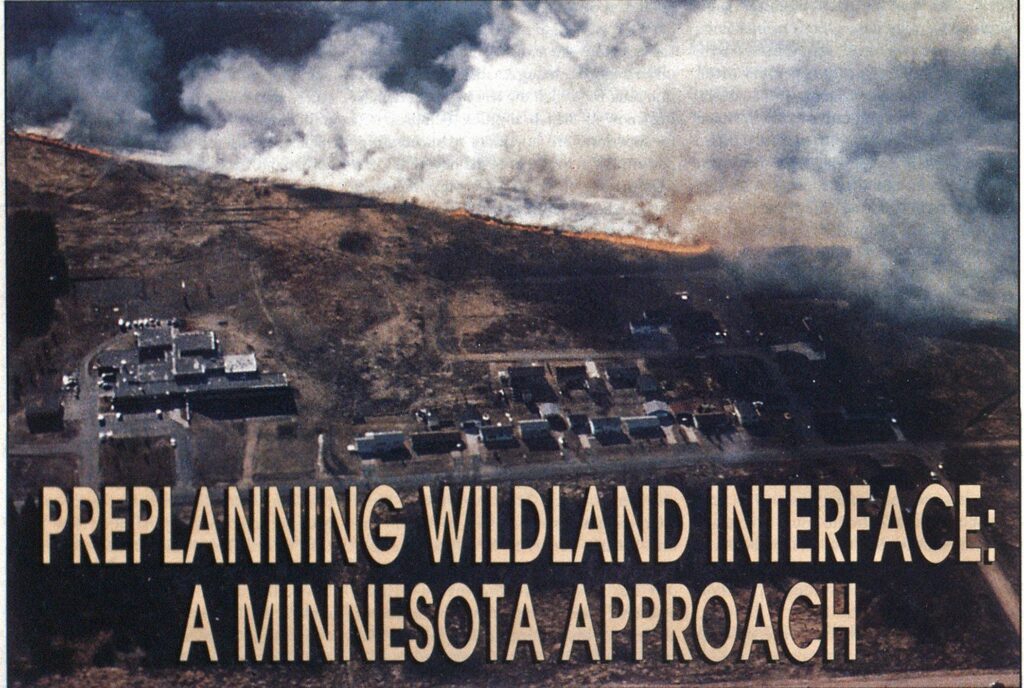

PREPLANNING WILDLAND INTERFACE: A MINNESOTA APPROACH

(Photo courtesy of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.)

On Mother’s Day 1992, a pair of winddriven wildfires in northeastern Minnesota blackened 9,000 acres and consumed 37 structures in a single hot afternoon. The fury of these twin blazes can be gauged by the fact that the fires spread so rapidly over essentially flat terrain. Amazingly, no one was killed; but dozens of agencies, including the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the U.S. Forest Service, and several volunteer fire departments, took grim note of the harrowing possibilities. That included us, the French Township (MN) Volunteer Fire Department (VFD), a small rural organization with 17 members.

We learned that one of the Mother’s Day fires was ignited by a downed power line (the other was suspected arson); and we realized that a power pole could just as easily have tipped over in our bailiwick, with the same, or much worse, consequences. French Township is a lakeside vacation/bcdroom community sporting 700 residential structures concentrated in the very midst of dense fuel—forest and brush—served by a confusing network of narrow, winding roads and drives.

We conjured up a vivid image of potential disaster; and in light of the Mother’s Day incident (which unfolded only 25 miles away), we decided to develop a preplan to help us mitigate the impact and serve us through the initial attack stages of “the Big One.”

The essence of fireground operations in the rural/urban interface is interagency cooperation, as was clearly demonstrated by the November 1993 conflagration in southern California. Large, fast-moving wildfires do not respect jurisdictional boundaries; and it would be futile for a single agency to assume sole authority and control over the planning process.

PRELIMINARY PUNNING

With that in mind, we assembled a fourperson preliminary planning team consisting of two members from the French VFD and two local representatives of the DNR Division of Forestry, the agency bearing ultimate responsibility for wildland fire suppression in most of Minnesota.

Our first meeting was a freewheeling brainstorming session, focusing on and directed by a large wall map of the area on which participants were free to write and sketch. The trickiest aspect of any complicated planning process is simply getting started, since the project seems at first blush to be so vast and unwieldy. We broke the ice by dividing the map into quadrants along prominent boundaries (a river and a highway) and handling the delineated precincts one by one. The task was thus rendered significantly more manageable by two lines drawn on the map.

Our first goal was to pinpoint the following locations for each quadrant:

- Potential staging and/or incident command post sites. For example, in our NE Quadrant, there is a community center complex that includes a parking lot and ball field and, not insignificantly, a telephone and rest rooms. The open area is expansive enough to stage several dozen fire rigs.

- Safety zones. During the Mother’s Day incident, a handful of people were cut off by crown fire and retreated to a gravel pit to escape the flames. Our NE Quadrant has such a pit, plus a relatively large cleared area at a dumpster and recycling site.

- Water sources for pumpers and tenders. In northeastern Minnesota, there’s water just about everywhere; but we designated more than a dozen bridges, beaches, and culverts where drafting operations and/or floating pump operations can be established with minimal effort.

- Special problem!hazard zones. Our NE Quadrant, for example, includes a small sawmill/lumberyard business that presents an especially heavy fuel load, a power substation with the potential for electrocution and toxic smoke, a summer camp that could produce an evacuation challenge, and several dead-end roads that twist through volatile forest fuels.

- General wildland fuel characteristics. For the NE Quadrant, those characteristics include a sandy pine ridge with numerous

(Photos by Tim Russ.)

- plantations and a wide expanse of essentially unbroken fuel to the northeast.

IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

Once each quadrant had been analyzed in light of these parameters, the information base was used as a guide to develop our standard operating guidelines for implementing the plan. We instituted the following “doctrines”;

- Unified command. Any large incident— probably involving both wildland fuels and structures—will be supervised by a tandem of incident commanders, one from the DNR and one from the French VFD. Though sharing overall authority, each will be responsible for specific aspects of the incident; for example, incoming mutual-aid fire departments will contact the VFD incident commander, and incoming DNR (and Forest Service) units will initially contact the DNR incident commander—on separate radio frequencies. The VFD incident commander will work on the Minnesota Fire Mutual Aid channel, and the DNR incident commander will use a DNR tactical channel. A notable lesson of the Mother’s Day fires was that you can’t have too many channels. Radio traffic at that incident approached gridlock within minutes, and communications was the major hassle. So that communications will be facilitated, our plan stipulates that the two members of the unified command work at the same post. It was suggested they be handcuffed together by the first-arriving law enforcement unit, and the remark was only half in jest.

The “one 1C with two heads” concept is used in the critical initial stages (the first few hours) of the incident, when the situation is at its most dynamic, fluid, and confused, so that the local agencies can manage their resources to the expedition of a shared attack strategy. When the “overhead team” from the state arrives, a complete command module—with only one incident commander—is implemented.

To help temper the confusion that often plagues initial stages of a large incident, we also created a command post/staging area kit. to be stored in a fire-ready condition at the local DNR field station. The kit includes high-visibility ICS vests for the incident commanders and staging personnel; several copies of the preplan and its accompanying map. to be distributed to incoming mutualaid officers; and field office supplies such as clipboards, notepads, and grease pencils.

- Flexibility of implementation. The decision to set the plan in motion—that is, establish the unified command, will be made by the initial attack incident commander at a given fire. It’s most likely this will originate with a DNR employee as fire spreads out of control from wildland toward or into structures. The command “Activate the emergency action plan” will be transmitted to DNR dispatch and relayed to the French VFD. If the fire is spreading from a structure(s) to wildland in an uncontrolled manner and the initial attack incident commander is a VFD member, the same command would be transmitted to DNR dispatch. The plan also could be implemented in anticipation of a major incident before rapid escalation occurs; either agency has the right to call for the establishment of the unified command.

- Preordained, preassigned radio frequencies and radio protocol. We denoted nine radio frequencies to be used in conjunction with the plan, assigning functions and prohibitions to each. It is emphasized, for example, that the main dispatch channel (our countywide 911 system) will be used only to acknowledge a page, inform of response, and request additional resources; it is not an operations channel. Any VFD

- involved will work on the Fire Mutual Aid frequency, and any DNR/Forest Service units will work on one of their tactical channels. It’s understood there will be mixing of resources on the fireground, and potential players have been encouraged to install all nine frequencies in their radios. The plan recognizes that a large incident will likely be broken into divisions or sectors based on convenient geographical bounds—perhaps our specified quadrants—and that, ideally,

- each division or sector will be provided with its own operations frequency.

- Prepositioning of resources. On extreme fire days, as determined by DNT-calculated indices, provision is made to preposition local fire suppression resources to attain maximum readiness. On the morning of the Mother’s Day fires—already hot, dry, and gusty by 9 a.m.—we all knew “something’s going to happen”; the only questions were when and where. Our plan encourages vol-

- unteer firefighters to stand by at the fire hall while possibly being paid an hourly wage by the DNR, as outlined in an existing contract between the French VFD and the state. This would make it easier for volunteers to justify a further substantial commitment and perhaps time off from a regular job.

- Flexibility of roles. The plan notes that, during an extended major incident, local emergency personnel—both DNR and VFD—may be shunted into positions other than fire suppression. People familiar with local roads, fuel types, and hazard areas may be better employed in evacuation operations, as guides to incoming mutual-aid units, field observers and scouts, or staging managers.

- Air operations subject to a single authority. In this case, all fireground air operations—helicopters, air tankers, lead planes—will be under the direct control of the DNR, via an air attack supervisor reporting to the unified command. The agency has considerable expertise in fireground aviation. Potential helibases and helispots also are designated, especially for medevac requirements.

- Wide distribution of the plan. All likely players have been provided with copies of the plan, which includes a map. list of radio frequencies, critical telephone numbers, and an ICS flowchart of the organizational structure to be set up by the unified command. Also, via press releases and personal contacts, the planning team generated news stories in local and regional media that stimulated further interest in the plan among fire service colleagues who might be involved in an actual incident. Publicity also informed the general public and, frankly, lent increased credibility to the efforts of a small rural volunteer fire department. In addition, fire organizations in other areas were inspired to begin work on their own plans.

- Peer review. After the four-person team wrote a first draft of the plan, the draft was circulated to all members of the French VFD and local employees of the DNR. actively soliciting critiques and input. This resulted in a second draft that was submitted to DNR fire officials at the regional and state levels. Subsequently, a meeting was convened between the original team and 10 DNR personnel with considerable fire suppression and fire administration experience to finetune the plan and hammer out a final draft.

But to be fully effective, a plan such as ours must be rehearsed; and we recently conducted our first practice session. Proceeding from the conviction that communications and interagency coordination are at the heart of a major incident preplan, we designed a basic radio drill involving the French VFD, the DNR, and four of the mutual-aid departments we’d be likely to call on first. We set up a staging area and a mock incident and then had each unit dispatched. The idea was that responders would practice using multiple frequencies, learn what to expect when they pull into a staging area, and test the collective radio capabilities.

(Photo courtesy of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.)

(Photo by Tim Russ.)

Each department was to acknowledge its initial page on the 911 channel, then switch to the fire mutual-aid frequency to report its ETA to the staging officer. After staging logged them in at that location, each unit (average three rigs per department) briefly informed 911 of its arrival at the scene. The mock incident was about two miles from staging; and as the 1C requested resources at the “fire,” the staging officer informed each departing unit to contact the 1C on a DNR tactical frequency, which served as the designated fireground operations channel. Thus, responders were required to manipulate three frequencies, switching from one to the other for specific, predetermined reasons. It was a purposely simple beginning, because we know from experience that many volunteer firefighters are intimidated by radios and are unaccustomed to multiplechannel operations.

Our next drill is designed to build on this first practice and will involve live fire at two locations and more than one operations frequency. It will combine communications with water transfer mid actual suppression, and we’ll invite law enforcement and EMS units into the training loop. A basic helicopter briefing (landing /.one setup and safety) is also scheduled, since any major rural/urban interface fire is likely to employ mi aviation component.

LESSONS LEARNED

- The development of the plan was in itself a valuable educational experience. Focusing so intently on the potential hazards (and potential assets) of our area in light of “the big one” afforded us all a fresh perspective of the locale we protect.

- Effective communications are paramount, and basic radio protocols need to be rehearsed. Also, as many frequencies as possible must be made available.

- A preplan can be too detailed and unwieldy. Allow for flexibility of roles and implementation. The inevitable turmoil of the fireground will demand modifications to any plan. If the final planning document is too thick, few will read and absorb it anyway.

- Keep the initial planning team small. It would be easy to have too many people involved at this stage and to get bogged down in details. After a first draft is available, circulate it widely to gamer informed input.

- It is important to include field personnel on the initial planning team. This is not a project that should be restricted to the influence of the “big dogs.”

- The development and rehearsal of the plan have fostered closer personal ties between the officers and personnel of the various agencies involved. It’s impossible to overemphasize the importance of being able to assign a face to the voice you’re hearing on the radio or names to the colleagues sharing the fireground.