Operation Kitty Hawk

INDUSTRIAL TRAINING

Some big lessons in preparedness and mutual aid were learned in a mock drill aboard a “floating city. ”

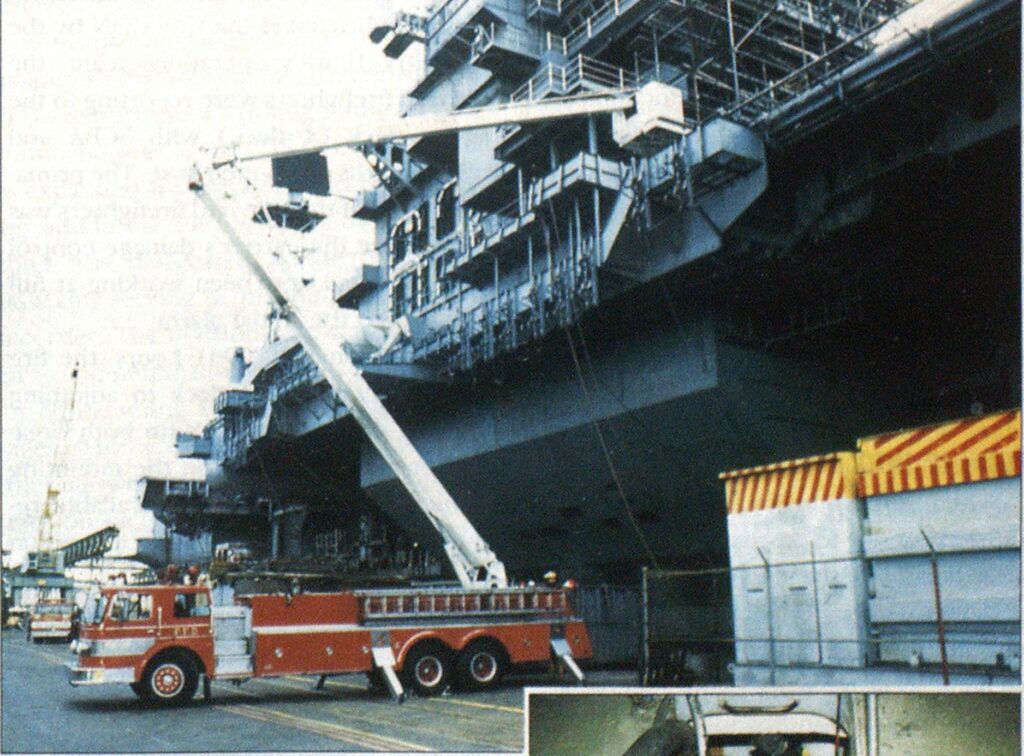

On April 23, 1988, the Philadelphia Fire Department, in cooperation with the damage control firefighting teams from the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CV 63) and the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Fire Department, held one of the most challenging fire simulations within recent departmental memory.

The stated goals of the exercise were to increase interagency participation and coopered ion, discover primary and secondary methods of combatting a major ship fire, and to become more aware of each other’s capabilities and limitations. Although no fire or smoke would actually exist during the exercise, it was agreed upon that every aspect would be as real as possible and that all three organizations would be put to a severe test with a series of unpredicted events to which they would have to react.

The USS Kitty Hawk, commissioned on April 29, 1961 in nearby Camden, New Jersey, is currently being overhauled at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard as part of the U.S. Navy’s successful Service Life Extension Program.

The carrier, located in the shipyard’s drydock #5. is truly an awesome sight for firsttime observers. With a length of 1,065 feet, a width of 273 feet, a height of almost 200 feet, and a flight deck that spans 4.1 acres, this massive structure can accommodate approximately 5,300 personnel and 85 aircraft, larger than several nearby towns, the USS Kitty Hawk contains over 600 miles of electrical cable, over 2,400 telephones, approximately four million gallons of fuel, five television channels, two radio stations, and a 77-bed hospital. Almost anything that you would expect to find in a medium-sized city can he found on the carrier.

All photos by visual communications unit of PFD.

At 0900 hours, a simulated fire began six decks below the USS Kitty Hawk’s {light deck in the emergency diesel generator compartment which spans 3 deck and 4 deck.

At that time, the ship’s nucleus fire party began attacking the fire with l ‘ -inch water lines taken ott of the carrier’s internal fire main system All damage control personnel were utilizing I S. Navy oxygen breathing apparatus tor respiratory protection.

PLUNGED INTO DARKNESS

W hen several major electrical cables shorted out due to the fire at 0925 hours, a large portion of the ship w as plunged into darkness t his aspect of the exercise was not simulated, and all firefighting crews were forced to work with emergency lighting systems and handlights.

In reacting to this situation, the fire marshal of the USS Kitty Hawk and his operations team, previously operating in the main deck’s CAS CON (Casualty Control), were forced to bring the ship’s diagrams out of the darkened command post rooms and set up on the hangar deck.

Faced with this serious problem, the fire marshal requested immediate assistance from the naval shipyard’s fire department. The entire on-duty force of the shipyard’s fire department—three 1.000-gpm pumpers, one 100-foot aerial ladder, and a communications van—responded within minutes.

While the shipyard’s on-duty fire chief was being briefed at the CAS CON by the USS Kitty Hawk’s operations team, the shipyard firelighters were reporting to the hangar deck (1 deck) with SCBA and rolled lengths of 1 1/2-inch hose. The primary function of the shipyard firefighters w as to reinforce the carrier’s damage control teams that had now been working at full speed since the initial alarm.

At approximately 0931 hours, the fire spread laterally on 3 deck to adjoining berthing compartments. With both organizations trying to contain the mounting problems, and having their available resources stretched to the limits, a decision was made to request the additional assistance of the Philadelphia Fire Department (PFD).

At 0933 hours, the fire communications center of the PFD received the official request for assistance and transmitted an upgraded full first-alarm assignment. In addition to the usual first-alarm assignment of four engines, two ladders, two battalion chiefs, a rescue squad (mobile intensive care unit), and a deputy chief, the communications center also dispatched two marine units, the air unit, a hazardous-materials task force, an additional rescue squad, and the on-duty EMS field coordinator.

With the arrival of the first-due PFD battalion chief at the CAS CON, it was learned that conditions were deteriorating rapidly: the fire had spread downwards to 4 deck via vent ducts and cableways. In addition, the battalion chief was informed that three damage-control firefighters were “down,” and would need triage and removal.

CASUALTIES, LOSS OF WATER SUPPLY, AND PHYSICAL EXHAUSTION

One of the injured firefighters was suffering from heat exhaustion and unconscious. Another unconscious victim had suffered burns to over 60% of his body, along with smoke inhalation. The third casualty, although conscious, had fallen and experienced severe neck and back injuries.

All three casualties were “live” drill participants and had been “tagged” as to their specific injuries. As prearranged, only the exercise moderator knew the location of the casualties or the extent of the injuries beforehand.

Due to the narrow passageways, steep stairwells, and poor illumination, the triage, packaging, and removal of these victims was to become a major endeavor for all three organizations.

In addition to these problems, the PFD battalion chief was informed that the ship had suffered a sudden loss of firefighting water from the on-board fire main system due to a fire pump failure.

Finally, the battalion chief observed that both the firefighting crews of the USS KittyHawk and the naval shipyard fire department were approaching the point of physical exhaustion. Forty-five minutes of stretching water lines, carrying and operating various equipment, all while utilizing breathing apparatuses for “up-close” work, had taken its toll on the early participants.

Faced with the far-reaching magnitude of the problem—a below-deck fire spreading out of control, a loss of all firefighting water to the ship, and a certain casualtyoperation to handle—a second alarm was transmitted at 0947 hours.

This second alarm brought four additional Philadelphia engine companies, one snorkel ladder company, two battalion chiefs, a third rescue squad, and the department’s communications vehicle to the scene.

An engine company was directed to the shipyard’s fire station in order to provide immediate protection for the complex in the event a real emergency was received; this unit was provided with a guide from the shipvard’s on-duty force.

INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM

The initial priority of the PFD was to set into place the fundamental elements of its Philadelphia Incident Command System (PICS).

Four major operational locations were designated immediately. The operations command post was established in the PFD’s F.100 unit, located dockside, in close proximity to the shipyard’s communications van. The tactical command post was established right alongside the Navy’s already functional joint-command post at the CAS CON, on the Kitty Hawk’s hangar deck. A forward command post was set up, with the assistance of U.S. Navy “runners” (message relayers), on 2 deck, at the approximate midship point. This critical sector was established as close to the fire zone as was practical, while ensuring a stable environment from which to operate and launch direct firefighting attacks. The fourth sector was comprised of two staging areas: one established dockside under the command of the logistics chief; the other set up on the carrier’s hangar deck under the command of a battalion chief, referred to as the fonvard staging area.

With the enormous volume of communications threatening to overload the PFD’s deputy chief working in the tactical command post at the CAS CON, he quickly expanded his support team by activating additional PICS options. A battalion chief was designated as the operations assistant, serving as planning officer and recorder. The division aide was designated as communications officer, responsible for all incoming and outgoing radio messages. The activation of these two keyroles allowed the deputy chief to concentrate on tactical considerations.

As is standard PFD procedure, PICS identification vests were issued to all key personnel, denoting their roles in the operation.

In the early moments of the operation, the two top priorities for the PFD were the treatment and removal of the three casualties and the upgrading of the lighting situation.

Under the direction of the triage coordinator, all three casualties were assessed byparamedics in the forward command post and then tagged with their triage priority.

The firefighter suffering from heat exhaustion was “revived” and then assisted up the metal stairwell to the hangar deck. Two PFD rescue squads had been able to drive onto the huge deck and set up first aid stations to accommodate incoming casualties. Once on this main deck level, the firefighter was placed on a hospital cot and wheeled to the first-aid area for follow-up treatment.

The remaining tw-o casualties had to be removed on stretchers. The firefighter with burns and smoke inhalation was given oxygen and preliminary burn treatment, and then placed in a Reeves stretcher. The casualty with neck and back injuries was fitted with a cervical collar, placed on a backboard, and then secured into a wire basket.

The removal of both of these injured firefighters up through the narrow, dimlylit stairwells proved to be a formidable task for the rescue teams. With the aid of the damage-control personnel, the chain side-railings of the stairwells were collapsed in order to provide more clearance for the difficult maneuvers. At times, the stretchers had to be angled to near vertical positions while being secured from the top with hauling ropes.

Upon reaching the awaiting rescue squads, all three casualties were removed from the ship and driven “around the block” to simulate transportation to a hospital.

Simultaneous with the casualty removal operation, efforts were being made to increase the available lighting. Portable generators were brought on board, and set up in well-ventilated areas. The generators were kept as far as possible from the communications positions so that the noise level would not impede operations.

At dockside, the logistics chief was addressing a multitude of support problems. The two foremost problems were the resupply of air to the SCBA cylinders and the restoration of firefighting water to the ship.

AIR SUPPLY

Because all firefighters involved in the exercise were actually using their air supplies, the resupply operation became critical. First-arriving units were all reporting to the staging areas carrying all their extra cylinders; however, these were being expended rapidly.

With the arrival of the PFD’s air unit and a chemical unit, prepackaged crates of full cylinders were delivered to the forward staging area. This added fifty charged cylinders to the on-board inventory.

The air unit engine company was then assigned the task of establishing a remote refilling station. Within minutes, an air supply line had been stretched from the air unit down to the forward command post on 2 deck. A manifold, enabling cylinders to be refilled three at a time, was used.

With the remote refilling station working to capacity in recharging the thirtyminute cylinders, the forward command post chief opted to place the PFD’s Scott Pak Extension System in service to provide longer staying time for the attacking suppression teams. (Air was then supplied directly from hoses of an air unit with compressor that fed through a cascade system.) The thirty-minute, self-contained air supply, as applied to the Kitty Hawk ope ration T was not practical: it was found that by the time the advancing hose teams had reached the fire zone, they had only minimal time for extinguishment activity, having to save sufficient air supply to make the return trip safely.

Shortly after the initial alarm, it became obvious that communications-or lack of it-would determine the overall success of the operation.

During this operation, the recording of team entry times became a paramount safety consideration. All advancing teams were backed up with another team on standby, at the same point of entry.

TTiis operation brought to light one of the fundamental differences in combatting a ship fire in dry dock, compared to the same fire while at sea.

At sea, a sound strategic decision might be to seal off the fire and limit the spread of heat and smoke by physical barriers; with this containment concept, auxiliary suppression systems may be activated, or firefighting teams could approach the fire from relatively controlled areas. However, with a ship undergoing dry dock renovations. large numbers of “access holes’” for construction activity may render useless any attempt to seal off the fire.

Of course, each scenario has its own set of advantages as well as disadvantages, and it became clear during the USS Kitty Haw’k operation that the PFD could utilize its air extension system and safety lines without fear of having any “trailing lines” breaching compartment integrity, or having the lines caught in closing doors.

WATER SUPPLY

With two PFD marine units arriving on location, their duties were split.

Marine 15 was assigned the task of pressurizing the dry dock manifold that would resupply firefighting system water to the carrier. During its stay in dry dock, all firefighting w-ater for the ship’s fire main is supplied from this dry dock system, which the exercise moderator had suddenly placed out of service due to a pump failure. To accomplish this task, several adaptors were required, along with shipyard personnel familiar with the proper control valves that needed to be activated.

Marine 32 anchored across from the ship’s midpoint; the task of her crew’ w’as to supply firefighting water (taken from the river) to all PFD units on board. To accomplish this goal, a five-inch supply line w-as stretched manually from the marine unit’s discharge to a large-diameter hose manifold on the carrier’s hangar deck. This feeder-line manifold supplied the PFD with four 3 1/2-inch outlets in relatively close proximity to the forward command post. This additional supplyline, when added to the first-alarm unit’s 3 1/2-inch line that was previously stretched on deck, gave the incident command team enough options to place over a dozen more attack teams in service if required.

MOVEMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

By this time, a system was in place using USS Kitty Hawk runners to assist the PFD forces in reaching their assigned positions throughout the ship. It was discovered very early in the operation that the assistance of these runners would be of critical importance if the PFD’s manpower and resources were to be truly effective. It w as an impossible task for PFD members— donned with SCBA and with only emergency or hand lighting to guide them —to find their way alone below totally unfamiliar decks. Runners, therefore, were assigned to a specific chief or unit for continuity, and remained with them throughout the operation.

Throughout the exercise, the PFD’s portable radios were of limited value. Messages could only be received from one deck to the next, and then only if the radios were not too far removed from the stairwells. To combat this major problem, the PFD’s incident command team relied on three alternative methods of communication:

- Portable radios were set up “in relay” to transfer messages back and forth.

- Where possible, full use was made of the U.S. Navy’s runners.

- The F. 100’s voice-activated phones were placed in service and stretched from the CAS CON down to the fire area.

Before the exercise took place, it was speculated by all three organizations that communications would be the number one problem to be overcome. Within a very brief period after the initial alarm was struck, it was obvious to all involved that their speculation was entirely correct: Communications, or the lack of it, would he the lynchpin governing the overall success of the exercise.

To help incoming firefighters locate their designated areas on the ship, the chief of the forward staging area had a rope stretched from the hangar deck staging area to the CAS CON. In addition, yellow, high-visibility haz-mat security tape was stretched from the staging area to the forward command post below deck. This proved to be an excellent means of eliminating directional confusion, and also served in reducing the required verbal instructions.

At approximately 1015 hours, the fire marshal of the carrier informed the PFD’s incident command team that one of the CSS Kitty Hawk damage-control firefighters was missing. A coordinated, joint search effort located this missing firefighter in a berthing compartment on .5 deck at approximately 10.55 hours. The victim was suffering second-degree burns to the hands and chest, but was able to be assisted up to the hangar deck first-aid stations.

As PFD forces were approaching depletion, a third alarm was transmitted at 1018 hours, followed by a fourth alarm at 10.50 hours.

With a fragile communications network in place, the air resupply operation running smoothly, and the casualty problem stable, the FFD incident command team turned its full capacities towards ventilating the smoke and extinguishing the remaining fire.

Exhaust fans from all three organizations were placed in service via emergency power sources. The smoke was channeled toward the large construction openings Every effort was made to direct the smoke flow away from the advancing hostteams.

TEAM CONCEPT

Strategy dictated that the hose teams descend the stairwells far enough away from the main body of fire to avoid going down through any “chimney-type” openings; once on the same level as the fire, the teams approached horizontally and engaged the fire. In the event that a horizontal approach was not feasible, a backup plan called for the hose teams to descend to the level below the fire, bypassing the intense heat and smoke, and then coming up to the fire, similar to standard high-rise strategy.

Of all the evolutions performed during the exercise, this one aspect drove home vividly the mandatory “accountability factor” that every FFD supervisor experienced during the simulation. In reacting to this hostile, completely foreign environment. every PFD unit that boarded the ship remained acutely aware of the necessity of staying together as a team. For safety’s sake, even tasks that could have normally been carried out by a single firefighter were carried out by entire units, or at the minimum, by two-man teams.

FINAL EVOLUTIONS

To add further realism to the exercise, three common pieces of shipboard metal were provided for the FFD to practice their manual cutting techniques.

Using their power saw. the members of haz-mat unit #1 easily cut through a 1/8-inch piece of aluminum. A second test called for them to cut through a 3/16-winch piece of stainless steel; although this operation was slower than the first, the saw was effective. In the final test, the saw was used to cut through a piece of 1/4-inch steel, identical to some of the bulkheads. Although blade changes were required to make a “rescue-size” hole, the saw was once again effective.

This same 1/4-inch bulkhead steel was then cut by the haz-mat unit’s burning outfit with very little difficulty, and in a much shorter time.

This “hands-on” aspect of the exercise was very beneficial to the PFD, for it pointed out some of the capabilities and limitations it would have in cutting holes for rescue, ventilation, applicator insertion. and the like.

In the final evolution of the exercise, the operating command teams decided to abandon the hoseline attack and utilize high-expansion foam to finally extinguish the fire.

This hostile, foreign environment kept every unit acutely aware of the need for staying together as a team.

Exterior compartments, approximately 12′ x 12′ x 12′, were provided for the FFD. Within a brief period, the highexpansion foam had completely flooded all the designated testing areas.

With this evolution complete, the USS Kitty Hawk’s fire marshal signaled “All out.” and the PFD placed the “fire under control” at 1101 hours.

As all the weary participants gathered on the hangar deck and dry dock areas, three obvious conclusions could be drawn immediately, without the necessity of any “formal” critique.

The first point that struck everyone was the lengthy “reflex times.” or the elapsed time from the moment an order is given until it is actually carried out.

It took a full eighteen minutes after the FFD’s initial alarm was struck out for the first PFD officer even to reach the CAS CON area on the ship. It required 26 minutes from that initial alarm to remove the first casualty from the ship, 31 minutes for the second casualty, and 37 minutes for the third.

Every aspect of the operation, whether it was stretching hoselines, setting up a smoke ejector, or simply relaying a message, was seriously affected by these extensive reflex times.

These lengthy time spans reinforced PFD’s philosophical belief in the value of “anticipating to the safe side.” PFD’s training emphasis is on developing fireground commanders that can anticipate, predict possible negative scenarios, and summon adequate assistance early.

The second factor that was obvious to all the participants was the firefighters’ stamina. Although no smoke or heat existed, this operation was extremely physical from start to finish. Tools, equipment, and hoselines all reached their final destinations by dedicated firefighters carrying the items, while donned in full running gear, and with a SCBA on their backs—if not the entire way, at least the “last leg.” This exercise reinforced the value of having a firefighting force that is in top physical condition, capable of engaging the enemy on any plateau.

The final, overwhelming impression was the acknowledgment from all the participants that there may be no worse scenario than combatting a major belowdeck fire on a ship, whether civilian or military. Certainly, such a task would be comparable to the major challenges the PFD faces periodically in handling serious high-rise fires, large-scale refinery fires, or complex haz-mat operations.

Shipboard firefighting is a very’ specialized aspect of fire protection that demands our attention, our involvement, and our highest respect.

It is frequently said that “success is a journey, not a destination.” On April 23, 1988, the Philadelphia Fire Department, along with their counterparts of the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Fire Department and the USS Kitty Hawk damage-control teams, took a giant step in that journey toward maximum interagency cooperation and achievement of mutual goals.