By Clint O’Connor

During a recent conversation with a wildland firefighter, it struck me: Why don’t we do a better job applying lessons learned in the realm of wildland to structural firefighting?

I grew up in a small volunteer department where the number of calls for wildland or grass fires in relation to structure fires was 10 to 1. After I graduated from high school I landed a job with the U.S. Forest Service as a seasonal wildland firefighter. The work was hard and the deployments long, but I never regretted the time spent out there in nature. It could be surmised as a two-week hiking trip for which you were paid.

I learned many things in those three summers before getting hired with a structural-only municipal fire department, only some of which includes the following:

- Fuel, weather, and topography (building or fuel layout in structural terms) have the greatest influences on fire behavior.

- Use the wind to my advantage.

- Attack the fire from below.

- Triage homes.

- Set up fire lines at natural barriers or other strategic areas.

- Pay attention to the weather, to always have a lookout in place (e.g., safety officer).

- Put water on the fire with a well-placed hose stream while avoiding excessive water use when supplies are limited.

- Stay out of the smoke when possible

- Avoid getting trapped in the path of the fire.

- Use the National Incident Command System.

- Communicate with your crew members.

- Conduct effective overhaul.

- Call mutual-aid resources early and often.

- Perform a thorough size-up before committing resources.

- Use resource staging and prohibit freelancing.

- Prioritize physical fitness.

- Know the importance of annual physical ability tests.

- Frequently engage in team-building exercises.

- Have daily briefing sessions.

- Attend annual refresher training.

- Constantly seek continuing education.

- Emphasize training.

- Complete task books that show proficiency before allowing an individual to act in a higher capacity.

- Mentor others.

- Work as a team.

- Slow down and work efficiently.

- PUT CREW SAFETY FIRST.

Although I could discuss each of these lessons learned in a novel, I will focus on only a few that I found to be strongly contested when I joined the ranks of municipal firefighting.

For years we have heard the rhetoric about “pushing fire” and always attacking from the unburned side. We have all deliberately walked past a window where a self-vented fire lapped the siding of a home. We do this so that we can make an interior attack, thus avoiding “pushing” the fire deeper into the home. We have been taught to always attack from the unburned side by placing ourselves between the rest of the house and the fire. Thanks to Underwriters Laboratories, we now know that we cannot push fire. We know that when we put the “wet stuff on the red stuff,” it tends to go out and improves conditions throughout the rest of the structure. Early water minimizes further growth and extension while we crawl through the home with near zero visibility in an attempt to locate the fire that was just starring us in the face.

During my years of wildland, I had never heard of the concept of “pushing” fire. I had also never considered fighting fire from the side of the unburned fuel (the “green”) prior to getting a handle on the fire. These wildland concepts have seemingly made their way into structural firefighting, although I have never heard anyone make the direct correlation. Now we know that it’s okay to hit the fire from outside and get it under control before putting ourselves in harm’s way.

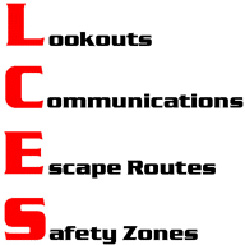

RELATED: Martinez and Schneyer on East Coast/Urban Interface Fires ‖ Wells on Applying LCES to All-Hazard Incidents ‖ Terwilliger on Unified Command at Wildfires

We are also recognizing the effects of wind-driven fires. We can trace many line-of-duty deaths back to being downwind from the fire inside the home—after windows have failed or doors have been opened. We now realize that we must use the wind to our advantage; create our own wind through positive pressure fans; or, at least, avoid getting caught downwind from the fire when these barriers have been removed, either intentionally or unintentionally.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) has put together a fantastic video series focusing on flow paths, namely caused from the orientation of ventilation openings. They studied the effects of having a low and a high opening; they found that this created a flow path that could be likened to a blow torch with temperatures that could exceed 1,500°F. Their ultimate recommendation was to attack the fire from “downhill” to avoid getting caught as it moves upward toward the exhaust vent. They were also able to show that the simple difference between a downstairs door or window and an upstairs vent hole could create a wind inside the home up to 18 mph in the flow path. In wildland terms, “topography” matters both inside and outside of the home.

Perhaps one of the most significant lessons we can take from wildland is the importance of always having a safety officer, known as the “lookout” in wildland. In my experience, safety officer is one of the last roles to be filled on the fireground. This critical position (that is typically underappreciated) is responsible for keeping an eye on the whole scene and reporting changes back to the incident commander (IC). They are also responsible for stopping unsafe practices and performing continual 360° size-ups to monitor conditions on all sides of the building. He is the one person who is not task oriented and is able to keep his eyes on the big picture without getting tunnel vision. While the IC attempts to keep the scene organized, he counts on the safety officer to give him feedback whenever a change of conditions occurs. This one person may save the lives of many without ever putting on a self-contained breathing apparatus. Similarly, the wildland lookout can ensure the safety of an entire crew without ever touching a hand tool, hoseline, or chainsaw.

Similar to the structural firefighting “16 Life Safety Initiatives,” there is the “10 Standard Firefighting Orders” and “18 Watch Out Situations” that exist in the realm of wildland. These, however, were adopted in 1957, while the 16 initiatives came along in 2004. Additionally, these wildland standard orders have been better reinforced and are frequently discussed at every level of the organization.

As I mentioned, a novel could be written on the lessons that could be learned from wildland firefighting. As a profession, we should take a closer look at our personnel who are out there on the fire line and apply best practices that are applicable in their setting, as well as ours.

Eighteen Watch-Out Situations

1. Fire not scouted and sized up.

2. In country you cannot see in daylight.

3. Safety zones and escape routes are not identified.

4. You are unfamiliar with weather and local factors influencing fire behavior.

5. You are uninformed on strategy, tactics, and hazards.

6. Your instructions and assignments are not clear.

7. You have no communication link with your crew members or supervisor.

8. Personnel are constructing line without a safe anchor point.

9. Crews are building fireline downhill with fire below.

10. Crews are attempting a frontal assault on fire.

11. There’s Unburned fuel between you and fire.

12. You cannot see or are in contact with someone who can see the main fire.

13. You are on a hillside where rolling material can ignite fuel below.

14. The weather is becoming hotter and drier.

15. Wind increases and/or changes direction.

16. You are getting frequent spot fires across line.

17. The terrain and fuels make escape to safety zones difficult.

18. You are taking a nap near the fireline.

10 Standard Firefighting Orders

Fire Behavior

1. Be informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts.

2. Know what your fire is doing at all times.

3. Base all of your actions on current and expected behavior of the fire.

Fireline Safety

4. Identify escape routes and safety zones and make them known to crews.

5. Post lookouts when there is possible danger.

6. Be alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively.

Organizational Control

7. Maintain prompt communications with your forces, your supervisor, and other adjoining forces.

8. Give clear instructions and be sure they are understood.

9. Maintain control of your forces at all times.

If 1-9 are considered, then…

10. Fight fire aggressively, having provided for safety first.

References

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. (2014). Understanding the modern fire environment. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISJuQfcj62A.

International Association of Fire Chiefs and the National Fire Protection Association. (2012). Chief officer: Principles and practice. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

National Park Service. (2016). Fire and aviation management. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/fire/wildland-fire/safety/for-employees/firefighting-orders.cfm.

Underwriters Laboratories. (2013). Innovating fire attack tactics. Retrieved from http://newscience.ul.com/wp-content/themes/newscience/library/documents/fire-safety/NS_FS_Article_Fire_Attack_Tactics.pdf.

Clint O’Connor is an engineer/acting lieutenant with Cheyenne (WY) Fire & Rescue.

Clint O’Connor is an engineer/acting lieutenant with Cheyenne (WY) Fire & Rescue.