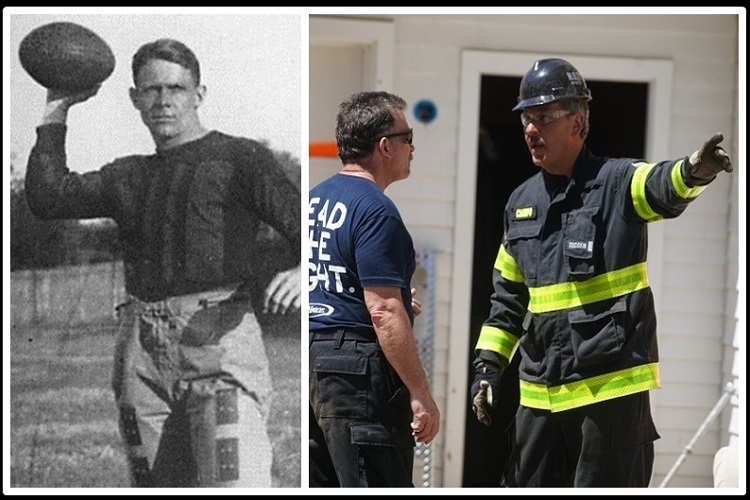

Right side photo by Tim Olk.

By Martin J. Rita

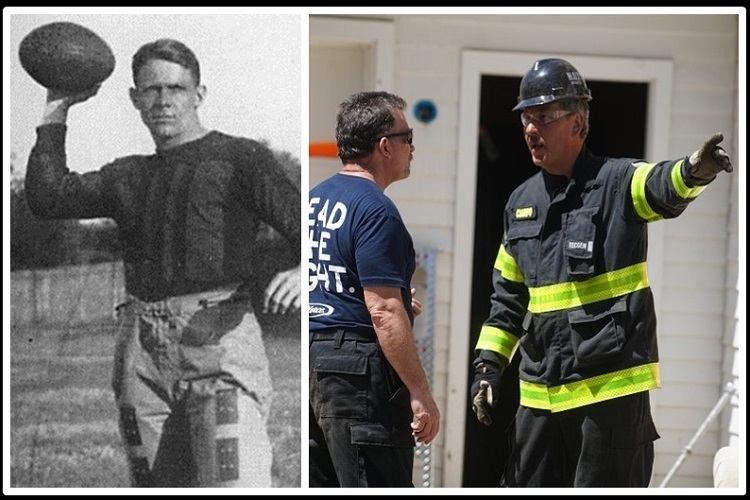

The role of the company officer is the single most important role in the fire service. Anyone can be promoted to be a company officer, but only a select few will go on to be successful ones. A successful company officer can always be compared to the position of quarterback in the National Football League (NFL); there are many that have played the position, but only a select few put it all together to become great. Both positions require the ability to multitask and to “audible” when under pressure. To achieve success, both must rely on communication, education/training, “live game experience,” and must exude a confidence that allows them not only to believe in their own success but to establish trust with their crew/team.

In a matter of seconds, both the quarterback and the company officer must be able to process a multitude of potential problems, develop/implement a plan to mitigate them, and keep their crews out of any unnecessary danger.

There are hundreds of extremely talented fire officers who have broken down thousands of ways to achieve success as a company officer, and by no means does this article take away from any of their interpretations. Just like the emergencies we deal with every day, fire service leadership is very complex, similar to the dynamics of the game of football. The different perspectives and opinions of successful fire officers help to shape those dynamics.

I recently stumbled on an article by a sports columnist that discusses what he believed to be the essential attributes of a successful quarterback in the NFL. As I read through it, I could not help but notice the extreme similarities to the position of quarterback and the role of the fireground company officer.

Good quarterbacks and officers share similar acuities and abilities. A fireground audible is very similar to one called at the line of scrimmage by a quarterback. It requires the ability to think on your feet as well as a heightened sense of situational awareness based on the extent of the emergency. Quarterbacks need to interpret what the defense is giving them before selecting the play they will run. Often, fire emergencies present like defenses and show a variety of signs and symptoms that should influence adjustments made on the fireground.

For example, a routine tactic for a fire officer is to order a 200-foot 1¾-inch preconnected line through the front door of a residential structure. Often, this tactic can be successful and takes minimal thought, but does the company officer have the ability to audible when needed? Does he have a plan B, C, or even D? If not, he should!

Following are some aspects of fireground command knowledge required from company officers:

- Location. One of the most important aspects of a 360° degree walk-around is attempting to locate the seat/location of the fire and to rule out if there is a basement. ALWAYS CHECK LOW BEFORE YOU CHECK HIGH! Look through windows, look for smoke/soot staining around window frames, and if there is any turbulence of smoke. Does the building offer rear access? Are there victims? The company officer may need to “call an audible” to lead out to the rear/Charlie sector to make entry down exterior basement stairs or through a walkout sliding glass door.

- Fire Load. An educated fire officer needs to know when to audible to different size lines and tactics to mitigate heavy fire load and fast fire extension to other attached and unattached exposures. Knowing his crew size/ability and equipment capability aids in this decision making.

- Commercial vs. Residential. Often, when problems occur on commercial building fires, it is because of the fire officer taking a “residential approach.” Commercial buildings are large, full of mixed fire loads, and built to collapse with metal truss roof construction. The front door may NOT be the best option. Even in large square-foot buildings, the second engine, battalion chief car, or other arriving apparatus can complete a 360° drive-around. Find the closest and most direct entrance route to the fire.

Also, the company officer must NOT do the following:

- Advance further than 175 feet from any egress point. (No more than four 50-foot lengths and 25 feet for exterior lead-out.)

- Turn off the sprinkler system until there are multiple reports that the fire is under control.

- “Overventilate” a commercial building that is absent a sprinkler system. Large bay doors and skylights can cause an unchecked fire to intensify much quicker.

A good company officer will adjust to different variables on the fireground such as crew size/ability, apparatus type, building style, extent of fire involvement, possible rescue, and so on. A fire officer—like a quarterback—needs to keep his head on a swivel. In a matter of seconds, they must process all sights, smells, and sounds on the fireground; determine an action plan; and execute it.

Any good fire officer needs to know not only the strengths and weaknesses of his own crew but the strengths and weaknesses of his opponent, this case being, the science of fire. To properly prepare for an opponent, you need to know how it is built; how to dismantle it; and, most importantly, how it behaves within a structure.

Do they know the difference in color, temperature, and velocity of smoke? Are they educated on modern day fire dynamics, flow paths, and ventilation limited fire conditions? Do they train with their first-due companies on coordinated fire attack (suppression, ventilation, and search execution as a timed and coordinated functional unit)? Modern day combustibles and lightweight construction have changed tactical decision making on the fireground. It is important now more than ever for fire officers to educate themselves so they understand the game and recognize “defensive tendencies.”

A successful officer will never stop evaluating himself for personal improvement. He will constantly ask questions, seek mentor advice, review past incidents, take classes, and be their harshest critic. The success of an officer comes down to his attention to detail. Each detail studied and learned through the experience of mistakes. The difference between success and mediocrity is the ability to learn from past mistakes and the ability to improve on them. Like football, firefighting is also a “game of inches” in that each detail/inch can very quickly “make up a yard,” and that yard can ultimately make or break the success of your incident. Let’s take a look at some of those “inches.”

Apparatus placement. Even before arriving on scene, a successful fire officer should be thinking about a multitude of things, including the following:

- The time of day (increases chances of rescue).

- Weather (delays, wind, and so on).

- Types of buildings in relation to the address in the first-due district (residential, commercial, industrial, and so on).

- Water supply (locations, main size, and so on).

- Crew size/ability (auto/mutual-aid response crew and equipment).

- Dispatch and communications (multiple callers, “911 caller across from,” and so on).

On-scene/Report of conditions.

- Direction of travel/dead-end streets. Not all departments announce their direction of travel, but this can be very useful to the other responding units to the scene (the second engine can back down or lay forward, use alleys, and so on).

- Occupancy type, number of stories (try to obtain three sides).

- Location and extent of fire conditions. For example:

o Nothing showing.

o Light smoke or smoke showing.

o Heavy smoke/fire or “working fire.” Don’t get caught up on an over analytical size-up of the smoke. Simply, you have smoke showing or you have a working fire.

o Defensive fire conditions. Don’t be afraid to announce a defensive condition when it is seen. Responding officers and crews should change their tactical thinking to defensive so they can make decisions (multiple hydrants, aerial operations, and so on).

o Announce an initial strategy/a tactic.

o Announce a tactical/fireground channel.

o Announce point of contact or command number. For example: “Engine 2233 is northbound on a small two-story residential with a working fire. We have heavy smoke from the rear/Charlie side. Engine 2233 will be “offensive”/“interior.” Switch all incoming companies to Red Fireground, and Engine 2233 will be Command.”

Initial strategy/tactic. Absent an initial response policy, a sound fire officer should assign his first-due truck and second engine to a task, a location, and an objective (i.e., “Truck 2804, take Alpha, split for ventilation and search,” Engine 2323, assist 2753 with a water supply and staffing on the initial attack line.”)

- Complete 360° walk-around.

- Follow-up 360° report (announce any change in initial strategy based on findings).

Tactical objectives (RECEO VS).

- Rescue. All clear/primary search for victims is ALWAYS number one.

- Exposures. Knock down any potential threat of fire impingement of adjacent structures.

-

Confinement. Locate the seat or original location of the fire and minimize any further damage to property.

-

Extinguishment. The most effective method of extinguishment is to locate the seat of the fire with a strategic and aggressive advancement of hand lines to the interior of the structure. Attempting to extinguish a fire from the exterior of a building makes it very difficult to accomplish without further damage to property.

- Overhaul. Ensure that you have a crew for overhaul directly following initial knockdown. This eliminates the possibility of any further fire extension.

- Ventilation and search*. Ventilation and search has an asterisk because they can be implemented in multiple orders of RECEO. As many of you know, the fire service uses acronyms and templates that attempt to simplify the complex decision making of a company officer, but nothing is more important than the ability to make adjustments during the incident.

Communication. You must communicate to your crews the following:

- Water supply (delays or report of positive water).

- Two-in/two-out is established (or not).

- All clear (primary search) is complete.

- Secondary search completed.

- Fire contained, “knocked,” or under control.

- Conditions–Action–Needs (CANs) and Personnel Accountability Reports (PARs). Officers are excellent at communicating their conditions and actions, but they have a difficult time orchestrating what they NEED. Previously serving in the role of deputy chief and incident command instructor, the most important piece of information to Command is what else the company officer needs to be successful. Command is nothing more than a “go-to” for the company officer, i.e., “Command, be advised the fire is knocked, we still have moderate heat conditions but improving with ventilation, we are hitting hot spots and performing overhaul. We need two fresh crews for overhaul to the first floor, kitchen area and we are PAR.” A PAR is used to quickly communicate to Command that your crew or multiple crews assigned to your sector/division/group are all accounted for under your supervision.

Tune in tomorrow for Part 2 of this article.

Martin J. Rita is an engineer/acting officer for the Midlothian (IL) Fire Department (MFD). He has also been the MFD’s training officer since 2011. Rita has been an instructor for the Posen (IL) Fire Academy, a certified hazard zone blue card incident command training instructor, a member of the MABAS 22 training committee, and a candidate/cadet program coordinator with a local Illinois high school. Rita is working toward achieving chief fire officer certification and a master’s degree.

Martin J. Rita is an engineer/acting officer for the Midlothian (IL) Fire Department (MFD). He has also been the MFD’s training officer since 2011. Rita has been an instructor for the Posen (IL) Fire Academy, a certified hazard zone blue card incident command training instructor, a member of the MABAS 22 training committee, and a candidate/cadet program coordinator with a local Illinois high school. Rita is working toward achieving chief fire officer certification and a master’s degree.