Photos by Alexander C. Black

Defensive Responding

STRATEGY & TACTICS

Your life-and-death decisions begin when you climb onto a fire apparatus.

“GET OUTT” shouts the firefighter at the watch desk. “All companies respond to North Third and Water streets! A reported house fire!”

He acknowledges the receipt of the alarm, hits the button to raise the large firehouse doors, and hands the hard copy of the alarm location and address of the fire to the officer who is first to appear on the apparatus floor. Other firefighters converge on the apparatus floor from many different locations: Some arrive via the brass pole; some through doors of adjacent rooms; others from stairs to the second floor of the firehouse. They all head toward the pumper and ladder trucks parked in the center of the apparatus floor.

The apparatus engines start up. This adds urgency to the movements of the firefighters as they don their turnout gear. The firefighter at the watch desk quickly steps into his boots, jumps onto the back step of the pumper, and secures his helmet just before the pumper rolls out of the firehouse into the afternoon traffic. Even with siren wailing and red lights flashing, several blasts of the air horn are needed before the cars stop and allow the pumper to enter the flow of traffic.

The firefighter on the pumper’s back step slips his left arm into the metal hand grip above the hose bed, tosses the turnout coat over his right shoulder, and slips his arm in the sleeve. Then he repeats the action for the other arm, all the while maintaining a hold on the hand grip. As the pumper enters the highway and picks up speed, the firefighter snaps the clips of the turnout coat and pulls his gloves from his pocket. Now fully geared up, he faces the front of the responding apparatus, firmly grasping the hand grips. He leans backward slightly.

The pumper approaches the corner of North Street, onto which it will turn right. The firefighter on the back step signals a right turn with his outstretched arm to warn drivers behind the pumper to slow down. The apparatus accelerates after the turn. The front wheels hit a bump in the road and the firefighter quickly bends his legs at the knees to absorb the vibrations of the back step.

The responding engine approaches the main intersection of town with siren and air horns sounding. The traffic light is in its favor. Vehicles approaching the intersection from other roads are partially hidden from view by large trees that line the streets. Through the tree branches, however, the firefighter on the back step sees a trailer truck heading toward the intersection at high speed.

The traffic light ahead of the fire apparatus turns yellow and the chauffeur sounds the air horn harder and longer. The firefighter on the back of the pumper, realizing that the chauffeur doesn’t see the oncoming trailer truck, moves to the other side of the back step. away from the approaching truck.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

DEFENSIVE RESPONDING

The chauffeur suddenly sees the oncoming truck and hits the brakes. The trailer truck driver sounds several blasts of his air horn and hits his brakes. The pumper skids forward. The trailer truck jackknifes out of control.

The sickening sound of metal striking metal cuts through the afternoon air as the trailer truck rams the side of the fire apparatus. The impact of the collision spins the pumper around 90 degrees. The firefighter on the back step is lifted into the air. His hands are torn from the hand grips and he is hurled forward. Arms outstretched, he flies 50 feet and slams down on the pavement. His helmet and boots fly from his body upon impact. Streaks of blood trail the firefighter’s body as it slides facedown across the road. His head strikes the tire of a stopped auto, snapping his neck. The lifeless body continues its slide under a parked car.

QUESTION 1: What is the most dangerous position on afire apparatus for a firefighter when responding to or returning from an alarm?

- Seated in an enclosed cab, secured by a seat belt.

- Seated in an open cab, secured by a seat belt.

- Standing on the back step, secured by a restraining belt.

- Standing on the back step of a pumper or side step of a ladder truck, holding onto a secure part of the apparatus.

QUESTION 2: Who is responsible for an accident when the apparatus strikes an object or vehicle when operating in reverse gear (backing up)?

- The officer.

- The driver.

- The firefighter riding on the apparatus.

- The object or vehicle.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 1: The correct choice is D. Standing on a back step or side step is the most dangerous position for a firefighter on a responding fire truck.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 2: The correct choice is C. The person responsible for an accident that occurs when an apparatus operates in reverse (backs up) and strikes an object is the firefighter sitting in the apparatus. All firefighters should be off of the apparatus and guiding the driver when the fire truck is operating in reverse gear.

A firefighter makes many life-and-death decisions during a tour of duty, but the first and most important one is climbing onto a fire truck that’s been called to respond to a fire. Whether you have your turnout gear on or not, whether you choose to ride the back step or side passenger compartment, whether you snap on the seat belt or restraining belt on the back step—these are some of the first life-and-death decisions a firefighter makes during a tour of duty.

Many firefighters believe that the chauffeur is responsible for their safety during response to an alarm and return to station. This is wrong. A close look at reports on firefighter fatalities and injuries during these situations reveals that many of the tragedies are caused or could have been prevented by the firefighter killed or injured, not by the chauffeur of the apparatus.

In the past several years the fire service has been affected by so-called “right-to-know laws” passed by the federal government. They tell us, among other things, we have a right to know about hazardous materials stored in our community and about toxic emissions given off by diesel exhaust fumes of the fire apparatus in quarters. Let’s add to the list: We have the right to know that we are responsible for our own safety and survival when responding and returning—the driver or officer is not. We are not passengers on the fire apparatus. The driver and officer do not say, “Leave the driving to us.”

Just as every driver of a fire apparatus should have a “defensive driving” attitude, so should every firefighter who climbs aboard do so with a “defensive responding” attitude. What is defensive responding? It’s knowing that certain riding positions on a fire truck are more dangerous than others and using the safest available; it’s knowing the safest side of the fire truck to climb aboard when responding; it’s knowing how dangerous the roadway intersections are to the responding fire apparatus; it’s knowing how to assist the driver of the fire truck through a narrow roadway or double-parked cars; it’s knowing how to operate safely at a fire on a high-speed highway. Defensive responding is realizing that responding to and returning from alarms is just as dangerous as the hazards faced on the fireground itself. It’s knowing that the entire company, not just the driver and officer, is responsible for the safe arrival of the apparatus to the scene of the fire and its safe return back to station. Safe responding, like safe firefighting, is a team effort.

RIDING POSITIONS ON A FIRE APPARATUS

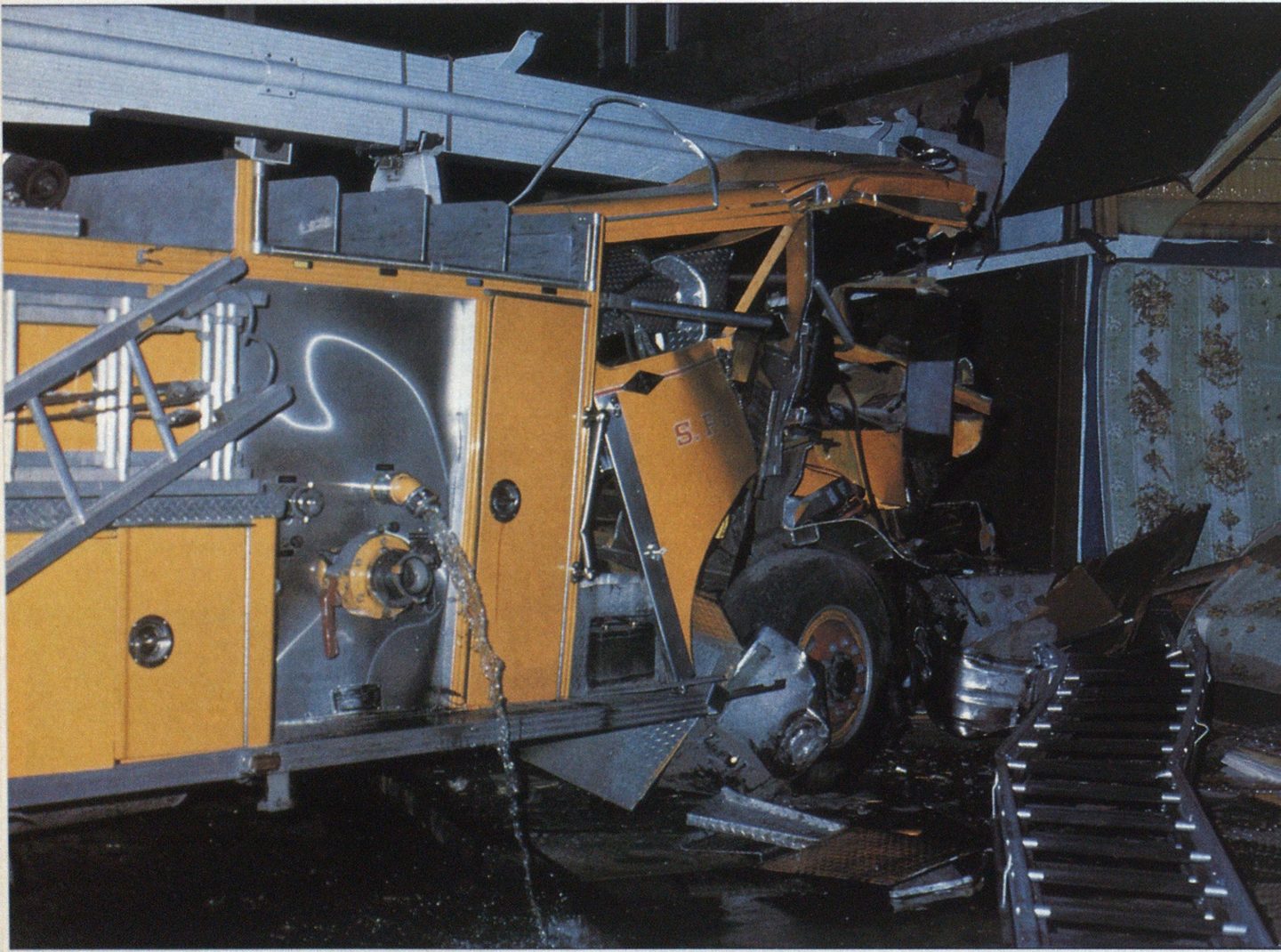

The decision to ride either in one of the enclosed passenger compartments (when available) or on the back step is critical. A collision with another vehicle or a sharp turn could cause a firefighter on the back step to lose his grip, in which case he will most likely be killed or permanently injured by the fall to the roadway or be run over by another vehicle. If the firefighter secures himself to the apparatus back step by a restraining device, a spinal chord injury could occur during a collision. When a firefighter has a choice (many fire apparatus have only the back step and do not have a passenger seat compartment for firefighters) and yet climbs aboard a back step of the pumper or the side step of a ladder truck during a response, a bad decision has been made.

There are four riding positions on the modern fire apparatus. Each provides a different degree of safety during an accident, and firefighters should be aware of them.

Some fire departments prohibit firefighters from riding on the back or side step of a fire truck. These departments have or are planning to purchase vehicles that have enclosed seating for all responding firefighters. In any event, company or department policy should mandate riding positions on all existing apparatus based on degree of safety in case of accident. If the choice is still yours, ask yourself, “Is this the safest position I can choose?”

CLIMBING ON AND OFF A MOVING FIRE APPARATUS

The safest time to climb onto and step off a fire truck is when it’s stationary. At the fire station, responding firefighters should quickly assemble on the apparatus floor near the vehicle and don all protective clothing. Then they mount the apparatus—while it is stationary. The officer, when assured that everyone is aboard, gives the signal to the driver to respond.

Some departments that do not have traffic control signals activated from quarters use other boarding procedures: These require that firefighters assemble on the apparatus floor, don all protective clothing, and assemble outside to stop traffic. The apparatus driver moves the vehicle to the middle of the roadway after traffic has been stopped. At this point all firefighters climb aboard. The signal is given to the officer when everyone is safely on the apparatus. Then he gives the order to respond. Either way, firefighters should only board the vehicle when it is stationary.

During the course of a firefighter’s career, however, he may have to jump onto or step off a slow-moving fire apparatus. Firefighters should know that this practice can be deadly even when the vehicle is moving slowly. They should know that firefighters have been crushed to death beneath the wheels of moving fire apparatus when failing in their attempts to jump aboard. Deadly head injuries have been suffered by firefighters who step from fire apparatus before they’ve come to complete stops: The firefighter steps off the moving vehicle with one foot, is propelled forward, and cannot get the other foot down on the ground fast enough to break into a run. He pitches forward, striking his head on the ground, risking being run over by his own apparatus.

FIREFIGHTER DEATHS BY TYPE OF DUTY

STRATEGY & TACTICS

DEFENSIVE RESPONDING

Defensive responding requires that a firefighter respond quickly to the apparatus floor when an alarm is received in the firehouse so that he has adequate time to don turnout gear and get on the apparatus before it starts to move. After the fire has been extinguished, the defensive responder is always alert to the officer’s signal to board. Chances of injury are great when the firefighter, having missed the signal, must catch up to the moving vehicle. If he is only able to run fast enough to get one foot up on the back step but not the other, he could fall forward and strike his head on the edge of the moving apparatus.

CLIMBING ABOARD A TURNING FIRE APPARATUS

Jumping onto or off of a moving apparatus is dangerous enough; climbing aboard a turning apparatus is even more so, and doing that on the side that’s “into the turn” is more dangerous still. If the firefighter misses the step of the moving fire apparatus and falls to the roadway, chances are great that the rear wheels will run over him before the driver can stop the vehicle. A firefighter who falls in an attempt to board an apparatus from the outside of its turn will be moving away from the direction of the vehicle and, although he still risks injury, at least the rear wheels are not likely to pass over him.

The officer in command of the fire apparatus is usually held responsible by department personnel investigating the types of accidents mentioned above. The officer must always be assured that all firefighters are properly and safely boarded before giving the order to proceed. However, in most instances the firefighter who falls and is injured or killed must also bear some responsibility.

OPERATING AT THE SCENE OF A HIGHWAY ACCIDENT OR FIRE

Firefighters operating at a motor vehicle fire or extrication on a highway are in the greatest danger, not from the flames or leaking gasoline but from the oncoming, speeding trucks and cars. Each year firefighters crossing highways during emergency operations are struck by passing vehicles and killed. Firefighters operating hoselines are crushed to death when speeding vehicles rear end parked fire trucks.

When a fire company arrives on the scene of a highway emergency and there are no police on hand to control traffic, firefighters themselves must first control the oncoming vehicles before safely drawing their attention to the emergency. The fire apparatus should be parked on the highway shoulder if possible. Warning signals or flares should be placed in the roadway to warn oncoming vehicles. A firefighter who is directed to stop highway traffic must never turn his back on oncoming vehicles; nor should he believe that the oncoming vehicles will stop for red warning lights, flashlights, or flags, or because he’s dressed in firefighting clothing. He must always face oncoming traffic and be prepared to jump out of the way at a moment’s notice.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

DEFENSIVE RESPONDING

Roadway warning devices must be properly and prominently displayed. The firefighter must judge the distance required to stop a vehicle traveling 60 miles per hour. He must also consider the effect that a downgrade, a curve in the road, darkness, and weather conditions have on stopping distance. Warning devices on a high-speed highway should be placed at least 350 feet from the fire apparatus and positioned so that they are visible to an oncoming motorist for at least another 350 feet before that. This will give the driver 700 feet to stop a vehicle once he perceives the danger. A curve or upgrade will require that the warning signal be placed farther than 350 feet away from the fire apparatus.

To determine a vehicle’s total stopping distance, three factors must be considered:

- Perception time—the time it takes for the driver to realize a danger exists on the roadway. This is estimated at ¾ of a second.

- Reaction time—the time it takes to move your foot from the gas pedal to the brake. This is also estimated at ¾ of a second.

- Braking distance—the distance a vehicle moves after braking.

Compute the total stopping distance of a vehicle traveling at 60 mph as follows. Remember a simple rule of thumb to convert miles-per-hour to feet-per-second: Multiply the vehicle speed by 1.5 (60 mph = 90 ft./sec.).

If a flare or warning device is placed in the roadway 350 feet before the emergency scene and it is visible from 350 feet away, a truck moving at 60 mph will stop just before the warning device. The additional 350 feet between the warning device and the apparatus will provide a safe distance within which to operate and provide a safety factor against vehicles with defective brakes or against motorists who are driving while impaired and can’t see the emergency scene.

INTERSECTIONS

Highway/roadway intersections are extremely dangerous places for responding firefighters and civilian motorists alike. The intersection accident has proven to be the most deadly to all concerned.

When the responding apparatus approaches an intersection against a traffic signal—even with red lights and sirens displayed, as required by law —the apparatus chauffeur must be certain that the right-of-way has been yielded by all oncoming motorists before proceeding into the crossroad. The defensive fire department driver downshifts or slows down, gently pumping the brakes, upon approaching an intersection. That way, if traffic fails to yield the right-of-way to the apparatus, the chauffeur will be able to make a complete stop before reaching the intersection.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

DEFENSIVE RESPONDING

The defensive fire department driver slowly proceeds into the intersection and passes through it only after he is certain that all other motorists see the fire apparatus, are slowing down, and are capable of coming to a complete stop. Some fire departments require that drivers bring the apparatus to a temporary stop at every intersection when responding for the benefit of both firefighters and civilian motorists.

“SQUEEZE-THROUGH”

The “squeeze-through” accident is the most common collision involving fire apparatus. It occurs when the apparatus must squeeze through a narrow space—a street with cars parked on both sides or even double-parked, for instance. The size of the restricted roadway is misjudged or the vehicle is not maneuvered through the space at the correct angle and the fire truck strikes one or more parked cars.

There are usually no injuries at a squeeze-through accident. The damage is often minor. The ramifications of such an accident, however, can be of major importance to fire department operations and life safety at the scene of a fire: The law requires that the fire department remain at the scene of the accident. If the accident is minor, the officer in charge of the company, then, must do one of two things: either order the entire company and apparatus to remain at the scene of the accident for the official police investigation or order that one firefighter stays behind while the rest of the company continues response, to return later after response has concluded. In the first instance, the community loses the services of the fire company at the fire scene. In the second, the company arrives at the fire minus one firefighter. For a three-member company, the second alternative means that they’ll be seriously undermanned, and that could mean the difference between life or death at a serious fire.

Responding firefighters who encounter a restricted roadway should take several defensive actions to assist the driver and prevent a collision. They should get off the apparatus and request the driver of the double-parked car or truck to move. If the driver is not in the vehicle and there is enough room to pass, the firefighters should guide the driver through the restricted area of roadway. The company officer can also assist the driver in this situation. He, not the driver, is responsible for determining whether there is sufficient space for the apparatus to proceed. If there is, the officer should shut off audible warning devices so the driver can concentrate on the difficult maneuver. Company firefighters should be positioned to guide all sides of the apparatus. If the officer decides that there is not sufficient space for the apparatus to proceed, he must order the driver to back out of the street, guided by the firefighters. The communications center should be notified of the delay in response.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

DEFENSIVE RESPONDING

This sometimes time-consuming procedure may appear to be against everything we are taught about a quick response and receiving the right-of-way by sounding the apparatus sirens. Yet, the service a fire company provides for a community is based on dependability, not speed. Arriving at the scene of an emergency when called —not how long it takes us —is the number-one priority of a fire department. A momentary delay is better than never arriving at the scene because you’ve become involved in a squeeze-through accident.

THE FIRE APPARATUS IN REVERSE

In the aftermath of squeeze-through accidents, many review boards have assigned responsibility to the officer if the collision has involved the right side of the apparatus and to the driver if the collision has involved the left side. Accidents that occur when the apparatus is operating in reverse gear are most often attributed to the fault of firefighters other than the driver.

Firefighters should never be riding on an apparatus that’s operating in reverse; they should be off the rig and in the roadway, assisting the driver. The dangers associated with such a common action should never be underestimated. Anxious motorists have attempted to pass apparatus that, in returning to quarters, have stopped momentarily to reverse gears. Firefighters stepping off the fire truck have been struck by these oncoming automobiles and killed.

Before the returning apparatus backs into quarters, all traffic must be stopped by firefighters. Defensive responding requires that they face oncoming traffic and use flashlights at night. They must be ready to jump out of the path of an auto driven by a drunk or reckless driver. After traffic has been stopped, one of the firefighters takes a position near the firehouse entrance doors, on the officer’s side of the apparatus, to help guide the driver and warn him should it appear that the vehicle will strike an object. This firefighter is also responsible for preventing impatient pedestrians from dashing into the path of the fire truck. Only when the fire apparatus is completely off the roadway and into the firehouse should the order be given to allow traffic to proceed. Firefighters in the roadway should face waiting traffic during the entire backing-up operation. They must be prepared for a surprise move by an overanxious motorist in a line of traffic who sees that the apparatus has pulled into quarters but is unaware that firefighters are still in the road.

The hazards in responding to and returning from alarms are increasing. They are too great to place the responsibility for safety solely on the firefighter operating the vehicle. Defensive responding requires a team effort by all members on the apparatus—the safety of all is at stake.