Paradise (Almost) Lost

FEATURES

FIRE REPORT

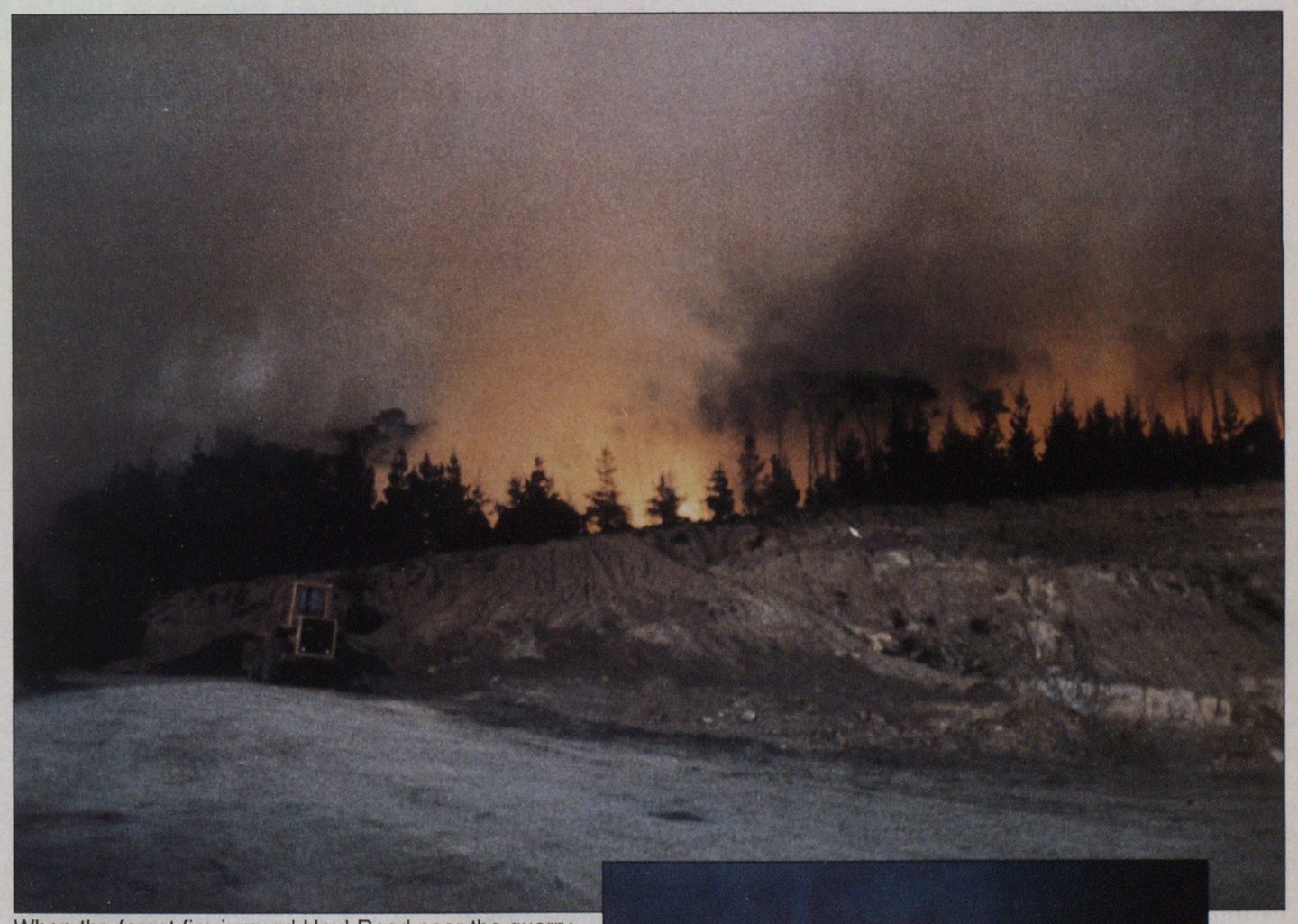

An urban interface fire in Pebble Beach, Calif., destroyed 31 homes, threatened firefighters’ lives—and taught hard lessons.

Power to their lift station pumps gone, their 5-inch supply hose cut, firefighters took refuge under their own apparatus as flames shot uphill out of three densely wooded canyons, across a firebreak, and over their heads. It ignited a dozen homes along a street in one of the most expensive, exclusive communities at the north end of California’s Big Sur coastline.

Perhaps 200yards away, Pebble Beach’s 800,000-gallon water supply tank stood untapped, and unavailable.

For much of the nation, the words Pebble Beach conjure up images of championship golf courses groomed to lush splendor in settings where the worst hazard is a two-stroke penalty after a misplaced shot falls to the rocks or into the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Pebble Beach is a small, private community of some 300 homes clustered near the top of 800-foot Huckleberry Hill overlooking Monterey and Pacific Garden to the east and north, and Mayor Clint Eastwood’s Carmel-by-theSea to the south.

The land runs from the sea upward to heavily wooded areas where the forest meets those more densely populated communities. Within Pebble Beach itself, most owners sought to maintain the rural attractiveness by allowing brush growing beneath the tall Monterey pines to remain unchecked and uncut. Trees downed by winter storms lay where they fell, unless they restricted travel along the narrow, winding, asphalt roadways with no curbs, gutters, or sidewalks.

On May 31, 1987, the Sunday afternoon weather was close to ideal: temperatures between 65 and 70 at the ocean, and 70 to 80 inland, relative humidity in the 50 to 60 percent range, and northwest breezes of 10 mph or more.

But in the forest and botanical preserve on the west-facing coastal slopes and canyons below the homes, the vegetation was dry. After three years of below-normal rainfall, rainfall during the early months of 1987 was running 50 to 60 percent below normal. The mature stand of Monterey pines, many of them 80 to 100 feet tall, and including a. couple of rare species, was overstocked, The slopes, especially in the DelMonte Forest and the Samuel F.B. Morse Botanical Reserve, were also crowded with Gowen cypress, Bishop pines, and coast live oak; closer to the ground, blue blossom, manzanita, huckleberry, coyote bush, and other shrubs competed with tall Pampa grass for sunlight and nourishment.

Nourishment was available in abundance, even if water had not been for several years. The partially decayed organic material on the forest floor known as “duff” was estimated to have weighed as much as 50 tons an acre, having accumulated virtually undisturbed for more than two decades. Another 26 tons per acre of dead vegetation was still standing among the 12 tons of live brush which was surviving despite the lack of rain. No one has estimated the amount of fuel available in the standing trees.

(above, photo by Steve Hart),

(right, photo by Joseph Pastore).

Because of the drier-than-normal winter, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDF) had declared fire season open May 4th, several weeks earlier than usual.

The quiet serenity of that sunny afternoon on the last day in May was interrupted when a local resident called Pebble Beach Security with a report of smoke. At 3:35 p.m., security notified the Pebble Beach Fire Station, CDF’s closest emergency command center.

Two engines were dispatched, one a four-wheel-drive vehicle known as a squad, carrying two firefighters and about 90 gallons of water, the other a pumper designed for structure fires, carrying three firefighters and 500 gallons of water.

The emergency command center had no reason to respond with more equipment to a simple report of smoke. According to CDF Captain Mike Marlow, who was first to arrive at the scene aboard the fourwheel-drive vehicle, fire season around Pebble Beach usually means 6 to 10 wildland fires a year, most of them contained before they reach 50 yards in diameter. Newspaper records indicate the most recent major fire, which burned 62 acres, had occurred 28 years earlier.

The engine, not equipped for off-road work, was parked at the edge of the pavement, its three firefighters then riding along as the squad pushed through the underbrush toward the heel of the fire 300 yards away. The brush was so thick, the firefighters had to walk in the final 30 to 50 yards.

“By the time we drove up there, the wind started to pick up,” Marlow says. “We squirted our water, which did nothing to stop the flames, realized the five of us with our hand tools couldn’t stop it, so we decided to regroup. As we were pulling out, a 500-gallon brush-type engine was arriving ahead of the head of the fire, 400 to 500 yards away.”

Within the first 20 minutes, the fire had involved one quarter to one half acre of heavy timber— duff, brush, and aerial fuel.

Incident command

Battalion Chief Bob Townsend, from CDF’s Pebble Beach station, assumed the role of incident commander and ordered two hand crews of 15 firefighters each to respond. The fire was already larger than most of the fires in Pebble Beach during the past three decades.

Seven minutes later, when Chief Townsend ordered two additional engines, the fire had doubled in size. The original strategy, to confine the fire near its point of origin, was already obsolete.

At 4:10 p.m., when Chief Townsend attempted to order the nearest air tanker from Hollister, only 10 or 15 minutes away, he was advised it was already committed to another incident and couldn’t be diverted. More than 200 miles and an hour away, Chico’s air tanker was available and promptly dispatched. Two more hand crews were ordered to respond; less than five minutes later, Townsend had also ordered a bulldozer for the position on Haul Road and a helicopter with a water-dropping bucket.

Fifty-one minutes after the first report came in, Townsend had cause for both confidence and concern, reporting that he was “beginning to get some control effort on the bottom end of this [below Haul Road to the west], but it is still moving at will with a strong wind.”

Thirteen minutes later, a spot fire was reported near the residences along Los Altos Drive; another firebrand was carried over the top of the hill hundreds of yards to fall near a structure on the Monterey side of Highway 68.

The first hand crews arrived at the head of the fire just before the first two spot fires were reported on the high side of Haul Road, 200 feet up a slope estimated at 56 percent in the direction of the fire.

Handlines were laid, but to little effect. Though the four engines gathered at that location had been carrying a total of about 2,000 gallons, most of that supply was already gone.

Calling in help

As the two spot fires grew together at 4:45 p.m., the original fire swept up to Haul Road, then across. The first-arriving crews had attempted to set a backfire, but it never had a chance to do its work; in little more than an hour, the blaze had grown to about 20 acres.

One hour and seven minutes after the first alarm, Chief Townsend requested Monterey County mutual aid: two response teams of three engines each. Fires were burning only several hundred feet from more than 40 Pebble Beach homes located just below the western crest of the hill.

Townsend also requested a command officer to take charge of defending the homes. Pacific Grove Fire Chief Charles Wilkins responded with the first mutual aid team, reported to the incident commander, then went to establish his sector command post at the intersection of Los Altos Drive and Costanilla Way.

What he found was confusion.

Four, not six, engines had been called because the dispatcher had mistakenly used an outdated draft of the schedule bv which teams were to be called. Three of the engines which had arrived were already committed with their hose lines laid; two engines had 5-inch supply lines connected to hydrants. Thirteen minutes later, dispatch got the correct pattern—but not before an extra engine had been sent and recalled.

The first CDF engine dispatched was now on Los Altos with another CDF structure-type engine and had successfully doused a couple of small spot fires.

But Chief Wilkins had other problems. With the fire now obviously moving up the hill, the local fire departments’ engines were preparing to put out the closest spots downhill and defend the homes uphill from six basically fixed positions. And Wilkins couldn’t easily determine what apparatus he had available, because not all of the responding units had been given the location of the staging area and command post, and the map being used showed inaccurate coordinates.

Concerned but not yet especially alarmed by the arrival of fire engines, nearby residents started using garden hoses to wet down the roofs of their homes, as well as the adjoining decks.

(Fire photos by Joseph Pastore; aftermath photos by Tom Welle)

Meanwhile, Chief Townsend had ordered two more water-dropping helicopters to respond; he also asked for water tenders to shuttle water to the engines still trying to fight the blaze from the bottom of the slope’s steep portion at the east edge of Haul Road. Although the fire was moving steadily uphill, the flames were now starting to fan out quite a bit along the flanks as well. The tenders carried between 2,000 and 3,000 gallons each; with a combined capacity of about 1,400 gallons, the four engines and one minipumper could keep the tenders busy. As it turned out, only one arrived before 7 in the evening.

Firebrands in the wind

Near the top of the hill along Los Altos Drive, the winds were now gusting to 30 miles an hour when the final engine from the first mutual aid dispatch arrived at 5:18 p.m. As glowing firebrands dropped into the layer of tinder-dry pine needles covering many of the roofs, firefighters did what they could to extinguish the spots before they spread.

At 5:21, Monterey County dispatch called the California Department of Forestry to ask about evacuating the residential area; concerned citizens were calling to ask for information. County Emergency Coordinator Art McDole says dispatch was advised there were no plans to evacuate at that time.

In addition to the six engines along Los Altos, Townsend had five other engines, one helicopter, one fixed-wing air tanker, and two hand crews on the scene—about 56 people in all. Four additional hand crews, one bulldozer, two helicopters, and another air tanker were en route; two more air tankers had been ordered, but for the moment, their availability was not confirmed.

Again, Townsend sounded a note of what might be described as cautious optimism: “We’re just beginning to make some good control effort. … I think that we will make more progress now that we can get more water on it. . . . Also, the structural threat has been abated. . . . That seems well in hand for the moment.”

For nearly half an hour, until 6 p.m., Townsend’s optimism appeared justified. Then a fire was reported in the backyard of a house on Los Altos Drive toward Sunset Lane, putting Wilkins’s sector command post almost directly between the burning home and the 50-acre forest fire on his other side.

A changed atmosphere

By 6:16, the atmosphere of the fire had changed. Smoke so dense that it obscured the sun was now down to ground level, irritating the firefighters’ eyes and impairing their breathing. Most donned selfcontained breathing apparatus in an effort to hold the line at Los Altos.

They couldn’t see what the air attack crews could from overhead: a significant increase in spotting, and uncontrolled spread as Wilkins was forced to pull his command post back to Costanilla Way and Sunridge Road.

The House Fires that Went Unprevented

(Photo by Steve Hart)

When the Pebble Beach, Calif., fire storm sw /ept out of the terrain’s cf limneys across Los Altos L )rive to the crest of Hucl deberry Hill, the blaze’s e ssential character remained that of a wildland fire bee ause so few of the homes had been separated even mi nimally from their environr nent.

Of the 31 homes totally destroyed, only 4 had been in compliant :e with PRC 4291, the state law requiring vegetation to be cleared at least 30 feet from buildings in wildland areas. In the 35 years since many of the early homes were built, the Monterey pines had grown to heights 60 feet or more above most rooftops, dropping more and more needles onto the ground and roofs alike; on many roofs, the tinder lay three inches or more thick.

Twenty-six of the homes had shake or wood shingle roofs; 25 had only single-pane windows, which allowed the heat from the tire to penetrate the home, imploding windows as the flames were literally sucked into the structures.

The assessment team evaluating the damage noted that no structure with a combination of PRC 4291 compliance, composition roofing, double-pane windows, and well-tended, nonnative landscaping was lost. Indeed, the house located on Los Altos Drive almost directly at the top of the chimney on the northwest side of Huckleberry Hill suffered virtually no damage excc ?pt to a small deck; in addit: ion to the other attributes, it was built with no over hanging eaves,

Durir ig the month of May, th le fire service had sent ne vs releases to local newspaj aers detailing the requiren aents of the laws regardi ng clearances around structures in wildland arei as. The interagency assessm ent team reports appear to indicate that no one acted to clear undergrowth or dead vegetation surrounding any home as a result of the printed reminders.

Good roads, good access, and a continuous water supply, none of which was available, CDF Battalion Chief Bob Townsend noted, would certainly have helped, but even they would not have been enough.

“Without fire-safe construction features built in,” Townsend says, “no fire department has a chance” in a situation such as the one at the top of Huckleberry Hill.

At 6:38, a structure fire was reported across from the El Bosque Drive cul-de-sac almost exactly at the top of the hill and a block away from Los Altos.

With what was to happen during the next 20 minutes, the first three hours would seem almost calm by comparison.

A bulldozer working on one flank from Haul Road requested a water drop ASAP. Another structure fire, this one on Sunridge Road about 50 yards from Wilkins’s sector command post, was reported at 6:41, as Townsend was requesting a mutual-aid strike team of five engines from local fire departments. They were dispatched to Wilkins’s original location. Some members of the strike team got separated en route; others didn’t check in at the sector’s staging area, in part because they couldn’t read street signs which were nonreflective and were attached to small wooden posts.

At 6:47, the residential area was ordered evacuated. Some residents had already chosen to leave on their own; others were still attempting to protect their homes with garden hoses. Within the next three minutes, a roof fire was reported on Los Altos near the backyard fire, and a less serious fence fire was reported on Sunset Lane, a block away at the top of the ridge. Fire personnel still fighting to hold their positions on Los Altos now reported winds gusting from 35 to 45 mph.

Blowtorch

At 6:52, operations at what was now known as the Morse fire for its proximity to the botanical gardens ordered five more strike teams—25 engines from the California Office of Emergency Services.

The new units were being assigned to Chief Wilkins, but by then it was really too late. The fire advancing uphill from Haul Road had funneled into formations known as chimneys, canyons formed by sides of adjacent hills, preheating the fuel in front of it so that the head of the fire moved with the intensity of a blowtorch. Spotting continued to be a problem, especially when firebrands carried over the crest of the hill and down toward Costado Road.

At approximately 6:49, workers from Pacific Gas and Electric followed standard procedure after receiving information that a structure was on fire in the area: They cut the power to minimize the danger from energized electric lines to both firefighters and the remaining residents.

With the power off, the pumps for the water tanks of the California American Water Co., an 800,000-gallon storage tank and a 10,000-gallon pressurized tank, were useless. With engines and residents using water almost as fast as they could, the report at 6:59 that the hydrants at the top of El Bosque “are a little low” amounted to a substantial understatement.

Refuge and retreat

As the hoses collapsed, Monterey City Fire Captain Ray LaFontaine cut the 5-inch supply hose and handlines with a fire axe so the engine and personnel could leave. Several of the units pumped their booster tanks dry protecting themselves and attempting to protect structures as a fire storm swept over Los Altos, touching off fires throughout the residential area along Los Altos, El Bosque, Sunset, and Costado Place and Road.

Wilkins ordered everyone out, but not everyone was able to get out: Firefighters caught between the chimneys without water had no choice but to take refuge under their own apparatus. The fire storm lasted less than five minutes, Wilkins estimates; but during that time, the heat was so intense that the filter burned out of the air cleaner in one of the brush-type engines.

As the fire storm subsided, Wilkins ordered all of the engine companies under his command back to the area to attack houses which it appeared could be spared. Morse Operations was trying to get the water company to turn on its booster pumps, and ordering 10 water tenders to supply the Los Altos engines as the firefighters— at least half, perhaps three quarters, of them volunteers—went back to work.

Generally built during the late 1940s and early 1950s, most of the homes had wood siding and wood shake shingles, the roof material the architectural review committee preferred in those days. Many of them, preheated by the blasts of flame leaping Los Altos from the chimneys, literally exploded inti flame. For them, Marlow says “we could have had an engine oi every house, and it wouldn’t have mattered.”

Lessons Learned

Communities should practice their mutual aid plans with live drills at least annually, and at some level quarterly.

Every firefighter, not just command personnel, must be familiar with the mutual aid plan to ensure its success.

Draft copies of mutual aid plans outdated by revisions should be collected, then destroyed or filed, to avoid confusion.

All fire departments involved in a mutual aid plan should have compatible radios; all apparatus dispatched for mutual aid should have a radio with at least eight channels.

Incident commanders requesting mutal aid should advise the communications center what radio frequencies are to be used, the location of the staging area, and to whom to report. Responding resources should acknowledge receipt of the information.

Check-in procedures should be standardized; mutual aid units should stay together from staging, or even from a prior rendezvous for the team, to release.

Proper radio protocols and language should be used.

Only resources requested by the incident commander should respond. While the impulse to do something to help is strong, self-dispatching should not be allowed. Agencies willing to commit additional resources should contact the communications center by telephone.

Each mutual aid response should be critiqued, to reaffirm the plan’s strengths and to correct its weaknesses.

Mutual Aid Static

The Morse fire at Pebble Beach was the first full-scale test of the Monterey County Mutual Aid Plan, even though the plan was written and adopted almost five years earlier. The plan covers 36 agencies.

When the Monterey County Mutual Aid Plan was written in 1982, the California Office of Emergency Services’ “white frequency,” 154.280 Mhz, was designated as the priority frequency for communications by units engaged in firefighting under the mutual aid plan.

On May 31, 1987, when the Morse fire started in Pebble Beach, the Monterey County commissioners hadn’t approved the estimated $6,000 to $10,000 expenditure for the equipment.

A year later, the expenditure still had not been approved. Monterey County’s fire departments are still using frequencies incompatible with the OES and CDF to dispatch in mutual aid incidents.

In addition, the CDF and Monterey County were supposed to use clear text; but in many cases, responding units from local fire departments used the codes they normally use when incidents don’t require mutual aid.

“Some of the houses were bound to burn, no matter what ap paratus we had available,” Town send agrees. Others have suggest ed that elsewhere, especially in the hills and canyons around Los An geles, houses would have beer “written off,” allowed to burn.

“The homes either burned to the ground or were spared with mino damage,” Townsend says. “Wt had no choice but to let the ones which were fully involved go.’ Even though all of the water had tco come from the tenders, Wilkins es timates most of the structural fires were under control by 9:30 p.m.

Control

With the exception of three or four small spot fires, the spread o the fire from house to house was halted by 11 p.m. During the pre vious four hours, the number o firefighters had grown from abou 100 to 885, structure-type engines from 13 to 38, brush-type engine: from 3 to 54, hand crews from 4 tc 27, helicopters from 2 to 7, wate: tenders from 1 to a dozen, com mand personnel from 6 to 72.

One hundred sixty acres and 3] homes were totally destroyed; other houses suffered some dam age, primarily to the roofs; 11 auto mobiles were destroyed, as were the trailer and microwave towe: belonging to a local cable TV operation.

Remarkably, no one—civilian OJ firefighter—suffered a seriou: injury.

At 6 p.m. the following day June 1, containment was reported mop-up operations continued foi another 2½ days until full contro was declared at 8 a.m. June 4.

Now, a year later, Montere) County’s various fire department and California agencies are stil taking action to implement the changes perceived as necessary, lessons learned after the tranquil ity and sense of security in Pebble Beach were shattered and almosi lost.