By Richard Mueller

None of us arrive at fire incidents and announce (or acknowledge) a marginal strategy even though all firefighters undertake them. Our too-often-used words of an “aggressive offensive attack” (offensive strategy) simply do not match our actions when we slowly and blindly search for the seat of the fire and/or occupants in low/no visibility. Just because we way say that we are acting offensively does not mean that we are acting offensively. So if we are not offensive, what are we? The marginal strategy acknowledges that it is difficult to be aggressive in low/no visibility, and that a more cautious and calculated approach is appropriate and necessary in such environments that are immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH). The marginal strategy provides an honest and legitimate way to define thinking and corresponding actions in an environment where we might not win.

Tragedies of Strategies

On August 3, 2007,1 a captain and a firefighter died after an extended offensive attack in low/no visibility. On July 22, 2008,2 one firefighter died and three others just barely made it out after the first floor collapsed in low/no visibility, 30 minutes into the fire attack. On July 3, 2010,3 another tragedy of strategy occurs when a captain died after entering a low/no visibility environment with an uncharged hoseline while attempting to locate and extinguish a late-night fire. In all three of these tragedies, no civilians were in the building. The fire service risk management plan clearly states that we will only “risk a lot (our lives) to save a lot (others lives).” Yet even as you read this there are firefighters right now crawling inside of a burning building with no one else inside.

Low/no visibility environments contain the deadliest components of our profession. We all call and know this obscurity as smoke, but in reality it is fuel. This combination of unburned gases and high temperatures in a work environment that we have never seen or worked in before creates orientation and situational awareness challenges that not all of us are able to deal with. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has reported4 that the three leading causes of fatal firefighter injuries (non-heart related) while operating inside of structures has nearly doubled since 1978. These three causes–getting lost, being caught in structural collapse, or being overcome by fire progress–are all the result of working too long in an environment without being able to see and by not respecting this error-producing condition.5 Crawling around in low/no visibility for an extended period of time should not be considered or tolerated as a “normal” firefighting condition.

Some will disagree and say that they can see because they have a thermal imaging camera (TIC). Although TICs are helpful, their effectiveness is limited. Obstructions, insulation, and improper use all reduce our situational awareness as we forge forward while one of us tries to look into and interpret the 3 x 5 screen through a face piece. Some serious limitations of the TIC were highlighted by Underwriters Laboratory in their “Structural Stability of Engineered Lumber in Fire Conditions” research6. During the tests, temperatures of well over 1,200º F below a floor assembly were not detectable from above it using a TIC. Temperature readings taken with the TIC only registered 85º F above the floor. The TIC could not detect the well-involved fire burning below the floor because of hardwood flooring, carpet, and its insulated pad until the floor system was near or at its failure point! The room temperature was ambient while an inferno burned beneath. TICs only measure surface temperature, not what is happening below the surface.

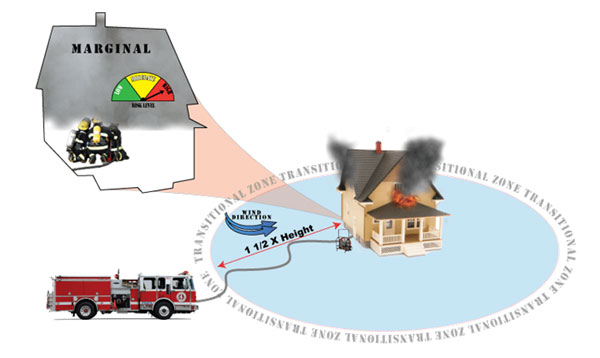

The marginal strategy (1) is defined as an “interior attack with crawling visibility. It is performed on your hands and knees because you cannot see your feet. The risks in this marginal zone are high because of the high possibility of getting lost, wearing the hazard, and/or the structure. Getting lost occurs because of disorientation where you are not orientated to your surroundings because you cannot see them. “Wearing the hazard” implies getting the hazard on you. This includes flame, heat and toxic gases, and looks like smoke, rollover, flashover, and backdraft. Wearing the structure means the loss of structural integrity resulting in the structure coming apart on you. This looks like fire company members who are caught, trapped, or crushed. Because of the realty of these life-taking hazards, marginal thinking and actions should only be tolerated for a short period of time.

(1)

The term “marginal” is not new to the fire service, but looking at it as a strategy is. The word marginal implies an unsureness, a situation that could go either way. Crawling around searching for the fire, especially for extended periods of time, tilt the odds against us by the minute as we get deeper into the unknown. Firefighters can get into trouble when they choose an aggressive-offensive mindset followed by an aggressive interior attack when they cannot see how big and bad or even where the enemy is. Too often, this occurs when we are the only life safety concern inside. The reality of strategy is that we do not always get to choose. Although you may want to be offensive, the incident conditions should have more to say about how we should fight (and how long) rather than our own infallible, ego-driven decision making. We are simply kidding ourselves when we say that we are offensive in marginal/defensive conditions as we crawl slowly in fast-moving fire conditions. The “margin of error” is simply to small to operate in poor visibility for extended periods of time.

10 Minutes

The marginal strategy should only be endured for 10 minutes or less. Marginal should be part of your vocabulary, understanding, and decision making given these factors of today’s firefighting:

- Lightweight building construction (buildings come apart quickly when exposed to heat and fire)

- Occupant survival profiles (high heat and highly toxic fire environments that do not support life)

- Smaller margins of error as a result of poor visibility and disorientation

- Current firefighting technologies that can create visibility quickly (positive pressure blowers), and

- Fire companies that will not stop going inside to put out fire even though no one is inside.

Including marginal into our strategic definitions legitimizes what firefighters do “a lot” every single day (interior attacks in poor visibility) and gives practicality, honesty, and credibility to our risk-management plan (within the parameters of time and visibility). What we do finally matches the risks involved, but just like professional sports teams we will only play for a predefined period of time. At the 10-minute mark, the question that needs to be asked is: “What are we going to save?” Unfortunately, the answer to that question is less than many will admit.

Captain Stephen Marsar of the Fire Department of New York provided some answers in an article entitled “Survivability Profiling, How Long Can Victims Survive In a Fire7.” Some in the fire service did not agree or even like his article (some of his research is cited below), but that does not mean that it is not true.

The NFPA states that the upper limit of human temperature tenability is 212º F. This is well below the temperatures found in most structure fires. Today’s fire environments can easily reach 500º F within three to four minutes, and flashover (with temperatures above 1,000º F) can develop in under five minutes8.

Scientific research on human respiratory burns9 and inhalation of hot gases in the early stages of fire10 reveals that occupants trapped in structural fires have limited survival times. In one experiment (which lasted 11 years), fire victims were tracked if they met three diagnostic criteria of: (1) flame burns involving the face, particularly the mouth and nose; (2) singed nasal mucus membranes; and (3) burns sustained in closed-space interior fires. Twenty-seven patients were treated; 11 additional patients didn’t meet all three of the test criteria or were dead on arrival. Of the 27 patients whose body surface burns ranged from 15 to 98 percent, 24 died (three in the first 24 hours, five within 36 hours). Respiratory burns directly accounted for 18 of those deaths (the others died of other burn injury complications). Sixty percent of the victims were found to have been exposed to heat (most at temperatures above 200º F, however some were below) and humidity for six to seven minutes (remote from the fire area). The fatality rate increased to 90 percent for those exposed to toxic smoke as well, even for only several minutes. The experiment concluded that human fire victims were most susceptible to respiratory burns from heat first, toxic smoke second, and humidly a distant third. The time of exposure for all 24 fatalities was less than 10 minutes. In the second experiment10 (using laboratory mice and human fire victims), lethal first-degree respiratory burns were found to occur in just 230 seconds (under 4 minutes).

Additionally, carbon monoxide and cyanide found in smoke are an ever-present deadly duo. These two killer gases are referred to as the “toxic twins11“ because of their synergistic killing effect on unprotected occupants. A 2006 NFPA study showed that 80 percent of fire victims die from smoke inhalation and 87 percent of people who died in fire had toxic blood concentrations of cyanide as well as carbon monoxide. Heat-release rates from one pound of today’s plastic environment releases as much as 19,000 BTUs as compared to one pound of wood which releases 8,000 BTUs. The toxic smoke produced by the proliferation of synthetic material and extreme temperatures reached in very short time periods contains high levels of hydrogen cyanide, which is 30 times deadlier than that of carbon monoxide alone. At 3,400 ppm hydrogen cyanide (as found in most enclosed structure fires) survival time is less than one minute!

A look at the annual fire death rates in this country and a personal account of your own fire-victim survival rates show few survive when they are unable to self-escape. The 10-minute marginal window may at first seem short, but it is longer than the ability of unprotected occupants to survive in low/no visibility environments.

Secondly, many lightweight structural components have proven to fail sooner than 10 minutes. Research cited previously6 from UL Laboratory has shown that unprotected lightweight engineered I-beams can fail in as little as six minutes–almost half of the 10-minute marginal window, and this does not even factor in your response and set-up time.

The marginal strategy is not a death sentence to the aggressive offensive fire attack. On the contrary, it reinforces the need to more quickly create conditions that allow for an offensive fire attack. Knowing that you will not be allowed to operate for extended periods of time in low/no visibility encourages “transitional” thinking and actions before entry: a 360 to better evaluate where the fire is, opportunities for an aggressive exterior attack, and creating entrance and exit openings to create an air flow path to the fire. This one/two punch of quick water on the fire (transitional attack) and faster smoke and heat removal (positive-pressure ventilation) provide early fire knockout and increased interior visibility more quickly. An 18,000 cfm positive-pressure blower will create almost 10 air exchanges in a 2,000-sq. ft. residence in 10 minutes. If visibility cannot be gained after 10 air exchanges, the fire is simply bigger and badder than we are; there’s a high probability of us losing. It’s time to think and act differently (do something different). Quickly reducing and removing heat and smoke from the structure creates legitimate offensive firefighting.

*

The addition of a marginal (and transitional) strategy to our thinking provides some middle ground and a greater margin of error to our traditional “all or nothing” (offensive/defensive) approach to strategy, where thinking and actions taken between defensive and offensive better ensure victim and firefighter survivability. Looking at fire conditions for what they are rather than as what we want them to be is an honest and intelligent definition of situational awareness. We get to choose the future rather than the other way around. Good outcomes are the result of good thinking. If we truly value life, then we must better understand and respect the error-producing condition of smoke and low/no visibility.

END NOTES

1. “A Volunteer Captain Runs Low on Air, Becomes Disorientated and Dies while Attempting to Exit a Large Commercial Structure — Texas,” NIOSH Report F2010-16, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face201016.html

2. “A Volunteer Mutual Aid Firefighter Dies in a Floor Collapse in a Residential Basement Fire — Illinois,” NIOSH Report F2008-26, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200826.pdf

3. “A Volunteer Mutual Aid Captain and Firefighter die in a Remodeled Residential Structure Fire — Texas,” http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face200729.pdf

4. “U.S. Fire Service Fatalities in Structure Fires, 1997-2000,” Rita F Fahy, Ph.D., NFPA July 2002.

5. The concept of error producing conditions (EPC) comes primarily from the work of J.T. Williams in the late 1980s but is still used in many fields to assess the potential impact of errors. This technique is used in the field of human reliability assessment (HRA), for the purpose of evaluating the probability of a human error occurring throughout the completion of a specific task.

6. “Structural Stability of Engineered Lumber in Fire Conditions,” UL University fire Safety — On Line Courses, UL Laboratory,

https://www.uluniversity.us/DevelopmentPlan/Display.DevelopmentPlan.aspx?RFC=187716

7. Stephen Marsar, “Survivability Profiling, How long can victims survive in a fire?” Fire Engineering, July 2010. http://emberly.fireengineering.com/articles/2010/07/survivability-profiling-how-long-can-victims-survive-in-a-fire.html

8. “Fire Power (video) and Instructor’s Guide,” National Fire Protection Association, 1986

9. Corbitt, Given, Martin, Rhame, and Stone. “Respiratory Burns: a correlation of clinical and laboratory results,” Annals of Surgery, Emory University, Atlanta, Ga., 1967.

10. Liu, Young-Gang, and Zang. “Theoretical evaluation of burns to the human respiratory tract due to inhalation of hot gases during the early stages of fire.” Burns, Vol.32, (San Diego, CA: Elsevier Ltd,. 2005) 32:434-446

11. “To Hell and Back IV: The Toxic Twins (DVD).” People’s Burn Foundation, Indianapolis, IN.

Richard Mueller is a battalion chief for the West Allis (WI) Fire Department. He is a fire instructor for Waukesha and Gateway Technical College and a technical rescue instructor for the WI REACT Center. He is a member of the Federal DMORT V and WI Task Force 1 Team and a Partner with the WI FLAME Group. He is the author of the firefighting textbook Fire Company 4and can be reached at Rick@Wiflamegroup.com