Communications aren’t usually the first thing that comes to mind when discussing fireground operations, training, and the overall work we do to ensure that we are prepared to do whatever it takes to serve the citizens we are sworn to protect. Unfortunately, fireground communications are almost always brought up after the fact. We generally focus on communications during after-action reports (AARs), postincident analysis (PIA), and line-of-duty death (LODD) reports. That being the case, the fire service should adjust its focus and bring the topic of communications to the forefront, just as we do for fire dynamics, fire streams, forcible entry, vent-enter-search, and myriad other fireground-related topics. One of the ways we can accomplish this is through good old-fashioned leadership.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Conditions That Warrant Urgent Communications to Command

Throw Back to Basics: Fireground Communications

Fireground Communications: From Size-Up to Mayday

Communicating Expectations

There’s no shortage in the amount of leadership information available today. Books, magazines, and podcasts are the most common areas where the importance of setting expectations is discussed. As leaders (not just brass), we must not only set the example but set and communicate expectations to our crews as well. Some of these expectations regarding fireground communications follow.

(1) It’s important to incorporate a communications component when training, especially during Mayday drills. Here, the incident command engineer communicates with a “down firefighter” on the Mayday channel while the battalion chief communicates with fire crews working on the fireground channel. (Photos courtesy of author.)

Know how to operate your radio. Although this may seem like an obvious and foregone conclusion, check again. It’s common to find someone who isn’t 100 percent certain of how to operate his radio; this includes knowing what each button does and on which incident type the preassigned channels are based. It also means quickly accessing radio channels for the departments for which we may provide mutual or automatic aid. If indicated by your department’s standard operating procedures, what happens when you push the “Emergency Activation” button on your radio? Consider the following:

- Carry your radio properly on every single incident—this means that for any incident on which you are required to wear bunker gear, carry the radio in a harness under your coat. Too many times, I’ve seen firefighters on medical calls without their radios. Why? The simple answer is that their officer didn’t set it as an expectation. So, what if it’s the officer without the radio? This means the battalion chief (BC) didn’t set that expectation. Regardless of incident type, have your radio with you at all times.

- Know when and—more importantly—when not to talk on the radio. Just because you have a radio doesn’t mean you have to talk on it.

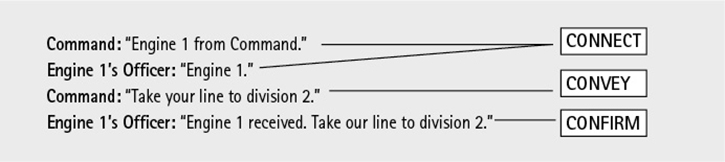

- Use your department’s adopted communications model. Our department has adopted a “3 Cs” communications model (Connect, Convey, Confirm). It never ceases to amaze me that we continue to hear officers (and even chief officers) using old-school, outdated terminology such as “Go ahead” to answer when called on the radio. The problem with answering “Go ahead” when we are called on the radio is that we aren’t making that “connection.” Figure 1 shows an example of the 3 Cs communications model that highlights the importance of making the connection. In Figure 1, if Engine 1’s officer had answered with “Go ahead,” Command would know he made a “connection” with somebody, but did he actually connect with Engine 1? When he answers with “Engine 1,” the connection is confirmed.

- Give brief size-ups. This includes getting rid of lengthy descriptions and replacing them with “plain speech.” For example, instead of saying, “Engine 1’s on scene, we’ve got a one-story, single-family residential structure,” why not say, “Engine 1’s on scene, we’ve got a one-story house”? In other words, if you are giving a size-up for a house, simply call it what it is—a house! Keep it simple.

- Train! I could write an entire article on this topic alone (see my article “Improving Fireground Communications Through Training,” Fire Engineering, May 2019, https://emberly.fireengineering.com/2019/05/01/223047/improving-fireground-communications-through-training). Be creative. Think of ways to incorporate communications into your training. For example, before you pull lines or run through a scenario, do a size-up over the radio (use a designated training channel or a talk-around channel, if you have one). Also, when training, make it as realistic as possible. Part of that includes wearing proper personal protective equipment. Operating the radio while wearing fire gloves can be difficult. However, it will be a lot easier with practice.

Figure 1. The 3 Cs Model of Communications

The Command Post Location

A question that seems to come up a lot is, “Where should we locate the command post?” First, the fact that this is even being discussed should be celebrated; it means more people (especially officers and chief officers) are becoming engaged and thinking about what they can do to improve in their role as the incident commander (IC).

When deciding where to locate the command post, there are many variables to consider. What is the type and size of the structure? Is it easily accessible? Will I have a good vantage point? What are current fire conditions? The answers to each of these questions should help you decide. Let’s look at the options.

Commanding from the Yard

To better explain what is meant by this statement, let’s look at two scenarios. In both, the building type, fire location, department staffing, and all other factors are identical.

Scenario #1. The BC is in the front yard of a one-story house with a reported bedroom fire. He’s standing in one spot, out of the way, by the sidewalk (about 20 to 25 feet from the front door), and his head is tilted toward his radio’s extended mic. He’s studying the structure, observing the smoke conditions that he sees coming from the eaves on the Bravo side, and making a few face-to-face assignments. He’s calm and in control. His aide (command technician) is standing next to him, head also tilted, clipboard in hand, taking notes and tracking the location and assignments of working crews (accountability). This command team realizes that the closer they are to the incident, the more likely they will be distracted, thereby missing important radio communications. Keeping this in mind, they keep their distance and don’t miss a single radio transmission. The decision to run command from the front yard in this situation proves beneficial.

(2, 3) Face-to-face communication is a great way to cut down on radio traffic. However, be careful not to become distracted by this. One of Command’s most important jobs is to answer the radio the first time, every time.

Scenario #2. The BC is in the front yard of a one-story house with a reported bedroom fire. He’s pacing quickly back and forth across the yard, looking through the front door, talking to crews as they go inside, and getting updates from those coming out. It’s a busy scene, and he’s yelling over the noise from the gas-powered fan that’s only five feet away. He hurries over to the Alpha-Bravo corner and then back across to the Alpha-Delta corner while his aide tries his best to keep up. In the meantime, they missed a couple of radio transmissions from crews trying to reach Command. After a couple of tries, when Command still doesn’t answer, they give up trying to reach him and continue to work. With all of the pacing back and forth, the aide hasn’t been able to keep track of all of the working crews. If the fire goes out and nobody gets hurt, they will consider that they have done a good job and will most likely do the exact same thing on the next fire. In this case, commanding from the yard was chaotic and unorganized. Some of the crews are frustrated because they weren’t able to reach Command on the radio. Ultimately, they lost their confidence in Command.

Scenario Comparison

Imagine how things would have gone for each scenario if a Mayday had occurred. Either way, it’s going to be stressful, but only one of the command teams was prepared for it. The key takeaways in establishing command from the front yard include the following:

- The closer the command team is to the work being done, the more likely it is that they will become distracted and unable to effectively do their job.

- Missing radio transmissions is unacceptable. As the late Chief Alan Brunacini stated, Command must be “open for business.” Crews will generally try to reach Command twice. If they are unable, they will stop trying and continue working.

- The successful command team in Scenario #1 was disciplined, had a plan, and was aware of the potential pitfalls that could occur when taking command from the front yard.

- Commanding from the car is done often. Once again, whether it’s right or wrong depends on the situation. The best possible scenario would be to be inside the vehicle, close enough to the scene where you can see the front or, maybe, two sides, with nothing in your line of sight. I can’t remember a time where this was wrong [unless the vehicle is far removed from the scene of a smaller incident (e.g., room-and-contents fire)]. That said, there are advantages to taking command from the car, some of which follow:

- The mobile radio (mounted in the vehicle) is more powerful than the portable radio. Mobile radios can be anywhere from 10 to 25 (or more) watts; portable radios are anywhere from three to five watts.

- The speakers inside the vehicle are louder (and easier to hear) than the single extended mic. This supports the notion that one of the IC’s most important jobs is to answer the radio the first time, every time!

- There are fewer distractions inside the vehicle. This includes ambient scene noise and weather-related distractions.

- This is our “office”; everything we could possibly need is located here. It is also where people will expect to find us.

- Inside the car will be the best place for the command team to handle a Mayday call.

(4) Using later-arriving chiefs as divisions (especially on the interior) is a great way to cut down on radio traffic. A chief who is assigned as an interior division will use face-to-face communications with interior crews. He can then relay critical information, including CAN reports (conditions, actions, needs) to Command.

(5, 6) Commanding from the car offers many advantages including stronger, more powerful radios; fewer distractions; and a better overall listening environment.

Mayday Communications

There are differing schools of thought on how to handle a Mayday call. Some say to run the Mayday (including the rescue) on one channel. Others say to run it on two channels (one for fireground operations and the other for the Mayday operation). The reality is there is no perfect plan. At the end of the day, we can always “what-if” a plan to the point where we believe it isn’t a good one. Ultimately, we must adopt a plan that’s best for our department, that’s easy to implement, and that gives our firefighters the best chance to survive the Mayday.

There are, of course, other factors to consider when training for the Mayday, which include the rapid intervention team, self-rescue, being rescued by other interior companies, and so on. The main focus of this discussion is the communications component of the Mayday plan.

Developing a Mayday Communications Plan

After several months of research and working with our radio shop to better understand the capabilities and limitations of our radio system, we finally came up with a plan. As previously mentioned, we realize our plan isn’t perfect, but we also believe that it gives our firefighters the best chance that their Mayday will be heard the first time and that they will receive the help they need as soon as possible. This plan only works when all players are engaged; this includes dispatch.

We train often, and dispatch is involved in this training. To further build and improve on those relationships, our officers and chief officers spend two hours each year with dispatch in our communications center. We have also begun having our dispatchers ride out with fire crews on an annual basis.

(7, 8) When running command from the car, it’s important to set up in a position that’s out of the way of working crews yet also offers the incident commander a clear vantage point of the scene.

Calling the Mayday

To start, we train our firefighters that anytime they think they might be in trouble (i.e., lost, trapped, or entangled), they should call a Mayday. The first step is to press the “EA” (emergency activation) button on the portable radio. Our radios are programmed so that this action automatically moves the caller from the fireground channel to a predesignated Mayday channel. We also train to keep it simple: No LUNAR (Location, Unit, Name, Assignment, and Resources). Instead, it’s Who, What, Where.

The following actions will help ensure that the following individuals will hear the Mayday:

The BC and BC driver (command technician). They each have a portable radio, but there is also an extra portable radio assigned to the BC vehicle. This third radio stays in the charger (located between the BC and the driver). It is always on and set to the Mayday channel with the volume turned all the way up, 24/7. At a fire, if they get out of the vehicle, they take the extra radio with them. When a firefighter presses the EA button, it causes the BC’s portable radio to emit a high/low tone. This tone alerts the BC that somebody has pressed the EA button and a Mayday transmission should be forthcoming.

Dispatch. When the EA button is pressed, alarms sound on the dispatcher’s console. They can immediately tell whose radio is in EA mode.

Firefighters assigned to the incident. The firefighters assigned to the incident will have their radios on the fireground channel with scan turned on. Our radios are programmed so that if they are on a fireground channel with scan turned on, the radio will ONLY scan the Mayday channel.

Note: When the radio is in EA mode, the firefighter is unable to change channels or turn his radio off. This prevents a panicked or disoriented firefighter from switching channels and ending up on the wrong channel. The only way to “reset” the radio and cancel the Mayday is to hold down the EA button for three seconds. Doing so puts the firefighter’s radio back on the fireground channel.

There are many options for creating a communications plan to prepare for the Mayday. What I’ve listed here isn’t necessarily right or wrong. For my department, it’s the best plan we’ve come up with right now. As we continue to learn from our brothers and sisters across the nation and as technology improves, we will change our plan, if necessary, to better serve our firefighters. At the end of the day, we need to make sure we have a plan—a course of action that will ensure our Mayday is heard and responded to as quickly as possible.

Final Thoughts

As previously stated, communications are not usually the first thing that comes to mind when discussing fireground operations. Typically, they’re only brought to the forefront after the fact. We generally focus on communications during AARs, PIAs, and LODD reports; this needs to change.

Of course, any real and lasting change will occur only when fire department leadership buys in. You know a department has bought in when it creates time in the training calendar for communications training, formally adopts a communications model, and then sets communications expectations for its members. Leading by example has almost become cliché, but when it comes to communications, officers (especially chief officers such as BCs) must realize that they are the ones who most often talk on the radio.

Every time you press that “push-to-talk” button, you are either supporting the department’s communications model and reinforcing good communications behavior or you are sending the message that those things don’t apply, they aren’t important, or you are simply above it all. The point is, we’re professionals. Let’s act like it, especially when talking on the radio. Doing so sets the example for those on scene and even those who are not on scene but listening.

JAIME REYES is a battalion chief with Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue. He is on the department’s training committee and also chairs the fireground communications committee. Reyes is a certified master firefighter and an instructor with the Texas Commission on Fire Protection and a vice president for the International Association of Fire Fighters Local 2149. He has a BS degree from Texas A&M University.