RESCUE ’90: THE “BIG ONE”

RESCUE

Photos by Karl Marzolf, Becky Spicer, Sheldon Levi, ond Frank Borden.

The call we received was for a series of major structural collapses in the Silver Spring area of Montgomery County, Maryland. Because of very poor communications from the Washington, D. C. area, we were not exactly sure what had caused the disaster. Rumor had it that a relatively minor earthquake had caused a major gas explosion.

We assumed that the residential buildings involved were fully occupied, as the collapse occurred at 1 a.m. on a Sunday morning. Again, the best information available to us indicated the possible involvement of thousands of victims. Information concerning local fire/rescue/emergency services was not available.

We did know that the county contacted the Maryland Emergency Management Agency, which contacted Maryland Governor William Donald Schaeffer, who requested direct rescue support from FEMA Region III. FEMA Region III contacted FEMA, which through the national Urban Rescue Task Force program mobilized six task forces of 56 personnel each to respond.

The task forces were taken from six different locations throughout the country, including California, Alaska, Puerto Rico, Florida, New York, and Arkansas, in order to lessen the impact on any one geographic area. The Department of Defense provided transportation, and some of the task forces arrived within five hours of FEMA’S request.

Each task force was prepared to be self-sustained for 72 hours and to work around the clock for that period of time. Each one was self-contained in terms of expertise and equipment.

Each task force had a leader and an assistant leader who had experience leading large groups and had a teambuilding background to facilitate a team effort in the worst possible disaster conditions. In addition, each had a Department of Defense liaison to expedite any additional and long-term needs. Teams also had search dogs and handlers and personnel trained in the use of seismic and acoustic devices to locate victims. There were structural collapse and heavy rescue specialists, doctors and paramedics, and personnel specializing in structural engineering, heavy equipment, hazardous materials, safety, communications, and documentation. All were cross-trained to the greatest extent possible.

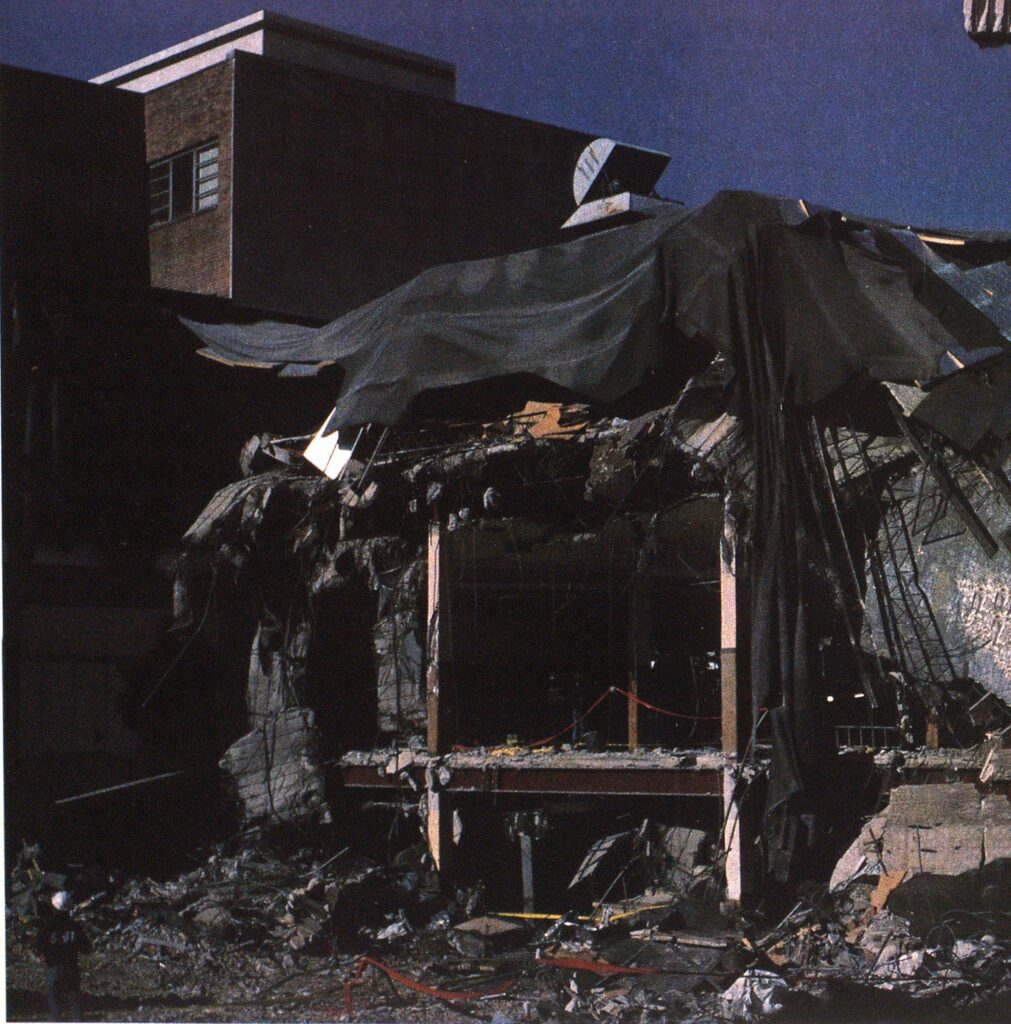

As the first task forces arrived in Silver Spring via military transport, they saw several blocks of destruction and, most noticeably, a crater in the center of one block with partially collapsed sixand seven-story buildings surrounding it.

The briefing at the command post revealed that the explosion had a significant impact on the Montgomery County Department of Fire and Rescue Services and the quake had caused damage to other neighboring jurisdictions. Initial damage reports indicated that at least 100 structures were heavily damaged.

The six task forces were assigned to work in the several-block area surrounding the crater, and the estimated population of their assigned area was 10,000. The Montgomery County incident commander assigned each task force a sector in which to operate. The media was anxious for information regarding the incident and was crowding around the command post and media officer.

Later that morning, Grant Peterson, associate director of state and local programs and support for FEMA, toured the disaster site with other state and local government officials. The local, state, and federal government cooperation and support during this incident were tremendous.

A TEST!

This incident was a test! Students participating in Rescue ’90, the International Seminar on Urban Rescue and Structural Collapse held in Montgomery County, Maryland, had the unique opportunity to operate under the proposed FEMA task force system on a sustained urban rescue incident.

The “Big One” was held the last day of this four-day event and gave participants an opportunity to practice what they learned. The instructors became safety officers and advisors and the students were not only the technicians but also the decision makers.

The idea for Rescue ’90 was developed over a year ago as a result of urban rescue training concerns that the Montgomery County Collapse Rescue Team had because of the rapidly developing field. National awareness and interest in this field was growing. At the same time FEMA was working on a program for national response to catastrophic disaster that would involve fire/rescue and emergency services throughout the country.

We developed a planning committee of 15 people with diverse emergency services backgrounds and began meeting weekly. We needed to develop an underlying philosophy for the seminar, so we gathered lists of concerns. We talked to as many components of the “system” as possible, including search dog handlers, structural engineers, medical personnel, government agencies, and construction industry representatives.

We found several common threads throughout our discussions—probably the most recurrent was the concept of team building. We all agreed that the most important underlying factor in any type of disaster response was the ability of individuals to work together as a team. We also were aware that urban rescue programs did not emphasize the team enough. The program development committee agreed that the focus of the seminar should be team building.

The second most common concern was incident command, closely followed by safety issues. The committee agreed that we would emphasize the National Fire Academy Incident Command System and scene assessment and stress safety issues throughout Rescue ’90.

The planning committee selected instructors based on previous contact. We all had a broad base of experience in the urban rescue field and as a result were able to identify the best instructors. They came from 32 states, Canada, and Puerto Rico.

Our next concern was to make sure that the instructors taught within the guidelines of the seminar as we had designed it. We knew that we had developed an ambitious program and that to meet our goals we had to keep tight control over content. We decided to write objectives as we envisioned them for each topic and then send them to the lead instructor for input. We worked with the instructors until we all were comfortable with the final objectives.

To the best of our knowledge, never had such an ambitious training effort been undertaken in the history of emergency services: 300 hands-on participants would spend three days being introduced to the components of the Urban Rescue Response System, and that experience would culminate in the “Big One.” It was not our intent to be an allinclusive, “spend four days in Maryland and be an expert” seminar. We did want to “whet” the students’ “appetite” and illustrate the magnitude of the commitment for a jurisdiction to become involved in the National Urban Rescue Response Program.

We hoped that students would take home information on each element of urban rescue response and that they would either demonstrate to their agency that they were on target or realize their deficiencies and adjust before their commitment became too great.

We felt that our collapse rescue team also would gain from the experience. The thousands of hours of work involved contact with the best instructors in the United States, and it allowed our team contact with all elements of the National Urban Rescue Program.

As we developed the program, someone asked, “If this is such a great program, why hasn’t it been done before?” From that question we developed our motto: “Rescue ’90 —the impossible task!” The key to tackling a program of this magnitude was to break each component into “bitesize” tasks. We also utilized the NFA Incident Command System early on in the program development. Task assignments were made based on ICS.

THE SPONSORS

The 19 corporations of the Montgomery’ County Fire and Rescue Services provide service to more than 700,000 citizens in the 600-squaremile county. The 700 active volunteer personnel staff 36 stations. Under the leadership of Director Ramon Granados, the department has 900 career personnel who support the corporations and the fire and rescue commission.

With Granados’ encouragement, the department hosts a number of national fire/rescue and medical conferences each year. The tremendous support of the director, of Assistant Chief MaryBeth Michos, and of the staff for unique continuing education experiences makes seminars such as Rescue ’90 a reality.

In addition to the Montgomery County Collapse Rescue Team personnel, our staff included members of Baltimore County; the U.S. Disaster Team. Canine Search and Rescue Unit; and the Virginia Beach Fire Department, whose batallion chief, Chase Sergeant, served as task force coordinator. This important position assured the task force leaders that a chain of command (again, within the NFA ICS) existed for dissemination of information from staff to students. Once again, based on the “team building” concept, it was up to the group leader to pass on information to the rest of the group.

The International Association of Fire Chiefs provided tremendous administrative support throughout the planning phase. Our relationship with the IAFC and IAFC Urban Rescue and Structural Collapse Committee certainly enhanced our program. Gary Briese, executive director of the IAFC, acted as seminar facilitator. He was a fine example of how a good facilitator can enhance a program.

FHMA, through Larry Zensinger, expressed support for the program from the onset. We wrote an “unsolicited proposal” to FEMA and received a grant to assist with instructors’ expenses.

SEMINAR DESIGN

It was our intent to provide the most comprehensive seminar in the allotted time. We wanted to make the seminar available to both career and volunteer personnel who have varying degrees of support from their employers.

We also were concerned that the cost be low enough to encourage attendance from people with varying degrees of financial support. To this end, the chiefs of the Montgomery County Fire stations provided bunks for those whose budget wouldn’t allow them to stay in the conference hotel.

The seminar was designed so that students would spend the mornings in the classroom and the afternoons in the field at work stations. The last day was the “Big One,” followed by a critique.

The seminar started with several motivational talks, including a presentation by Congressman Curt Weldon.

The students broke into task forces. Each student was assigned to a task force prior to the seminar based on experience and information sent back with the seminar registration form. From this point on the students were expected to operate as a task force and they did all activities together. To further promote team building, a professional team-building organization, Cradle Rock Outdoor Network, put the students through “ice-breaker” exercises and conducted basic teambuilding drills. The groups elected leaders for the duration of the conference and it w^as up to each group to further develop the chain of command.

This exercise was very similar to what would happen during an actual disaster —many people and groups coming together but without a developed team. The first undetermined period of time would be spent organizing and developing leaders.

In setting up the teams, we were careful to separate those from the same organizations. The committee felt strongly that the tendency to stick together should be discouraged and that students should be placed in a new environment to enhance the team-building concept.

All students received a conference notebook to take back to their organization. This notebook is three inches thick and contains 12 sections. Many participants remarked it was the most extensive course material they had ever received at an educational seminar.

Thanks to each of the instructors, the notebook is the most comprehensive collection of urban rescue information available today. In maintaining the team-building concept, the notebook contains a section entitled “Networking.” This section contains the names and addresses of every instructor, staff member, vendor, and participant at Rescue ’90. We hope that this section will encourage further communication among all personnel involved. It increases the potential for overall positive impact on the urban rescue environment. We will make additional notebooks available to those interested at a nominal cost.

LECTURES

Morning lectures included a number of general sessions relating to the urban rescue community and more specific lectures relating to afternoon hands-on sessions.

The general sessions included presentations by Larry Zensinger of FEMA on the Urban Rescue Response Program; Larry Greene, division chief of the Fullerton (CA) Fire Department, and Chief Frank Borden of Los Angeles City Fire Department on the incident command system; Ralph Wilfong of the Virginia Department of Emergency Services on logistics; Lieutenant Carlos Castillo, director of international programs for the MctroDade County (FL) Fire Department, on types of disasters; John Carroll from Metro-Dade on communications during disasters, the importance of task forces being self-contained, and the use of satellites; and Beth Barkley from the U.S. Disaster Team on international and multicultural communication.

The lectures relating to the handson sessions included presentations by Dr. Richard Kunkle, from the Special Medical Response Team (SMRT) in Pittsburgh, on crush syndrome; Dr. Joseph Barbera, also from SMRT, on his patient care experiences during the Philippines earthquake; Dave Hammond, a structural engineer, on building construction and failure during an earthquake; Bob De Benedictis, a crane rigging and safety specialist, on the use of cranes and related safety concerns; and Shirley Hammond, from the California Rescue Dog Association (CARDA), on the use of properly trained search dogs in urban rescue.

HANDS-ON SESSIONS

Each afternoon the task forces went by bus to their work stations. The Red Cross provided lunch there and used Rescue ’90 as a training exercise as well.

The rubble piles used at various stations were made up of demolition debris that our Logistics Branch gathered and had trucked to our sites. For the conference we built four piles in all. Some of the rubble piles were temporary and had to be removed after the seminar. This involved moving more than 120 truckloads of debris and six concrete double-Ts, which had been shipped in at no charge. All of the debris was removed at no charge in just two days.

At the Training Academy we used an existing training tower but designed and built a permanent structural collapse, confined-space training site with donated building parts. This structure allows students to breach walls and floors and stabilize significant pieces of the structure in a relatively safe environment.

The hands-on stations included most of the components of the proposed FEMA system. Participants spent two hours at each station for an orientation lecture and hands-on activity.

Each station had a lead instructor and adjunct instructors. One of our concerns in providing a hands-on experience for 300 students was the student-to-instructor ratio. We tried to keep the ratio at one instructor for every five to 10 students (depending on the topic).

At the Dogs and Devices station, students worked with victim detecting devices in a rubble pile. The station was set up so that victims could be safely hidden. It was led by Jeff Kravitz from Mine Safety and Health Administration and Shirley Hammond of CARDA. Students also worked with and around search dogs. The fire/rescue community has not yet fully realized the value of properly trained search dogs in the structural collapse environment. This station gave students a chance to see the dogs in action.

1’he Victim Handling station w as at our permanent structural collapse training site at the Training Academy. Students proceeded through a group of substations on atmospheric monitoring, basic life support, and advanced life support skills. The students were able to practice victim removal on rubble and in confined spaces.

At Ladder Rescue Systems, a station led by instructor Jim Hone from the Santa Monica Fire Department, students practiced rescue and patient removal techniques using equipment commonly found in any fire department. The exercise was held at the Training Academy’s seven-story training building.

At the Collapse Stabilization station, led by Bob Samuelson from California and structural engineer Dave Hammond, students saw static displays of building stabilization techniques utilizing timbers, cribbing, and Airshore at a small, one-story undamaged structure. Then at a rubble pile containing large slabs and several crossed double-Ts, students practiced stabilizing the slabs and Ts as if they were part of a larger structure.

The Heavy Support Equipment station was led by Captain Mike Hamilton from the Montgomery’ County Collapse Rescue Team and Jim Gregory, the owner of Digging and Rigging, a Maryland crane company. They introduced students to heavy cranes and lifting techniques as well as safety considerations when using cranes in rescue. Students also saw other types of heavy equipment for use in the urban rescue environment, including double-Ts, slabs, and commercial and homemade anchors. Digging and Rigging also provided two cranes for this station and for the “Big One.”

The most diverse station was Hand Tools, led by Captain Ray Downey from the City of New’ York Fire Department and Battalion Chief Mike McGroarty from the La Habra (CA)

Fire Department. The students were divided into subgroups and rotated through work stations to use tools supplied by the vendors. They worked on a rubble pile with Ts and slabs spread over a large area.

Students used hydraulic rescue tools, torches such as the plasma cutter, airbags for lifting, and tools for breaching concrete. Most of the tools were self-contained and self-powered for use in the urban rescue environment.

We set up a vendor tent in which vendors sold tools and spent time with the students. More than 40 vendors participated. Students went home with a great deal of specific tool information as well as hands on-experience. Packets of vendor information were given to each student at registration.

OBTAINING THE SITE

Sergeant Mike Lavelle of the Montgomery County Collapse Rescue Team (CRT), an active member of the planning committee, masterminded the “Big One.” The CRT has a good relationship with the County Permits Department, which issues demolition permits, so the team receives a copy of each permit issued. Over the past several years we have been fortunate to have had access to approximately 15 structures under demolition for team training. The process required to put one of these drills together is long and difficult. Approximately 50 percent of the structures we sought we never received.

When we hear of an upcoming demolition we rarely have more than three weeks notice —the norm in the demolition industry’. First we must look at the structure and determine whether it meets the team’s current training needs. If it is usable (reinforced concrete, masonry’, large or curtain construction), we will pursue it.

The problems are many. Is the building owner willing to allow’ us to work in his building under demolition? This usually can be determined by a face-to-face meeting at which we show the owner articles w’ritten about previous drills and slides of the actual exercises.

The next problem is receiving the cooperation of the demolition contractor. Contractors normally want to enter the building and take it down as quickly as possible to lessen liability for the partially demolished structure and allow time for more jobs. We also meet with them and ask them if we can work in the evening or on a weekend. Most of our training at structures has been on weekends.

In most cases the contractors become so involved that they attend the drill themselves. This is good from a community relations standpoint and from a safety standpoint should something bad happen. We have now developed a good relationship with the largest demolition contractors in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area.

Legal concerns—relieving the owner of liability—can be solved by drawing up a “hold harmless” agreement. It was difficult determining how to hold harmless for 450 students and staff— mostly non-Montgomery County participants—but once the building ow ner and demolition company agreed, we had our site: a group of six-story buildings under demolition. Could we work 300 students and 150 staff members in a site of this size? To the best of our knowledge, it had not been tried before.

Sgt. Lavelle met with the demolition site manager and made drawings of the site as work progressed. He felt that the square-block site would be sufficient.

FINAL PREPARATIONS

We notified the county police so that they could block off the proper streets and in case the public thought that it was a real incident. In addition, we notified all utilities of the upcoming event.

Washington Gas Company approached us to use the “Big One” as an activation drill for their personnel. So Sgt. Lavelle built a gas leak into the scenario. Gas company safety personnel ran a line of compressed natural gas from a small container into the site. They used real gas so that the monitoring equipment of rescue personnel would work. The situation was closely monitored by gas company safety personnel.

We identified various locations to place victims. In areas where live victims would not be safe, we buried tires. Tires marked with fluorescent paint represented live victims and unmarked tires represented dead victims.

We would carefully place live victims in various rescue scenarios and assign each a safety officer. This was done under the direction of Sergeant Joe Hiponia of Montgomery’ County and Special Medical Response Team personnel. In addition, we gave each victim a card that said “EMERGENCY” on it. In case of a real emergency, they would raise the card so rescuers would know they were not simulating their injuries.

The day before the drill the staff traveled to the site to review the plan and the hazards associated with the structures in daylight. At night they made a final check to ensure the site was stable. They marked off unstable areas with barricade tape and told students that those areas were offlimits. This demonstrated our commitment to safety.

That night the students attended two lectures and a briefing. This served many purposes. Mainly it kept people from spending the evening in the bar—we emphasized that any indication of intoxication would forfeit the students’ right to participate. We also addressed safety concerns at this time and presented the general rules of the exercise. We tried not to reveal too much detail.

Students were dismissed at 10 p.m., not knowing that the first activation would occur at 3 a.m. Chase Sergeant notified each task force leader at 30minute intervals starting at 3 a.m. It was up to the leaders to have developed a system to notify the rest of the group for response. They had 45 minutes from initial notification to be ready for transport by bus to the collapse site.

THE “BIG ONE”

When students arrived on the scene, the command post already was set up at the site as if the local jurisdiction had done so. This showed students what they typically can expect to find when they respond to other jurisdictions.

Lieutenant Carlos Castillo from Metro-Dade served as our local incident commander. He was assisted by Gary Briese from the IAFC and several others.

The command post communications system was set up by John Carroll from Metro-Dade, Mark Deputy from the Montgomery County Emergency Communications Center, and the local telephone company. These personnel did a tremendous job in establishing not only radio communications but also satellite and telephone communications between each of the sectors. The telephones allowed sector-to-sector hard-wire communications to lesson the radio traffic.

In one drill scenario, an eyewitness briefed the team, saying that there were six to 10 victims unaccounted for in the area. The team established its own command post so the task force leader had a base from which to assign tasks. They determined, after size-up, that their main challenge was gaining entry into the building. The task force leader assigned various tasks to various parts of his team. Some team members breached a wall with power tools. Others used a tower ladder to gain access to the roof, where they broke through to search for victims. Still others removed metal slats covering an air-intake vent. While these means of entry were time-consuming, students learned that these often will be their only options. Once the team penetrated the building, search dogs were sent in and were very effective at finding victims. Teams treated victims, packaged them, and lowered them down a ladder in a litter basket.

In another scenario, teams had to breach a cellar to find victims. After using tools to dig through the floor, they lowered a portable ladder down the hole for search personnel. After finding victims, they set up an A-frame with a hauling system on it to raise victims through the hole in baskets. They eventually lowered a search dog down to find additional victims. On the second floor of this building the team found a victim and had to stabilize the hall leading to her. The victim was buried in such a way that they had to carefully cut wood out from around her body, which took some time. It was during their operations that debris began falling down from the roof. An air horn sounded in their immediate area, alerting them to danger and warning them to suspend operations. When it was safe to continue working, they resumed their rescue efforts. The number of victims in this scenario provided many chal* lenges. One victim was buried under a collapsed portion of the building, another was trapped under a staircase, and a third was hidden behind a wall.

A third scenario involved an office building with trapped workers. Teams were told they had to remove victims by external means—without using the stairs. Students searched long halls, stabilizing and shoring as they went. They also did selective debris removal. Their rescue efforts involved a crane, ropes, and rigging. They lowered victims out of windows and down ladders and used a crane for a roof and a window rescue.

In each of the scenarios, more than one team worked the area. The drill was designed this way so students could practice relief and rotation of members.

SAFETY

Safety was one of the primary concerns of the seminar. Under the direction of Deputy Chief Ted Jarboe, Lt. Tom Musgrove, and Rockville Volunteer Fire Department Chief and gas company safety supervisor Alan Hinde, we covered all aspects of safety-

As Lt. Musgrove stated at the critique, “To have spent four days working long hours with 450 personnel and for the only injury to have been a twisted ankle—which did not require medical attention—the record speaks for itself.”

Several safety mechanisms were in place throughout the conference. For one, a real rescue team was standing by. Also, the Montgomery County Collapse Rescue Team had been concerned about protecting rescuers’ heads. Since most available helmets are not comfortable enough to be worn for extended periods of time, rescuers tend to take them off. Also, when working in confined spaces, rescuers tend to take their helmets off because they’re too bulky. We worked with Pacific Helmets from New Zealand and designed a lightweight Kevlar compact rescue helmet. To illustrate our commitment to safety, we provided each student with a helmet for attending the conference. By doing this we hope to enhance rescuer safety throughout the country.

Another component of rescuer and victim safety involved the use of a universal danger signal throughout the seminar. All safety personnel were equipped with (canned) boat air horns, and the students were taught that a sustained blast on the horn meant that danger was imminent and that they should seek a safe environment. During the exercise the horn was sounded to warn a particular sector of falling debris. Students heeded the warning and temporarily suspended operations.

In Montgomery County we have had this system for a number of years —using apparatus air horns to alert personnel to clear an area because of imminent danger. It works well, it’s cheap, and it’s lightweight and compact!

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

We think the proposed FEMA task force worked well. The teams had enough personnel to operate without having to call for additional help.

After the event we held a critique. The attendance was close to 100 percent. The feedback was positive and constructive:

- We didn’t charge enough for this event. Our expenses to date exceed S85,000. At the critique, participants said that they would pay more for this seminar and that it should be longer— maybe a week long—if it were held again.

- Devices or dogs alone are not the most effective search method, the students at the Dogs and Devices station found. An effective search involves a system organized by the ICS that uses witnesses, a visual recon, and the combination of dogs and devices. No single tool will work 100 percent of the time.

- The relationship between fire/rescue personnel and search personnel is still developing. Each uses an organized but varying approach to search and rescue. Rescue ’90 allowed the two groups to work side by side and experience and learn from each other’s work methods, perhaps for the first time.

- In some cases dogs wore not used when it was obvious that sending them in for initial victim search would have paid off and saved time.

- Students wanted more hands-on time, especially at the Collapse Stabilization and Hand Tools stations. They had little background in collapse stabilization and there is so much to learn that students easily could have spent a full day there.

- The students never identified the gas leak because they didn’t do a full scene assessment. On arrival they reported to the incident commander and were assigned to a sector. This procedure simulates real life: We report for duty and are told where to begin searching. But by not doing their own scene assessment, the students missed the gas leak.

- One student reported to the bus for transport to the incident with alcohol on his breath. He did not participate. We told him we were very serious about the potential danger to rescuers and victims. He agreed with us.

- Teams complained that they spent a lot of time waiting around; especially in staging and rehab. This is true to life. At real incidents teams spend a lot of time waiting for assignments.

- Tunnel vision was a big problem. In several cases teams breached a wall or floor, located one victim, and stopped searching to administer medical aid to the victim. In those cases seriously injured victims were nearby but not searched for. The students involved learned the importance of triage: Don’t stop at the first victim you find. Chances are there are more close by that might need more immediate attention.

- In some cases teams did not fully utilize their personnel. Personnel should be cross-trained. Search dog handlers or device operators should be given other tasks and should not just be waiting around for a search.

- There is a need for a universal language, and it starts with the ICS. Different departments operate in different ways, and participants had varying degrees of knowledge of the ICS. This impacted how the task forces operated. Departments need to train on the national ICS.

- You have to be prepared during training of this magnitude for a real emergency. We had a rescue team prepared to respond that was to gather at the command post if needed for a real rescue.

- The teams felt frustrated because of an equipment shortage during the drill. This is true to life, as there often are equipment shortages during rescues. It also illustrates the importance of being self-contained units. It shows the need to carry’ as much equipment as possible, but of course you can’t carry every tool. The FEMA proposed equipment standards will address this problem.

- Some people complained that the command post was too noisy. Actually operations to fix the nearby gas leak caused the noise, but since you can’t predict where a gas leak will occur, you have to work around the noise problem. The command post was positioned to give command an overall view while keeping them out of the rescuers’ way.

IN RETROSPECT

We are now in the recovery phase of Rescue ’90. Once the students left, our job was only two-thirds over. We had three days to remove 120 dump truck loads of debris, find a place to dump them, and recondition the site.

Would we do it again? The experience was tremendous, the learning was great, but it took a lot out of the staff members. The impact on day-today life in the Montgomery County firehouse was noticeable. The Rockville Volunteer Fire Department, which houses the collapse rescue unit and many of the key seminar personnel, felt the greatest impact.

The event had a positive impact on the team and personnel who were actively involved in the conference. Normally we could never send 50 plus personnel to a conference. If we did they wouldn’t receive the contact and exposure that they did as a result of hosting Rescue ’90.

We hope that other jurisdictions will follow our lead and take on this “impossible task.” The urban rescue community needs to continue to exchange information in this quickly developing specialty. Training needs to be available to all interested parties. Increasing the availability of training will further enhance the program throughout the U.S. in preparation for the real “Big One.”