“Mayday, Mayday, Mayday,” rang loud over the portable radios from the Engine 101 officer. There was an immediate silence from all personnel on the fireground; the only sound was the loud hum of the engines of parked apparatus. Brown smoke pushed from the windows, doors, and eaves of the 8,400-square-foot home. On the scene for one minute and 45 seconds, the third-due engine and second-due truck were assigned to rapid intervention (photos 1-2).

(1) An aerial view of the fire building. [Photos by Howard County (MD) Department of Fire & Rescue Services (HCDFRS).]

(2) Engine 61’s crew attempted to enter side A to cool the fire from above but couldn’t because of conditions. Soon after, they redeployed to side C to make an additional RIT, if needed.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Uncommitted Tactical Reserve Assignment: The RIT Assist Team

Rapid Intervention: Focus on the R’s

The Scenario

On July 23, 2018, Howard County (MD) Department of Fire & Rescue Services (HCDFRS) suffered its first career line-of-duty death (LODD). The fire was a result of a lightning strike that occurred at approximately 0120 hours. The strike followed a corrugated stainless-steel tubing gas line into the basement crawl space of the large residential home.

The 911 call came into the communications center at 0153 hours for the report of visible smoke inside the home. HCDFRS dispatched a local box: two engines, one ladder, one paramedic ambulance, and a battalion chief. The first-due engine arrived at 0200 hours and reported a single-family home with smoke showing and requested the full box alarm, which added an additional two engines, two ladders, one paramedic ambulance, one safety officer, one medical duty officer, and an additional battalion chief. The initial crews on scene had to operate despite water supply issues, limited staffing, a mansion with an odd layout and grade changes, and an unknown fire location and extension (photo 3).

(3) This shows side C after the RIT had exited and our fallen brother had been taken to an awaiting ambulance.

Mayday and RIT Response

Over the next 15 minutes, crews deployed into and exited the home multiple times from different locations to try to locate the seat of the fire. Fire eventually broke through the floor, was showing on the main level, and was observed by crews making entry into the basement. The second engine on scene, Engine 101, pulled a third attack line from the first engine, Engine 51, and redeployed into the main level on the upper grade of side C. Within minutes, the nozzle firefighter on Engine 101 fell through a hole in the floor and into the basement crawl space; the Engine 101 officer sounded the Mayday at 0220 hours (photo 4).

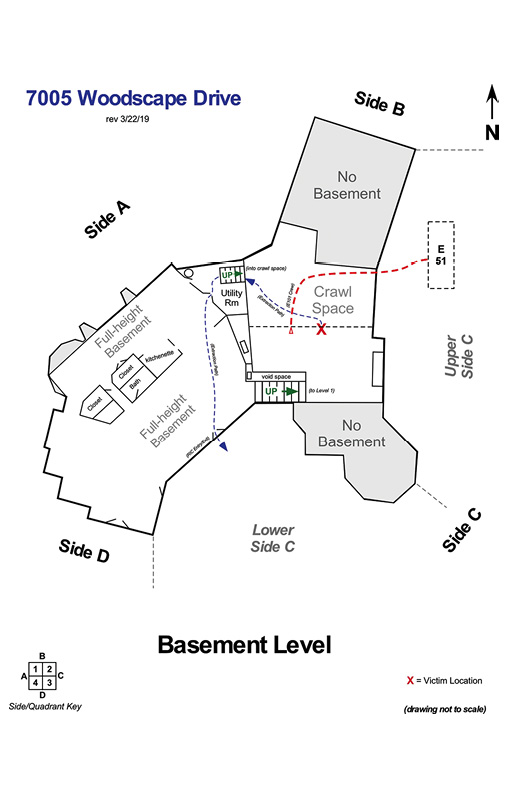

(4) The down nozzle firefighter had entered through the upper side C laundry room entry on the first floor and fell through the floor into the basement crawl space. The RIT entered through the lower side C basement entrance and up the stairs to the crawl space. There, they found the down firefighter and removed him by the same route.

I was the officer (Engine 71A) on the third-due engine and ran around to side C along the D wall to investigate the best line redeployment; the truck crew, Truck 7, covered side B so crews could complete the 360° survey together. Engine 71’s crew redeployed a charged 300-foot, 1¾-inch line around the D wall and was formally reassigned to team up with Truck 7 as the rapid intervention team (RIT) at 0222 hours. Engine 71 and Truck 7 positioned at the lower side C basement door. It was during the next minute or two that crews tried to ascertain where Engine 101’s line was deployed, what their probable location would be, and who was still not accounted for. At 0225 hours, we were advised that the Engine 101 nozzle firefighter had fallen through the floor while on his hoseline and went “one floor below grade level, through a hole in the floor.”

There were still reports of potential missing firefighters who were eventually accounted for. The RIT deployed into the structure through the side C basement door. We initially encountered little heat but near-zero-visibility smoke conditions. After searching that area of the basement with negative results, crews found an interior half set of stairs near the side A wall in the basement. We went up the stairs to find high heat, zero visibility, and fire showing through different spaces and materials on either side of us (photo 5, Figure 1).

(5) The stairs leading to the basement crawl space where the down firefighter was found.

Figure 1. The Basement and Crawl Space

We had entered a five-foot-high, 1,000-square-foot unfinished crawl space that sat under the main level of the home but was offset and above the finished portion of the basement. The walls were concrete block, the flooring was unfinished plywood, and there was unprotected dimensional lumber above. The space was packed with catering equipment, folding tables, and chairs for dozens of people, holiday decorations, and various storage. Throughout the next few minutes, heat and fire levels changed rapidly and continued to drive the RIT to their knees. The nozzle firefighter, Engine 71B, applied the first water on the fire from any unit on scene; the fire had been burning unchecked for one hour and 17 minutes from ignition.

After crawling about 10 to 15 feet into the crawl space, I could hear an activated personal alert safety system (PASS) device in front of me and verbalized the same to the Truck 7 officer (Truck 7A). Using a thermal imaging camera (TIC), I could not readily see a down firefighter, but I did notice various levels of fire and heat all around us, much of it blocked by the various storage. It was also during this time, as crews were trying to advance forward, that multiple entanglement emergencies occurred. Truck 7A, Engine 71B, and I (Engine 71A) became entangled in various wires that had fallen from the ceiling. I used my cable cutters and cut away the wires in front of me that were pulling across my chest. I then freed the Truck 7 officer, who had wires pulling across his back, encircling his torso, and inhibiting him from moving about. Looking over to Engine 71B, I noticed he was crouched and bent over his handline. I asked Engine 71B to continue to knock down the fire that had been growing around us. Calmly, Engine 71B advised that he and the bail of his nozzle were entangled and that he would not be able to put out any more fire until he was freed. As the fire grew around us, I had just enough light to see the wiring. Fortunately, I was able to free him, and he continued his suppression efforts and kept the fire in check. Truck 7C (the outside ventilation position) assisted in freeing more wires that had dropped in our exit path, separating RIT members from each other. I then told Truck 7C to tell the remainder of the RIT to “single stack” on the stairs in case the room flashed, giving the personnel at the top of the stairs room to bail back down, if necessary.

Down Member Found

I sounded the floor with my halligan bar; it seemed to be a sturdy floor in front of us. Once the wires were cleared, Engine 71C (backup position) advanced and found the down firefighter in front of us about 10 feet ahead of where the entanglement occurred. Engine 71C had his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) transfill line out and ready if it was needed, ensured that the down firefighter’s mask was on securely, and verified that he had air in his cylinder. As Engine 71C began to lift and remove the down firefighter from the area, I advanced up to assist and decided to drop my tools.

Once Engine 71C removed the down firefighter from the debris, we, in a coordinated and timed effort, horizontally dragged him to the top of the stairs back through the narrow pathway in the crawl space, approximately 25 to 30 feet back to the set of steps where we entered. Once Engine 71C and I made it to the top of the steps with the down member, we passed him onto the awaiting members of Truck 7. These members made the concerted effort to remove the down firefighter down the interior stairs, through the basement, and on to other fire department personnel and awaiting emergency medical services (EMS) personnel. All RIT members exited together with the down firefighter 15 minutes and 5 seconds after entering the basement.

Though it is not the outcome anyone wants, the RIT was successful in that they extracted a down firefighter in an 8,400-square-foot home with an odd layout and design, battled near-flashover conditions, and managed an entanglement—with no other injuries.

Key Takeaways

Here are three key takeaways, among many, on why the RIT from Engine 71 and Truck 7 were successful that fateful evening.

Unit Cohesion

The members of Station 7 had been assigned and have worked with each other for anywhere from one year to 10 years. The least senior member has more than 10 years of firefighting experience; the most senior member has more than 30 years; combined, there was more than 130 years of firefighting experience. Additionally, the entire crew was assigned to Station 7. In the all-too-common era of details to cover leave spots, frequent transfers, Kelly days, and sick calls, each member assigned to the RIT was a member from Station 7. It is a recurrent thread in National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) reports to see “acting officers,” “detailed personnel,” and “understaffed units” as contributing factors to an LODD. However, the members had each other to rely on.

We have spent years training and running incidents together. As soon as the parking brake is set, all members have been trained to the point where they work on their assignment without anyone saying a word. No orders need to be barked; expectations were set long before, and everyone intimately knows their roles and responsibilities. Each suspected false alarm is treated as it is the real thing; we wear all our gear, pull lines, and throw ladders.

But it runs deeper than that. Our wives spend time together, our children play together, and we spend time away from the firehouse together and break bread. So, we have a deep respect and trust for each other. That trust, combined with an intimate knowledge of how each other performs on the fireground, is an irreplaceable trait that bonds the crew, which is not seen in shifts that do not have that level of comradery. Interpersonal stability is an intangible element in healthy team performance, and Station 7 has developed this quality over many years together.

Mission-Oriented Training

The engine bay is darkened, except for the little bit of light peeking through the sides of the contractor trash bags hung over the engine bay door windows. Sections of 4-foot × 8-foot plywood have been attached to both sides of the forcible entry prop doors, simulating a narrow hallway. All crew members are wearing their personal protective equipment (PPE), their SCBAs are on, and they are ready to breathe air. Prior to the start of the evolution, they are told, “Visualize that it is 3 a.m., you’re on side C of a working basement fire in a single-family home, standing in front of a metal basement door at the bottom of a walk-up staircase. The engine crew is behind you with a charged hoseline waiting for the door to be forced, and there is a report of people trapped in the upper bedrooms.”

Before you can begin the evolution, you must clip into your mask-mounted regulator and do 15 push-ups in your gear. Then the evolution begins. You are not able to see much, but what you do hear is the clear communication between a two-person forcible entry team, the “hit, hit, drive, stop,” as the metal on metal rings out. The wood breaks, the door opens, and the team controls the door. The evolution begins again; each firefighter cycles through with a partner and then goes through again alone. By the end of the last evolution, every single person has succeeded, and everyone is sweaty and grinning.

If I were to begin with this evolution, the success rate would plummet. Adrenaline would be high, emotions would be tense, and no information would be heard because of the anxiety. Thirty-year veterans have been seen with darting eyes and nervous glares. However, no matter what the specific training is, we begin every single training goal with the fundamentals. The intention is to build confidence and to ensure the entire team is brought up together with the same information sharing. We work on the “why” and “how,” talk about the training expectations and goals, discuss the equipment and its function, and work on the necessary and desired movement patterns to build the motor memory.

As time passes, we throw on our full PPE and SCBA and add more curveballs to the mix. When efficiency becomes the new norm, and only when everyone is ready, we will proceed from these practical training scenarios and add a twist that could happen on the fireground: “Hey, guys, I don’t know who snuck the crib into the firehouse, but we missed the baby in the crib when we did that search; let’s do it again.” Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast, but fast cannot be hasty, and fast must be accurate.

Stress Inoculation

The back end of the training stimulus is stress inoculation. Laurence Gonzales, author of Deep Survival, says this of training: “All elite performers train hard, and when you follow in their path, you’d better train hard, too, or be exceptionally alert … we face the same challenges experts face. Nature doesn’t adjust to our level of skill.” Fire also does not discriminate.

Once the fundamentals are second nature and common troubles are mitigated, we must learn how to deal with failure. Throughout all the sets and repetitions we perform, executed with diligence and purpose, we must ratchet up the level of stress in the training so it may become realistic. The goal is to get the adrenaline moving, but it also needs to drive home the notion that things could always become worse and that we need to be ready to handle that risk. When adrenaline spikes, we need to use it to our advantage. At a certain point at a working incident, our heart and breathing rates increase, which can lead to tunnel vision, a loss of fine motor skills, reduced cognitive decision-making ability, and diminished hearing; this is known as “Condition Black.” Once you hit Condition Black, your compromised ability to function is not only deleterious to you, but you have now become a liability for the crews working with you. This is partly the reason many firefighter LODDs or near-misses have resulted in a cardiac event. The adrenaline dump and cardiac loading from an emergency incident are too much for the person to bear. This is why difficult training, when crews are explicitly ready, is absolutely necessary. It builds confidence, ensures readiness, and prepares the crews for the unknown.

Retired Colonel David Grossman, author of On Combat, The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace, says this of fear and stress inoculation: “A simple set of skills, combined with an emphasis on actions requiring complex and gross motor operations (as opposed to fine motor control), all extensively rehearsed, allows for extraordinary performance levels under stress.” In laymen’s terms, the research shows that when someone is properly trained, over time, the metabolic and adrenal stress that one encounters can help focus the individual who is trained, compared to the one who has not prepared for such an event. Additionally, all of our skills are perishable; they must be maintained throughout our careers. The final outcome should be that if you are involved in a real incident, it should feel easier than the training you have completed in the past.

Human Performance and the Occupational Athlete

Roughly 50 percent of firefighter LODDs are cardiac related, an all-too-familiar statistic. The unfortunate reality is that much of that statistic is also preventable. We must treat our professionals like the occupational athletes we are. If our fireground training is supposed to replicate that, so must our physical fitness training. If you are someone who can run a five-minute-mile pace for 26 miles but cannot lift your body weight, there’s a hole in your fitness. If you can deadlift 600 pounds but get winded going up steps, there’s a hole in your fitness. We need these two worlds to mesh. We need firefighters who are strong enough to carry themselves and potentially their unconscious partner in full gear out of a burning building and have the cardiac capacity to be able to handle that workload. This is where high-intensity interval training comes into play.

In the incident described above, while dealing with an entanglement, a superheated environment, and having to drag an unconscious firefighter out of a mansion, crews worked within 90 to 100 percent of their maximal perceived effort and surely at or near their maximal heart rates. It was not until crews began to exit the crawl space that low-air alarms began to sound. Once we made it out of the structure, we dressed down and were completely exhausted; but we still had 1,000 pounds per square inch left in our cylinders. For me, the hormonal dump and physical exhaustion I experienced that night left me less than 100 percent for nearly two weeks after.

During the preceding year, our shift had been working out using high-intensity interval training (HIIT) methods. It is a simple mix of repetitions, designed to work for a predetermined amount of time (much like working with the air in your SCBA) or a predetermined amount of repetitions (a set number of tasks needing completion before being recycled). The goal is to use common movements found in the fire service, vary them as much as possible, and perform them quickly. The difference between HIIT and conventional strength or cardio workouts is the primary metabolic driver is anaerobic, the glycogen and phosphagen systems in the body, compared to oxygen powering the workout. It is not necessarily meant for long-duration workouts, though anaerobic will make you more proficient in that area as well.

Think of the work capacity of a marathon runner compared to a gymnast. Gymnasts weight train, perform cardio, and use bodyweight movements and are pound for pound some of the most skilled athletes in the world and multiversatile in other sports. Marathon runners typically perform in a single, monostructural domain. Simple, yet challenging, functional movements should mimic the work we are required to perform on the fireground.

The goal is not only to increase your work capacity but also to increase your recovery time and your mental toughness. Knowing what your safe outer physical limits are should be a confidence builder when met with physically hard tasks. The first time your adrenaline is pumping, your heart rate is high, and you are in an uncomfortable environment should not be on an emergency incident. Common excuses like “I have more experience,” “I work more efficiently,” and “my adrenaline will get me through” are no longer valid; you are a liability. You must know exactly what you are physically capable of doing, and by working out in modes where you are tasked to complete as much work as possible within the shortest time frame, you’ll soon find out.

Additionally, make sure you are honest with yourself. As a fellow trainer once said, “Scaling isn’t sailing.” Make sure you are performing your workout safely and with proper form to reduce the risk of injury. Ideally, do it alongside someone experienced or certified.

I commend the members who worked on the RIT on that fateful night. They were called to act and, when faced with severe hardship, they overcame every obstacle thrown at them. But this is not something that happened in an instant. This was done in an environment that was cultivated over a period of years. Mission-oriented training, progressive stress inoculation, mental and physical human performance, and unit cohesion were major players in the team’s success, among many others.

I challenge the fire service to look inward and ask if we are doing everything that we can to uphold the expectations our communities have placed on us. It is our promise, and we should deliver.

References

Gonzales, Laurence (2004) Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why : True Stories of Miraculous Endurance and Sudden Death. W.W. Norton & Co.

Grossman, David; Christensen, Loren W. (2007) On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace. PPCT Research Publications.

JOSH BURCHICK is a lieutenant with Howard County (MD) Department of Fire & Rescue Services (HCDFRS) and has more than 15 years of firefighting experience. He is HCDFRS’s lead trainer for the IAFF’s Fire Ground Survival Program, an ACE-certified peer fitness trainer, and a nationally accredited CrossFit trainer. Burchick has a bachelor’s degree in public safety leadership from Johns Hopkins University.