By Thomas N. Warren

In most parts of the country, we find a range of building construction of various age, from the very old to the very new. As an incident commander or first-in fire officer, identifying the construction type and age of a building will have a great impact on your tactics and strategy for operating on the fireground.

There are five types of building construction found in the United States:

Type 1—Fire Resistive

Type 2—Non-Combustible

Type 3—Ordinary

Type 4—Heavy Timber

Type 5—Frame

Residential buildings of one- or two-family construction are very common and are usually found in Type 3 and Type 5 construction. Multiple family dwellings of three or more family construction are also common in most urban and suburban areas. This is the area we will focus on, as most fire deaths occur in these types of residential structures.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) reports that in 2014 there were 3,275 civilian fire deaths in the United States. The NFPA reports that residential fires caused 2,745 (84%) of those civilian fire deaths, and also reports that in 2014 the leading cause of firefighter deaths was overexertion, stress and medical issues, as has been the case for the last several years. However, two firefighters were killed in structure fires when they were caught in rapid fire growth conditions in structure fires (1). As we move into the future, we will continue to see more residential buildings construction, and the vast majority of these buildings will be built using lightweight building construction methods and materials.

Simply put, most firefighting activity for today’s firefighters occurs in residential structures, and the most likely place for civilian fire deaths to occur is in these residential structures. The next factor to consider is that when firefighters enter residential structures to engage in an aggressive fire attack, they are placing themselves at great risk and need to consider the building’s construction and the fire’s advancement before committing to a prolonged aggressive interior attack. The manner in which buildings are constructed has a direct connection to the building’s ability to hold together while an aggressive interior attack is underway.

A few decades ago, firefighters would use the “20-minute rule” as a guide for interior operations. The rule simply assumed that a building of ordinary construction would stay structurally sound for 20 minutes or slightly longer when exposed to an out-of-control fire on two or more floors. Beyond this 20-minute point, structural collapse could be expected. This rule of thumb may have worked for our fathers and grandfathers, but can be a deadly guideline when applied to lightweight building construction today.

Lightweight building construction has been employed in building construction for the last half-century or more. The first multiple line-of-duty death incident related to lightweight building construction occurred in Wichita, Kansas, on November 21, 1968, at the Yingling Chevrolet dealership. Four firefighters were killed when a bowstring truss roof failed six minutes after the arrival of the fire department (2). It is fair to say that the dangers of lightweight building construction were not fully understood in 1968 by either the building construction industry or the fire service. Since that incident, we have learned and experienced a great deal concerning lightweight construction.

The concept of lightweight building construction was born of economic needs–a quick and less-expensive way was needed to construct buildings. The idea was simply to build strength into buildings through engineering rather than through mass. This revolutionary concept would allow builders to construct buildings with the same strength but with a much lower cost. The use of less wood and of smaller dimensions was developed to achieve that same structural strength as larger timbers fastened together. This is accomplished through the use of 2 x 4s that are actually 1 ½ x 3, plywood I beams, OSB (oriented strand board), gusset plates, roof/floor truss assemblies, wood adhesives/glue, and vinyl siding.

Combining these lighter building materials with architectural engineering was successful and produced the lower costs and strength that was envisioned, but an unexpected consequence came to light over time. This new building construction concept created several problems for firefighters. Constructing buildings using lightweight methods and materials created dangerously weak components when exposed to fire. It also entailed rapid fire spread in the large void spaces, rapid loss of structural integrity, and an increased toxicity in the smoke when the building components are burning. We learned that newer buildings of lightweight construction fail much quicker than the older buildings constructed of balloon frame or traditional legacy construction, and that fires in these structures generate much higher temperatures with extremely toxic smoke. The 20-minute rule our elders used is no longer relevant in today’s firefighting operations.

RELATED

Avoid Tactical Breakdown: Respect Lightweight Construction

Lightweight Residential Construction : Collaboration Adds to Firefighter Safety

Lightweight construction: misleading description?

USFA releases Web-based course on lightweight construction

So the question is: How can we quickly identify lightweight constructed buildings from older traditional constructed buildings? When we are responding to a building fire, what can we look for that will tip us off as to how a building was constructed? Quickly identifying how a building was built will have a direct effect on how our fireground operations will take shape. This is equally true for engine companies, ladder companies, and the incident commander. We must also be mindful that mixed construction (construction consisting of both lightweight and older traditional construction methods) should be considered lightweight construction. Listed below are some readily identifiable building features that can give clues as to how a building is constructed and what firefighters can expect to find inside the building as they arrive.

Gable Vents

Gable vents were used extensively in residential building construction prior to the proliferation of lightweight construction. Gable vents are most often rectangular louvered vents found near the peak of the roof on the ends of a building (sides B and C). They can also be found in different shapes, however the rectangular shape is the most common. The purpose of the gable vents is to provide venting for the attic space. The presence of gable vents may indicate that the building was built employing traditional construction techniques and materials.

Soffits

Soffits or eaves of a building are found where the roof meets the exterior side wall of a building. Older building construction techniques did not employ the use of soffit vents, and the soffit itself was a continuous wooden feature nailed to the building. The presence of ventless soffits or eves may indicate that the building was built employing traditional construction techniques and materials.

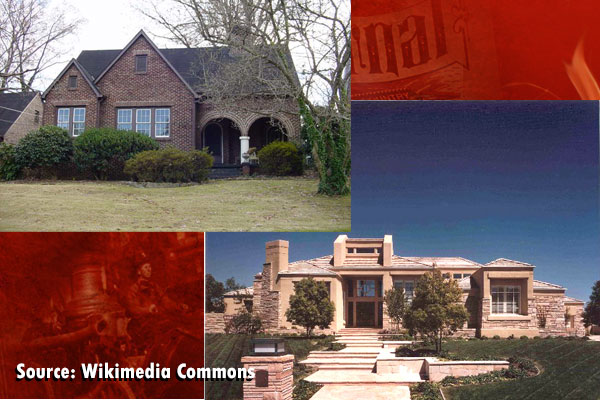

Soffit Vents and Ridge Vents

The use of a combination of soffit vents and a ridge vent is a strong indicator that the building is built employing lightweight building construction techniques and materials. Soffit vents are vents installed in the soffit or eaves of a building and may be made of aluminum or vinyl. The ridge vent is a continuous vent that is built into the roof assembly that is covered with the same roofing shingles as the rest of the roof. It appears as a two to three rise at the peak of the roof. Soffit vents work in combination with ridge vents. Fresh air is drawn naturally in at the soffit vent and circulated in the attic space and is vented out the ridge vent. When fire makes contact with the soffit vent, it will fail and the fire will quickly spread to the attic space, threatening the unprotected roof trusses.

Roof Scuttles

Roof scuttles or hatches were built into older buildings for access to the roof and chimney and are often found near the chimney. The presence of roof scuttles usually indicates that the building was built employing traditional construction techniques and materials.

Building Foundations

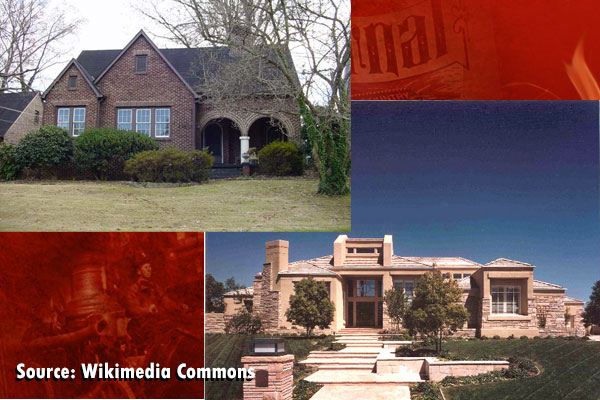

Building foundations can provide a hint of the building’s age. New construction and certainly buildings built using lightweight construction techniques and materials will have a smooth, continuous concrete foundation. The foundation may show only a few inches of concrete or, in the case of a full basement, two or more feet of smooth continuous concrete. Window frames found in the foundations will either be constructed of steel or wood. The wooden window frame usually indicates it is a feature of an older structure whereas a steel window frame may indicate a newer constructed structure. Buildings that show a stone, brick, granite, or a mixture of concrete and stone usually indicates that the building was built employing traditional construction techniques and materials.

Bricks

Bricks, or what appear to be bricks, can also provide insight as to the building’s age and construction. A true brick wall will be a thick wall that supports the building. A brick veneer wall will be only a single vertical thickness of brick with the only purpose to enhance the aesthetics of the building. A brick veneer building should be considered to be a lightweight constructed building until proven otherwise.

A true brick wall will have two different courses of brick. Most of the courses will consist of bricks laid so that the long side is visible; these are called stretcher courses. Every five to seven courses you will find bricks laid so the short end is visible; this is called the header course. The header course adds strength to the wall and is usually indicative of a building built employing traditional construction techniques and materials.

Chimneys

Chimneys are usually visible as you approach the building and can provide a clue of the building’s age and construction. Buildings that show a brick or masonry chimney with a terracotta/tile flu usually are buildings built employing traditional construction techniques and materials. Chimneys that are boxed in, covered with the same siding material as the rest of the building, and have a chimney flue pipe exposed are indicative of lightweight construction.

Be mindful that there are many construction features and materials that can be found on both traditional legacy construction and lightweight construction, and therefore are unreliable as an indicator of what construction technique was used. Building components such as vinyl siding, driveways, electrical service drops, windows, lintels, railings, and outside lighting can be found to varying degrees in all buildings and are therefore not helpful in determining a building’s age and construction.

Many older buildings have seen renovations using lightweight materials and appear to be lightweight when in fact the core structure is of a traditional legacy construction. At the same time, there have been many construction projects that appear as though the building was built in the late 1800s in an effort to match the surrounding buildings, and this newly constructed building is completely a modern lightweight structure. The best way for firefighters to know what type of construction is in their district is to stay current with all construction and renovations occurring in their district. Staying current means that you have to get out in your district and look at what is being built or renovated. Get out of your truck and walk around these construction sites and take a close look at how the building is being built, the materials used, and how it is fastened together. This knowledge will be invaluable if there is a fire in that building, but it will also increase your knowledge of building construction techniques and materials in general.

The list of building features discussed here is not intended to create an absolute rule in identifying building construction techniques and materials, but rather to set some guidelines and target points in your size-up as you arrive on the scene of a building fire.

References

1. NFPA, “Fire Loss in the United States During 2014”

2. Gary Bowker, FDSOA, “Dangers of Lightweight Construction”

Thomas N. Warren has more than 40 years of experience in the fire service in both career and volunteer departments. He retired as assistant chief of department of the Providence (RI) Fire Department after 33 years of service. Presently he is a faculty member at Bristol Community College in the Fire Science Technology Program teaching a variety of subjects in the fire science discipline. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in fire science from Providence College, an Associate’s Degree in business administration from the Community College of Rhode Island and a Certificate in Occupational Safety and Health from Roger Williams University.

Thomas N. Warren has more than 40 years of experience in the fire service in both career and volunteer departments. He retired as assistant chief of department of the Providence (RI) Fire Department after 33 years of service. Presently he is a faculty member at Bristol Community College in the Fire Science Technology Program teaching a variety of subjects in the fire science discipline. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in fire science from Providence College, an Associate’s Degree in business administration from the Community College of Rhode Island and a Certificate in Occupational Safety and Health from Roger Williams University.

More Thomas N. Warren

How Do You Prepare Yourself for Duty?

Elevator Rescues

Taking Command

The Dangers of Fire Escapes

Fire and EMS Responses to Violent Incidents: Tactical Considerations

It Wasn’t Always This Way: Remembering Chief Bennett