BY CLARK KIMERER, CHARLES JENNINGS, and GLEN CORBETT

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 3000 (PS), Standard for Active Shooter/Hostile Event Response (ASHER) Program, 2018 edition, was released as a provisional standard, reflecting the NFPA’s sense of urgency in promulgating what it describes as the first national standard for response to such events. The NFPA, citing the continued incidence of active shooter and hostile events and their increasing magnitude, justified the process, which was used only for the second time in NFPA history.1 The NFPA Standards Council authorized the issuance of the standard according to procedures laid out by the American National Standards Institute, giving the document status as a national consensus standard. These procedures expedited the comment process.

Publication of NFPA 3000 presents many timely and important issues, both pro and con. The NFPA should be commended for taking on this daunting and complex task of establishing baseline capabilities to address incidents describable as deliberate, hostile attacks of the kind seen in Las Vegas, Orlando, San Bernardino, Newtown, Parkland, Paris, and Mumbai, sadly among many others. NFPA 3000 represents the product of a timely and critically necessary project to identify and assert standards for fire and emergency medical services (EMS) professionals responding to active shooter incidents. Although considerable work is ongoing in many domains to address the challenges of responding to such incidents, development of a framework for a comprehensive approach to active shooter complex coordinated attack scenarios is ambitious.

But, focusing on the admirable does little to address the urgent. This article focuses on the shortcomings and problematic aspects of the NFPA 3000 consensus standard, consistent with the spirit of the multidisciplinary effort that resulted in the promulgation of this standard in the first place. Engagement and deep participation will be critical to improving the document in its next version. In the meantime, there are many concerns in the implementation of the standard as it exists.

Challenges and Limitations

Although the NFPA 3000 draft purports to establish standards within the scope of its jurisdiction representing fire service and fire/EMS professionals, the draft standard in fact crosses many boundaries of jurisdiction, authority, expertise, and accountability. With its expansive approach, it is perhaps one of the broadest sets of participants expected to interact under an NFPA standard. In fact, the document anticipates a “whole community” approach.

Many sections of the draft standard are properly within the purview of law enforcement, emergency managers, law enforcement intelligence fusion centers, public health and hospital leadership, prosecutors’ offices, and elected officials, to name a few such “Authorities Having Jurisdiction” (AHJ). For example, the NFPA positing standards for functions such as crisis communication through joint information centers/systems, social media management, structuring and overseeing disaster recovery, and other well-established emergency coordination programs that are the responsibility of emergency management offices and emergency operations centers reporting to a mayor or other elected executive is puzzling on two levels: First, they are not fire/EMS responsibilities; second, and more importantly, substantial work has been done over the course of years on these and other disaster management functions and systems.

Law enforcement is responsible for, and has done significant work in, policy and training of the tactical contact team deployment and has lead roles in crime scene investigation, prosecutor interface, and intelligence fusion and information sharing, which are also addressed within the standard. There is an arguable responsibility on the part of the NFPA to confirm that involved AHJ have plans and standards in the areas for which they are responsible, but it must be remembered that the actual roles, responsibilities, and authority for those plans lie outside fire/EMS agencies’ jurisdictions. The AHJ must be governmental units, not merely agencies. The applicability of the standard to application by individual facility managers is also desirable but further clouds the identity and authority of the AHJ.

In the NFPA 3000 draft, there appears to be a conflation between partnerships and authority. The bottom line: Substantive, leading-edge planning, equipping, and training on functions itemized in the NFPA 3000 draft exist in public safety entities other than fire/EMS and reflect years of dedicated work by the public safety, emergency management, and policy level executive offices of which fire/EMS is a part and partner in a larger system.

At the risk of sounding petty, even the assertion of a rubric termed “ASHER” appears presumptuous. For police officers, nearly every event of their shift might be termed a “hostile event.” More to the point, the requirement of clearly defining every call or event in plain terms has been a hallmark of both police and fire response since time immemorial. If an incident involves a kidnapping, it is called in plain terms a kidnapping; if it is a hazardous materials response, it is called a hazmat situation. If the incident involves an active shooter, it is called without equivocation an active shooter situation. Does a well-defined arena of public safety response now require a new and rather ambiguous acronym?

Overview of the Standard

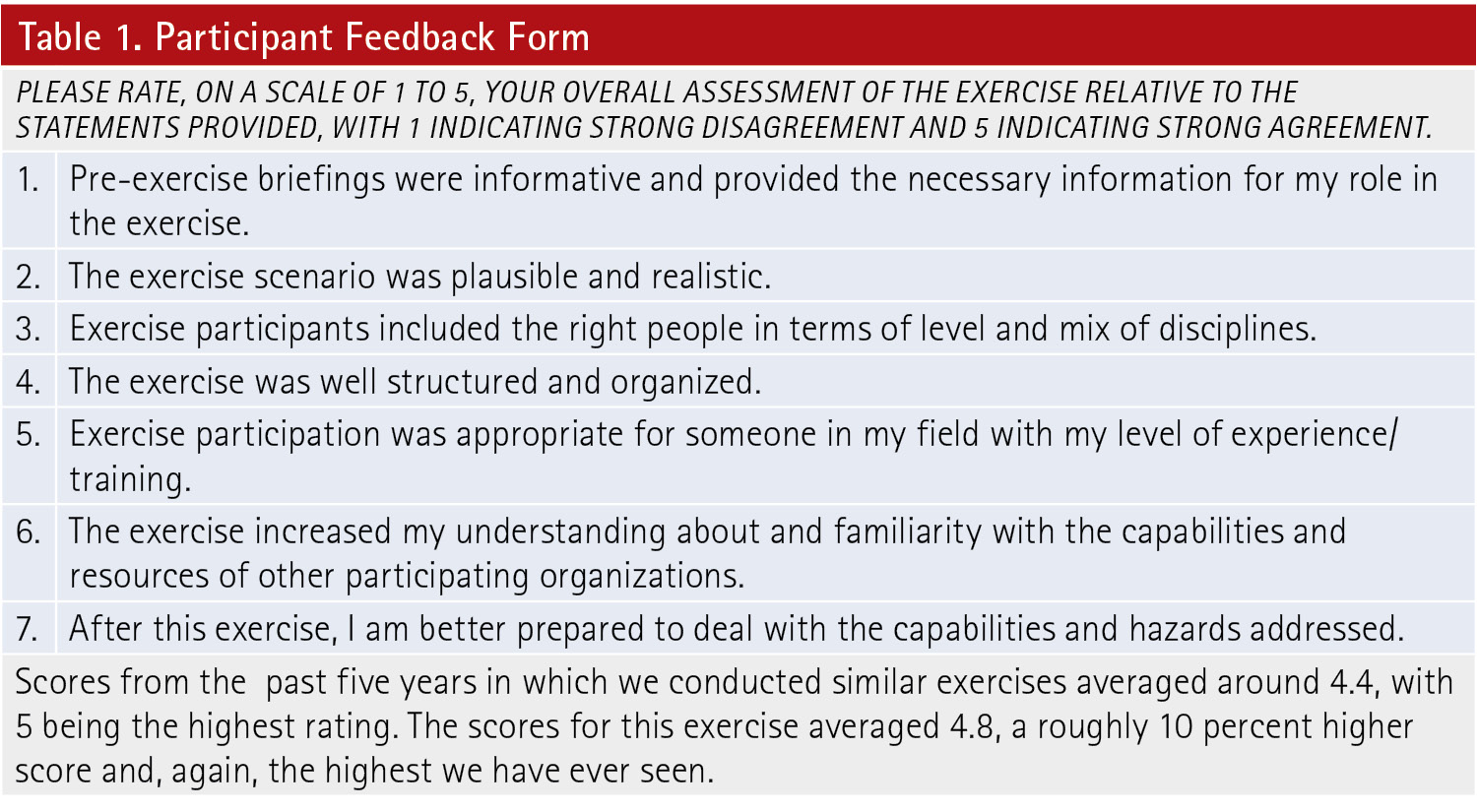

The standard is extensive, consisting of 20 chapters and three appendices. The reader should carefully peruse the entire standard, but the chapters and major requirements are summarized in Table 1.

As can be seen, the standard is very demanding and requires coordination and community engagement at a level well beyond the current capabilities of most responder organizations.

Issues of NFPA 3000 Through the Lens of the Route 91 (Mandalay Bay) Shooting

Although many of the details related to the Las Vegas mass-casualty incident of October 1, 2017, are yet to be released, there are several issues related to NFPA 3000 (and other codes and standards) that are now known and worthy of discussion. It is our intent to highlight some of these issues so that they may form the basis for future analysis and consideration when preparing ASHER plans.

Building. It has been established that the shooter, Stephen Paddock, assembled a large arsenal of weapons in his hotel room in the days leading up to the shooting. Beyond the obvious issues of hotel security weapon-inspection protocols, the high-rise hotel building itself played a role.

Paddock was able to use his elevated position on the Mandalay Bay’s 32nd floor to shoot down on the concert attendees below, across Las Vegas Boulevard, simply because he was capable of breaking through two sets of exterior windows. Although elevated positions have been used before, they are not considered in the context of NFPA 3000. NFPA 3000 views ASHER incidents with shooters (attackers) within the same relative space as the victims. It is important, going forward, for ASHER plans to consider attacks from outside the location of potential victims.

Window Glazing. Our model building codes do not consider glazing safety from a terrorist/attack, dealing simply with fire safety and glass breakage resulting from natural causes (wind, for example) and accidental breakage. We know from research of past terrorist bomb attacks that glazing plays a significant role in producing many injuries. Given the Las Vegas incident, active shooters can be added to this list; consideration should be given to upgrading our building code to address such concerns.

(1) A view from an upper floor of an adjacent hotel months after the incident, showing the concert venue site (beyond the parking garage) and the Mandalay Bay Hotel in the upper right. (Photo by Charles Jennings.)

Elevators. Despite the fact that Paddock fired more than 1,000 rounds in a relatively short time, it is remarkable that the elevator lobby smoke detectors apparently were not activated to initiate a Phase II recall. This would likely have delayed law enforcement officers even further; it is critical in ASHER incidents that properly trained/protected fire service personnel be available to operate elevators during such an incident.

Outdoor Venue Life Safety Hazards. A review of the Route 91 Harvest concert site also raises important issues on facility design and operating procedures. A review of videos and available information provides insight into what occurred within the chain link fence confines of the venues. NFPA 3000 does not directly address outdoor concert venues, including the life safety issues associated with them.

It is estimated that more than 20,000 people attended the concert; 58 people were killed and more than 500 were injured. It appears that “festival seating” was in use. The 2018 edition of NFPA 101 (the “Life Safety Code”) defines festival seating as “a form of audience/spectator accommodation in which no seating, other than a floor or finished ground level, is provided for the audience/spectators gathered to observe a performance.”

Festival Seating. For many years, issues of life safety and festival seating have been a constant source of debate, resulting in outright prohibition in some jurisdictions across the United States. Our collective history with festival seating is marked with disasters, including the 1979 “The Who” concert in Cincinnati that killed 11 in a crowd crush. Ticket sales control and crowd control have proven to be problematic in festival seating situations, leading to dangerous overcrowding. More recently, however, the popularity of outdoor concerts using festival seating, controlled through ticket sales and fences, has found more and more acceptance by local authorities.

In the 2018 edition of NFPA 101, requirements call for a very detailed “life safety evaluation” when festival seating is used. In addition, a “risk assessment” is required for assembly uses of more than 500 occupants, including the potential for requiring a mass notification system. These requirements, however, are not found in NFPA 3000.

Mass Notification. In the case of the Las Vegas shooting, it is apparent that there was no mass notification to the attendees as to what was happening as well as directions as to where to escape. Survivors have said as much; videos show attendees asking each other about what is occurring and what actions to take. It is clear that quick and clear communications, including mass notification systems as well as information from public safety organizations through social media, are essential.

Egress. The location and number of egress points played a role in the Las Vegas incident; survivors indicated they didn’t know the location of egress points ahead of time. They passed some egress points simply because their line of sight was blocked by vendor booths and other obstructions. There is also the issue of the number of egress points in large assembly venues—relying on traditional fire safety provisions (travel distance, separation of exits, and so on) may be inadequate for dealing with emergency egress during an ASHER event.

Once the survivors had escaped the concert venue itself, many of the 500 shooting victims moved down Las Vegas Boulevard. They were picked up by ambulances, buses, and private cars or simply walked away from the site. A number of bleeding victims walked into casinos and other facilities down Las Vegas Boulevard, causing occupants in some of these facilities to call 911 thinking there was an active shooter in that facility.

Mobile Injured. Traditional mass-casualty incidents (train wrecks, building collapse, for example) and NFPA 3000 treat victims as stationary; the Las Vegas shooting indicates that victims in an ASHER incident can be very mobile. Planning for an ASHER incident must prepare for such a situation.

Lessons Learned. It is critical that analyses of actual incidents inform and update codes and standards such as NFPA 3000. Although litigation and privacy issues may be roadblocks to accessing such information, it is imperative that the lessons learned from an ASHER event find their way into our related public safety codes and standards.

Law Enforcement Perspectives

Among the many important outcomes of a true collaboration to develop standards among fire, EMS, 911 centers, and law enforcement would be the establishment of unambiguous protocols to resolve what many in the active shooter expert community characterize as the “big three” issues of active shooter integrated response:

- Tactical EMS jointly deployed with police in Rescue Task Force (RTF) configurations.

- Police Contact Team Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) capability, to include bleed capability standards of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC).

- Response to multiple, simultaneous, or sequential attack scenarios, otherwise known as “complex coordinated attacks.”

In the current edition, the proposed doctrinal standard seems to be “If a Rescue Task Force (RTF) is deployed, then the following standards are to be adhered to,” deliberately making no distinction in priority between an RTF and other deployment modalities, including a victim-jeopardizing and more traditional “deliver the wounded to a cold zone for triage and basic life support” protocol. In the past few years, police agencies—as well as many fire/EMS agencies—have been aggressively exploring and, in a significant number of instances, deploying RTFs in the model of the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) paramedic programs many leading-edge jurisdictions have been employing for some time. Although we appreciate the reality that the so-called AHJ vary throughout the United States in capabilities, bargaining unit prerogatives, and other limitations, the absence of a clear statement of priority in support of furthering work to improve tactical EMS in active shooter scenarios is badly needed.

To put it plainly, it will be argued that the NFPA 3000 consensus standard deliberately avoids taking a position about what matters most, and that is the topic that currently occupies leaders and practitioners collaborating on police-fire-EMS response to active shooter/complex coordinated terrorist attack (CCTA) vectors in the United States: how to best integrate police and fire-EMS response. When the NFPA 3000 takes an agnostic position about RTF integration, care under fire, TCCC, improved first aid, and enhanced police contact team capacity to address hemorrhage and airway management, it seems to dodge the most important issue being debated today. For all the guidance about the protocols and objectives of entities who have jurisdiction separate from fire/EMS, it is puzzling that the one issue most hotly debated in public safety today—the role of police and fire partnerships in an active shooter hot zone—is given a noncommittal “if-then” treatment in the provisional standard.2

Dispatch Communications

Those who have studied the management of asymmetric attack vectors for many years share a common belief: The first entity to identify and coordinate response to a complex coordinated, active shooter or related scenario is the jurisdictional 911 call center. Public safety 911 call center leaders and practitioners have undertaken substantive analysis, training, and research toward the end of establishing protocols to address the unique circumstances of an active shooter/CCTA scenario. Again, it is problematic that this important element of active shooter incident management and response has been given short shrift in the provisional standard. As we have noted about the other entities with jurisdiction and credible authority (police, emergency management, elected leaders, hospitals/public health authorities, and so on), their prodigious work in developing response protocols to scenarios is now swept up under the “ASHER” acronym. The minimal written standards attached to the operational role of 911 call centers and the role of accrediting agencies are one of the most significant deficiencies.

CCTA and Emerging Law Enforcement Perspectives

The definition of “complex coordinated terrorist attacks” (cited here) is viewed as contrary to current thinking about this profound issue by law enforcement leaders.

A CCTA is most certainly not to be viewed as an accumulation of individual incidents connected to a common attack vector but instead is intended to disrupt systems of response that are structured to respond to multiple attacks “one at a time.” The most sophisticated law enforcement analysts of CCTA response will argue that the goal of a multiple, connected, coordinated asymmetric attack schema—like Paris or Mumbai—is to trigger response modalities that conform to the premise that multiple attacks are cumulative and must be addressed as they occur. It is precisely these predictable response patterns—which are symmetrical as opposed to “asymmetrical”—that are exploited to deadly effect.

All this being said, the substantive issue is this: The NFPA is exposed to potential objections concerning an overreach of its scope of authority. Although there are many references to the need to involve law enforcement and other public safety entities in the creation of unified standards for response to active shooter incidents, absent express concurrence by all other AHJ, it is difficult to envision its implementation. Perhaps this fact is self-evident, in view of the broad charge of the NFPA Committee of having “primary responsibility for documents relating to the preparedness, planning and response to cross-functional, multidiscipline, and cross-coordinated emergency events that are not already established by the NFPA in other codes and standards. This includes all documents that establish criteria for the professional qualifications of those who are responsible for preparation, planning, exercising, and responding to cross-functional, cross-jurisdictional events.” It is extremely broad in its applicability and could create a disconnect between the protocols of law enforcement—who has primary jurisdiction until an incident is stabilized—and the fire and EMS professionals, who are co-responders. The inclusion of law enforcement representatives on the committee is laudable, but an actual joint development of comprehensive standards applicable to fire, EMS, and law enforcement requires express authority granted by law enforcement to accreditation and standards entities. Also, 911 centers are to be included as a critical partner in this project.

In Chapter 5 on Risk Assessment, the extensive list of standards/recommendations presented has been the focus of years of work by entities with express authority to undertake analysis and develop policy and work products. Risk assessments are most often completed through the agency and facilitation of emergency management entities, with significant standards and guidelines required by the Department of Homeland Security through the Threat Hazard Identification Risk Assessment process. This same well-established and long-standing process applies to critical infrastructure analysis, GIS/situational awareness systems, vulnerability assessments, and many other complicated components of threat-based preparedness and response structures. The relevant fact remains that the majority of itemized risk assessment categories in this section are not the primary jurisdiction or responsibility of fire/EMS, except as a participant entity.

Areas for Future Attention

The NFPA standard requires considerable input and participation, particularly from nonfire/EMS organizations. Most critically, there are significant demands placed on facility managers, hospitals, and dispatch centers. The standard is also unique in that it specifies planning for long-term recovery and includes mental health services. Obtaining participation from all stakeholders will be a significant challenge for any AHJ looking to adopt the standard. Unlike many fire codes, the AHJ are clearly at the level of local government—not the fire service.

Although the NFPA made considerable effort to include diverse stakeholders, the size and diversity of law enforcement agencies, multiple approaches to tactical medical response, and diverse capabilities of fire/EMS services will likely demand considerable engagement from the affected communities and interest groups.

The standard appears to indicate that facilities or individual entities such as colleges or businesses could adopt the standard internally, but it will be challenging for such entites to implement the standard if the local emergency services and the appropriate AHJ fail to adopt the standard or participate.

The NFPA 3000 standard will be open for possible revisions in NFPA’s 2020 Revision Cycle, with the next edition of the document to be published in 2021.3 The first draft comment period closed on August 1, 2018, and the second draft comment period closes in May 2019.

The industry is learning from past events and, thankfully, After-Action Reports (AARs) have been completed for many of these events. Analysis of these reports for findings that may bear on this standard is an important task, and findings should be incorporated into the upcoming revisions of the document. Importantly, single-discipline AARs may not adequately capture challenges in coordination or may not identify limitations or problems faced by other first responder groups.4 Deep engagement by allied organizations will be necessary to make the standard more workable and reflective of emerging thought in the law enforcement discipline.

Endnotes

Clark Kimerer is a deputy chief/chief of staff (ret.) with the Seattle (WA) Police Department, where he spent more than 30 years in assignments including the SWAT team, hostage negotiation, and operations. He is an adjunct faculty member for the Homeland Security-focused Executive Education Program at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School. Kimerer serves on the advisory board of the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies. He was inducted to the Evidence-Based Policing Hall of Fame in 2014. He is on the Board of the National Association for Public Safety GIS.

Charles Jennings is director of the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) in New York City. Jennings is also program director of the College’s graduate programs in emergency management. Jennings is a former deputy commissioner of public safety and participated in development of AARs for active shooter events, bombings, and major fires.

Glenn Corbett is an associate professor of fire science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, where he is director of the Academy for Critical Incident Analysis and an advisory board member of the Christian Regenhard Center for Emergency Response Studies. He is a member of the Fire Code Advisory Council for New Jersey. He is technical editor for Fire Engineering, coauthor of the late Francis L. Brannigan’s Building Construction for the Fire Service, 5th Edition, editor of Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II, and an FDIC executive advisory board member. He is a former assistant chief of the Waldwick (NJ) Fire Department.