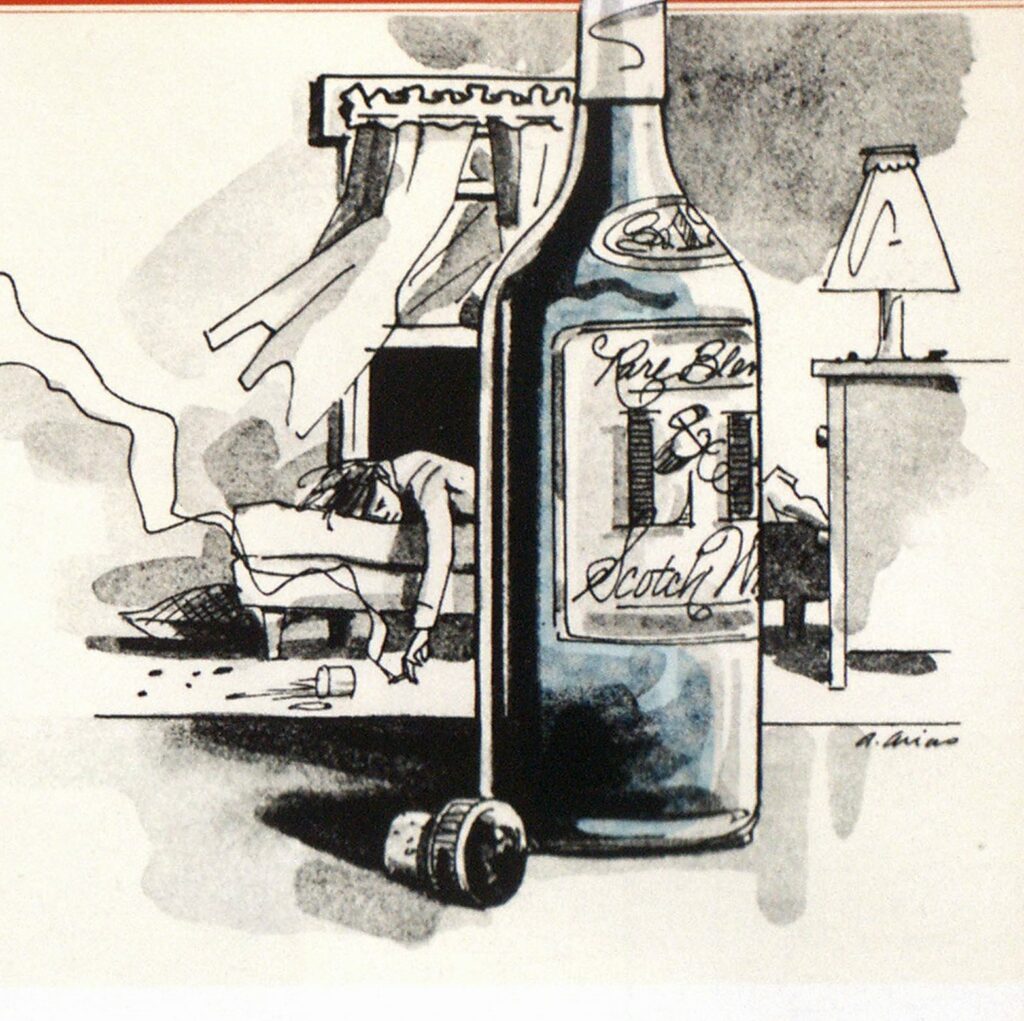

The Flammable Incendiary Liquid: BOOZE

FEATURES

ARSON INVESTIGATION

The types of fires that most readily grab our atttention and activate our investigative instincts are obviously the most dramatic ones: arsonist kills ex-wife and lover in revenge fire; pyro sets fire to fifth barn in as many weeks; twenty families homeless after suspicious fire in apartment building.

The so-called “accidental fires,” on the other hand, although they arouse our sympathy, are usually looked on as being so unintentional and so unpremeditated that they do little to captivate our interest. A smoking carelessness fire in New Jersey? Hard luck, but didn’t she know better than to smoke in bed? A cooking carelessness fire in New York? Come on now, didn’t your mother tell you not to lean over an open burner? An asphyxiation in Vermont? Now why didn’t he just turn off the burners under the pot before he went to bed?

Tragic, yes. But, during my 30odd years as a firefighter and fire investigator, the extent of my involvement was to extinguish or identify the origin and cause, and then go home.

However, after several years as a private fire and arson consultant, and after having been called in to determine the product liability on numerous potential or established lawsuits, I am becoming increasingly aware of an ominous extra dimension to fires that I had previously labeled as merely accidental.

Four years ago, an attorney approached me to represent his client in a lawsuit against a major department store. It was a sad story, but one I’d heard many times before: An elderly lady was at home smoking in the bedroom. Photographs taken after the fire showed a gentle looking grandmother-type whose upper body and back were badly scarred from burns. However, neither her face nor hair was burned, which would be expected in a fire of this kind. Her story was she had gotten off the bed, stood up, reached for a cigarette, struck a match, and her pajamas ignited.

Her attorney’s goal was to pursue a product liability lawsuit against the manufacturers/sellers of the pajamas.

As a fire marshal, my interest in a case like this would have ended the minute that I had determined the fire to be accidental.

As a self-employed fire investigator, however, my responsibility goes beyond just determining where and how a fire started. I also had to ask myself: Why?

Old lady?

Cigarette?

Bedroom?

Multi-million dollar lawsuit against a large chain store?

Interesting, but ….

I proceeded to ask the attorney several questions to elicit information that he hadn’t volunteered:

- Did his client have a history of drug and/or alcohol abuse?

- What was the drug and/or alcohol content of her blood when she was rushed to the hospital?

- What history, if any, did she have of litigations of this sort?

My suspicions were initially aroused at the absence of burn damage on the victim’s face and hair. These suspicions were augmented when the photographs of the fire scene revealed a nicely made bed covered only with sheets—the fire had occurred in January in a northeastern state where nobody sleeps without blankets.

Further probing revealed that:

- The nice, grandmotherly old lady had been hospitalized many times for drug and/or alcohol abuse.

- On the night of the fire, her blood revealed a level of alcohol to

Photo by Shelley King

- indicate that she was intoxicated.

- The pajamas in question had conveniently disappeared, preventing us from doing flammability testing on them.

- Someone had removed the blanket from her bed prior to photographing the fire scene so that any conceivable burn patterns indicating that she had passed out while smoking in bed would remain undiscovered.

- Prior to this nice, little old lady suing the department store, she had unsuccessfully tried to sue her medical doctors for malpractice.

I turned down this case.

Over the years, I have found that drug/alcohol related fires where blame is attributed to a third party for monetary gain are common, rather than rare occurrences, and that the sequence of events is usually the same:

- Intake of alcohol and/or drugs.

- Accident resulting in fire.

- Denial of intoxicated and/or drugged state.

- Product liability/medical malpractice or any other type of lawsuit to establish that something was to blame other than the person who started the fire, and to get a lot of money in the process.

Photo by Charles G. King

An interesting fact in fires of this type is that the fire victims tend to sue only large organizations (major manufacturers, hospitals, municipalities) instead of other individuals. As victims, these individuals seem to have an instinctive awareness that they may be able to generate sympathy for their case against a faceless industrial or municipal giant, but that they just might not do as well against an equally vulnerable human being.

The types of circumstances in which these cases manifest themselves are as varied as they are audacious:

In one instance, we were called to investigate a fire in which an 18year-old female died of smoke inhalation. Our client, the family of the deceased, was seeking a product liability determination, having reported that the fire was caused by a defective stove. Our on-scene fire investigation, however, revealed several interesting facts:

Continued on page 31

Continued from page 26

- Two of the on-off valves of the stove burners were “frozen” in the on position by the fire.

- The deceased had arrived home at 8 P.M.

- The fire department had responded to the alarm shortly before 10 P.M.

- Greasy hamburger residue was found on a plate in the kitchen, indicating that the victim had cooked herself some hamburgers after coming home.

- There was a functioning smoke detector outside her bedroom.

- The victim was dead in her bed when the fire department arrived.

The family’s attorney had worked out a highly libelous scenario about defective stoves, leaking gas, and “building a case” against the landlord. He chose to disregard the two activated stove burners, as well as the evidence of the burn pattern indicating that the grease-filled hamburger pan on the stove had ignited and communicated to the rear wall and cabinets above the stove.

We learned from a grieving sibling that the deceased had been a heavy drinker; that she had arrived home “drunk out of her mind”; and that “I know her. She was so drunk that she forgot to turn off the stove.”

Another interesting case involved an arson homicide. How can that possibly be alcohol contributory?

A successful businessman was discovered burned to death in his brand new car parked on the shoulder of a seldom-traveled road in eastern Pennsylvania. Within weeks of his death, his widow had filed a product liability lawsuit against the automobile manufacturer.

During my fire analysis on behalf of the car manufacturer, I discovered separate and distinct multiple points of fire origin, and burn patterns indicating the introduction of foreign combustible liquids in the car.

When this case was brought to trial, despite the highly emotional advantage of the plaintiff (being a widow with two children), the defense still won the case.

Why?

Very simple—evidence. Accidental fires do not have multiple points of origin. The jury understood this. But how does this incident relate to the alcohol contributory fires I’m discussing?

Photo by Charles G. King

Well, our case preparation for the trial revealed more interesting evidence:

- The deceased had been drinking at the local bar until it closed.

- Although he was too drunk to drive, he did drive away from the tavern at about 3 A.M.

- An autopsy of his charred remains revealed that his skull had been cracked and his jawbone broken prior to the fire.

Because the fire investigators and police department did not properly investigate the circumstances surrounding this fire, a criminal got away.

Because the coroner did not do a blood and alcohol test on the victim’s remains, important questions were never asked:

- Had the victim begun to drive home, passed out at the wheel, and then been murdered while unconscious?

- Who had motive to kill him? His wife? His business partner?

- Who broke his skull?

- Did anybody follow him when he left the bar?

- Did he get into a quarrel with anybody before he left the bar?

A perfectly solvable criminal investigation could have been aggressively pursued and the less than perfect product liability case avoided if more awareness had been brought to bear on the victim’s state of sobriety before his death.

At presstime, I was investigating a case in Florida in which a young, many-times-arrested and psychiatrically treated heroine addict is suing a car manufacturer for the. “mental anguish” he suffered when his car spontaneously ignited. A careful analysis of the fire scene and witnesses’ statements, however, revealed that:

- The car in question had been driven to an isolated area on a friend’s farm.

- Flammable liquid had been poured in the passenger compartment of the car.

- Other than the “mental anguish” suffered by the young man initiating the lawsuit, he was completely unharmed by the fire.

In addition to these obvious attempts of people trying to evade their own responsibility with regard to a fire, affixing blame for an incident can get much more complex. Consider this case:

Continued on page 33

Continued from page 31

An 18-year-old and his friends set an illegal bonfire on his parents’ property. A neighbor called the police. A one-man squad car responded and perceived that some of the local kids had begun a weenie roast and drank too much beer. The police officer, who knew the 18-year-old on whose property this was occurring, told him to put out the fire and cut out the drinking or he’d tell the boy’s parents.

The boy agreed and the police officer drove away.

Thirty minutes later, the boy went into a drunken rage, attacked his friends and shut himself up in his house. When his friends tried to calm him down, the boy set fire to the house. The fire department did not arrive in time to save him.

Who, in the above instance, would be responsible? The boy, for setting fire to his own house? The parents, for leaving him alone with enough booze to float an armada? His friends, for encouraging him to drink? The police officer, for not completing legal action?

None of these people accept responsibility in a case like this, and more often than not, the people “blamed” will be the ones who had tried to help. In the case just described, the most likely “accused” would end up being the police officer, the police department, and the municipality of the city where the fire occurred. I have seen a case like this in which all these parties were sued by the dead boy’s parents, it being the parents’ allegation that the police were negligent in not arresting their son.

It is important that as fire investigators, we are not blinded by refusing to see how alcohol and drugs can be the contributory cause of a fire. Despite our reluctance to ask what might appear to be embarrassing, irrelevant, or unnecessary questions about a victim’s sobriety, it is vital that we pursue this avenue of inquiry.

When determining the cause of a fire, I would suggest that the fire investigator take particular note of the following:

If the victim has survived the fire, he may have been fully functioning prior to the fire—but also in a drug-induced blackout. If so, his memory of the events preceding the fire, including those that he himself might have precipitated, may be nil. Corroborate anything he may tell you with outside evidence or witnesses’ statements. Don’t hesitate to question neighbors about the life-style and habits of the fire victim.

- Notice such things at the fire scene as empty liquor bottles, pill bottles, and drug apparatus, which may quickly disappear.

- Look for inconsistencies, like fully clothed individuals found D.O.A. (dead on arrival) in their beds. People don’t normally go to sleep with their clothes on; they pass out. Other inconsistencies at a fire scene, such as inexplicable bruises on the body, toppled furniture, broken glass, disregarded smoke alarms, etc., may also be answered if you ask yourself: Would this make sense if the victim had been drunk?

- After an accidental fire stemming from drugs/alcohol, don’t disregard the possibility that the victim (or his relatives) may lie about what happened. Once the idea of a product liability lawsuit has been put in his head, he may eagerly describe how the back burner of the stove leaped into the air, did a triple back flip, and then attacked his highly flammable reindeer skin jacket at exactly the moment when he was making out a large contribution to the Catholic Charities.

- When and if legally possible, have tests for drug contents made on the victims of an accidental fire. If you enter into the case after the fact, check the medical and/or medical examiner records to see if such tests were performed.

The bottom line on cases involving “accidental” fires is to realize that, as fire investigators, the rules have been changed on us. It’s not enough just to know the specific point of fire origin and its cause. With attempts now being made to attribute and affix responsibility everywhere but where it belongs, we must be aware of the fact that a fire may be drug or alcohol contributory.