OSHA Standards for Fire Service

features

Although there have been various organizations with powers to regulate employee safety, the fire service, both municipal and industrial, has been pretty much excluded from such regulation. As of last Dec. 11, that has changed. You may now find yourself confronted with new safety standards which have been mandated by federal or state law.

The safety standards to which I refer are the revised Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) fire protection standards. To those of you in the private sector OSHA is certainly no stranger. Those of you in the public sector, however, may have had little or no involvement with OSHA.

Those of you who have heard of the revised OSHA fire protection standards probably are somewhat confused. Even those of you who have read the text may be confused by the language in the Federal Register. It is the intent of this article to help reduce some of this confusion by explaining some of the major revisions and identifying possible effects on both the private and public fire service.

No longer debatable

The time for debate is past since the standards became law on Dec. 11. To many, the standards should represent a major victory in the battle to improve safety in fire fighting. To others, unfortunately, they may represent a disruptive challenge or threat to two of the most cherished facts of the fire service—our autonomy and tradition.

In 1970, Congress directed OSHA to draw up standards that would ensure, so far as possible, safe and healthful working conditions for everyone in the country. On May 29, 1971, OSHA promulgated 29CFR, Part 1910, Occupational Safety and Health Standards, Subparts A through S, which were intended to help prevent personal injury and loss of life in the workplace. Subpart L dealt exclusively with fire protection in the workplace and for the most part tracked with the consensus fire protection standards of the day.

As time went on, OSHA gradually revised its standards. In 1978, a proposed major revision to Subpart L was first published. During the next two years, the public was invited to comment on the revised document and asked to submit suggestions at public hearings conducted nationwide by OSHA. In November 1979, the official comment period closed. The final revisions were published in the Federal Register of Sept. 12, 1980, and became effective Dec. 11. The standards affect all employers in the private sector with the exception of those in construction, maritime occupations, and agriculture.

Wider coverage states

In addition, the standards cover every paid and volunteer fire fighter in the states of Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming, and the territories of the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico. All of these have cooperative agreements with OSHA.

Of major significance is the fact that OSHA no longer places emphasis on protection of the workplace as a means of protecting the employee. Rather than specifying levels of protection, OSHA has specified minimum performance requirements for the protection level.

The key revisions are in the areas of fire brigades, portable fire protection equipment and fixed fire protection systems. Of major concern should be the revisions dealing with fire brigades and portable fire protection equipment.

Impact of standard

OSHA defines a fire brigade as “an organized group of employees who are knowledgeable, trained and skilled in at least the basic fire fighting operations.” The term “fire brigade” is not often associated with municipal fire departments, yet every fire fighter, paid or volunteer, is in fact an employee of his department or municipality. It is through this definition that municipal fire departments will be impacted by OSHA.

Subpart L states: “OSHA does not require employers to establish fire brigades or require employees to fight fires. If the employer elects to totally evacuate all employees from the workplace at the time of a fire, the employer may do so. However, if the employer elects to have some or all of the employees fight fires, then some kind of personal protective equipment or training or both will be necessary, depending upon the degree of fire fighting the employees will be doing.”

The key to the revision is that OSHA requires that the employer inform the employee in writing (by oral communication if 10 or less employees) as to what actions the employee is to take during a fire.

“The extent of education or training and equipment provided by the employer is to be consistent with the employees’ exposure to fire fighting hazards.1

OSHA defines training as “the process of making proficient through instruction and hands-on practice in the operation of equipment,” while education is defined as “the process of imparting knowledge or skill through systematic instruction.” It does not require formal classroom instruction.

OSHA’s philosophy is that the mere presence of fire fighting equipment does not guarantee employee safety. What does protect employees is the knowledge or skills they have in using the equipment. If the equipment is provided with no training or education, then the equipment is of little value to employees.

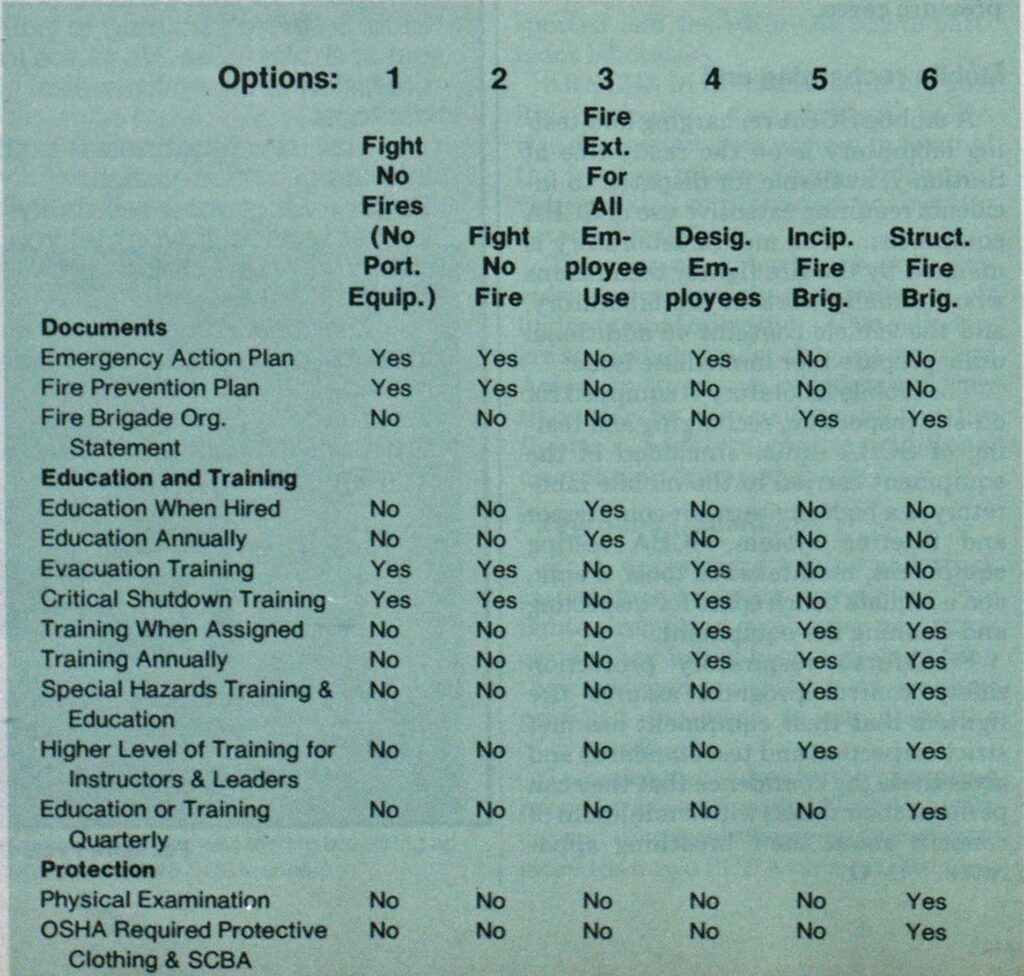

The employer must choose one of the six options which follow, inform employees as to what is expected of them, and then provide the requirements as outlined by OSHA.

“The portion of the standard directed to fire brigades is intended to assure that employees who must fight fires are provided with adequate personal protective equipment, training, and leadership to assure their safety and health during firefighting and rescue operations.”1

One of the following options must be selected to complete the statement: “In the event of fire:”

OPTION 1

Employees will evacuate the building. (No portable fire protection equipment available.)

An employer may elect to have all employees evacuate the workplace in the event of fire. If so, he is not required to provide portable fire fighting equipment, but must provide a written emergency action plan and a fire prevention plan. The emergency action plan must include: methods of announcing and reporting fire emergencies, types of evacuation, emergency escape routes, emergency escape procedures, procedures for shutting down critical plant operations, methods for accounting for evacuated employees, rescue and medical duties of personnel, and the names or titles of personnel or departments that can further explain the emergency duties.

The fire prevention plan must describe: major workplace fire hazards, proper handling and storage practices for hazardous materials in the workplace, potential ignition sources, types of fire protection equipment available, types of fire protection systems installed, names and titles of personnel responsible for maintenance of fire protection equipment and systems, housekeeping procedures designed to control flammable and combustible waste materials and residues, and maintenance procedures for equipment and systems installed on heat-producing equipment to prevent accidental ignition of combustible materials. In addition to these plans, OSHA requires that evacuation training and critical operations shutdown training be provided.

OPTION 2

Employees will evacuate the building. (Portable fire protection equipment provided.)

In some cases, the employer may be required by the local authority, insurance carrier, etc., to provide portable fire fighting equipment, but may elect to have no one trained in its use. If this is the case, the employer must meet the same requirements as in Option 1, and is further required to have the portable fire equipment maintained and tested in accord with current standards.

OPTION 3

All employees will use portable fire equipment in their immediate work areas.

1Federal Register,” Vol. 45, No. 179/Friday, September 12,1980/Rules and Regulations; “Part III, Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Fire Protection; Means of Egress; Hazardous Materials: Final Rule.”

In this case, the employer must provide education to every employee when first hired and annually thereafter. This education must cover the basics of fire extinguisher selection, use, etc., and should be varied each year.

OPTION 4

Portable fire equipment shall be used only by “designated employees” in their assigned areas.

In this case, the designated employees are not an organized team and do not fight fires outside their respective areas. These employees must be trained in the use of portable equipment when first designated and annually thereafter. Since only a few employees in each area will fight fires, and emergency action plan must be provided for the other employees. OSHA also permits extinguishers to be grouped in this case, thus exempting the employer from spacing and travel distance requirements for extinguishers.

OPTION 5

Portable fire equipment will be used by a fire brigade to fight incipient stage fires only.

OSHA has defined two types of fire brigades. One is to fight “incipient stage” fires only and the other is to fight all fires, including “interior structural fires.” The key definition here is “incipient stage.” According to the OSHA standards, “Incipient stage means a fire which is in the initial or beginning stage and which can be controlled or extinguished by portable fire extinguishers, Class II standpipe or small hose systems without the need for protective clothing or breathing apparatus.”

Should an employer elect to have this type of brigade, he must develop a written fire brigade organizational statement which establishes the existence of the brigade and should include: the basic organizational structure, the number of members, the type, frequency and amount of training to be provided and the expected functions of “the members (i.e., incipient fire fighting, emergency first aid, etc.). Management must identify the tasks which it expects the fire brigade to complete, then ensure that training is commensurate with the assigned tasks. Members must be trained prior to performing emergency activities.

The following must be provided: annual hands-on training in the use of fire extinguishers and small hose lines (5/8 to 1 1/2-inch), training and education regarding the special hazards present in the workplace, and written operational procedures for dealing with them in emergencies. Fire brigade leaders and instructors must be provided with training and education which is more comprehensive than that provided to general members.

Since many industrial fire brigade members are also volunteer fire fighters, the employer need not duplicate the training that the members complete in their fire departments. However, training must have been completed within the past year and must be substantiated with documentation. This does not relieve the employer from the responsibility of conducting training and education regarding the special hazards and problems associated with the particular workplace.

OPTION 6

The fire brigade will fight all fires including “interior structural fires.”

Interior structural fire fighting is defined as “the physical activity of fire suppression, rescue, or both, inside of buildings or enclosed structures” (defined as a structure with a roof or ceiling and at least two walls) which are involved in a fire situation beyond the incipient stage.1

Where management elects to have this type of brigade it must also provide a fire brigade organization statement identifying those items mentioned under Option 5.

In addition, all members assigned to this type of fire brigade after last Sept. 15 must pass a physical examination to prove that they are physically capable of performing those tasks identified in the organizational statement. For employees assigned to the brigade prior to Sept. 15, 1980, the exam becomes mandatory on Sept. 15, 1990.

The training requirements for this type of brigade are basically the same as outlined for brigades fighting incipient stage fires. In addition, education or training on a quarterly basis is required. These brigade members must be provided with OSHA-required protective clothing and breathing apparatus.

Protective clothing

OSHA has recognized protective clothing as a key issue in the safety of those who fight fire. Fire brigades expected to combat interior structural fires must be equipped with protective clothing. The employer is responsible for seeing that this equipment is provided and properly worn during structural fire fighting. Protective clothing ordered or purchased after July 1,1981, must meet the requirements of OSHA, while clothing and equipment ordered or purchased prior to that date must be replaced with OSHA-required equipment by July 1, 1985.

Protective clothing must be provided in accordance with the OSHA standard (1910.156) as follows:

Foot and leg protection shall be provided in the form of fully extended boots or protective shoes or as boots worn in combination with protective trousers.

Body protection must be coordinated with foot and leg protection. This can be done by providing a fire-resistive coat and trousers in combination with protective shoes or boots or by providing a fire-resistance coat in combination with fully extended boots. The performance, construction, and testing of coats and trousers should be at least equal to those outlined in NFPA Standard No. 1971 (1975), “Protective Clothing for Structural Firefighting.” OSHA permits two exceptions to the 1971 requirements: (1) The tear strength requirement of OSHA is only 8 pounds in any direction as opposed to the NFPA requirement of 22 pounds. (2) The outer shell may discolor or char when placed in a forced air laboratory oven at a temperature of 500°F for a period of five minutes. NFPA does not permit discoloration or charring.

Hand protection must consist of protective gloves or a glove system which provides protection against cuts, punctures, and heat penetration. The gloves or glove systems must meet the test requirement of the 1976 National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) publication, “The Development of Criteria for Fire Fighters Gloves, Vol. II, Part II: Test Methods.”

Head protection must consist of a protective head device with ear flaps and chin strap and must meet the performance, construction, and testing requirements presented in the United States Fire Administration’s 1977 publication, “Model Performance Criteria for Structural Fire Fighters’ Helmets.”

Eye and face protection must be provided and may take the form of separate devices, accessories to protective head devices, or full facepieces, helmets, or breathing apparatus hoods that comply with Sections 1910.133 or 1910.134 of the OSHA standard.

Self-contained breathing apparatus

Respiratory protection must be provided by devices that comply with 1910.134 and 30CFR Part II. Selfcontained breathing devices used to fight fires must have a minimum of 30 minutes duration.

Self-contained breathing apparatus ordered or purchased after July 1,1981, must be of the positive-pressure type. As of July 1, 1983, all self-contained breathing apparatus must be of the pressure-demand or some other positive-pressure type. Demand apparatus which can be switched from the demand mode to the positive-pressure mode may also be used.

Should an employer demonstrate the need for long-duration breathing equipment, he may use negative-pressure self-contained units with a rated service life of more than two hours and a minimum protection factor of 5000 as determined by acceptable quantitative fit test.

The employer may continue to use this apparatus for 18 months after a positive-pressure unit with the same or longer rated service is certified by NIOSH. After this 18-month period, all long-duration units must be of the positive-pressure variety.

Buddy-breathing OK

It is important to note that OSHA permits the attachments of buddybreathing devices or quick-disconnect valves to self-contained breathing apparatus even though these devices are not certified by NIOSH. Of course, these devices may not interfere with the normal operation of the apparatus.

OSHA also permits the employer to use compressed air cylinders made by one manufacturer in breathing apparatus of another as long as all cylinders have the same capacity and pressure.

OSHA also now requires that all breathing apparatus be inspected at least monthly.

It should be pointed out that OSHA does not require employers to provide a full set of protective clothing for every fire brigade member. The requirements apply only to those brigade members who might be exposed to fires in an advanced stage, smoke, toxic gases and high temperatures. The standards for gear apply only to members fighting interior structural fires and do not apply to protective clothing worn during outside fire fighting operations.

In a word, the impact on industry thus far has been overreaction. There is talk of major employers getting rid of all their fire extinguishers because of the OSHA training requirements and companies are planning to do away with protective clothing and breathing apparatus rather than spend the money to train their people.

Certainly once the dust settles, fire protection professionals will find that the standards do nothing but reinforce the position we have taken for years— that training and education in the use of equipment is far more important than the mere presence of equipment.

In time, I am sure that the fire service will adjust and reap the benefits of the new standard.

This article has highlighted the major revisions which would be of interest to most readers. There are many other revisions of which you should be aware. To learn about those, you should contact your local OSHA office to obtain a copy of the revised standards.