THE STANDARDS CRUNCH: A Fire Service Dilemma

LAWS & LEGISLATION

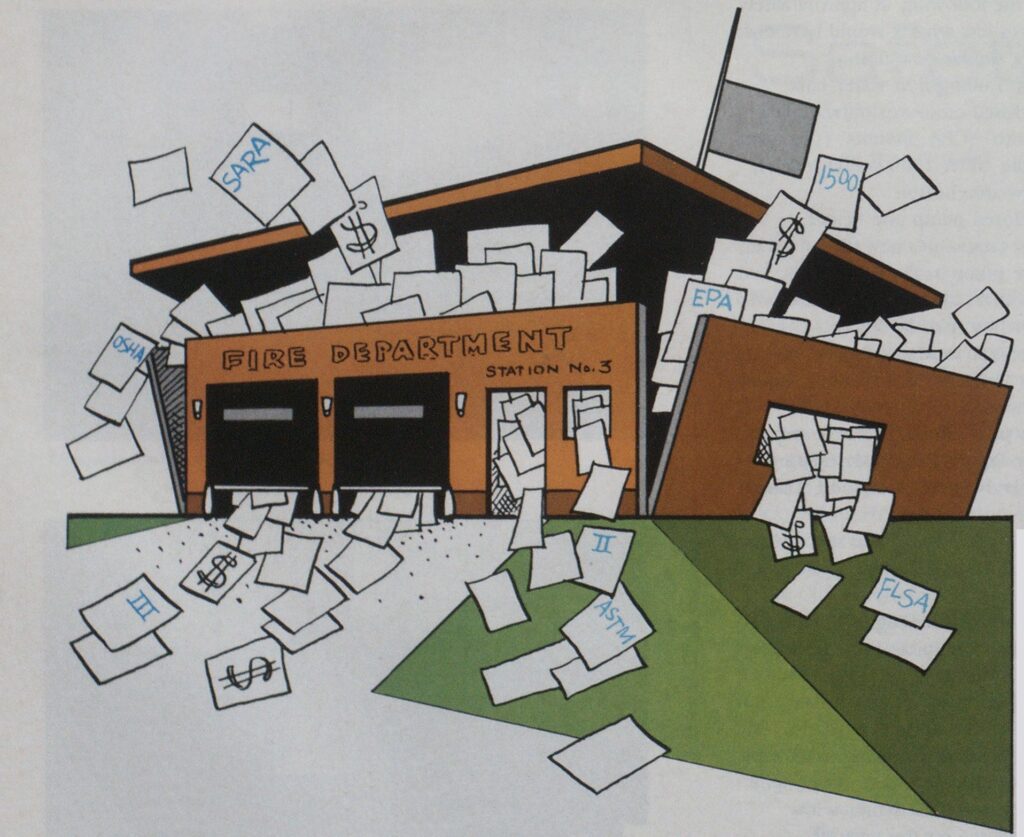

(Illustration by Arthur Arias)

Compliance with the statutes, standards, rules, and regulations imposed on the fire service exacts a toll on fire departments, big and small.

IT SEEMS THAT during the last few years the fire service has been bombarded with a myriad of so-called “mandates”—national standards, federal statutes, rules and regulations from federal, state, and local administrative agencies, and the like. The Fair Labor Standards Act, SARA Title III, OSHA hazmat regulations, Environmental Protection Agency haz-mat rules, NFPA professional certifications, NFPA 1500 health and safety standards, Federal Highway Administration licensing requirements, ASTM emergency medical service standards—the list goes on and on, ad infinitum.

Although many of the groups responsible for creating, recommending, and enforcing the “mandates” have done so with the noble intention of making the world a better place, there are nevertheless many interested parties who feel that there may be ulterior motives. Some of the rule makers, for example, are in the code-selling business, so the more codes written, the more codes sold. Likewise, rules and regulations that carry penalty provisions are somewhat self-serving, or at least self-perpetuating, when proposed and adopted by the same agencies charged with their enforcement.

Whatever the reasons for their creation, one thing is for sure: many of these “mandates” are being written in such a manner that they impose serious financial burdens on the nation’s fire departments. We may be forced to buy new equipment and/or modify all of our equipment, change our data collection system, or spend time and money to meet new training and certification requirements. But regardless of how your department is specifically affected, it’s clear that the majority of rules, regulations, and standards are being promulgated without much thought given to the financial impact—or for that matter, any impact—that they have on the fire service.

THE FAIR LABOR STANDARDS ACT

For example, how did the FLSA affect the fire service?

Adopted in 1938 by the United States Department of Labor as a means of economic recovery from the Depression, the FLSA sought to ensure a maximum number of jobs that paid a minimum livable wage. By requiring overtime pay, the FLSA created a monetary penalty for employers who did not spread their existing work among a greater number of employees. It provided an incentive to hire more people rather than require that existing staff members work more hours.

Initially, the FLSA applied only to private employers directly engaged in commerce. Government employees were added by amendments to the act in 1966 and 1974. 1966 saw the inclusion of certain groups of federal and state employees (nursing home workers, transit workers, etc.). The 1974 amendment expanded coverage to include almost all state and local government employees. However, before that amendment went into effect, the National League of Cities (NI.C) challenged its constitutionality in the case of NI.C vs. Usery. It is interesting to note how our fate can turn on closely split decisions of rule-making bodies. In a split decision, five votes to four, the Supreme Court ruled the application of FLSA to state and local governments unconstitutional.

The justices reasoned that traditional state and local government functions could not be invaded by the federal government. Where local government was acting in a proprietary function (in other words, in a “business” capacity), FLSA still applied. Because of this interpretation, a whole slew of questions arose as to what a “business” function is.

In the 1985 Garcia case, the Supreme Court took another look at the issue and decided that the “traditional government function” test was unworkable and inconsistent with the Constitution. Again by a 5-4 split decision, the court reversed its ruling in Usery and held that state and local governments must comply with the provisions of FLSA. Notice, if you will, the profound and lasting impact that the reversal of Usery had on the fire service.

The fact that one justice, Harry Andrew Blackmun, changed his mind between 1976 and 1985 cost state and local governments literally hundreds of millions and perhaps even billions of dollars. The word “perhaps” is used here because the full, nationwide cost of the Garcia decision has yet to be factually determined. Why Justice Blackmun changed his mind over a twelve-year period is irrelevant to this discussion, but that decision changed the way that we conduct “business” for a long time to come.

So, what has been the impact of FLSA on fire departments? While it was originally intended to protect the worker from employer abuse, there are still many letter opinions being issued by the Department of Ltbor regarding what is and what is not proper procedure under FLSA. It is still too early to tell what the total impact is, but we can certainly look at specific types of impact. Perhaps the most significant was that of having to pay overtime on anything over 53 hours a week or its equivalent in an adopted work cycle.

In 1987, the United States Fire Administration estimated that there are 200,000 paid firefighters in 1,800 fully paid departments nationwide who receive an average salary of S35,000 a year. From these figures we can extrapolate the following for just one hour of overtime per week:

- The average firefighter would get S 18/week additional.

- The average firefighter would get S936/year additional.

- The cost to just the 1,800 fully paid departments would be approximately S200 million annually.

What about the nondirect impacts? What was the economic loss to the fire service by paid employees no longer able to volunteer their services? What was the cost to alter the way we calculate payrolls and keep our records—the accounting systems, the computer programs, the designing and printing of forms, the changes in payroll systems? What was the cost of training necessary to familiarize ourselves with how to live with FLSA; what was the cost of the seminars, the books, the lectures? What will he the cost of litigation over FLSA as it evolves?

THE STANDARDS CRUNCH

FLSA was one of those mandates thrust upon us without a whole lot of need or reason. It was an attempt to cure a problem with a brush that was too broad.

SARA TITLE III

So we tackled FLSA. Next, SARA Title III came along, with its concomitant OSHA rules and EPA regulations. When SARA became law in 1986, it directed OSHA to develop final rules by October 1987, effective October 1988. While OSHA rules would not have applied to non-OSHA states, SARA also directed the EPA to draft rules within 90 days of OSHA’s final rule that are identical to the OSHA standard. The EPA rules, if they include firefighters within the definition of “employee,” do apply to all the states.

It was, therefore, obviously the intent of Congress when they wrote SARA to include all fire departments, EMS agencies, and fire brigades—including volunteer groups—under the regulations. While the intent of SARA was wellfounded—it was an attempt to address the serious problems of hazardous materials—as is all too often the case, it’s the way that the objectives were implemented that has caused the difficulties.

The main thrust of SARA Title III was to require industry to provide information—either lists or material safety data sheets—on acutely toxic chemicals that are involved in their businesses. Additional requirements include the creation of an emergency response plan, the use of an ICS, minimum required training on haz mats (up to 24 hours annually for some categories), physical exams and medical surveillance programs for team members, and minimum equipment standards for firefighting personnel and haz-mat team members.

While these requirements may not affect those departments that have the financial resources to deal with them, consider that many of the 35,000 fire departments in this country are small and operate on a shoestring budget. The reality is this: If we drive these small departments out of business through the costs of “mandates,” how much property will be destroyed and lives lost before something surfaces to take their place?

The costs placed on fire departments by SARA are obvious. First and foremost is the cost of program management or administration. Most industries involved in the manufacture, sale, and storage of haz mats were well aware that compliance with the Tier II requirement-stipulating that they submit chemical lists or MSDSs—would limit their liability significantly should an accidental release occur. The paperwork rolled in. How many dollars were and will be spent in developing and maintaining systems to allow for the storage and retrieval of furnished data? What about the physical space necessary to take care of volumes of MSDSs? How will volunteers find the time to take off from their full-time jobs to get the required training or the necessary physicals if they are part of a “team,” and, even more importantly, how do fiscally strapped departments pay for these items or requirements?

Creativity and proaction are two of the ways—perhaps the only ways—in which many fire departments can survive in light of some of the SARA requirements. A good example of proaction can be drawn from Delaware County, Pennsylvania, a highly industrialized area, urban in nature, that is protected by 73 small fire departments. The county’s Haz Mat Advisory Committee was established a full year before SARA took effect, so that by the time the regulations were formally instituted, the committee was able to focus on all areas regulated by SARA without delay. Furthermore, Delaware County dealt with the “mandates” creatively by designing a questionnaire that was more specific to each industrial complex within the area than a generic MSDS. Because of their lack of resources to manage additional volumes of paperwork created by SARA, the questionnaire proved to be an effective alternative. To address equipment shortages in haz-mat incident response, the Haz Mat Advisory Committee made arrangements to borrow encapsulating suits and other equipment from industry when it was needed.

Even with their proaction and creativity, Delaware County, like many other jurisdictions, still confronts the problem with the almighty dollar when it comes to protective clothing and equipment and required training. While money is available for some training, there is usually nowhere near enough to go around. To date, no funds have been made available for protective clothing or equipment mandated by federal regulations.

But, as always, we will find ways to survive despite the odds.

NFPA 1500

So we get done with SARA and along comes NFPA 1500. Not to sound like a broken record, but this again is a case in which the motive was proper (to provide for better and safer working conditions for fire service employees) but the methods were misdirected.

Not surprisingly, the issue for the most part revolves around affordability. Of the 100-plus requirements found in 1500 proper, many may not present a real financial burden for some of us; for many of us, however, much of 1500 may pose problems, even with a phase-in period. I might point out that the issue of NFPA 1500 compliance has had a considerable impact on larger departments with tight budgets as well as smaller paid departments and volunteer departments.

Research in Ventura County, California, for example, revealed only four significant areas in which the department did not already comply with 1500, but those four areas carried a cost of over S 400,000. Of course, that figure reflects only these items that apply to the text in the strictest sense; there are some unknowns, such as whether or not the estimated S200 per person will really be sufficient for the medical examinations that are required.

THE STANDARDS CRUNCH

Even the best research can’t account for the cost of items currently listed in 150()’s appendix that may well work their way into the text some day. Consider item A—6-2.1, which recommends that the minimum acceptable level of company staffing be four personnel per engine and four per ladder in normalrisk areas, and five personnel per engine and six per ladder in high-risk areas. While four-person companies may be acceptable for some departments, there are many more to whom it is financially unacceptable! In Ventura County Fire District, projected figures in additional costs to add one member to each of our engines is approximately S4 million.

1 can guarantee you that the governing bodies of many fire departments already in tenuous financial positions would put another person on each engine if they had to, but they would do it by reducing other services within the department, probably by eliminating one or more response units.

While A-6-2.1 is not an issue now, it is not unlikely that labor will continue to lobby and work the committee process until the recommendation is put into text and thereby becomes a requirement. What do you think it will cost your department?

The preface to 1500 reinforces the belief that the document is well-intentioned. The writers of 1500 speak in terms of trying to compensate for industrial documents that really don’t apply to the fire service; in terms of trying to cover departments that aren’t covered by OSHA rules; in terms of providing a “framework” for a health and safetyprogram. But what one finds beyond the preface, in the text, is not a framework but a completed structure—something that not only tells a department where they need to go, but how they must travel in order to get there.

Perhaps the objection to this contradiction was best summed up by representatives from the Washington State Fire Chiefs Association in an address to the NFPA 1500 committee in San Diego, California last fall. The basic drift of the chiefs’ address was that it’s perfectly acceptable for the NFPA to set goals and objectives that are desirable for the fire service to obtain, but that they ought to leave the means and methods of getting there to the governing bodies and administrators of the respective agencies.

What bothers many fire service officials more than anything else is that NFPA 1500 committee members, admittedly, have ignored the document’s financial impact on the fire service. At no time during committee deliberations was the issue even considered. As one committee member said, “There is no price tag on safety.” While fine as a philosophical concept, it is a wee bit naive as a statement of practicality.

Somewhere in all these management courses we take is a theory of “risk management” that has something to do with weighing the cost of eliminating a risk with the magnitude of the risk itself. Many fail to see where any of that weighing went on within 1500.

It should be the fire chiefs intention to try to do everything he can to comply with 1500 as expeditiously as possible. If there are provisions that can’t be complied with, then he is left with one of two options:

- adopting 1500 and simply not complying with some parts; or

- leaving 1500 out specifically when your jurisdiction adopts the NFPA codes.

These options may not eliminate liability, though, as will be discussed shortly.

Even those departments that do not adopt NFPA 1500 will wind up negotiating over its provisions with its respective bargaining units, for the IAFF has established, as a national goal, total compliance with 1500 of all fire departments. What has happened is that NFPA has entered the labor relations field, whether it intended to or not.

To summarize the significant aspects concerning standards and their impacts:

- It is not necessarily any one standard that impacts, but the cumulative effect of all the standards that we have to deal with.

- Very little negative comment can be made about any of the standards that are published, at least in regard to what they attempt to get us to do. It is simply that chiefs with financial concerns and responsibilities would prefer to deal with safety in a manner consistent with the department’s needs.

- The “broad brush technique” of many standards appears to be punishing some departments that have made diligent efforts to keep a clean house while providing for their community, in order to bring into line some departments that may have been derelict in their responsibilities.

- Because they should believe in the standard-making process, chiefs should encourage others to comply as much as possible with the standards that are being promulgated.

It is hoped that we don’t “standard” ourselves out of business—that the rules and regulations don’t become so plentiful, so expensive, and so unrealistic that the fire service becomes a prime target for governing bodies to look at privatizing.

It should be noted that this article has only mentioned a few of the “mandates” that we have recently come to deal with —there are others that await us— and there are still others that have loomed, but have apparently failed. Among this lot is the ASTM standard on EMS. Why were we given another EMS standard, and how much would it have cost? Then there was the requirement being proposed by the Federal Highway Administration that would have required special licenses for all personnel who drive fire apparatus. The estimated cost of that mandate was astronomical: for the state of New York alone, it would have been approximately S54 million. Fortunately, the U.S. Department of Transportation decided to exempt fire department personnel (at least for now), but rest assured it will be back!

LIABILITY

What about the legal liabilities that are inherent in trying to cope with standards, and what can chiefs do about them? Quite frankly, other than complete compliance in the use of each standard, there isn’t much that you can do to avoid liability, and it doesn’t appear to make a difference anymore whether a standard is consensus or mandatory. The very existence of the standard allows it to be argued that any equipment or operating procedure that does not comply with the standard is unsafe or substandard.

While many departments are concerned with their ability to implement the requirements of NFPA 1500, the 1500 committee has consistently tried to minimize their concerns by referencing Sec. 1-3.1, which permits an entity to establish a phase-in schedule for implementation. It is this very decision by the NFPA 1500 committee—to leave the choice of implementation schedules to the individual states or localities— that should serve to intensify our concern over liability; since the standard does not specify time frames for reasonable compliance with various requirements, there remains nothing to mitigate liability exposure.

It is obvious that the mandate crunch comes very close to putting fire chiefs in a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” posture. Taking a given “mandate”—be it rule, requirement, or standard—a chief basically has four choices. For purposes of analysis, consider NFPA 1500.

First, a chief can ignore the standard and do nothing. This obviously is an unwise decision and may border upon gross negligence in failing to take note of the standard simply because you don’t like it or don’t agree with it.

J. Gordon Routley, assistant to the chief of the Phoenix, Arizona Fire Department, in an article in the Fall ’87 issue of IAFC Connections, referred to this as being a “conscientious objector” to the standard, and he was absolutely correct when he said that such a position was not a wise one to take when such a standard could save a firefighter’s life.

To substantiate this position, consider the mock trial that was conducted as part of the final day’s activities at the 1988 Fire Department Instructors Conference in Cincinnati. It was very effective and informative. An authentic judge presided over a case involving NFPA 1500 and an injured firefighter who was suing his company officer. The firefighter had fallen from the back step of his responding engine company apparatus and had received severe and permanently disabling injuries. The facts that NFPA 1500 had not been locally adopted and that less than one percent of the nation’s fire departments had adopted it were ruled irrelevant by the judge. The fact that NFPA 1500 exists and that all parties were aware of its requirements were deemed to he pertinent factors.

THE STANDARDS CRUNCH

Secondly, the chief can adopt the standard and implement the provisions that he wants and not implement the ones that he doesn’t want. With regard to those provisions not implemented, the liability remains as great as if he ignored the standard altogether.

Thirdly, the chief can adopt the standard and not establish a phase-in schedule. From a liability standpoint, an expectation may be created that implementation of all provisions will be immediate. An injury pinpointed to a provision not phased-in can result in liability due to that failed expectation.

Finally, he can adopt the standard and institute a phase-in schedule for adoption of the various provisions. This is probably the safest and most prudent route to follow.

One note of caution is that the phasein schedule must be realistic and must take into account such factors as budgetary restrictions and availability of personnel to work on the project, as well as political considerations. If during phase-in it is determined that certain goals cannot be obtained by the established dates, then the plan must be revised and updated. Surely, a goodfaith revision will create less chance for liability than a failure to attain implementation on given dates due to a blatant disregard for those dates.

A moment ago this article referred to a mock trial —now let’s talk real life. Several months ago the White Plains (N Y.) Fire Department rolled up on a working fire in a small, two-story house. The response called for three engines and one truck company. The first engine was manned by two firefighters. On arrival, the driver/engineer, upon observing fire in the attic, ordered the firefighter to stretch a 1 3/4-inch hoseline to the second floor and wait in the stairwell. The driver then went back to the street for additional personnel. New York OSHA subsequently filed a complaint against White Plains for allowing a firefighter to enter a hazardous area by himself and cited NFPA 1500 Section 6-3.1 as authority for the violation. White Plains argued that the area was not hazardous, as there was no smoke or fire on either the first or second floor.

It is extremely important to note here that neither New York OSHA nor White Plains had adopted NFPA 1500. Rather, it was relied upon merely because it exists! The White Plains Fire Department is currently awaiting its second appeal of New York OSHA’s ruling.

Regarding liability in general: If you can, adopt the standard in its entirety and implement immediately; if not, then develop a plan for future implementation (phase-in) of the standard. At least with a written phase-in, the prudent fire chief should be able to defend his actions as reasonable.

Safeguarding the public is not an easy task. Demands on the fire service are increasing in the light of industrial growth and production; simply put, there are more ways for people to get hurt. It’s necessary for there to be some order in all of this—the fire service needs direction and guidance. However, those agencies responsible for implementing and regulating that order must exhibit some sensitivity to the effects of their actions far down the road. They must balance principle with practicality. They must not “standard” out of business the very people who protect their homes, their families, and their businesses. They must not take the decisions out of the hands of those managers at the local levels.

Personnel must keep abreast of the changes that are affecting their fire service. Involvement, proaction, creativity, and flexibility are the keys to dealing with a complex world that gives rise to a complex matrix of rules and standards. They will not go away.