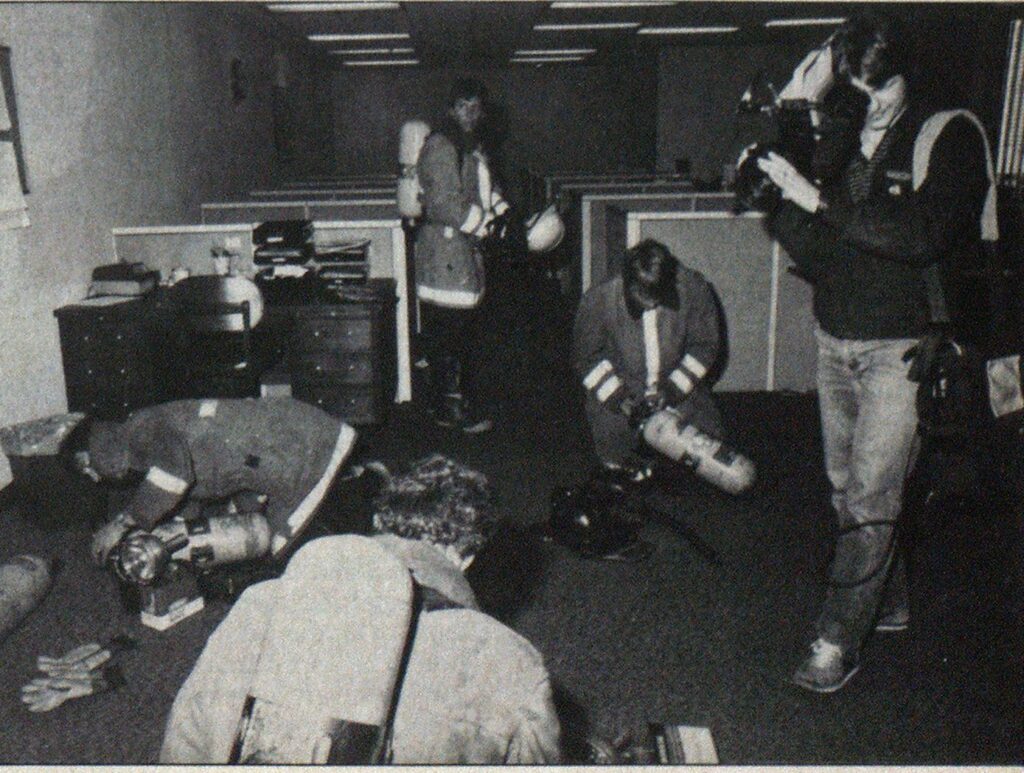

This exercise, held on a Sunday morning to minimize inconvenience for occupants, put firefighters through the paces under the watchful eyes of fire department observers, including high-rise committee members placed strategically throughout the building. In the following two hours, firefighters searched floors 14 through 22, rescuing 30 “victims” (explorer scouts with simulated injuries) and removed them to a triage area on the building’s loading dock for ambulance personnel to evaluate and prepare for transportation.

High-rise pack

High-rise packs, carried by all engines assigned on a first alarm for high-rise structures consist of:

- 200 feet of 2-inch hose

- medium flow nozzle (125 gpm to 200 gpm)

- hydrant wrench

- pipe wrench and spanners

- 10 foot section of 2 1/2-inch hose for recessed standpipe connections

- 2to 1 1/2-inch reducer

- 150 feet of 3/4-inch nylon rope for hoisting

- axe

- sledgehammer

- bolt cutters

- halligan tool

- 24 rubber lock stops (sections of inner tube for holding open door latches and for marking areas that have been searched).

This equipment is carried in a container on a wheeled dolly.

With supervision from the heavy rescue team and an elevator mechanic, firefighters rescued victims trapped in an elevator. Two-inch attack lines from high-rise kits were stretched from standpipes on the floor below the fire (but were not charged to avoid damage). While these and other operations took place, observers on each floor made notes and kept track of the times of different operations.

A public information post was established outside the Southern National Center. News media representatives were escorted through the building during the exercise and permitted into “involved” areas. This resulted in news stories that educated civilians about the problems and dangers of high-rise fires.

Critique

Finally, the incident was declared under control, and everyone involved in the drill, including firefighters, building management, ambulance personnel, and victims, reported to a conference room to critique the exercise.

The critique identified the strengths and weaknesses of fire operations, building features, and the high-rise SOP. One weakness, which occurred early in the operation, involved the first-arriving engine company. Unsure about the use of elevators with a confirmed fire condition, this company proceeded with SCBA and a high-rise kit to the 16th floor via a stair tower. Twenty minutes later an exhausted crew arrived at the fire floor. Other companies had used elevators under the fire service control feature to move personnel and equipment to the 14th floor staging area. However, at least the error was made in favor of safety. Another problem discussed was communication difficulty. This stemmed from a reduced effective range of the walkie-talkies in a steel structure and the problem personnel had in identifying exact locations within the building. The procedure of opening a telephone line to the communications center from the command post to relay radio messages proved effective in overcoming the communication problem. The need for frequent review of high-rise buildings and their pre-fire plans by first-alarm companies was reinforced by the location problem.

photo by Bradley Anderson

With only a first alarm assignment involved, the operation went slowly. The systematic search of floors while firefighting operations were being simulated took 1 1/2 hours and was not completed on all the floors. Observers declared some victims deceased before they could be moved to the triage area. It was determined that triage should be established on a safe floor, closer to the involved floors of the building. This would ensure quicker triage, treatment, stabilization, life support and transportation of victims.

The exercise was considered a valuable learning experience and was well received by firefighters, despite its surprise. It also provided an opportunity to objectively review the new high-rise procedure with a degree of hindsight.

In preparing the high-rise procedure, three factors were identified that could have significant bearing on the outcome of a high-rise fire:

- Prompt notification of the fire department.

- Immediate five-floor evacuation of occupants (the fire floor and two floors above and below the fire floor).

- Building staff functions that complement fire department operations (communication, building service use, fire protection and life safety systems).

These factors are main ingredients in fire contingency plans developed by high-rise managers with guidance from the Fire Education Section of the Charlotte Fire Department.

The SOP, developed by this group of fire department personnel, has laid the foundation for handling high-rise fires in Charlotte. Simulated operations, coupled with ongoing training and drilling of high-rise occupants are building on this foundation If and when an actual high-rise fire occurs in Charlotte, there is no guarantee that lives will not be lost, that extensive damage will not occur, or that the fire department will not face its greatest operations challenge ever. But planning and training are helping prepare for that challenge.