EARTHQUAKE

RESCUE/EMS

“It felt like a giant rolling pin under the ground.”

Four fire fighters and Captain John Donelan, who was conducting a Stokes litter drill in the Coalinga, Calif., fire station last May 2, felt a “rolling sensation” in the ground at 4:42 p.m. Everyone immediately evacuated to the backyard, away from the station.

“We had been warned over and over about earthquakes and had been drilled on how to prepare,” said a Coalinga fire fighter.

Donelan heard a loud popping sound overhead. The truss rods on the 100,000-gallon, 125-foot-high water tower behind the station were breaking. All hands moved to the front of the building.

When the tremor stopped 17 seconds later, all apparatus were removed from the station. The fire station and immediate surrounding buildings were still standing, but a large column of dust rose from a collapsed building one block north of the firehouse on Elm St.

The “rolling sensation” was felt throughout California and as far east as Reno, Nev., registering 6.5 on the Richter scale.

In the absence of Chief Fred Fredrickson, who was attending a chiefs’ convention in Fresno, Donelan, an acting chief, sped to the scene of the collapsed building and ordered an ambulance to respond with him. On the sidewalk next to the collapsed building, a man was found wedged between a parked car and a large pile of bricks. Fire fighters extricated the victim and checked for injuries

Three minutes after the earthquake hit, Donelan proceeded downtown to investigate further damage.

Damage to the city

Sixty-five of the 95 downtown business buildings were wrecked, burned or damaged. Almost all of these were unreinforced two-story masonry buildings. Of the 2700 homes in town, 300 suffered major damage. Most of the residential damage was due to older homes slipping off their foundations. These homes were built before codes required homes to be bolted to their foundations. In all, 2000 of the 2700 homes in town received some type of damage. Total damage to the city has been estimated at over $31 million.

When Donelan saw this destruction on Coalinga Plaza, he ordered the lieutenant at the first building collapse site to join him at the plaza and radioed the Office of Emergency Services (OES) in Fresno for assistance from other agencies and jurisdictions. The OES began sending strike teams of fire engines, ambulances and law enforcement units. The strike teams are made up of five similar units with one leader and common communications.

An alarm to call back all off-duty Coalinga fire personnel and volunteers was initiated. Initial response to the fire station from this call included eight fire fighters.

About 20 citizens, panicked by the earthquake, rushed to Donelan for assistance when he arrived downtown, and he found it necessary to move the command post back to the fire station. Four minutes after the first shock, a second earthquake of 4.5 magnitude struck. Donelan found it impossible to get into his car to use his radio because the car was bouncing violently. This quake was over in a few seconds.

OES in Fresno confirmed that strike learns were responding to Coalinga and that the nearby West Side Fire Department would arrive in 25 minutes with two engines and a battalion chief. At thfc time, a California Department of Forestry (CDF) battalion chief arrived at the command post. Two of the CDF brush fire units were patrolling the residential area looking for injured citizens. A heavy equipment operator was set up at the CDF headquarters, which became the staging area, two blocks from the fire station. This operator later became a staging manager.

The first fire was started in the Coalinga Inn when the 371-square-foot building collapsed, crushing a large shipment of liquor that had been received earlier that day. It was determined that the alcohol either reached a pilot light on a water heater or was ignited by lighted candles on the tables.

The first two engines arrived at the scene at 4:52 p.m., two minutes after smoke was observed from the station. Each engine had only one fire fighter, and local citizens manned five 2 1/2-inch hand lines from these engines to combat the flames. Due to a lack of protective clothing and breathing apparatus and the danger of further collapse, all fire fighting was done from the exterior.

The water system initially stayed intact, allowing the engines to connect their 5-inch supply lines to hydrants. About an hour later, the water supply diminished,. It was discovered afterwards that large chunks of debris in the water system were partially blocking the pumps’ suction screens.

An engine from the West Side Fire Department, under the command 6f Battalion Chief Howard Hawk, arrived at 5:17 p.m and went to work at the rear of me fire with two 2 1/2-inch lines. Due to the collapse, fire streams were unable to reach the seat of the fire. It was decided to remove a partially burned but collapsed jewelry store from the fire’s path with heavy equipment. This succeeded in stopping the fire.

The majority of the collapse in the fire area was masonry, which primarily fell on the sidewalks and only partially into the streets. Some hydrants were covered with masonry but none of the streets was blocked. Prior knowledge of hydrant location proved invaluable.

Three other fires, occurring three hours after the earthquake first struck, all started in kitchen areas under similar circumstances. Objects falling from cupboards struck and activated the controls of electric appliances. For some reason, the electricity was restored three hours into the incident, causing the stoves to ignite the debris on top of them and spreading flames to the rest of the kitchen areas. All three fires were held to the kitchens by fire units responding from the staging area.

Search, rescue and EMS activities

Initially, media reports indicated that 50 people were severely injured and many more were slightly injured. The actual number of severely injured was miraculously held to six people. At the time of this writing, one man was still in a coma after suffering a head injury caused by a collapse; another man suffered two broken legs when civilians too hastily pulled him from beneath a collapsed brick wall. In all, 47 people were treated for injuries, but only the six severely injured required hospitalization.

The initial difficulty for search and rescue personnel was to determine whether anyone was in the buildings before the earthquake hit. A concerted effort by fire personnel, law officers and citizens to contact responsible persons for each building showed that 75 percent of the collapsed businesses were not occupied at the time of collapse.

Once search and rescue efforts discovered persons in need of medical aid, the problem of finding facilities to treat them arose. Even though the Coalinga District Hospital had not suffered any structural damage, all the treatment facilities were damaged due to the quake’s vibrations. No power was available to operate the hospital equipment, so the fire department furnished the hospital with a small electrical generator. The treatment of quake victims, however, mainly involved stabilizing them so they could be moved to another hospital outside Coalinga for extensive treatment.

The Fresno County Sheriff’s Office officially took command of the search and rescue efforts 1 1/2 hours into the incident. Eventually, 125 police officers aided in the search and 27 ambulances were brought in from counties as far away as 150 miles to transport possible victims of the quake. By noon on May 3, 300 workers with heavy equipment were involved in search and rubble removal, often hampered by aftershocks.

All phone service in the Coalinga area was knocked out by the the initial earthquake and by heavy phone use by citizens. Electricity was out as well and portable generators were necessary to establish radio dispatch communications. The Coalinga Police Department experienced difficulty when their generator failed to start.

With so many agencies and jurisdictions involved in the incident, much of the communications had to be made face to face. Most fire units had a common radio frequency, but when communicating between the different agencies, radio frequencies were not available. All fire service jurisdictions communicated

Command of the incident

Initial command was taken by Donelan of the Coalinga Fire Department. Chief Fredrickson returned to Coalinga 1 1/2 hours after the first shock and took command from Donelan. Donelan was appointed operations chief at the scene of the Coalinga Inn fire, and incident command was transferred to Lieutenant D. Greening of the Fresno County Sheriff’s Office. Greening established a command post for the entire incident at the California Highway Patrol office in Coalinga and assembled a representative from each agency and jurisdiction involved at the command post to form a plan for all the resources involved. This proved difficult because the representatives periodically returned to the field and were unavailable at the command post. However, since all agencies and jursidictions involved were familiar with the incident command system being used to handle the incident, the operation basically went well.

The City of Coalinga, Calif., located along the western edge of the San Joaquin Valley, covers 4 square miles. The nearest major city is Fresno, 70 miles to the east.

The population of Coallnga is about 6500. Its primary industries are oil production and agriculture.

The city grew from a 19th century railroad refueling Stop based on the high-sulfur coal mined In Coalinga. Its name evolved from the railroad stop, Coaling Station A.

The Coalinga Fire Department con sists of 11 full-time paid members and 19 volunteers manning three engines and one squad. The department also mans two ambulances 24 hours a day. This service is provided to the corn mualty and the surrounding 700 square miles.

Shift strength for the fire department consists of the chief, 8 captain and an ambulance attendant on call 24 hours, A lieutenant, fire engineer and fire fighter are on 24-hour shifts.

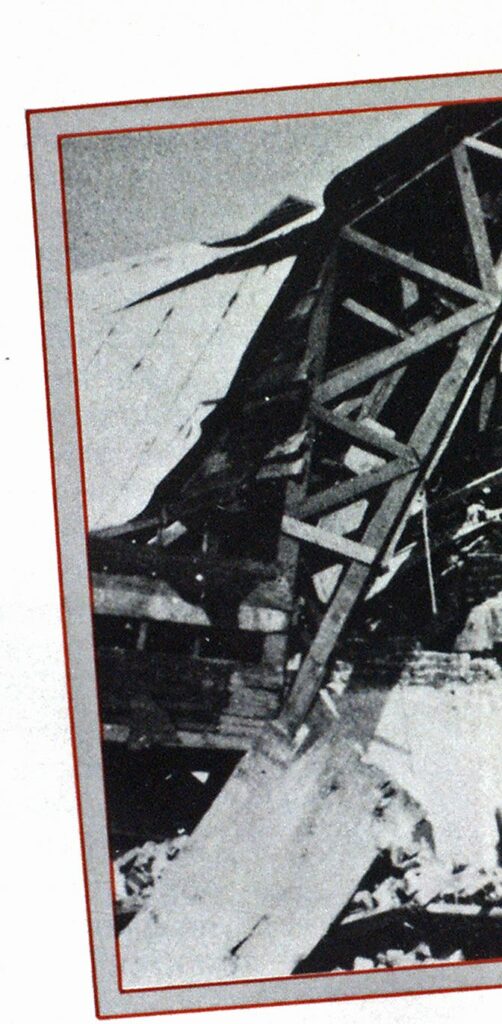

photo by the auther

In a small community such as Coalinga, the immediate resources are very limited. The response from outside agencies and jurisdictions was almost overwhelming. When the outside resources started arriving without some form of control, problems began to surface. Many resources were staged, making it easy to control them. Difficulty arose when no communications were available and incoming resources took it upon themselves to assume responsibility. Resources at the incident included: 27 ambulances; 25 engine companies; 125 police units; national guardsmen; the Red Cross, including a helicopter; the Salvation Army; and unnumbered pieces of heavy equipment including backhoes, front loaders, cranes, dump trucks and tractors.

A large kitchen and rest area was set up at the West Hills College playing field for the homeless residents of Coalinga. One incalcuable resource in this community is the bond that its residents had before the earthquake struck. Most of the citizen volunteers knew of special talents that a neighbor might have, such as a backhoe operator or dump truck driver. Some citizens had prior fire fighting or medical service experience. The close bond allowed the people to perform tasks for each other that might not have been done otherwise.

Twenty minutes after the earthquake struck, the incident commander received a report of a chemical spill in the West Hills College chemistry lab. Standing with him in the command post was a member of a hazardous incident team from one of the local oil companies. The hazardous incident team was dispatched.

One hour later, a similar spill at the high school was reported and another team from another oil company contained this spill. A third spill was discovered in a collapsed building that housed a dry-cleaning business downtown. An engine company from staging secured this site but cleanup was delayed due to the collapse. A hazardous incident team was called to this location to measure the toxicity level in the underground tanks of solvents and to seal the tanks.

The California Department of Fish and Came was put in charge of all subsequent spills.

Initially the electricity went off and it was believed to be off throughout the community. However, when two fires were started by electric stoves and fire alarms simultaneously sounded elsewhere in the community, it was conjectured that the power might have been turned on prematurely.

The Coalinga earthquake was a thrust fault movement (colliding land masses) that originated 30,000 feet below the earth’s surface. The epicenter of the quake was just 5 miles northeast of the city.

The May 2 quake measured 6.5 on the Richter scale. The Richter scale, used to gauge the destructive force of an earthquake, is a measure of ground motion as recorded on seismographs. Every increase of one number means a tenfold increase in magnitude. That is to say, a 6.5 earthquake is 10 times stronger than a 5.5 reading. The numerous aftershocks felt in Coalinga in the days following the initial quake were in the 4.5 range. Though strong, the 4.5 aftershocks were 100 times less destructive than the initial 6.5 shock. Seismologists were unaware of the fault from which this earthquake originated. This thrust fault was created 60 million years ago when the Pacific Ocean plate (earth’s crust) thrusted its edge beneath the edge of the North American plate along what is now the California coast. The result is due to be more earthquakes in California.

Coalinga owns and maintains its own natural gas system, with Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) furnishing the natural gas to the community. City workers were dispatched to the valving system north of town to shut off the gas after citizens started reporting the smell of natural gas in the streets. The gas was shut off 20 minutes into the incident, and a PG&E representative responded by helicopter from Fresno to check the shutoff. There were no reported fires started by natural gas.

Two hours into the incident, the public information officer organized the media personnel, who were randomly interviewing fire fighters and rescue workers trying to perform their jobs, and gave tours of the city each hour. This greatly reduced the problems created by newsmen and camera crews.

There are 2500 oil wells with accompanying storage tanks surrounding Coalinga. It was feared at first that some of these sites might catch fire. Although some of the tanks spilled, none caught fire. There were a few small grass fires around town, which were extinguished by the West Side Fire Department, but none reached any of the oil wells.

Lessons to be learned

Preplanning between agencies before a major incident is imperative. Every agency involved in this incident performed superbly within the scope of its responsibility. However, problems arose when agencies assumed certain responsibilities and did not communicate with other agencies about those responsibilities, creating duplications of effort for some agencies and conflicts of authority for others.

Problems also arose when the perimeter of the incident was not secured. Resources assumed roles on the incident without official direction. Perimeter control was initiated 2 1/2 hours after the incident began by the sheriff’s office and the highway patrol.

Another consideration in an incident of this magnitude is the welfare of families of those carrying out emergency services. Emergency services should consider arrangements that quickly get word to the workers about their families’ welfare.

The experience CDF has had with handling command of major wildland fires proved invaluable. Members of the CDF worked in many parts of the incident as fire command officers, staging managers, planning and documentation officers, logistics officers and other support, command and tactical functions. All of these support activities point up the need to create defined support responsibilities for incoming personnel and resources. We all tend to suffer from the “candle moth syndrome ” and wish to become an active member of the emergency rather than support those already engaged in emergency activities.