Changing Times Multiply Problems Of Managing Volunteer Departments

features

Compared with earlier years, it appears more difficult today to manage volunteer fire departments and to keep them improving as the need for community protection increases.

Indeed, the list of management problems grows more and more complicated and oppressive, ranging from poor budgets to more regulations to less time available for volunteer work. Not only is the list lengthy, but frequently it contains problems, such as inflationary price increases and gasoline shortages, which are beyond the control of department officers.

Typically, the various problems challenging volunteer officers seem to spread across all of the economic, technological, and social categories. Some are most difficult or even impossible to solve, so it is little wonder that many volunteer officers despair over their attempts to improve departments.

Some changes in our society, such as growing concern over arson, have been helpful to departments while other changes, such as increased costs, have been harmful. Some, such as technological advances, have brought about more helpful and improved fire fighting equipment, but have increased hazardous materials at the same time. Unfortunately, it is difficult to see clear gains for the fire service in any category.

Motivation of personnel

These more complicated problems, plus rapid change and increased pressures, mean that volunteer fire departments must also change with the times if they are to continue to serve their communities so well. But the management of an organization which must react to changing times is probably the most difficult kind of management. Thus, volunteer fire officers need to find new ways to motivate and lead personnel and new approaches to managing more efficient and effective departments.

Since the human factor in any organization is vital, personnel management is probably the most important job of any volunteer officer. Most officers agree that keeping the members working hard toward depart mental goals is more difficult than any other management task. For members to be productive, they must be reasonably satisfied. This means that members must be educated over a period of time to accept the mission of the department as their own. When they feel this way, belonging to a high-quality, task-oriented volunteer fire department provides self-motivation to personnel. Satisfaction stems naturally from being a part of an outstanding department.

There are at least four phases to personnel management: staffing the department with good people; training these people to perform the tasks; supervising, managing and leading members; and keeping personnel constantly improving their ability. These all require high motivation, but if members are motivated, then attainment will result in satisfaction and continued membership.

Three officer levels

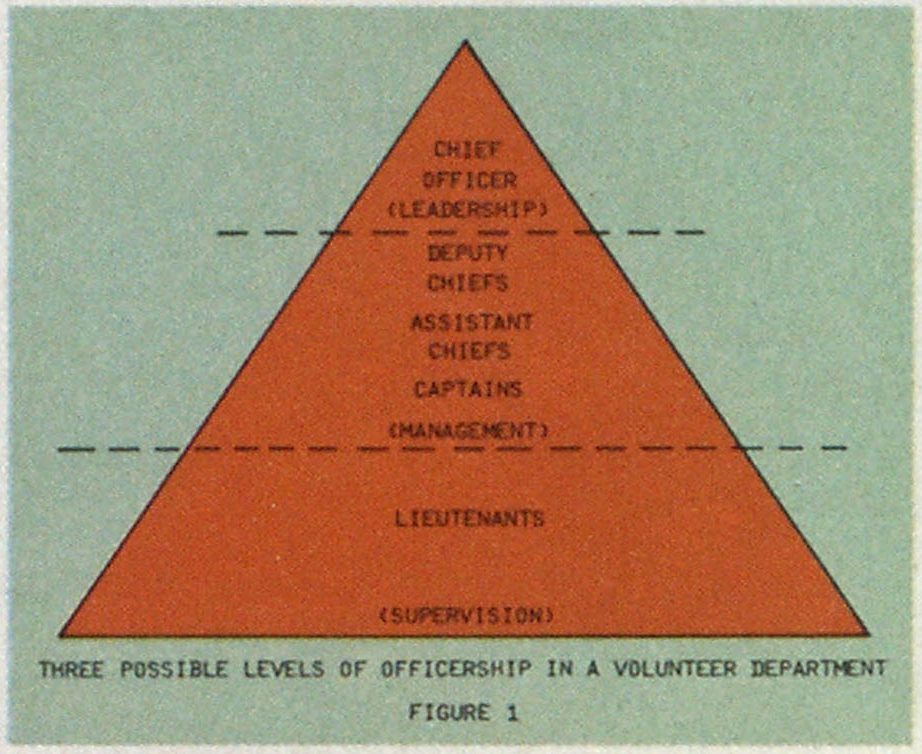

Successful volunteer fire department officers understand the three different levels of officership: supervision, management and leadership (see figure 1). While lieutenants are expected at times to provide leadership, and while chiefs may need to supervise occasionally, supervision, management and leadership are usually functions of rank in the departments. That is, as you rise in rank, you tend to provide less supervision and more leadership.

Company officers need to do whatever is necessary—including training—to be sure that the members working with them are doing their job satisfactorily. This is supervision. Captains, assistant chiefs, and similar ranks, are usually middle management and have responsibility for several units of people, such as two or more companies, or for larger functions, such as equipment and apparatus maintenance or training programs. They manage a group or a function.

Chief officers need constantly to predict the future of the community and to keep the department moving toward that future at full horsepower. This is perhaps the major act of leadership, and the primary role of the chief.

Officers who cannot distinguish between the instances when close supervision of personnel is necessary and those when general management of a set of activities is called for will always have problems in personnel management. Just as troublesome are those officers who know that they should give members some free rein (management at a distance), but who do not have the flexibility to be anything but an in-close supervisor of details.

Figure 2 illustrates that as an officer moves up the ranks, proportionately more time is spent in the administrative activities of supervision and management and less time in working with individual tasks in line operations. Sometimes officers don’t realize this and they attempt to perform—or closely supervise—all the work of the levels below them. Not only is this an impossibility, but it uses up the time higher ranking volunteer officers need to deal with the large picture, overall operations, and—most important—planning for the future.

No matter what rank, any officer can provide important leadership by getting behind junior officers and fire fighters and doing all that is necessary to boost them to higher levels. As strange as it may sound to some, effective officers work hard to get others qualified to move into officer ranks. This is a leadership role.

To be known as the best volunteer fire chief, one needs to have the best department, and that always means the best personnel. An old saying is that you can pull a piece of string across a table, but you can’t push it. Volunteer fire departments, composed of members with a variety of reasons for joining and with various levels of motivation, need to be pulled with good example rather than pushed by constant, tight supervision which does not recognize and respect the intelligence and talent of members.

Protection against reversal

When volunteer members are respected by their officers and their thinking is incorporated into long-range plans, the plans won’t be reversed when new officers are selected. One very inefficient aspect of many volunteer fire departments is that when a new chief is selected, the direction of the department changes drastically. Some members spend years thinking about how to become chief but not a minute about what to do as chief.

We must recognize that in 99 out of every 100 volunteer fire departments, the next chief is already a member. Effective chiefs have the department get the advantage of the talent and experience of junior officers and consequently the officers agree with the chief about the department’s goals and objectives. Then when a new chief is selected, the agreed upon plan is not changed needlessly and the department progresses in its ability to serve the community without having to return to the starting line.

The best organizational design for a volunteer fire department is the one which enables it to accomplish its goals most effectively and with the smallest amount of resources. Unfortunately, almost all departments are designed along the same historical lines, even though goals are expanding and important circumstances changing.

Examination of goals

The first step in considering how a volunteer department should be structured is to examine its goals and objectives. Most departments are organized only to fight fires, even though we realize today that suppression is just a part of the challenge. The broad range of prevention activities—from building plan sign-off, to code enforcement, to public education—cannot be ignored and, indeed, in many communities will emerge in the future as basic functions. Even though relatively few volunteer departments engage in those activities now, all should get organized to do more than simply fight fires once they start. A good example of how some departments have already reorganized to incorporate a new goal is the addition of emergency medical response units to fire fighting groups.

However, we cannot continue to expand our centuries-old organizational design to house such diverse operations as specialized training, emergency life support response, building inspection, code enforcement, building plan consultation, school programs, hazardous materials response, water rescue, mountain rescue, quick fire attack by air, home evacuation planning, natural disaster response, long-range community planning, and other needed services. The pressures for these services are already strong in some communities.

Additional pressures for change come from metro and regional planning, from township or countywide mutual aid operations, and from economic pressures to incorporate volunteers with paid departments or to cut costs in other ways. As departments continue to expand the services they provide, it seems reasonable to expect that they will need to redesign the way personnel are organized and the types and ranks of officers. They will also have to include more staff positions and specialty groups.

Volunteer departments can test these concepts simply by examining the organizational changes which have taken place in recent years in many large paid departments. The population of the community and the volunteer or paid status of fire department personnel could make little difference in t he need for prevention and specialized services, as well as traditional suppression activities.

Recruitment and training

Carefully planned recruiting and orientation programs are seldom used in volunteer departments, but they should be, since the strength of any department rests on its personnel. The proper process for acquiring new members consists of determining qualifications for membership, establishing a procedure for attracting people, screening out those who do not meet the qualifications, and orienting those who do so that there is clear understanding of the details of what is expected (figure 3).

Many departments never get to determining qualifications for membership, and some may make the error of having one set of “official” written qualifications and another unwritten set of qualifications used to keep out people whom some members may be prejudiced against. Not only is that method illegal, but it keeps out needed members who can do the job, decreases the strength of the department to serve the community, and harms the public image of the fire service. Those departments end up taking in only members who are not minority people but who really aren’t as well suited as fire fighters while leaving out those who can become productive, task-oriented members.

Legitimate criteria for membership may include a medical examination, a background check, a test of physical ability and aptitude, a residence or work location requirement, and an indication of willingness to meet training and department meeting requirements as well as to respond to fire calls and other department jobs. Those who meet the criteria should be admitted when openings exist.

Written requirements

Many volunteer departments set up conditional or probationary membership for a specified period, during which time the new member must meet certain requirements, including training, aptitude and attendance. These criteria should be written and publicized as well.

Immediately after being admitted, new members should be given a thorough orientation to the department, its structure, goals, regulations, expectancies and procedures. In some departments, spouses receive a brief orientation concerning what is expected of members so they will understand the time demanded of a volunteer.

While it is highly recommended that personnel attend basic, advanced, and specialized training programs offered by state and county agencies and by some colleges, nothing can replace departmental training, where fire fighters and officers train with their own equipment, in their own district, and under their own standard operating procedures. There is much more to a good training program than merely scheduling some drills. Long-range plans for training outline the topics to be covered for one or two-year periods and provide in-service refresher training, basic training for recruits, and training for new hazards, equipment and procedures.

Keep training records

All of this should be under the direction of a competent training officer, and adequate training and competency records should be kept for each member. Most effective volunteer departments mandate various types and amounts of training on an annual basis if personnel are to remain active members and specialized training if a member desires to become an officer.

“Training” is usually instruction and repetition in sets of skills, so that personnel can perform specific and known tasks readily. “Education” is usually the acquiring of knowledge so that unknown tasks may be carried out when new problems are encountered. Training and education need to be combined for fire service personnel so that routine jobs can be carried out efficiently and effectively and so that new situations—for which no training is available—can be handled. A rule of thumb is that jobs with greater responsibility require more education—the ability to meet new challenges. However, no department can exist without trained personnel who at least can accomplish routine work.

Since the purpose of training is to improve performance, training must be evaluated by checking the competencies of personnel, and each training item should be designed in terms of the desired outcome or competency. Since training is the practice of pre-planned actions which will be used to handle real emergencies, we calculate what training is needed by looking at history, sizing up the present and predicting the future. We consider the fire record, the current situation, and whatever future changes we are able to predict.

Basic problems

Designing training programs for volunteer departments requires much thought, since there are several fundamental problems:

- The problem of trying to reproduce future reality:

Since every reality situation is different and cannot be predicted exactly, training for reality cannot be based on exact replicas, especially in company level drills.

- The problem of seldom practicing the most important actions:

Individual skills such as attaching nozzles, tying knots, raising ladders, and advancing hose lines are concrete actions and can be reproduced on the training ground. Therefore, they constitute most of the training. However, they are often not the most important actions. The minimum “most important actions” seem to be combinations of these, carried out in different circumstances, which tend to cause operating errors (see figure 4).

The problem of infrequent reality situations:

Except in larger cities, real emergency situations seldom occur frequently enough to illustrate patterns or to provide practice.

- The problem of overcoming emotional behavior:

Reality situations generate emotions which detract from calm, effective and efficient actions.

- The problem of volunteer “nonmatching” personnel:

Volunteers must perform all kinds of tasks, sometimes including those for which a person may be untrained or ill-suited.

It is important to provide for officer training as well as for fire fighter training, and for training in prevention activities, such as inspection procedures, pre-fire planning and fire investigation. Much of the specialized and advanced training in both prevention and suppression activities needs to be obtained from sources outside a volunteer department. However, one of the greatest strengths of volunteer departments stems from the broad talents and versatility of its members. Often, a needed training skill is available within the department.

There can be no question over the importance of keeping open communication lines in a volunteer department. Because volunteers join for a variety of reasons other than salary, an inordinate amount of attention and time is paid to getting personal satisfaction through informal sub-groups and informal communication networks, such as gossip and rumors. If officers desire to reduce the communication flow of unofficial groups, they need to increase the flow through official lines of communication. In volunteer departments, communication will flow—one way or the other.

A second guideline for using communication as a tool to improve a volunteer department is to be sure that a feedback loop constantly operates (see figure 5). Obtaining continuing evaluation of how programs are moving is important for two reasons. First, feedback provides evaluation and ongoing evaluation enables chiefs and other officers to adjust programs so they can be more effective. This requires, of course, that officers remain open-minded and more interested in improving the department than in proving that they are always right.

Second, keeping a feedback loop operating illustrates to members that their thinking and evaluation of how things are going are important to the officers. It illustrates the kind of respect that motivates volunteer members to stay with the department and give backing to the officers. A constant flow of feedback results also in new ideas for improvement coming from personnel. This is highly desirable. Uptight officers who believe that no idea is good unless they have invented it themselves are a detriment to their departments. The task of a department is to improve its service to the community and not to enhance the egos of certain of its officers.

Making decisions

Along with open communication, the management function which holds the operation together and causes it to move ahead is decision-making. Just as communication provides the information, ideas, questions, directions, understandings, and evaluation for personnel, decisions pull everything together and cause action to occur. Without open communication and carefully considered decisions, all other management functions lead to very little.

Decisions made by officers in a volunteer fire department have an effect on two very important aspects of the organization: the ability of the department to do the job of protecting lives and property, and the motivation of members to stay with the department and perform at their best.

Because of the nature of volunteer membership, decisions sometimes must take both needs into consideration. For this reason, there is often a great deal of attention given in volunteer groups to the social and business activities. This social life is attractive to members and helps maintain interest in the department and a willingness to work hard and engage in the task during work periods.

Decision-making in volunteer departments which ignores the necessity for task accomplishment often results in poor prevention and suppression records and a dissatisfied community. Decision-making which ignores the social and morale questions may result in a heavy turnover of members and a low level of engagement in departmental work.

In training work and emergency situations, officer decisions must reflect the need to get the job done. In social and informal situations, decisions often should reflect the need to bring social satisfaction to many members. The best kind of decisions in volunteer departments are those which lead to a successful task and high morale of personnel at the same time.

Personnel management has been described as the most important and the most difficult aspect of total management. Whenever people are involved, the manager’s job undoubtedly becomes more complicated. Managing volunteers requires some special considerations, since motivation for salary is not involved. Much research indicates, however, that salary is not the best motivator of workers, and so respect, praise, and fairness become vastly important in most modern work situations.

Since all volunteer officers must work with personnel, all officers must function as personnel managers. In addition to recruiting, orienting, and training members, officers need to supervise, evaluate and help improve personnel. Good personnel managers know how to motivate their people, how to reward good work and improve unsatisfactory work, and how to deal fairly with special personnel problems.

Basic techniques

Because few volunteer officers are experienced personnel managers, attention needs to be given to some basic techniques: clear and frequent communication, including different types of communication for people who learn best in different ways; clear lines of authority and responsibility with consistent enforcement of policy and regulations; standard operating procedures for administrative matters to reduce conflict and misunderstandings; encouragement to participate and to keep learning; treatment of problems and complaints in a fair and nonpersonal way; recognition that each member is different and respect for those differences.

Many kinds of people join volunteer departments, and not all join because they have a strong interest in providing good fire protection for the community. Their reasons—which are usually well intentioned—range from business reasons to social reasons to the need to achieve a position of authority in some organization.

Almost all these people have the potential for becoming good, task-oriented, productive members, but they require carefully thought out personnel management to achieve their potential. They require fair treatment, encouragement, and respect for their talents and potential ability. Not every member will become a good member, but most members certainly can with proper leadership. Almost anyone can manage highly motivated personnel who want to get the job done. The real challenge comes from those members who have the potential, but who need the expert skill of the officer.

Adopting to challenges

Most officers desire to improve their departments, and sound management practices can do much to help. In order to change a volunteer department, all personnel need to be involved, not just the officers. Members are much more likely to cooperate if they have been involved in helping to plan the changes and if their suggestions are respected and used by the officers as plans for improvement are prepared. Not every member will be satisfied and happy with every change, naturally, but in volunteer organizations, careful consideration must be given to the need members have for getting satisfaction from all aspects of department life.

Good management practices, including planning, communicating, supervising, and evaluating, will keep the department operating smoothly. Good leadership will keep it moving ahead to meet the challenges of the future.

Although communities across the nation are changing, and although the need for new kinds of services delivered in cost-effective ways is quite strong, volunteer departments will be able to change, to improve, and to provide what citizens need under the direction of dedicated and thoughtful officers.

The Author: Dr. Granito joined a volunteer department at 18 and has been deeply involved with the fire service ever since. Titles that he has acquired along the way included supervisor of fire training for the State of New York and director of the International Fire Administration Institute. He has also been an educational consultant for the International Association of Fire Chiefs and the National Fire Protection Association.