Coal Bed Fire Threatens Pa. Town After Burning Underground 19 Years

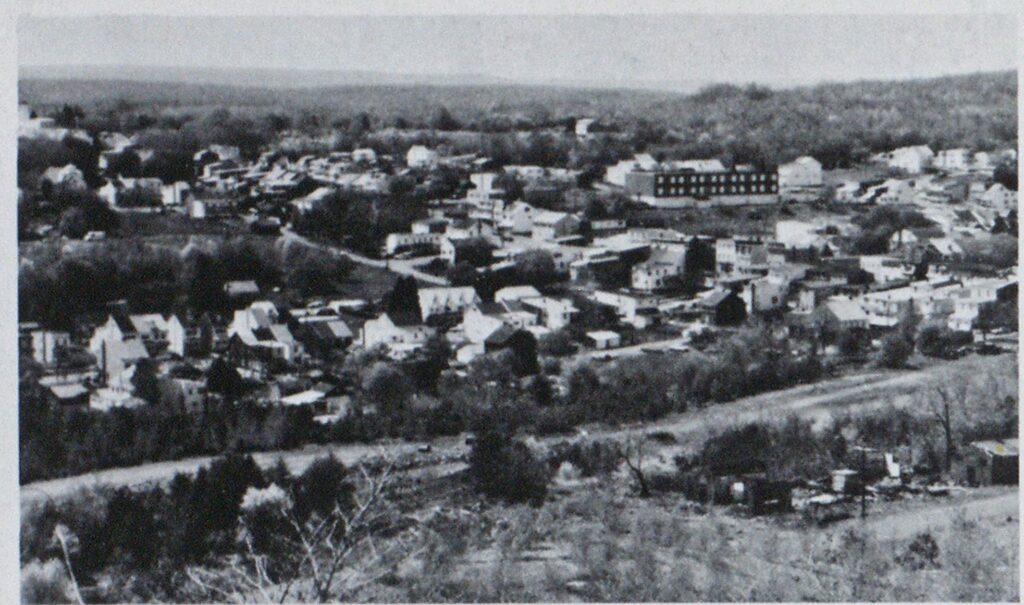

For the last 19 years a fire has been burning out of control in Centralia, Pa. More accurately, the fire is under Centralia. The town was built over a vast bed of coal covering 94 square miles, and 140 acres of that underground fuel are burning. No one knows how or when the fire will be extinguished.

Centralia has been a mining town almost continually since 1842, although it dwindled after World War II. The coal under the town is some of the hardest anthracite ever mined.

Fire department not called

The long-lived fire was discovered in May 1962 in a waste disposal area operated by the borough southeast of the town, near the entrance to the Buck Mountain coal bed. But the fire department was not called.

Borough workmen tried to put out the fire with water and inert powdered clay, but it spread to the outcrop of the coal bed and started burning along the strike.

The fire department still was not called to the location.

The State of Pennsylvania hired a private contractor to stop the fire.

“We almost had it out,” he said. “It was only 200 square feet then, but we ran out of the money our contract called for. We needed just $10,000 to $20,000 more to do the job.”

Months passed while state officials put the extra work out for rebidding. The fire continued to spread.

The federal government entered the picture in July 1962 and decided to dig a trench to stop the spread of the fire. But by the time a contract was awarded, the fire had spread past the point where the trench was planned, according to a Bureau of Mines report.

It was then decided to begin a process called flushing, which consists of holes being drilled in the earth above the fire and material such as sand or fly ash being dumped into the mine. This effort failed, as did several other attempts that followed.

More money was found for another control effort after the passage of the Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965. Cooperating in what was called Project 53 were the United States Department of the Interior (Bureau of Mines, later joined by the Office of Surface Mining) and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Department of Environmental Resources and Columbia County).

No answer

Various officials studied the problem, one with a simple question: How to best put out the fire? No simple answer was found. It may go down as the most expensive fire in the history of the United States. Thus far, over $3 million has been expended by Project 53. Before it’s over, an additional $85 million may be required to do the job.

A report prepared by the Bureau of Mines and the Office of Surface Mining gives the details of the fire, an assessment of the hazards involved and technical problems involved in controlling the fire, and makes recommendations as to what method of fire extinguishment and control should or should not be taken. The report was published on Aug. 15, 1980.

“The continued spread of the fire,” the report declares, “presents a hazard to a portion of Centralia Borough. Combustion gases from the fire have penetrated some homes; and the presence of CO and the long-term effects of low-level CO2 exposure and O2 deficiency are the immediate public health and safety problems caused by the fire: Natural geological barriers will protect part of Centralia and eventually limit the progress of the fire in all directions. However, if the fire is allowed to burn to these limits, an area of 1500 acres and approximately 320 structures in Centralia will potentially be affected.

National attention now

Centralia came to national and international attention when John Coddington, who operated a gasoline station in the town, was overcome by fumes in his home. It was not the first time he had been affected. Two years ago the temperature in his basement reached 180 degrees. There was alarm that the underground gasoline tanks might explode and endanger the entire town, which consists of mostly wood-frame buildings. Coddington pumped out 8000 gallons of gasoline from his tanks and the station closed.

Then came Valentine Day of this year when the ground in Carrie Wolfgang’s backyard opened up and almost swallowed 12-year-old Todd Domboski. Todd held to a tree root until his cousin Eric Wolfgang found him and pulled him out.

‘‘If it wasn’t for the red hat,” Eric said, “I never would have seen him.”

Temperature readings taken later at the hole showed 300° F.

Meters measure CO, C02

Ecolyzer meters have been placed in 30 homes to monitor oxygen deficiencies or the presence of carbon monoxide (CO). The oxygen meters sound an alarm when the oxygen level falls below 19.5 percent (normal 21 percent). The CO level is considered dangerous when it registers 7 ppm. When I visited Centralia, the CO level at 8 a.m. in Fire Chief William Klementovich’s home was 30 ppm. Klamentovich hopes that he and his family will soon be moved to temporary quarters in a mobile home that the state is setting up in another part of town.

Thus far, eight homes have been condemned and destroyed because of instability of their foundations and the presence of fumes. The Office of Surface Mining proposes limiting its disaster relief to $1 million, to be used for the purchase of perhaps 30 homes under which the fire burns strongest. Divided 30 ways, after subtracting administrative expenses, the money would yield each Centralia home owner in the impact only about $25,000.

Methods of control

Meanwhile, officials ponder how to proceed with extinguishment attempts. The August 1980 report of the Bureau of Mines outlines methods used to control mine fires:

- Excavation is probably the most successful method used to date. The problems encountered are finding a site for the excavated material and a water supply to extinguish the fire as exposed. The presence of surface improvements (buildings) complicates the picture.

- Inundation is filling the mine with water. It can be used only where the geology and physical conditions are favorable. This is not favorable in Centralia because the seam is at a 60° slant. When water is poured in, it simply slides to the draining shaft at the bottom of the mine and comes out on the other side of the town.

- Flushing consists of drilling holes above the fire and dumping inert material into the mine. During a seven-year stretch, $2.8 million was spent drilling 1700 bore holes and pumping over 1 million tons of fly ash and 100,000 tons of sand into the mine. This method failed.

- The fire barrier method consists of a noncombustible dam placed between the fire and the contiguous coal. This barrier can be a trench barrier, tunnel barrier or a plug barrier. Present evidence suggests that none of these methods would work at Centralia.

- The surface-sealing method is intended to exclude air from the fire. It is generally applicable to fires in virgin outcrops.

All methods of extinguishing the Centralia fire are complicated by the extensive previous mining done in the area. Further, there is the presence of hydrogen in the area, which will accumulate in openings above an active fire area. The repeated accumulation, exploding or burning of hydrogen-air mixtures can communicate fires long distances along barrier pillars.

‘‘It is apparent that fires can exist for as long as 15 to 25 years with no surface indications,” the government report states, “and then become ragingly active in a very short time after the ground is disturbed by pillar mining in the seam below.”

Looking at excavation

The chief advantage of excavating is that it has the highest probability of successfully extinguishing the fire, and that the project surface area would be usable for future development.

The disadvantages of the total excavation plan are: an extremely high total project cost ($84 million), the destruction of 109 structures, the relocation of state highway Route 61, and the relocation of a natural gas line and surface utility lines. A six-year plan would require equipment capable of excavating 22,000 cubic yards per day and an annual budget of $14 million. All of the above would have a tremendous social impact on Centralia.

A met hod of continuous underground spraying was considered as a method of containing the fire. The basic premise is that if a sufficiently large area were kept cold and wet, the fire could be isolated in a particular area.

The proposed method calls for continuously spraying water into the three steeply pitched, abandoned coalbeds adjacent to the affected area. The water spray system would include a series of 4-inch steel pipes with highpressure spray nozzles, extending from the surface to slightly below each bed. Specifications would call for spray units on 20-foot centers. A deep well pump would be installed to draw the water from a pool approximately 450 feet below the surface.

The disadvantage of this proposal is that the system would have to be operated seven days a week for 20 more years to achieve total control of the fire. Also, this method has never been tried, even on a small scale.

Even if the fire were contained by this method, it is possible for cold combustion gases to migrate through the water curtain and cause fume problems or even reignition of the fire on the cold side of the water curtain.

Fire 1, town 0

A proposal has been made for the federal government to buy up the town and relocate it. U. S. Representative James Nelligan recommended a referendum on the project. It was opposed by Mayor John Wondoloski, who cautioned that there was no guarantee that funds to relocate the town would be forthcoming.

In a regular election held last May 19, with 79 percent of the registered voters casting ballots, the final result was a 2 to 1 vote in favor of moving.

Where will the people go when they move? Who will pay their expenses? What will happen to the homes they leave?

The State of Pennsylvania has offered only short-term help for those families in immediate danger by moving them to mobile homes. .

“The fire is out of control, burning and moving fast,” says the Office of Surface Mining, “but the OSM can offer no help until it completes a new study.”

U. S. Senator John Heinz has promised to seek help from the Department of the Interior.

The people are afraid to move and afraid to stay.

A town appears doomed by a fire that perhaps could have been handled easily in the beginning—if the fire department had been called then.