By Craig Nelson and Dane Carley

In such a complex, fast-changing world, a reluctance to simplify seems counterproductive. We live and work in a complicated world. We also know that complex, complicated environs are ripe with opportunities for mistakes because complicated environments are difficult to understand, leading to a lack of situational awareness. So, simplifying reduces the chance for error. Or, does it? A higher reliability organization (HRO) simplifies reluctantly. Why? Because, an HRO realizes that simplification means generalizing, which contributes to complacency and reduced situational awareness.

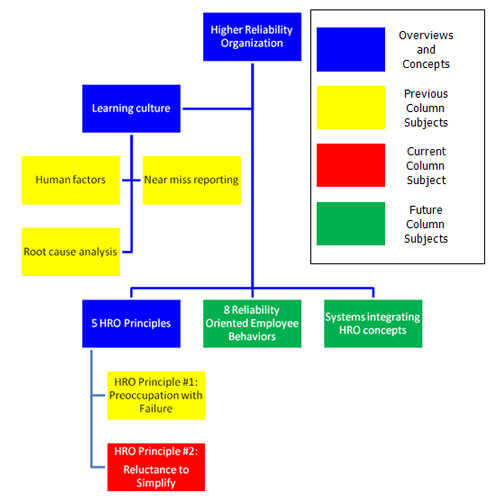

Where We’ve Been

Our last discussion, as illustrated below, centered on HRO principle #1: a preoccupation with failure, which is important because an organization focusing on its failures is better prepared to deal with problems in the future. Remember from the last article that a routine is only a solution to a previous problem that may not solve a future problem.

|

A routine is only a solution to a previous problem that may not solve a future problem. |

Where We Are–Principle #2: A Reluctance To Simplify.

We move on this month with HRO principle #2: a reluctance to simplify.

Simplifying tasks can mean increasing unfamiliarity. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007, p. 39) write, “… it is impossible to manage any organization solely by means of mindless control systems that depend on rules, plans, routines, stable categories, and fixed criteria for correct performance.” Thus, a reluctance to simplify means

- Recognizing that routine limits exploration.

- Recognizing that creating general labels and categories limits understanding.

- Challenging the status quo with constructive conflict.

An example of recognizing routine that limits exploration involves some of our regular equipment checks. We check our medical bags daily, which leads to a common simplification of placing ties on zippers of compartments used less often; if the tie is not broken, then the compartment is ready. This obviously increases our daily productivity, but the routine limits exploration. We begin losing our situational awareness as we become less familiar with what is in each compartment of the medical bags.

A fire department reluctant to simplify finds a balance between daily efficiency and providing effective services by

- Encouraging crews to use ties on less-used compartments for daily checks.

- Requiring crews to take the ties off on a regular basis (e.g., weekly) to maintain an awareness of what is in the compartment and explore their equipment and its uses.

- Challenging crews reluctant to check the compartments regularly by explaining the importance of being familiar with their surroundings.

It is important to recognize that creating labels and categories limits understanding. That is because generalization, especially when used on emergency scenes, can lead to reduced situational awareness and confusion. This problem is magnified at scenes with more than one agency or department. Training with checklists during interagency events is important to ensure words mean the same thing to everyone. However, it is important to avoid becoming over-reliant on checklists.

Asking “Why?” is a simple way to remain reluctant to simplify; it develops constructive conflict, which is fundamental to simplifying for the right reasons. Asking, “Why do we do it this way?” and receiving, “Because that is how we’ve always done it,” for an answer is not sufficient and should raise a warning flag. Instead, the answer should be, “because the way we do it is safer, more efficient, or more effective.” Basically, there simply needs to be a good reason for why something is done a certain way. As an example, imagine this conversation:

Son: “What is the best way to cook a roast, Mom?”

Mom: “You start by cutting both ends off of the roast for the best results.”

Son: “Why do you cut both ends off of the roast?”

Mom: “Because Grandma always did.”

Son asks Grandma: “Why do you always cut both ends off of the roast? Does it make it better?”

Grandma: “No, I just don’t have a pan big enough to fit the roast without cutting the ends off.”

This shows why asking “Why” is so important to improving a fire department’s operations in a humorous scenario. However, grandma does not operate in a life-safety environment, so as ridiculous as the previous conversation sounds, it illustrates that it is even more critical for us in the fire service to use constructive but positive criticism in a constant effort to improve. A diverse employee pool also improves this situation because various backgrounds, education, training, and experience bring different “why” questions. In essence, it is avoiding the “moth to the candle” syndrome at a command and administrative level from the bottom up.

Weick and Sutcliffe (2007, p. 96) include a point-based assessment tool for fire departments interested in measuring their reluctance to simplify. Since a reluctance to simplify focuses on developing an environment conducive to asking questions, many of the items focus on a fire department’s openness. Examples of assessment criteria include the following:

- Encouraging employees to challenge the status quo.

- Skeptics with diverse backgrounds are highly valued because they have a variety of experiences, education, and backgrounds.

- Questioning is encouraged.

- Recognizing that those working on the street have the best understanding of how their departments’ policies affect operations.

(This even feels progressive for us, but we’re presenting this material because we believe it will dramatically improve the fire service profession, fire department operations, and the safety of emergency responders. This reaction shows how conditioned we are.)

Case Study

The following case study is from www.firefighternearmiss.com. The near miss report, 10-0000059, is not edited. We were not involved in this incident and do not know the department involved, so we make certain assumptions based on our fire service experience to relate the incident to the discussion above.

|

Event Description Units were dispatched to an apartment fire reported “in the area of” with no address. The Battalion Chief arrived on scene and communicated a working fire. I was the officer on the first arriving engine. We found 4 apartments with heavy fire involvement, and command advised us to hit it from the other side. Not knowing where the other side was, we changed from pulling a 3” attack line to establishing a hose lay, attacking the fire with a 1 ¾” line. Command advised we had a second crew coming in behind us. We attacked fire on the 1st floor, knocking [down] major portions of fire in the first two units. My crew advanced the line to the second floor for fire attack. During this time, the fire began to intensify. The second crew was delayed in advancing the second line to the first floor units. While completing attack on the second floor, the floor collapsed, causing me to fall into the first floor. My two firefighters, who were exiting the building, advised command of the incident. Command continued communicating over the radio. I was unable to call a Mayday because of the radio traffic. I rescued myself out of the first floor and attempted to locate my crew. Command had advised them to go get me. One went inside, and one went around the back. After not finding my crew, I found command and advised him I was out and trying to locate my crew. We exchanged words. and I called a Mayday, declaring a lost crew. There were no RIT or backup crews. I also advised command to go “defensive mode” and call for a PAR report. After several tense moments, my crew was located. There was a failure of an on-scene report advising crews of location and conditions. Failure to identify, properly state task assignments, and a failure on my part to question command on my assignment to “attack from the other side.” The first crew was aggressive making it to the second floor; I did not check to insure fire was in control prior to advancing above. Lessons Learned There was a failure to have a RIT or backup units in place to assist. A good command system should have been established from the beginning. Staging should have been established with the amount of fire we had and the building construction. There was no department review or critique of the incident. Command believed it was a lack of proper actions by the first officer. I accept my mistake and have taken action to improve my abilities. The department should have conducted an investigation and a post-incident analysis so everyone could learn from the incident. |

Discussion

1. The fire service teaches its members from day one not to question orders at an emergency scene. This is a fire service-wide cultural issue. How did this culture contribute to this event?

2. Develop a chain of errors (discussed in Tailboard Talk #4) for this event.

a. Did it lead to cultural issues that are common across many behaviors?

3. Identify at least three points a participant could have questioned in the situation to develop a better situational awareness. Discuss each of these points and how the fire service culture contributed to a lack of asking questions to develop a better situational awareness.

Possible Discussion Points

1. Points during the event when someone should have asked “Why?” or “What?”

a. When command gave orders to go “to the other side.”

b. Why is the fire intensifying?

c. Why were the two firefighters exiting the building but not the officer?

d. Why would the two firefighters separate when looking for their officer?

e. Why are we not trying to learn from this incident?

2. The root cause chain of error links may contain

a. Aggressive behavior

b. Normalization of risk

c. Insufficient communication

d. Separating crew members

e. A culture of not asking questions at an emergency scene

f. Training contributing to the culture of normalizing the links a-e above

3. Three possible points when someone could have asked why or what:

a. “What is the other side?”

b. “Is the other crew downstairs making any headway?”

c. “Why do you want us firefighters to separate and enter an obviously weakened building?”

d. However, the fire service teaches its recruits from day one to never question command. Only the IC and the safety officer have the authority to do so. This was exactly the mentality of the airline industry several decades ago. Now that their culture has changed, commercial passenger jets crash much less frequently because the culture actually encourages subordinates to ask superiors “why?” This change in culture has been a part of reducing airline accidents by 70 percent or better.

Where We Are Going

The next installment of this column discusses the third HRO principle, a sensitivity to operations. We would appreciate any feedback, thoughts, or complaints you have. Please contact us at tailboardtalk@yahoo.com .

References

Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance In an Age of Uncertainty (2nd ed. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey – Bass.

Craig Nelson (left) works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley (right) entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.

Previous Articles

- Tailboard Talk: Mistakes Even Happen to Firefighters: A Preoccupation with Failure – Fire Engineering

- Tailboard Talk: Why Do We Play the Blame Game? Let’s Turn It on Its Head!

- Tailboard Talk: Near Miss Report – Fire Engineering

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization – Fire Engineering

- Tailboard Talk: Introduction to Higher Reliability Organizations