Staying Off the Collision Course

features

APPARATUS

Safety on the road has two major elements—the apparatus and its driver.

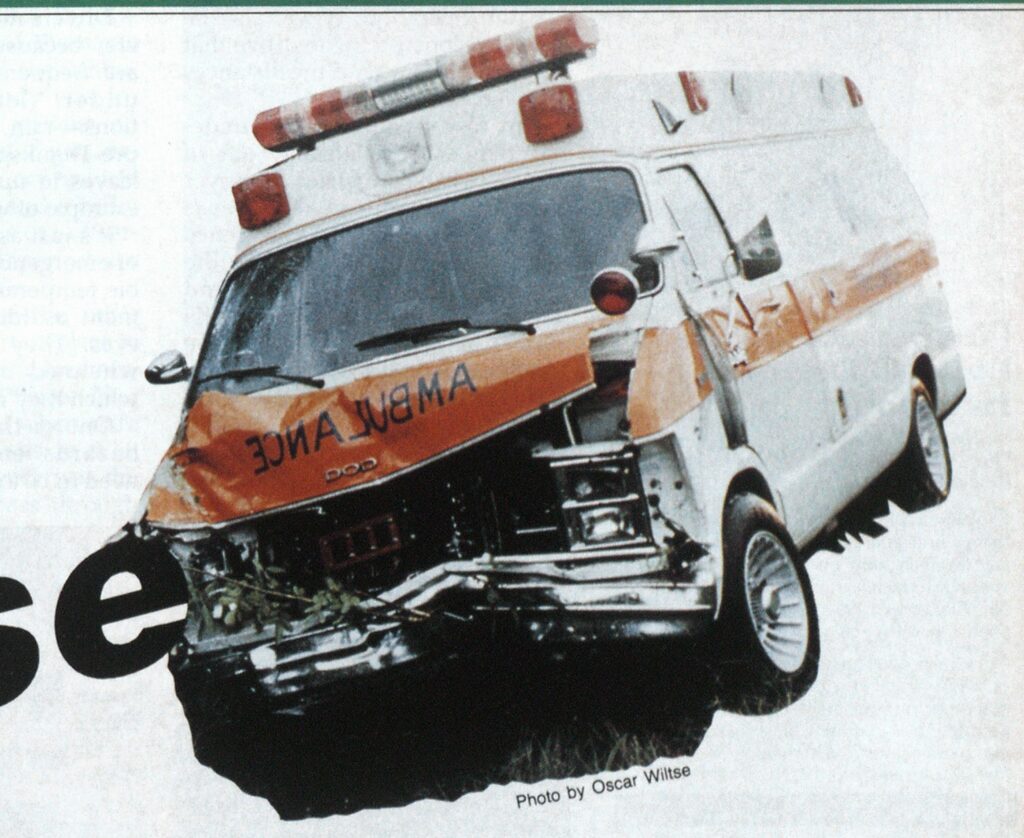

Wet leaves transformed an otherwise gentle curve into a dangerous driving situation for an upstate New York ambulance driver last fall. The vehicle left the road and mangled a guardrail before coming to a stop in someone’s front yard. Nobody was injured, but another unit had to be called to transport the patient, and a badly needed ambulance was out of service for six weeks.

When screeching brakes and the crash of metal involve an emergency vehicle, time, lives, and equipment can be lost. Crowded highways, poor road conditions, and inclement weather make an emergency vehicle driver’s job difficult, but we are still legally, morally, and financially responsible for our actions. Our responsibilites extend to the other drivers with whom we share the road, the crew riding with us, and the patients on board, to name just a few.

Photo by Oscar Wiltse

And the job becomes more difficult with the passage of time. The roads in most cities are becoming increasingly crowded: In the state of Florida, 125 new cars are added to the roadways each day. While our apparatus gets bigger, more powerful, and more valuable, our warning systems compete with louder stereo systems inside better insulated cars.

And with the number of emergency responses as high as it is, the public becomes more and more complacent in the presence of our air horns, sirens, and emergency lights. According to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, as many as 5,300 fire trucks were involved in accidents from 1983 to 1985.

Departments can undertake safety precautions in two main areas: apparatus and drivers.

The firefighting apparatus you put on the road must be properly engineered and designed, never converted from another type of vehicle. In Georgia recently, a fire truck responding to an alarm completely rolled over. The driver escaped with only cuts and bruises, but another fire apparatus had to be dispatched to extinguish the fire. The truck, never designed to be an emergency vehicle, was also severely overloaded.

But engineering and design are compromised if you don’t provide proper maintenance. A daily checksheet of each emergency vehicle in service should be completed as soon after each shift change as possible. This checklist should reflect the vehicle’s operating condition for that day. It should specifically indicate that all driving lights, emergency lights, sirens and horns, directional signals, brakes, emergency brakes, and steering were in proper order; and that all fluids, such as oil, brake fluid, and power steering fluid, were filled to proper levels.

The daily vehicle checksheets should be signed by and list the names of the crew members on duty for that vehicle each shift and indicate the date, time, and odometer reading. The checksheets should be on file for 30 days, unless the vehicle is involved in an accident. In that case, they should be considered legal documents that may be subject to a subpeona for a court proceeding. By holding onto the previous month’s checksheets for that vehicle, your agency will be able to demonstrate in court that it carried out a careful program of vehicle maintenance for safe operation. It will also be able to reconstruct who drove that vehicle each day, and the distances traveled each shift.

Any case in court—and your department’s ability to stay out of court—will be enhanced by driver training (drivers can only be as good as their training). Emergency driving should frequently be the subject of a department drill, and ‘ documentation of these drills should be kept. Should you have to appear in court in regard to an accident with an emergency vehicle, training records and a demonstration of a safety-conscious attitude would be to your advantage.

(Photo by Oscar Wiltse)

The people you put behind the wheel should be properly trained for the type of service in which they’re involved. For example, in training police officers for highspeed driving, the emphasis is on speed, pursuit, and rapid recovery from 360-degree spins. Obviously, an ambulance driver or the driver of a fire vehicle is going to try to drive more smoothly and will definitely need to avoid 360-degree spins. Training programs for the drivers of fire apparatus should emphasize skills such as backing with mirrors through a serpentine course and stopping large vehicles without skidding.

Any good training program for drivers of emergency vehicles should include a wetted skid pad. This allows the instructor to simulate rapidly changing road surface conditions and to prepare the student driver to handle miscalculations of the laws of physics.

Drivers must be weather-watchers, because emergency vehicles are frequently asked to respond under “letter-carrier” conditions—rain, snow, and sleet. That pre-Thanksgiving accident on wet leaves in upstate New York is an example of weather’s effects.

It’s just as important for drivers of emergency vehicles to have stable temperaments and good judgment as for them to have good eyes. They must never be overwhelmed by the emergency to which they’re en route.

One of the most unpredictable hazards emergency personnel need to be aware of is other motorists. Perhaps none is as dangerous as the drunk driver; assume that any motorist on the road between 11 p.m. and 5:30 a.m. is intoxicated, until proven otherwise.

But the other driver doesn’t have to be drunk to be confused. Although fire and rescue drivers are trained to act appropriately when responding to emergencies, they must remember that other drivers often don’t know what to do when they see flashing lights and hear sirens.

The confusion of other drivers requires apparatus drivers to be doubly cautious. At a major intersection in Savannah, Ga., an ambulance on an emergency response came to a full stop to fully assess the traffic—as dictated by department policy and good driving attitude. The driver of a large truck also entering the intersection, but from another direction, became confused by the ambulance’s full stop. Both the ambulance and the truck resumed travel at the same time; the truck struck the ambulance broadside. Nobody was injured (there was no patient on board), but the response was delayed, another emergency vehicle had to be dispatched, and a badly needed ambulance was out of service for an extended period for repairs.

Primarily because of the other driver, the most dangerous place to be is second in line during an emergency response. In Fort Pierce, Fla., a fatal accident occurred when a fire vehicle struck a car broadside at an intersection. The fire truck was the second apparatus to pass through that intersection in response to what turned out to be a false alarm. In New York State, two fire department ambulances were responding to an automobile accident. The driver of another vehicle apparently was distracted by the lights and sirens of the first ambulance; she entered the four-way intersection at the same time as the second ambulance and was struck broadside. The driver of the car and her passenger died of the injuries they sustained in the crash.

If you’re driving the second vehicle in an emergency response, be sure to leave an adequate interval between your vehicle and the first emergency vehicle. Another way to help motorists is to run a different siren mode in each unit; drivers should be able to recognize the different sounds and realize that another rescue vehicle is on the way even if it isn’t yet in view. And if a police officer offers to run interference ahead of you and provide an escort, refuse the offer. You have as many lights and sirens as the police car, and two vehicles responding doubles the risk of an accident.

Drivers of emergency vehicles in the fire service make decisions in split seconds that the courts can agonize over for years. It’s important to frequently raise our level of conciousness in regard to this. Our skills for operating emergency vehicles should be as finely tuned as our skills in pump operation, fire suppression, or patient care.