By Martin J. Rita

Despite the history and tradition in the fire service, modern fire dynamics are forcing us to seek ulterior tactics to improve firefighter safety to reduce injury and death. We train on fire behavior, reading smoke, ventilation, overhaul, search, ladders, preincident planning, and we even conduct commercial fire inspections. Why is it that we very rarely train after the conclusion of an incident? If you work for a fire department that conducts postincident critiques after “major” incidents, then I commend the leaders of your department. If you are one of these leaders, your progressive approach will tempt you to read ahead in hopes that new ideas and approaches will challenge you and your current program.

We have always heard the statement, “Firefighters are Type A personalities.” Before you gloat about your honorable traits, know that the traits of a Type A personality include hostility, impatience, difficulty expressing emotions, competitiveness, perfectionism, and an unhealthy dependence on external rewards. So, now with the brief understanding of our behaviors, it is presumably safe to understand why many of us do not conduct or participate in postincident critiques. As firefighters, we do not want to be “called out” in front of our peers, we do not want to be the subject of ridicule, and we sure don’t want to be the focus of policy or operational changes that could lead to professional embarrassment. Chiefs, company officers and senior guys: We MUST implement postincident critiques if your department currently does not participate in them, or we MUST make drastic changes to the method in which we currently conduct them.

The Value of a Postincident Critique

The United States Fire Administration has already provided valid examples of the value of postincident analysis. They follow:

- Critiques provide personnel with a clear indication of the impact their actions had on the outcome of the incident (good or bad).

- Discuss effective/ineffective strategies and tactics to be used. Identify errors so you can take immediate action to prevent reoccurrence. DO NOT PLACE BLAME.

- Discuss positive outcomes—even if they are minor—and reflect attention to good decision making, leadership, and hard work. It is detrimental to the new generation’s confidence to reward their positive efforts.

- Help to identify the need for remedial training for personnel. (Discuss your concerns with the Training Officer after the critique.)

- Allow for a discussion on flow paths, fire behavior, building construction, coordinated ventilation/fire attack, and critical lessons learned.

- Create a training environment that promotes trust and encourages your personnel to openly discuss their own successes and failures.

Establishing Policies and Procedures

Successful implementation of any program must first come from the leaders. Chief officers must create policies and procedures that hold their officers and firefighters accountable for their actions. Create a policy committee that includes firefighters, company officers and chief officers to allow positive feedback to funnel down to the rest of the department. Create a format of how your department would like to operate a postincident critique. It is absolutely paramount that chief officers, incident commanders (ICs), and safety and company officers participate in each postincident critique. This allows for the critique to remain on task, optimistic, and neutral to all firefighters operating at the scene. Remember, this is NOT the time to complain, to tell everyone how great you are, to tear down others’ performances and abilities, or to make jokes and reduce the importance of the critique. If you allow the foundation of a negative learning environment you will have a very difficult time achieving program success.

Who, When, Where and How???

If you are like many fire departments, whether volunteer, paid on call, part time or career, that have never implemented a postincident critique, here are the who, what, when, where and how of that implementation.

WHO?

The most effective way to run a postincident critique is to include every initial arriving company on scene in the discussion. Fire department operations vary across the country, so it is up to your department to determine who your initial companies are. In the south suburbs of Chicago, the initial “still” companies include neighboring (automatic/mutual aid) communities, so I would attempt to include them in my critique. A good rule of thumb is to include your still or “working fire” response crews (excluding any box-level companies) after a majority of the incident has been mitigated.

WHEN?

If possible, conduct the postincident critique within the first couple days of the incident and with as many of the personnel that were originally on scene as possible. If you wait any longer, you risk inconsistencies in tactics, rig placement, operations, and so on.

WHERE?

Conduct the postincident critique in a location that is conducive to learning, i.e., a comfortable setting (photo 1) that fits the adequate amount of invited personnel such as a department training room with a dry erase board, TV, computer, and so on. Also incorporate any live pictures from the incident as well as any preplan drawings, critique forms, or outlines created according to your policies and procedures.

(1) Photo and figures by author.

HOW?

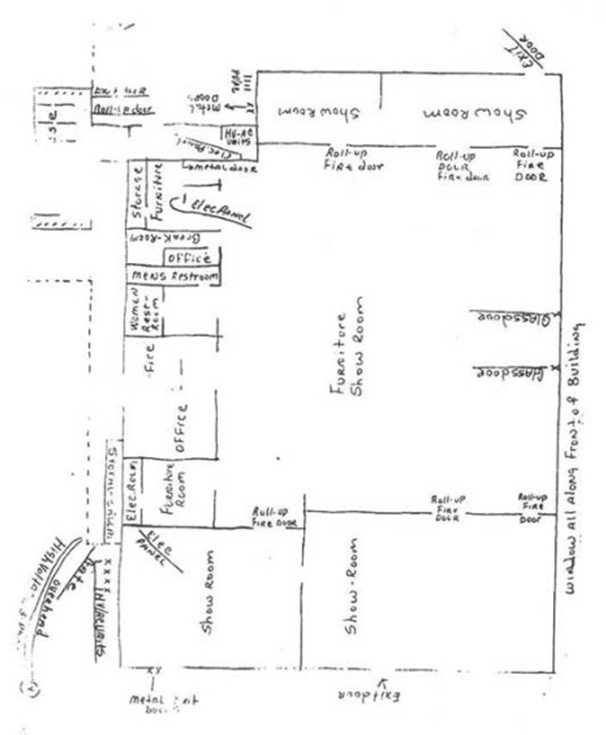

1. A Rough Drawing/Sketch of the Incident

Have one of your first-arriving personnel do a rough drawing or sketch of the incident (Figure 1). Have them include hallways, bedrooms, stairs, windows, and egress locations, if possible. This will help them visualize the scene, allowing for preincident knowledge such as line placement, seat of the fire, ventilation locations, crew locations, electric/gas meter location, and any other hazards that may be of interest.

Figure 1. Sketch of the Incident

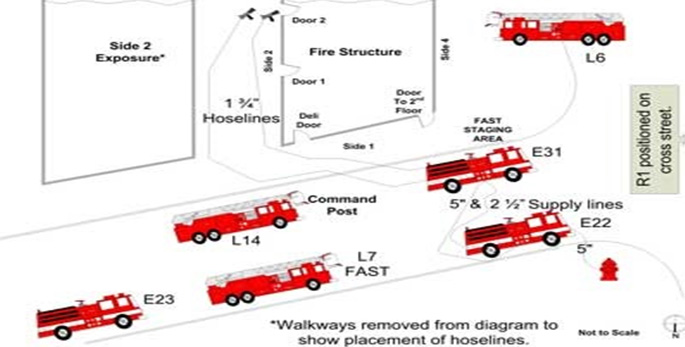

2. Computerized Diagram of the Incident

A legible and organized preplan is recommended if time allows, but it is not necessary for a critique to take place. There are additional educational opportunities when you can edit changes during that critique such as dry erase markers to show change in line placement, entrance/egress locations, moving companies, and so on (Figure 2). Have a decent number of personnel from the initial incident present to inform you of their tasks, locations, and objectives as you go through the critique, or else this preplan will not be beneficial.

Figure 2. Computerized Diagram

Document the location and size of interior/exterior attack lines, companies assigned to fire attack, ventilation, search, rapid intervention team, specialized equipment, victim locations (if any), fire department connection, ladder placement, and more. If you are documenting these actions, ask multiple times throughout the critique if you have the correct placement of hose and equipment. This portion of the critique is for fact finding only! Do NOT start discussions or make any interpretations or determinations until all the facts are gathered.

RELATED: Tracy on the Postincident Hotwash ‖ Reeder on the Postincident Evaluation Drill ‖ Viscuso on Writing Your Structure Fire Report Narrative

3. Drawing/Computerized Diagram of Exterior Operations

An exterior operation diagram (Figure 3) can indicate just as many important incident specifics as interior operations. These specifics include water supply locations, supply lines, exterior attack line positions, and apparatus placement and direction of travel for engines, ladders, trucks, squads, tenders, and/or command vehicles. It is also important to document the location of exposure buildings, alleys, and gangways.

4. Dispatch and Communications

In a critique, it always proves beneficial to obtain a copy of all recordings of dispatch and communication from the incident. This obviously depends on your jurisdiction and radio communication procedures, but you should always try to obtain copies of and information for the following:

- The 911 call and the operator taking the call. Discuss if there can be improvement in any dispatch procedures or delay in receiving the initial alarm.

- The “main” channel. This is main channel your department uses to document en route, on scene, and so on.

- The “Fireground” or ”Tactical” channel. This is a local channel used to communicate to companies working on an incident without tying up traffic on the main band and that filters out unnecessary radio traffic from other jurisdictions.

- The IFERN (Interagency Fire Emergency Radio Network) Channel. This channel is used for responding, staging, and assigning job tasks to companies responding to working fires (This is optional if the incident did not use it.)

5. Incident Task Analysis

Another integral part of a constructive critique is the ability for the “host” or “moderator” to stay completely objective and neutral for the duration of the training. Preferably, you should start with the first responding officer/shift commander. Allow each assigned “speaker” or representative of the company to speak in entirety, and document the findings. Encourage the company to provide updates on conditions and actions throughout the analysis; this will aid in the discussion regarding fire behavior and flow path and if there was any change of conditions possibly caused by the companies such as a delay in water to seat of fire or premature ventilation. Once you document all of the information, each company goes through their tasks, locations, and objectives; the interior/exterior preplan sheet is completed; and the radio communication is heard, it is time to have the companies grade each portion of the incident.

6. The Grading Scale

A grading scale is something I have recently implemented into postincident critiques to allow the initial company officers, shift commanders, or company representatives to voice their own opinions regarding the incident. This can encourage analytical thinking and promote professional development. In my previous experiences, firefighters do not want to be called out by their officers or judged their peers but, when given the opportunity, they are very critical on themselves. Emotions may run very high during this portion of the critique, so the individual running the critique, i.e., a critique/training officer, must maintain order and support the officers of the department. The grading scale categories should mainly be task oriented to promote continuing education, to set tactical goals and objectives, and to support the creation or revision of department policies and procedures. You may set up grades any way your jurisdiction intends as long as there is a scale that demonstrates the need for improvement or if it meets department standards. After you gather all of the information, encourage the groupto set an overall grade for each category. You can use the following as a guideline:

Dispatch Communications: A-F

- Problems with the initial alarm?

- Did the IC report routine updates to progress of the incident?

- Were there dispatch errors or needs for improvement (such as training or equipment issues)?

Apparatus Positioning: A-F

- Was apparatus positioned correctly? (Engine pull past house, three sides, and leave room for first truck, second engine back down, level 2 staging location, and so on.)

- If transition to defensive operation, was positioning effective or ineffective?

Initial Fire Suppression Companies: A-F

- Size-up of conditions on arrival?

- Line deployment (correct size line)?

- Declaration of offensive (name interior) or defensive operation?

- COORDINATED ATTACK with ventilation crew? (If no, why?)

- Delay in finding the seat of the fire?

- Conduct a 360° (rule out basement) and 360° follow-up report?

- Delegation of responsibility (i.e., Truck—assigned ventilation, second engine—water supply).

- Water supply issues? Communication to interior when on positive water?

- Safety issues, injuries, or equipment failures?

- Changes recommended to tactics, procedures, or training?

Ventilation Company: A-F

- Ladder placement (correct size and placement)?

- Second means of egress/ladder placement communicated to interior crews?

- COORDINATED ATTACK with engine crew? (If no, why?)

- Did ventilation occur before the initial fire attack? If so, did it have an effect on fire behavior or flow path or cause a change in strategy?

- Changes recommended to tactics, procedures, or training?

Interior Officer Communications: A-F

- Clear strategy of tasks, locations, and objectives communicated to the IC?

- Clear and concise communication to all sectors for the duration of the incident?

- Delay with initial fire attack and/or change of conditions communicated to the IC?

- Primary, secondary, or report of victims communicated to the IC?

- Transfer of command to the IC includes task, location, and objective of all initial companies on scene?

- Changes recommended to tactics, procedures, or training?

Search Company: A-F

- Clear strategy and communication of primary and secondary search of the building?

- Delay in search procedures for victims or any safety issues?

- Any changes recommended to tactics, procedures, or training?

IC Communications and Strategy: A-F

- Transfer of command? Conditions warrant increase of alarm?

- clear and concise communications to interior crews?

- Delegation of authority to sectors (i.e., operations officer, charlie officer, safety officer, and so on)?

- Accountability of all crews operating on the fireground for the duration of the incident?

- Implementation of RIT sector, rehabilitation sector, communication van, special MABAS equipment requests, and so on?

- Brief description of investigation, origin, and cause of the fire? Any problems?

- Provide a value and loss assessment of the building?

- Provide information of any civilian or firefighter injuries and a discussion of tactics that may or may not have contributed?

- Any changes recommended to tactics, procedures, or training? [VERY IMPORTANT]

7. Overall Incident Grade

Once you grade each category, it is time to provide an overall grade. Reassure all of your members that this grade only provides honest feedback as to what they need to improve on for future incidents; it is not meant to place blame or embarrass companies.

8. Discussion

Always conclude the critique with an open discussion of crews observations, tactical decisions, successes and failures (maintain positive comments only).

9. Conclusion of the Critique

The conclusion of the critique should not only include recommendations for additional training, possible changes in tactics and alterations, or additions of standard operating procedures but also acknowledgments of exceptional performance by crews and personnel. Recognizing sound tactics, good communication, and fundamentals will encourage others to perform well at the next incident. Do not discuss any errors in fundamentals or tactics; communicate these with the company’s training officer so your department can eventually conduct remedial training. If presented in an educated, regulated, and professional manner, the benefits of conducting postincident critiques will be crucial to the professional development and help eliminate mistakes on the fireground.

There is no better training than live incident training. We are doing the future of the fire service a disservice every time we do not incorporate a postincident critique. Always strive to increase the communication within your department.

Martin J. Rita has been a deputy chief/training officer for the Midlothian (IL) Fire Department since 2011. He has been an instructor for the Posen Fire Academy, a certified hazard zone blue card incident command training instructor, a MABAS division treasurer, a member of the MABAS training committee, and candidate/cadet program coordinator with a local Illinois high school. Rita has achieved a Bachelor’s Degree from Southern Illinois University and is working toward achieving chief fire officer certification, receiving National Fire Academy Certification, and a master’s degree in management.

Martin J. Rita has been a deputy chief/training officer for the Midlothian (IL) Fire Department since 2011. He has been an instructor for the Posen Fire Academy, a certified hazard zone blue card incident command training instructor, a MABAS division treasurer, a member of the MABAS training committee, and candidate/cadet program coordinator with a local Illinois high school. Rita has achieved a Bachelor’s Degree from Southern Illinois University and is working toward achieving chief fire officer certification, receiving National Fire Academy Certification, and a master’s degree in management.