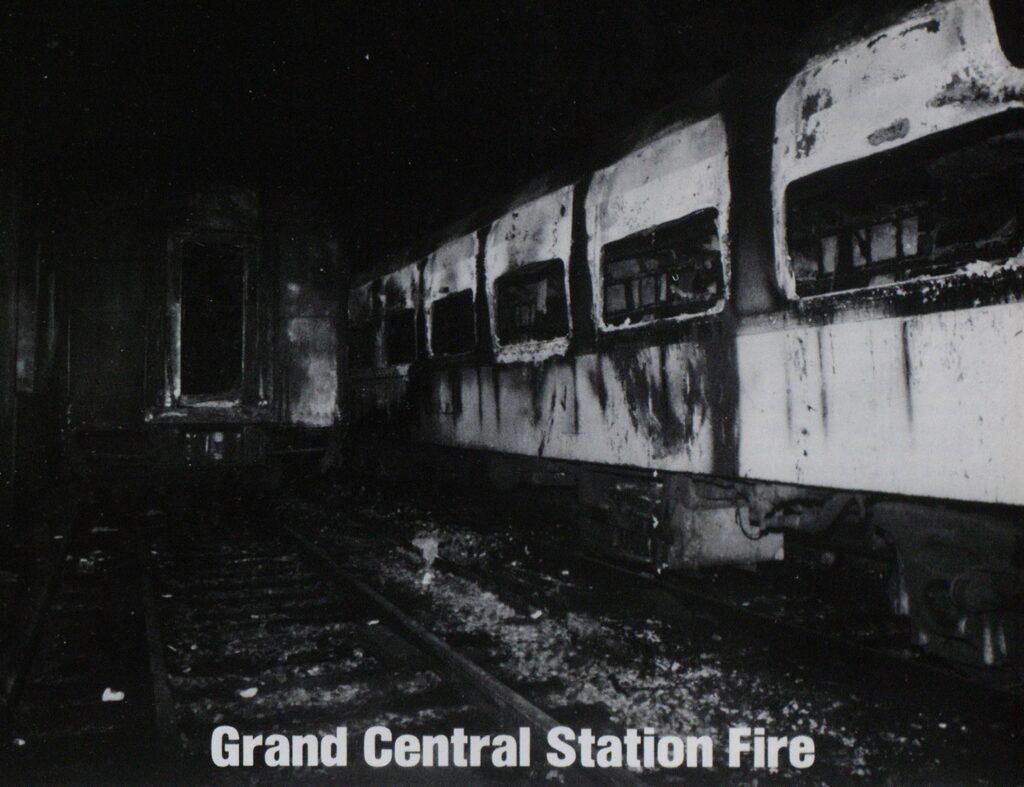

Grand Central Station Fire

Photo by Frank English

Rubbish fires on the tracks, smouldering ties, undercarriage electrical fires, smoke from track grinding or from diesel trains are usually responsible for any one of the many reports of underground rapid transit fires. In fact, in large metropolitan areas having miles of underground transportation tracks, calls for smoke coming from a grating is an everyday occurrence.

This was the type of alarm that units thought they would be responding to at 5:18 A M on August 27, 1985, when they were dispatched to a smoke condition emanating from a sidewalk grating at 47th Street and Park Avenue in New York City. In rapid succession, additional alarm locations were reported to the Manhattan communications center. Smoke was issuing from gratings in a fiveblock area surrounding Grand Central Station. An alarm for a structural fire was then received five blocks from the initial alarm location — it was Grand Central Station itself.

Grand Central Terminal rises to the height of a five-story building and has an additional seven levels more than 100 feet below grade. More than 300,000 commuters pass through this station daily. The structure also serves as a foundation for a 59-story office building. In the least busy, nighttime hours, Grand Central serves as a makeshift home for hundreds of New York City’s indigent wanderers. This unaccountable life hazard can be located anywhere. They are found on the main concourse or in any of the below-grade levels within the catacomb-type construction that routes train traffic for an area five square city blocks.

The initial alarm dispatched two engines, two ladder trucks, and a battalion chief. Before the fire was declared under control four hours later, 37 engine companies, 15 ladder units, 4 rescue units, and many special units were brought into the operation and the department increased its injury statistics by more than 100 incidents.

First-arriving units saw large volumes of smoke coming from many sidewalk gratings as they responded to the Grand Central location. They were met by transit police officers and taken below grade to the track location on the third level, 75 feet beneath the street. They reported that on Track 117, about 100 feet west of the station and into the tunnel, they could see many rail cars on fire. The responding battalion chief, receiving all this information by radio, ordered a second-alarm response.

Battalion Chief Robert L. Cantillo was informed by units within the building that one or two Metro-North railroad trains were on fire and that the fire area contained live electrical power on the tracks.

The possibility of an enormous life hazard existed. The train involved could have been carrying passengers; other operating and occupied trains might have been entering the area; other functions were being performed by railroad service personnel; and, lastly, the area was known to serve as home for many of the city’s derelicts. The extremely severe heat and smoke conditions also posed a life hazard for the operating forces themselves.

Cantillo immediately requested that power be shut down on the affected track and the two adjacent tracks. Except for extreme emergency, no firefighter was to enter the track area until the power shutdown was a confirmed and recorded fact by the fire department dispatcher. Special calls were then made for: additional rescue units; a ladder company, ordered to set up a relay for the portable communications network; the hazardous material unit, to determine possible PCB/PVC contamination; the high-rise unit for the use of their one-hour rated air cylinders for self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). The dispatcher was also requested to contact MetroNorth for information on the best access routes to the affected locations for firefighting.

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

When units arrived at Track 117’s platform, it was discovered that 18 railroad cars were heavily involved in fire. All street emergency exits in the area were ordered to be located and opened to provide vertical ventilation to the area and to help to determine the best access routes for handlines and for search and removal operations. A handie-talkie relay network was set up and added to as units probed deeper and deeper into the structure.

Photo courtesy of New York City Fire Department

Engine companies were ordered to get lines into position and to try to advance to determine and close in the perimeter of the fire. Rescue companies began a primary search in and around the involved cars.

Since Grand Central is fully equipped with a vertical and a horizontal standpipe system having outlets on all track levels, lines were taken off the outlets nearest Track 117 and excessive and arduous stretches were avoided. Because of a delay in getting the power shut down, units were withheld from advancing hose lines onto the track areas. This delay allowed the fire to continue to extend and to increase the heat and smoke conditions to a point that made routine subsurface firefighting intolerable.

There was heavy smoke throughout the third lower level, and units were reporting discovery of additional fire locations. Most of the fire condition was west of the station at a point where many tracks converge and separate. The main concern now was the possibility of other fully loaded passenger trains entering Grand Central Station, which, because of the heavy fire and smoke conditions, would result in a major disaster. Therefore, it was decided that power to all tracks on all levels was to be shut down. Further, all rolling stock and all diesel operations were ordered to cease and brake. Complete compliance with this full shutdown order took almost one hour to confirm.

Line positioning and advancement

As the initial order for power shutdown in the immediate area of Track 117 was confirmed and recorded, units began advancing toward the main body of the fire. The great distance to the fire location made it necessary to add additional lengths of hose. The routine three or four lengths of hose used for standpipe stretches were not sufficient to reach deep into the tunnel locations. Frequent relief of firefighting forces was also a must because of the debilitating effects of operating in high heat and smoke conditions, the use of full firefighting equipment, and the extensive movement of basic logistics (roll-up hose lengths, mask cylinders, etc.) for long distances through maze-like conditions in complete darkness.

Due to the reports of numerous fire locations within the tunnel, it was decided to mount a twopronged aggressive attack with handlines from each side of the fire perimeter. The main attack was launched from the south by three engine companies. They carried sufficient rolled and folded lengths of 2‘/2-inch hose through the terminal and down to the third lower level. Connections were made to the standpipe outlets closest to the scene and the handlines advanced.

The second attack was made via the sidewalk emergency exit as near as possible but decidedly north of the fire perimeter. These exit stairways down to the track level are not serviced by standpipe connections and these handlines had to be hand stretched from the pumpers located at hydrants on the street level. Coordination was the watchword. Operations were closely monitored to avoid any possibility of the danger of opposing streams.

The attack from the north proved to be very successful. The fire had been started in two trains at the northern end and spread south toward the station building. Once in place on the track area, these handlines had the most effective vantage point to extinguish the blaze.

The fire was declared under control by Chief of Department John J. O’Rourke at 9:02 A M There now continued the unfinished primary and the exhaustingly thorough secondary search.

SEARCH

Members were unable to conduct a complete primary search initially. Severe conditions in the tunnel areas forced this important function to be temporarily aborted. The physical examination of all areas involved in the fire was extremely difficult because of the damaged, incinerated condition of the interior of the rail cars. Not only were the interiors completely gutted, but the car shells had melted and collapsed onto the interior flooring, making movement and search operations dangerous and time consuming.

Since vagrants and the homeless were known to use these exact cars as shelters, a complete and intensive secondary search, including a thorough sifting of the debris, had to be conducted.

The search operation proved negative. One can only surmise what the conditions and results would have been had this fire occurred in the colder months or a few hours later in the morning rush of commuter traffic.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

By the very nature of the profession, firefighters will always be faced with unique problems (after all, we’re never called in the best of times). The magnitude and the potential for disaster in this particular incident perhaps presented more than the usual number of obstacles and strategic factors that fire forces have to overcome.

- One of the biggest problems was the intense heat and the heavy acrid, toxic products of combustion in which the firefighters had to operate. Obviously, full turnout gear, including SCBA were required at all times. Due to these adverse conditions, members quickly became exhausted and dehydrated.

As a solution to this problem, early relief must be anticipated by the incident commander and planned for. Extra alarms, mutual aid, etc., must be transmitted not more than 20 minutes into an incident such as this. Non-firefighting personnel, such as probationary school attendees, light-duty assignees, and clerical staff, may be used for changing cylinders and act as aids in any staffing function.

Canteen services responding to fires such as these should be set up and opened early, well before the fire is declared under control. They are a great source of body fluid replacement during relief periods of the manpower. The practice of holding these services in check until the overhauling phase should be examined. The recouperative benefit of their dispensing fluids to dehydrating firefighters may prevent time-lost heat exhaustion injuries.

- Added to the problem of the heat and smoke was the long distances that the lengths of hose had to be carried and stretched. The maze-like conditions through which the firefighters had to maneuver also added to the difficulty of these tactics. Stretching handlines down into narrow, unsafe, old and inadequate emergency exit stairways was also complicating routine tactical operations.

- Smoke conditions had extended throughout all levels of the terminal, to all street locations, and to the 59-story high-rise office building directly over the station. This situation added to the traffic and pedestrian control problems. Incoming units were slowed in arriving at their assigned location or staging area by the congestion problems outlined.

- Venting was a major problem. There was extremely limited vertical arteries to relieve the intense conditions below the street. There was no mechanical means to move combustion products from the occupied spaces. Grand Central depends on train movement for its routine air changing.

- Oil-covered rail ties provided poor footing to the operating forces. This, coupled with inadequate lighting, made it difficult and slow to move from one platform to another and then onto the tracks and into and around the burning trains. There was a very real possibility of members falling or being struck by moving trains.

- Firefighters were warned to be cautious of the possibility of being caught in opposing streams during the fire attack.

- The reluctance of the transit personnel to immediately shut down power remains a recurring problem. It took over one full hour to receive complete compliance with a complete power shutdown order. This factor greatly inhibited an aggressive attack on the fire scene, thereby contributing to the growing intensity of the smoke and heat conditions.

Officers commanding units or sectors should try to determine the best possible access to the fire area. This can be accomplished by consultation with the trainmaster through the dispatcher or by consulting subway emergency exit location maps that should be made up and distributed to all units well before the occurrence of any incident.

We can only reinforce the basics in this instance. Locate the fire and request that power in the defined area be turned off immediately. Additional power shutdown orders must be transmitted as soon and as often as necessary. Be aware of the fact that trains may still be moving after power shutdown (diesel trains, trains coasting into the station, etc.). Therefore, all electrical equipment should receive the same respect as if it were charged (third rails, overhead catanary wires, electrical car shoes, etc.).

Safety procedures mandate the reduction and/or elimination of carrying and using metal tools and equipment. Fog streams with rubber (insulated) tips should be used to reduce the shock hazard. Fog streams can also be used to_assist in smoke movement.

Members with signaling devices should be stationed at least 500 yards away from operations to stop train movement. Use the buddy system. No one should be permitted to work alone or without a method of communication, both audible and visual. Falls, entrapment in various devices, disorientation, air supply problems, etc., are real possibilities and extraordinary safety efforts are a must in these incidents.

- Communications were difficult. The handie-talkie units used in this department become more and more inefficient at elevated or depressed locations (high-rise, tunnels, etc.). In this situation, great horizontal distances combined with heavy, thick construction below grade in maze-like conditions rendered long-range communications ineffective.

A human relay system was set up, and members of the communication chain were positioned where they could maintain clear contact with one another. It’s vital that the integrity of this chain not be broken, even though members will want to participate in the suppression activities. Care must also be taken to keep the relay intact as these members are relieved.

Continued on page 32

continued from page 30

- A defective standpipe system caused companies to intermittently lose water pressure in their handlines throughout the operation. This was probably due to cross connecting valves being shut, air locks, or station pumps not having been started, or perhaps a combination of all three. When these problems began to surface, all engine chauffeurs were ordered to supply and augment to correct Siamese connections found at the street levels. Two units were directed to stretch handlines directly into standpipe outlets at affected track levels.

- No command station was set up by railroad personnel. Two members of the railroad police force had to lead the first-arriving companies to the fire. After that, we were unable to get any information regarding moving trains, inoperative standpipe systems, power removal, and fire pump conditions.

A special-called engine company should be assigned to act as water supply coordinator, get station pumps operating, open valves if necessary, and contact building engineers to act in direct contact for information and directions on in-house water supply systems.

Contact the trainmaster as soon as possible to get information as to the location of the fire or any special hazards or matters that we need to be aware of. The trainmaster can also direct all communications and orders from fire department command to staff functions of the rail authorities. Pump activation, valve and system manipulations, power control, etc., are only a few examples of the trainmaster’s cooperation.

Lessons reinforced

On the more positive side of the critique, there were a number of tactics used that proved quite effective in maintaining control of and mitigating the potentially disasterous incident.

- As was mentioned previously, we confronted the heat and smoke problem by calling for early and frequent reliefs and by having canteen services opened early.

- A water supply officer was assigned to coordinate and ensure an adequate water supply when the pressure began dropping.

- Many units reported to the fire scene within a short period of time, requiring good coordination of resources. A command post was set up early at the main entrance to the station to coordinate all fire activities and the activities of outside agencies (Metro-North, police, emergency medical services, etc.). A unit location board was one of the key tools at the command post as it was imperative to know the momentary, updated location of all units at all times.

- There was also good coordination of frequent relief, and extra care was taken to insure the integrity of the communication relay chain from the operation points to the command post.

- Strict radio discipline was ordered and maintained. Initially, heavy chatter masked over some vital information directed to the incident commander. All messages were transmitted through an officer assigned as communication coordinator. Messages were evaluated, recorded, and relayed to the affected commander,

- The two-pronged attack was divided into sectors. A battalion commander was placed in charge of each. His command was the equivalent of a single alarm. This kept the incident in more manageable proportions (see “The Model Incident Command System Series: Dividing the Fireground,” FIRE ENGINEERING, August 1985).

- A primary search was begun immediately and was constantly monitored and of major priority throughout the operation. The secondary search was thorough and complete, covering all areas of this immense and complicated incident scene. To insure thoroughness and effectiveness, a battalion chief was placed in charge of this operation with it being his only function.

Photo by Frank English

CONCLUSION

These type of incidents, which, unfortunately, will repeat themselves because of the many miles of underground transit facilities, require a slow but sensible aggressive attack with early and frequent reliefs up to and including overhaul. Life, of course, is the primary concern, and every precaution must be taken to safeguard not only civilian life, but the lives and well-being of emergency responders. The use of rope guidelines and sufficient lighting equipment proved a definite help to the fire forces.

There are a lot of “what ifs” in our job, and it’s impossible to say just what might have made the operation easier. Yet, a terminal the size of Grand Central Station should be equipped with:

- A permanent fire command station with a fire safety director on duty at all times. This command station should be set up on the main concourse and easily accessible to our operating forces.

- A trained firefighting brigade on duty 24 hours a day. In addition to firefighting, brigade members would test and operate all standpipes, sprinklers, and fire pumps on a regular basis. They should also be held responsible for having rubbish accumulations and other fire hazards cleared up. Records of such activities should be kept and monitored by agencies, such as the inspectional arm of the fire department, on a regular basis. This insures compliance, creates knowledgeable personnel, and gives a sense of importance to the in-place life safety equipment.

- Existing and additional emergency exits easily identified and properly lit from both directions.

- A dependable exhaust system to handle a similar type fire below grade. This exhaust system should depend on fans in emergencies, not on moving trains as is the method of providing normal air changes during routine operations.

- Larger and indestructible labels, lights, etc., on Siamese connections, indicating their locations and the area they will effectively serve.

- Upgraded standpipe system and fire pumps. Notification should be automatically transmitted to the fire department whenever the system or parts of the system are out of service for any reason.

- Antennas or hardware communication installed below level so that communications can be made more effective.

- Short wooden ladders (seven feet) present and accessible to the fire department for easy access to platforms and to the trains themselves.

- Electrical carts available to carry logistics such as one-hour cylinders, additional masks, as well as a supply of hose and other necessary equipment.

- Improved lighting in remote or dark areas that are typically found in operations similar to this.

- Supervised automatic detection systems to monitor conditions on the platforms and in the trackswitching and train-storage locations.

- A smoother, speedier, and more efficient operation procedure to handle emergency orders for power removal by emergency agencies. The needs of both agencies should be made and understood.

There should also be required specifications for future trains to be more fire resistant and for their combustion products to be less toxic. Also, areas where derelicts can be a problem should be sealed off and patroled.

On our own side, railroad terminals, tunnels, underground subways, and unusual occupancies all require pre-fire planning, drills, and discussion so that when an incident does occur, we’ll be prepared to handle it.

Since this fire, Metro-North has conducted an extensive emergency drill involving the railroad, fire department, police department, and emergency medical services. Also, the railroad has hired a fire safety director and is talking about organizing a fire brigade.

An investigation into this fire has revealed that there are over five miles of standpipes in Grand Central Station and that the incident could have been aggravated by the presence of sludge in these pipes.