Wildfire’s Elite

FEATURES

MANAGEMENT

Editor’s note: This year’s wildfire activity in several Western states is being described as the worst ever. By the time late summer seared its way onto the calendar, more than 1,000 square miles of vegetation had turned to cinders. Smoke was so thick that breathing the air in Northern California was like smoking 3 1/2 packs of cigarettes a day. More than 20,000 firefighters went on this run; at least seven of them were killed.

The fires obliterated wildlands in large sections of California, Oregon, and Washington. According to the U.S. Forest Service and the California Department of Forestry, 9,500 people were evacuated, and 14,400 fires burned at once at the peak of activity. At times, hundreds of fires burned without response as personnel concentrated on more threatening blazes. Other problems were visibility and access.

These strategic challenges echo the conditions of the summer of 1970, reinforcing the lessons learned that year and applied to the fire management mechanism described here.

TX ry lightning. Even city and 1 suburban firefighters A-/ know the havoc it causes.

The perspective is different in our nation’s forests, where a single bolt of lightning can result in the devastation of thousands of acres of timber, watersheds, and game preserves.

In talking about dry lightning storms, Deputy Forest Supervisor Mike Edrington at the Willamette National Forest in Oregon repeats a single one-word description: “Awesome.”

That’s not the repetitive, trivial slang of teenagers. Satellite computers show it takes 100 to 150 such lightning strikes to start a single fire. During one awesome night in August 1986, lightning ignited 200 to 300 fires in an area of northeastern Oregon where weary firefighters were starting to gain control of more than 100 other fires that had started the same way a week or so earlier.

During the first two weeks of what was to be a month-long battle, dry lightning storms touched off more than 800 fires—more than two an hour— in the Pacific Northwest states.

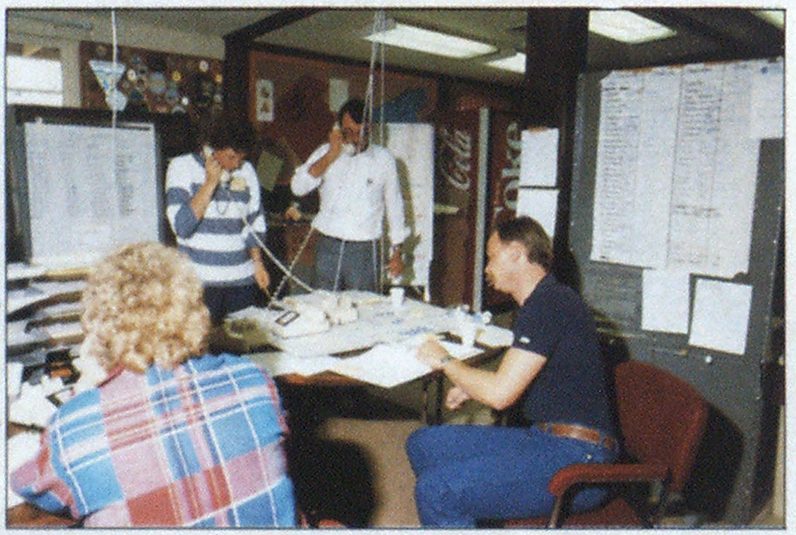

Photo by Jack A. Bennett

By the time they were extinguished, the flames had consumed more than 200,000 acres, an area slightly larger than Dallas, or all of New York City’s five boroughs combined. Forty-nine starts had grown rapidly into major fires of more than 1,000 acres each; the blazes destroyed millions of dollars’ worth of natural resources and man-made improvements.

Some 22,700 firefighters, including 695 crews of 20 members each, plus 398 engines, 112 water tenders, 73 helicopters, 76 bulldozers, and more than 30 air tankers were used to fight fires scattered over an area the size of South Carolina—20 million acres.

Today’s system for control of these firefighters and all their equipment is largely the result of lessons learned during a devastating series of fires during the summer of 1970, when 14 firefighters died, 870 homes were destroyed, and more than 700,000 acres of Western forest and rangeland went up in smoke. Long before those fires were out, commanders had already learned they had to share information about radio equipment and frequencies, in order to agree on standard terminology for pieces of equipment with different names in different jurisdictions.

That transition was neither swift nor easy, but the ability of most fire services and what are now known as national and regional fire teams to combat brush and woodland fires anywhere in the nation, including Alaska and Hawaii, is much better as a result. After several years of planning, the switch from the large fire command structure started in 1975. By the end of 1985, all federal wildfire the end of 1985, all federal wildfire agencies and most related state agencies were using today’s incident command system.

Members of the teams, known as Class I National and Class II Regional Fire Teams, are the elite, specially qualified by experience, then chosen for fire team training. The teams, fewer than 40 in all, consist of eight or nine firefighters each; training of potential replacements is conducted only once every two years. Working for the U.S. Forest Service, which administers the teams, Ken Dittmer supervises the instruction at the National Advanced Resource Technology Center outside Tucson in Marana, Ariz. The center provides advanced resident courses on a regular basis.

From applicants who must meet strict requirements, have considerable fire command and related experience, and come highly recommended, a steering committee of chief fire officers selects candidates for the Class I Advanced Incident Management Course. Only 72 are chosen, then organized as a dozen six-member teams.

Dittmer says the two weeks of grueling day and night exercises they experience “represent the highest level of training we can provide to incident manangement teams short of the real event.” Instructors watch and evaluate each team and each member carefully throughout the day, critiquing them at regular intervals. Members must learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses, then develop whatever techniques are necessary within the team to succeed as a unit. If they fail to do that, they fail as a team.

The curriculum includes Team Development, Team Organization, and Team Communications, courses designed to teach candidates more about the incident command structure they’ll operate within when they move into fire team status. They also learn Area Command Organization—the coordination of several teams operating within the same general geographical area on a common fire situation.

Incident Management Transition is instruction in how to assume command from the team or agency a fire team will replace; Escaped Fire Situation Analysis is the course in recognizing the existing and potential dangers, how to combat them, and how to prevent them from becoming worse. Demobilization is the instruction in turning command and control back over to other, subordinate fire service organizations once the fires are brought under control.

External Relations, Media Relations, and Urban Interface are the courses in which candidates learn the realities of dealing with the civilians and the politicians outside fire command.

Aviation is the course which crams into a few hours the basics of safety, administrative, and tactical procedures involved in contracting for and using the three types of aircraft: helicopters, fixedwing attack, and fixed-wing reconnaissance and command airplanes. As with every other facet of their instructions, candidates learn from experts acknowledged to be the best in their respective fields.

A course in the fiscal aspects of using all this equipment goes with the rest of the instruction.

National fire team members are also trained to work under almost any conditions, with special classes in strategies and tactics for the nation’s principal forest regions— Southern California, Alaska, the Rockies, the Pacific Northwest, Great Basin, the Northwest, the Southwest, and the Northeastern United States.

Near the end, the candidates face an all-day exercise which duplicates as realistically as possible the tasks they’ll face as fire team members. The simulation starts with a briefing at 6 in the morning, when the team is made responsible to take over an incident. During the exercise, these candidate teams experience the unexpected: A mayor may arrive at the fire command station to complain that homes in his tiny town are threatened, a rancher may face the loss of rangeland and hundreds of head of cattle, or perhaps the governor will demand a reconnaissance flight which could be extremely dangerous in the quickly shifting thermals over rugged terrain and the fire’s updrafts. The team must handle the incident, with all its complexities, and pass two other exams to complete the course successfully,

Rank has no privilege here, nor is immediate acceptance and assignment to a fire team guaranteed. Graduates’ names are placed on a qualified list; they face a separate selection process when one of the 17 Class I National Fire Teams has an opening. Mike Edrington says his criteria in selection are personal ability, dedication to the fire service, and a demonstration of synergy in a firefighter’s ability to work and get along with tire other members of the team.

Mk Meanwhile, graduKjf ates of the fire team training units from which they came, and continue to serve with them. Once chosen for a team, graduates are available on a five-week, two-off and three-on duty rotation. During the three weeks each fire team is on call, the restrictions on a member’s time grow increasingly severe. The first week, each fire team member must be ready to leave for a fire in any one of the 50 states on 24-hour notice; that drops to eight hours during the second week. The twohour notice condition imposed in the final week barely allows time to buy groceries; if a team member is already at a fire with that firefighter’s regular unit, the fire team call takes priority and the team member’s normal fire service organization sends a replacement to the field.

Fire team members receive no special pay; their regular units bear the cost of their salaries, even during their training in Marana.

The Class II Regional Fire Teams usually handle smaller fires, those less than several thousand acres, within their own and nearby states.

Like a varsity and junior varsity, the two classes of fire teams work separately roughly 99 percent of the time. But during the August 1986 seige in the Pacific Northwest, 15 of the 17 Class I and 18 of the Class II teams were working under the same unified area commands.

Flere’s how it happened:

By the final days of July 1986, Mike Edrington was already describing that summer’s drought as “prolonged.” When lightning started a number of fires in the northeastern quarter of Oregon, local fire agencies went after several dozen 200to 300-acre fires. A day or two later, lightning struck again, starting 100 to 150 more fires, all initially attacked by local fire units from the Oregon Department of Forestry, the federal Bureau of Land

Management, and the U.S. Forest Service. And although several Class II Regional Fire Teams were involved, firefighting operations by the three agencies were still largely independent.

When the winds started to pick up during the first days of August, small “sleeper” fires started spreading rapidly and the units already involved began to “fall behind the power curve”—they were in danger of losing control. Four Class I Teams were called to duty, three from Oregon, one from California. By the end of the week, three more were called for the stubborn problem area around Baker, Ore. The seven teams were trying to handle nine major fires of more than 1,000 acres each, and a couple of intermediate fires quickly headed to major fire status, triple to quadruple the teams’ normal work load.

By now, the need for area commands was superseded by the need for an even larger command, known as the Unified Area Command Authority.

Each Class I team has its own command structure, of course, with an incident commander and deputy, an operations section chief or two, a plans chief, logistics chief, air operations chief, finance chief, and safety officer.

But leaving each team with all of its own command and control responsibilities under the existing conditions would have failed. So one or more teams were assigned to a complex of several fires and charged with suppressing them and making the initial attack on new starts in their respective areas. Moving responsibility for overall strategy up to the UACA accomplished three important goals. It freed firefighters and teams to fight fires, it allowed overall commanders to look at their objectives and set priorities which met the needs of the fire agencies involved, and it permitted realistic decisions for the allocation of scarce resources.

The team’s three members, one from the Oregon Department of Forestry, one from the Bureau of Land Management, and Edrington from the U.S. Forest Service, got fast, excellent experience in sharing command equally as fires raged without any regard for jurisdictional responsibilities.

Within a week and a half, most of the fires were contained, and the UACA officers were preparing to debrief the Class 1 teams and start the process of sending them home.

Then a huge bank of cumulus clouds built up across the entire area, and in one night, a third series of dry lightning storms set 200 to 300 new fires around the Baker command center in Oregon and nearby sections of| Idaho, 50 miles away.

Suddenly, the 5,000 firefighters under the Baker UACA were not nearly enough; no one was going home.

During that morning’s fourhour reconnaissance flight, Edrington says, he was never out of sight of a new start in a 150-by-200mile area that now touched even into the southeastern tip of Washington.

Quickly, more Class 1 teams and management teams were ordered; on-location incident teams were sent to attack the new fires while local teams relieved them in areas where the fires were contained. Within two days, a second UACA was set up in the northern part of Oregon while Edrington and the others at Baker concentrated their efforts on the three large fires and dozens of smaller fires burning closer to their command center. A third UACA was set up near Pendleton, Ore., as 100 new fires, including some which escaped initial attacks, grew there. A fourth and final UACA at Boise, Idaho, more than 100 miles away, took control of the wildfires in that state.

By the end of August, the battles on all four fronts had been won. The largest single mobilization of firefighters and equipment in U.S. wildland fire history was over. The success w’as no accident. Learning from the killer fires of 1970 and refining command and techniques constantly since then, the UACAs operated on geographically defensible principles with effective, central staffs to coordinate planning and logistics. The joint command structure settled potential jurisdictional questions before they could become problems.

This spring, as they do every year, the incident commanders from all 17 teams met for three days to review and plan, and to learn about highly sophisticated equipment such as helicopters using infrared guidance controls for night flights, which are now available to help in their work.

Later in the year, each of the fire teams conducts a three-day meeting of all its members, reviews the incidents from the previous year, learns of policy and equipment changes, and meets any new replacement personnel chosen from the team at the incident commanders’ session earlier in the

Edrington explains why today’s system of wildland fire suppression is so aggressive. A hundred years ago, even a generation ago, the wildlands, timber, and watersheds were very sparsely settled. Even today, in areas without settlement and where the timber isn’t available for harvest, some fires are just monitored and allowed to burn. But throughout most areas, tiny towns, ranches, and valuable watersheds are likely to be just a ridge or two from where a fire starts.

Thanks to extensive training, ongoing instruction, and experience, forest supervisors and land management officers can take comfort in knowing wildland fire teams provide the United States with a highly efficient and cost-effective way to handle major incidents.

Working to make a burning state “Fire Safe, California!”

Although the wildfires that blanketed California this past summer may give a different impression, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDF) has a very effective fire prevention program, the department’s education officer believes. The problem, Jack Wiest says with an ironic laugh, is that “unfortunately, we don’t have a good rapport with God.”

With responsibility for protecting more than 30 million acres of forest, range, and watershed lands in the state, CDF has a $180 million fire protection budget, and $10 million of that goes to prevention.

With $200,000 a year and the help of a major advertising agency, CDF launched a two-year public information campaign in June. The honorary chairman of “Fire Safe, California!” is Ted Schackelford of the CBS series “Knots Landing.” He’ll tour the state and appear in public service announcements on radio and TV. The message also goes into print, in newspapers and the inflight magazines of United and PSA airlines.

A high-quality media kit brims l with information on CDF and wildfire in California, phone numbers of public informaH tion officers in each of the department’s stations, a glossary, and guidelines L ⅝ for reporters.

CDF addresses homeowners with pracinformation about installing spark arresters on chimneys; ensuring an adequate water supply; and maintaining a “defensible area” around houses by pruning tree branches, clearing away shrubbery, raking up dry leaves, and planting low-flammability ground cover. The department even goes so far as to advise prospective home buyers on how to choose fire-safe structures and communities.

Engineering and enforcement are also part of the prevention role. CDF sets standards for the clearance around railroad tracks to keep dry foliage away from the heat of train brakes; for fire safety features of utility lines; and for spark arresters on all internal combustion engines.

Although recent conditions have created added urgency, CDF has decades of fire prevention under its belt. A team-teaching effort for grade school children—in which some of the department’s 3,000 volunteers lend a hand—is better than a quarter of a century old. By tracking wildfires where education has and hasn’t been intense, CDF has concluded that its programs have reduced the incidence of child-caused fires by half over 15 years.

Children come in third on the list of most common fire causes in the areas under CDF’s protection. Arson is second, and equipment usage and debris burning tie for first at 20 percent each.

But Wiest points out that much of this year’s fire activity has been on land that’s under U.S. Forest Service control, in the state’s mountainous regions which are more susceptible to dry lightning storms. So whatever California foresters’ rapport with a higher being at the higher altitudes, Wiest can argue convincingly that CDF’s fire prevention record shows “we’re probably doing a better job as a department than we’ve ever done.”

Photo courtesy of the California Department of Forestry