From Drill to Real in 15 Days

TRAINING

It was midsummer last year when fire erupted at the Chevron USA Inc. tank farm near Philadelphia’s International Airport. But by a fortunate coincidence, personnel in a number of firehouses surrounding the area had been boning up on refinery fires of all types since early spring. Without knowing any details, they’d been told to prepare for a training exercise at Chevron’s drill area—an exercise that, as it turned out, occurred just 15 days before the real thing happened across the Schuylkill River.

We set it up to get some practice in standard operating procedures that had seen numerous changes since a fire at the same bulk oil storage facility—then owned by Gulf Oil Corp.—had killed eight firefighters in 1975. The major change was the naming of a plant coordinator to provide technical assistance to the incident commander. In addition, Chevron’s fire brigade now had a direct radio link with the fire department.

Over four months, hundreds of hours of work were put into the drill by the plant coordinator, the official in charge of plant security, the refinery’s fire chief, and four fire department officers.

To make full use of the live fire capabilities of Chevron’s drill area, we quickly agreed to have the drill simulate a complex incident posing an array of problems. Because most of the city’s refineries are near International Airport, we would begin the incident with a small plane developing engine problems as it approached the airport, causing it to crash into the refinery. This would trigger a chain of events that would include explosions, fires, a hazardous-material release, and injuries.

The plane itself (an old, singleengine model procured by the fire department) would be on fire, along with a tank simulated to contain 75,000 barrels of crude oil. A third fire—of pressurized, simulated hydrogen sulfide—was placed in a ruptured pipeline at the base of the tank. (Chevron employees built extra piping in the drill area to make this possible.) All three fires would be ignited shortly before the first companies arrived.

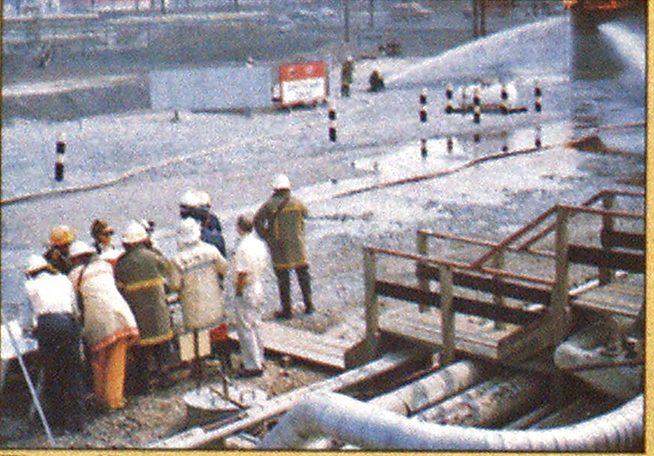

(Photos by John Skarbek)

A one-ton cylinder of chlorine was placed near the oil tank that was indicated as the fire problem, and the cylinder was designated as leaking. Casualties would include two people dead in the airplane and 12 injured on the ground. The dead were represented by training dummies; the injured were played by refinery workers and city firefighters.

The firstand second-alarm assignments for the refineries in the area consist of a deputy chief, four battalion chiefs, nine engine companies, four ladder companies, a fire boat, and a haz-mat task force. But because these are the firefighters who normally tour the plant every three months, about half of them were replaced with companies and officers from farther away. This, too, simulates reality, since the best preincident plans can go awry if the normal first-alarm response is in service on another working fire when an actual emergency occurs.

For the drill, extra pumpers, ladders, and battalion chiefs were assigned, as well as foam pumpers, a crash/fire rescue truck from the airport, a marine unit, chemical trucks, an air compressor unit, a communications van, two rescue squads, and a paramedic supervisor. This response brought together more than 90 city firefighters, in addition to 12 members of the plant’s fire brigade.

Covering companies were designated in advance and arrived at the participants’ stations before the drill began.

After the alarm was transmitted at 10 o’clock that Saturday morning, the first-arriving chief immediately requested additional alarms. The first companies on the scene donned self-contained breathing apparatus to protect against the haz mats, then rescued the injured. The commanding officers set up a command post and coordinated with Chevron officials. Simultaneously, they set up a triage area and arranged for the injured to go through decontamination procedures, then be transported to area hospitals. Staging areas were established for personnel and apparatus. Cooling lines were directed on the sides of the tanks and dispersion lines on the chlorine leak.

Nationally established formulas were used to figure the amount of foam needed to fight the tank fires, ensuring that enough foam was on hand before the initial attack began. After firefighters extinguished the tank fire and cooled the tank, a haz-mat team approached the chlorine leak and capped the cylinder.

Where the ruptured pipeline was on fire, crews used mobile handlines to drive it back, enabling a firefighter to close a valve and shut down the flow of hydrogen sulfide (simulated by propane).

The entire operation was conducted in an hour and 25 minutes.

In the following weeks, two critiques were held. The first was limited to the fire department officers and monitors who had taken part in the drill. The second also included the Chevron officials and officials from the outside agencies that had taken part: city police; city health, air management, and water departments; the city medical examiner; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Coast Guard.

There were lessons learned and reinforced about both fighting refinery fires and conducting drills:

- The goals and objectives must be set before planning begins. We had a whole list of things to accomplish, from strengthening interaction among agencies to observing how firefighters without experience in refinery fires would react.

- Participants had three months’ notice, but because they knew none of the details, they were forced to study up on all of the possibilities.

- This was probably the smoothest exercise we had run. But we knew from previous drills—delayed by multiple-alarm, real fires and other emergencies—to allow plenty of time between the initial planning meeting and the drill.

- Participating in a drill can be a stressful matter—your peers are monitoring your every move and decision. Planners, monitors, and participants should be rotated from drill to drill. And there are no negatives in a drill; mistakes should be looked upon as lessons learned or opportunities to reevaluate the preincident plan.

- As expected, the intermingling of outlying companies had allowed newer firefighters and officers who had never been engaged in battling a refinery fire to gain valuable knowledge. Those more experienced in such fires had a chance to review their knowledge and procedures. The exercise also enabled the fire department to review its triage procedures and incident command structure.

- Especially valuable was the fact that the drill introduced, in some cases for the first time, city firefighters, fire brigade members, Chevron technical personnel, and officials from outside agencies who, it turned out, would be working together under even greater pressure in two weeks.

Except for the handling of mass casualties and haz mats, all of the skills used at the drill would come into play again 15 days later.