Large fires can be taxing on any fire department, but they can be especially challenging for small-town fire departments that may lack readily available resources to support firefighting operations, emergency medical services (EMS), the incident management system, and a water supply. Small towns often need to rely on neighboring jurisdictions for mutual-aid support, which can sometimes lead to response delays. The 605 Baltimore Street Fire is one example that illustrates some of the challenges Hanover Area (PA) Fire and Rescue (HAFR) faced and how it overcame those challenges.

- Big City Tactics for Small Town Fire Departments: Have a Plan!

- Big City Tactics for Small Town Fire Departments: The Fire Academy

- Big City Tactics for Small Town Fire Departments: Company Preplan Made Simple

Incident

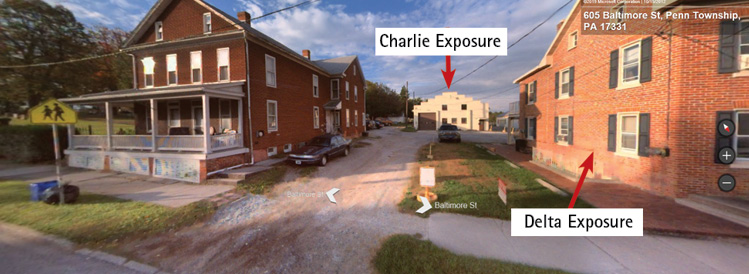

On March 17, 2018, at 1348 hours, the York County Department of Emergency Services (YCDES) received a call for an explosion with a fire and a burn victim. At 1350 hours, YCDES dispatched HAFR to Box 79-03, 605 Baltimore Street, for a residential structure fire with an explosion and a burn victim. Witnesses reported smoke conditions from the structure prior to the explosion. An off-duty firefighter arrived on scene shortly after the explosion and assisted the burn victim (second-floor apartment, Delta-side occupant) to a safe location away from the fire building. The occupant in the first-floor apartment, Delta side, who self-evacuated, stated he was lying on his bed playing on his phone when he heard an explosion and his exterior wall fell into the parking lot. No other occupants were home at the time of the incident.

(1) The two-story semiattached Charlie exposure is at the left. (Photos 1-3 reprinted with the permission of Microsoft Corporation.)

(2) The Charlie and the Delta exposures.

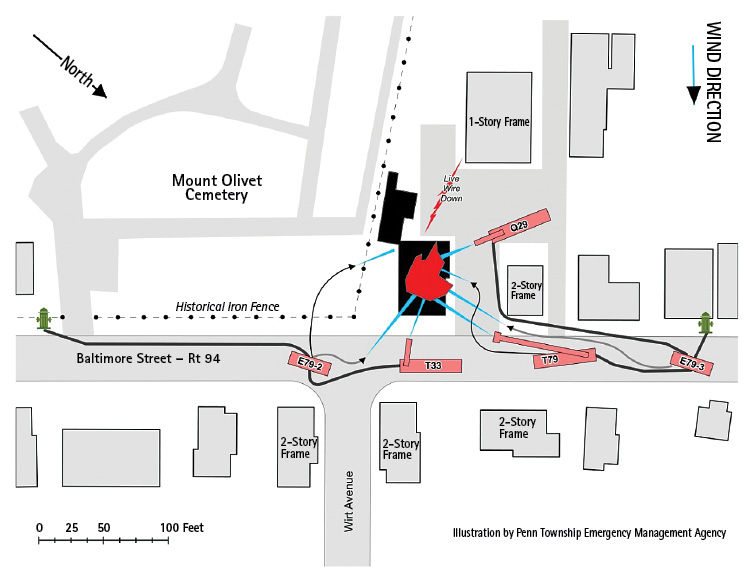

(3) An overhead view of the fire building and the surrounding structures/roadways.

Construction Type

The structure was a two-story wood frame (Type V) with balloon construction; there were open stud wall voids from the ground level to the attic, and there was no fire stopping. The structure dates back to the early 1900s. It is believed to have been constructed as a single-family dwelling; however, over the years, it had undergone renovations to convert the living spaces into apartments. The front gave the appearance of a two-story duplex (two apartment entrances) when, in fact, it was a quadplex (four apartments) with a first- and second-floor apartment along the Bravo side and a first- and second-floor apartment along the Delta side. There were four electrical meters and four natural gas meters present, which helped to confirm the presence of four apartments.

The building was originally covered with wood clapboard siding, which was later covered with asphalt shingles, which esthetically presented as a red brick veneer. The gable roof was covered in asphalt roof shingles. The house faced Baltimore Street and had a cemetery adjacent to the Bravo side; a driveway and an exposure on the Delta side; and a parking lot and two exposures on the Charlie side, one of which was semiattached to the fire structure at the roof on the Bravo/Charlie corner.

The Alpha side presented with a wraparound covered porch that spanned from the Alpha/Delta corner to the Alpha/Bravo corner on the front and down the left side to the Bravo/Charlie corner. Lattice covered the front crawl space under the porch area. There were two center positioned entrances on the Alpha side and two entrances on the Charlie side at each corner of the first floor. There was also a first-floor entrance on both the Bravo and Delta sides. The burn victim removed by the off-duty firefighter was at the Delta side door. A small basement was under the front portion of the house; it likely was used for coal storage back in the day.

The semiattached Charlie exposure was a two-story multifamily residence in which the second-floor porch roof connected to the roof of the fire building. The Alpha side of the exposure had a center exterior stair to the second-floor apartment.

Figure 1. Overhead View of the Incident Scene and General Apparatus Positioning

Weather Conditions

The weather at the time of dispatch was 41° under partly cloudy skies. Winds were from the W/SW at 10 miles per hour; humidity was 0.18 percent. These conditions remained stable throughout the incident. The wind was blowing from the Charlie side to the Alpha side.

Ordinarily, wind can have a negative influence on fire. In this case, however, it is credited with holding the fire toward the Alpha side of the structure and preventing it from advancing toward the rear of the structure and Charlie exposures. Visibility near the Alpha side was limited at times because of the thick black smoke. The wind also aided in maintaining a relatively clear view along the sides and rear of the structure, which would have facilitated vent-enter-isolate-search tactics and ground ladder rescues if conditions and structural integrity permitted.

Initial Dispatch and Subsequent Alarms

At 1350 hours, YCDES dispatched Box 79-03 for a structure fire with an explosion and one burn victim, which included the following first-alarm units responding from quarters: Engine (E) 79-2 (four-person staffing) and E79-3 (two persons), Tower 79-1 (three persons and one ride-along photographer), Rescue 79 (one person), Mobile Air Unit 79 (one person), and Medic 79-1 (two persons).

The following additional units were added since this was designated a “working fire” incident: E52-1 [rapid intervention team (RIT) (five persons)], Rescue 33 (RIT) (three persons), Medics 79-2 (two persons) and 79-3 (two persons), Duty Officer 79 (one person), and recalled paid staff.

At 1353 hours, a second alarm was requested. It consisted of the following: E52-2 (five persons), E53-1 (landing zone) (four persons), E33-1 (five persons), and Quint 29 (five persons).

A third-alarm request at 1354 hours consisted of E 53-2 (five persons), E 29-4 (four persons), and Truck 33 (five persons).

Additional resources included the following: Penn Township Police, Fire Marshal 1 (Pennsylvania State Police), Fire Police 52 (York County), Fire Police 29 (Adams County), emergency management coordinator (Penn Township, York County, PA), York County Department of Emergency Services, York County Mobile Communications/Command Unit (staffing included 911 personnel), Columbia Gas, Met-Ed Electric, Red Cross 1, Red Cross 2, Hanover Water Company, and a demolition contractor.

Situation on Arrival

TW79-1 was dispatched at 1350 hours. One minute into TW79-1’s response, the captain (79F) requested a “Working Fire” assignment followed by a request for a second alarm because of the nature of the call and the heavy black smoke plume seen from the area of N. Franklin Street and Frederick Street. Traveling south on Baltimore Street, TW79-1 arrived first on scene at 1354 hours (a two-minute response time, four minutes from dispatch). TW79-1 found a two-story, wood-frame residential structure with heavy fire on the first and second floors and heavy black smoke moving across Baltimore Street. E79-2 arrived shortly after TW79-1; E79-3 arrived approximately two minutes after E79-2. TW79-1 requested a third alarm at 1354 hours. TW79-1 set up adjacent to 601 Baltimore Street, the Delta side exposure. Both TW79-1 and E79-2 stopped short of the building because of the report of an explosion and the volume of fire and radiant heat on arrival.

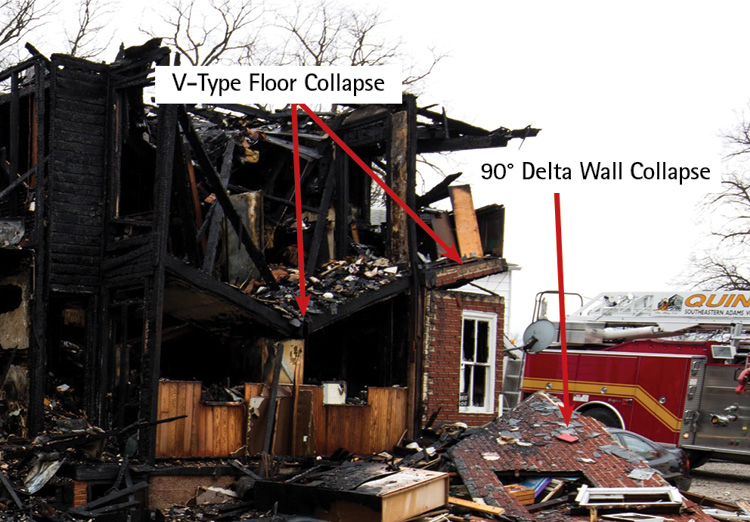

The Delta wall suffered a 90° collapse from roof to ground and was lying on top of an unoccupied parked vehicle. Debris was scattered across the Delta side area.

Because of the wall collapse, the interior rooms were easily visible. Each room, except for the last two rooms on the first floor and the last room on the second floor near the Charlie side, was fully involved. The rooms not involved in fire had heavy black smoke under pressure pushing from them and ignited soon after. The second floor was eventually dislodged at the Charlie/Delta walls by a V-type floor collapse in the Charlie quadrant, Delta side.

After calling for the third alarm, Captain 79F requested EMS to 599 Baltimore Street, where the burn victim was located. Captain 79F established “Baltimore Street Command” in front of the building at the Alpha/Delta corner. Command requested E79-3 to lay a supply line from the hydrant north of the scene on Baltimore Street. Units hand stretched 250 feet of five-inch supply line north of the scene for E79-3 to pick up to supply TW79-1 and themselves on the Alpha/Delta side. E79-2 laid 200 feet of five-inch supply line from the hydrant south of the scene on Baltimore Street in front of Mt. Olivet Cemetery.

Water Supply

The water supply consisted of hydrants on a 12-inch water main that were gravity fed from a reservoir approximately one mile away. The 12-inch water main is a looped system, fed in both directions by 10- and 16-inch mains. The north hydrant provided 1,126 gallons per minute (gpm) and the south hydrant provided 1,300 gpm. The hydrants provided an effective and sustained water supply in which no supply issues were experienced.

Command requested E79-3 to advance a monitor and to supply TW79-1 for aerial master streams. E79-2 deployed a monitor to the Alpha/Bravo side and advanced a two-inch Class A foam attack line to the Alpha side, which was the first water on the fire at 1400 hours (approximately 10 minutes after dispatch and one to two minutes after arrival). E79-3’s monitor attack on the Delta side was initiated next. E79-2 placed in service a second handline on the Delta side. E79-2 focused on fire attack on the Alpha/Bravo sides to cover fire spread near the roof line and to protect the semiattached Charlie exposure. TW79-1 placed two master streams in service from the elevated platform. Recognizing the need to quickly deploy big water through master streams at the onset, the combined efforts of the first-alarm units (two engines, one truck) resulted in rapid control and knockdown of the main body of fire within 10 minutes.

Transfer of Command

Assistant Chief 79-1 (AC79-1) and Captain 79F conducted a face-to-face to transfer command. AC79-1 (Command) assigned Captain 79F as the Operations Division. Operations Division conducted a 360° size-up and noted and reported electrical wires down in the Charlie/Delta area of the building. The Operations Division requested another line from E79-2 to protect the Bravo/Charlie exposure from advancing fire. This line was in place and operating at 1403 hours. By 1406 hours, the main body of fire on the Delta side was knocked down and the fire spreading to the Bravo/Charlie exposure had been stopped. Crews continued working to extinguish pocket fires and to complete overhaul. Structural instability was monitored throughout the incident to ensure the safety of crews. Once the scene was stable, crews worked to salvage and remove personal belongings for occupants from the semiattached Charlie exposure.

(4) The 90° Delta wall collapse and V-type floor collapse in the Charlie quadrant. Note the collapse debris on the parked vehicle. (Photos 4-19 by Harrison Jones.)

T33 and Q29 provided master stream operations and hydraulic overhaul, given the structural instability of the building. T33 was positioned on side Alpha and was supplied by E79-2. Q29 was in the parking area off the Charlie/Delta corner and was supplied by E79-3.

The Mobile Command Unit arrived on scene at 1532 hours. Columbia Gas and Met-Ed Electric were called to the scene to secure gas and electric utilities. The Hanover Water Company disconnected the domestic water service.

EMS Component

An off-duty firefighter who had assisted in getting the 49-year-old male burn victim to a safe area away from the fire building assessed the victim and rendered care, as possible, until the medic crew arrived. The medic crew recognized the seriousness of the burn injuries and requested a medevac at 1400 hours; the estimated time of arrival was seven minutes. Command requested E53-1 to establish a landing zone at the football field near Wirt Avenue and John Street. The patient and patient care were quickly transferred from the ground medics to the helicopter crew. The victim was air lifted to Johns-Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Burn Unit; he had extensive burns to his upper body, both arms, and head. He suffered smoke inhalation and burns to his respiratory tract, making him unable to communicate. The victim was not able to provide details regarding the fire incident before he succumbed to his injuries five days later.

Incident Command System

The incident command system, established early in the incident, was comprised of the following components: incident command; Fire Operations, Alpha/Bravo and Charlie/Delta Divisions; EMS Group; Staging; and Fire/Police Group. A planning meeting was held to coordinate efforts among the Columbia Gas investigation, Fire Operations, and the demolition of the fire structure.

Staging

Responding units, other than those on the first alarm, staged the apparatus on Wirt Avenue and reported with their tools and equipment to stage in front of TW79-1. Command maintained control of staging.

Fire Protection Systems

No fire protection system (sprinklers) existed in the structure at the time of the fire. It was not known if working smoke detectors were present.

Origin and Cause

The origin and cause were undetermined. It has been speculated that the origin of the explosion and fire was the second-floor apartment on the Delta side, between the Charlie and Delta quadrants, which was the burn victim’s apartment and the most severely damaged area. The outward blast suggests the explosion occurred on the interior.

The cause was classified as undetermined after investigators had considered a number of theories, including the following:

- Since the house was supplied with natural gas and had four gas meters, the possibility of a natural gas explosion was plausible. Following the explosion, one suppression company observed that one of the gas meters was missing. Columbia Gas representatives quickly responded to secure the gas utilities and conducted an investigation that showed no evidence of a natural gas-related explosion or problems with any of the natural gas service equipment. Columbia Gas was in the area replacing gas lines a few blocks away from the incident scene as part of a communitywide renovation project.

- One week prior to the explosion, neighbors saw what appeared to be smoke coming from the burn victim’s door. He apparently had a sign posted on the door requesting neighbors not to call the fire department and stating that he was sanding his floors. The dust from the floor sanding presented as smoke to some. Dust explosions can occur when sufficient dust is present and there is an ignition source to trigger the explosion. A portable fan exhausting the dust could provide the ignition source.

- It is possible that one week after the floor sanding, the burn victim may have been refinishing his floors with a floor finish product that offered a flammable vapor. The vapor, mixed with the proper ratio of air, and in the presence of an ignition source, could trigger an explosion and fire.

- Some neighbors suspected for a while that the burn victim may have had an illicit clandestine drug lab (meth lab) in his apartment. However, the investigators did not find evidence of this.

- The investigators also considered attempted suicide. The burn victim was muttering, “Just let me die,” as first responders were attending to his burn injuries. It was not clear whether he said this because he was serious or was in extreme pain from his injuries.

- Neighboring witnesses indicated there was a shadowing of black smoke around the second-floor area, followed by the explosion. This indicates the fire occurred prior to the explosion. One could speculate that perhaps a fire started in the walls or was well advanced in a closed-up compartment and had begun to decay because of a lack of oxygen. Introducing oxygen may have triggered a backdraft explosion followed by a heavy volume of fire.

Sufficient factual evidence was not available to narrow the focus to a particular cause. The burn victim was unable to speak or effectively communicate with investigators because of thermal burns to his respiratory tract and body. Information provided by neighbors and witnesses could not be substantiated. The burned-out structure posed a public safety hazard and was immediately demolished following the conclusion of the investigation.

Lessons Learned/Reinforced

Reinforced

Safety first. In situations where facts are limited, crew integrity and safety must be considered first, second only to immediate line-of-sight and known life safety rescues.

Resources. Request additional resources early to reduce delays and to quickly get personnel and apparatus on scene to support dynamic fire operations.

Water. Big fire requires big water from the start. Even though the structure was a loss, quick deployment of master streams rapidly controlled and contained the fire to the building of origin. The Delta exposure received radiant heat damage along the exterior of the Bravo wall. While engine apparatus were not able to position ideally for deck gun operations, the use of the portable monitors proved to be a highly effective alternative to deliver big water. The two-inch attack handline was also a better initial choice over smaller handlines.

Mutual aid. Established mutual-aid agreements and joint training with neighboring jurisdictions create effective working relationships and streamline operations. Establishing joint standard operating procedures (SOPs) to handle structure fires is an effective method for coordinating efforts among units from different jurisdictions. These SOPs establish duties and responsibilities based on dispatch assignment, which keeps everyone operating from the same page, eliminates freelancing, avoids duplication of effort, and aids in unit accountability.

Proficiency. Effective knowledge of tools, equipment, and apparatus and ongoing training to maintain proficiency are essential for successful fireground operations.

Building construction. Proficient knowledge of building construction aids in quickly identifying the construction type and layout and enables you to anticipate fire behavior within the structure. The fire building was of balloon construction, which allowed fire to burn freely within the walls from ground to attic. The asphalt shingle siding allowed fire to quickly advance along the structure’s exterior walls.

Protection from collapse. When there is an explosion or when the potential for structural collapse exists, maintain effective collapse zones and work within corner safe areas to protect crew members.

Preplanning. Prefire planning and area/building familiarization arm firefighters with advanced knowledge that can be referred to in the early stages of a fire incident—for instance, response routes, positioning and access points, hydrant locations and gpm potential, structure type/use, and available helicopter landing zones.

Preparedness. Anticipate; practice; and prepare for high-risk, low-frequency events.

Effective use of resources. The emergency management coordinator proved invaluable in tracking the residents and confirming who was home and who was not. He obtained witness statements and pictures, identified and triaged potential witnesses while prioritizing those with whom command and investigators needed to follow up, and anticipated the needs of the displaced occupants. Building code officials participated in the decision-making process related to whether the structure should be demolished.

Learned

Maintain calmness. When met with a dynamic incident that involves a high volume of fire, an explosion, and a collapse, firefighters can quickly become excited and overwhelmed. It’s imperative that firefighters recognize this and maintain a calm and cautious approach so they can avoid tunnel vision, maintain situational awareness, and remain focused on the required tasks.

Communications. The incident commander (IC) indicated he was overwhelmed by radio and face-to-face communications at the onset of the incident. The results were that some communications were missed or not effectively followed up. Early command is an integral part of an incident. When command staffing is low, command can quickly become overwhelmed. It is important to assign incoming officers early in the incident to incident management system positions that provide effective scene oversight, accountability, and effective spans of control. With limited staffing, it is important to train candidates so they can take on command leadership roles. An overwhelmed command post can lead to missed fire behavior and trigger event queues, missed structural integrity issues, reduced personnel accountability, and missed or ineffective radio communications. This can be further complicated if a Mayday is called and the RIT is activated.

Evaluation meetings. There is value in conducting command planning meetings to coordinate efforts among all agencies and to reset and move the incident forward as benchmarks are achieved and the needs of the situation change.

Monitor the environment. When an explosion has occurred, consider air monitoring at the onset for lower explosive limits in the immediate area and within surrounding buildings to identify dangerous flammable/explosive vapors that may be present, as well as to establish hot, warm, and cold zones.

Apparatus placement. Consider the route of travel for incoming fire/EMS apparatus and ensure that apparatus placement does not inadvertently block essential apparatus. It would have been helpful to relay the preferred travel route to direct EMS crews to the patient’s location. One EMS unit was blocked in by a fire apparatus and also prevented the truck from gaining an optimal position. EMS units should anticipate their scene positioning and scene exit prior to committing to the block or blocking essential suppression units.

Readiness of equipment. The monitors are stored with the fog nozzle attached. Beginning the attack with the fog nozzle proved inadequate in reach and penetration; the nozzles were replaced with stacked tips. The solid tip nozzle provided effective stream reach and penetration. Crews should consider the most effective nozzle to meet their needs and store this nozzle on the monitor. Also, consider the stacked tip sizes. Master streams are intended for big water application. Consider spinning off the smaller tips to use a larger tip that offers more gpm and effective reach and penetration, as water supplies allow.

Reserve apparatus. Ensure that your crews are familiar with all reserve apparatus. At least one engine and one truck were reserve units. The engine operator was not familiar with the reserve engine, which caused some delay in water delivery and necessitated the help of another firefighter. The reserve truck has a different setup procedure for the jacks and runs slower when the truck pump is in gear. This created delays when truck staffing was split up to cover multiple duties.

First five minutes. Response delays can occur for a variety of reasons. The first five minutes of a fire incident can make or break the incident, so frequent training to address critical factors in the first five minutes is beneficial. Essentially, the actions of the first two engines and truck and early establishment of command got this incident started in the right direction to quickly control and knock down the bulk of the fire with fast, sufficient water.

Situational awareness and demeanor. An incident such as this one can cause firefighters to become overly excited. When this happens, tunnel vision sets in and reduces your ability to focus and to consider the big picture view. When situational awareness is reduced, so is firefighter effectiveness. For instance, one firefighter forgot to bring his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) face piece, which was not stored with his SCBA. Another forgot an essential piece of safety equipment and had to retrieve it before the aerial could be placed in service. These situations lead to delays; avoid them by remaining calm and slowing down to maintain effective situational awareness.

Critical Factors

Size-Up/Situational Awareness. YCDES gave important information on dispatch that supported an effective size-up and anticipation of conditions and actions prior to arrival. The fire and explosion, compromised structural integrity, and electrical wires down required all personnel to maintain an acute sense of situational awareness while working around the incident scene. They also illustrate the importance of establishing divisions to maintain an effective view of all sides of the structure to support command and the operation. The 360° size-up assessment is crucial in identifying the location and extent of the fire, construction type and features, building layout, life safety rescues, additional hazards, exposures, obstacles, and anticipated fire travel. Incident command and company officers must maintain a wide-view perspective and avoid tunnel vision. Some officers did not conduct their own 360o, which may have offered them additional insight.

Water Supply

Community water supply systems can have a variety of characteristics. Work with the water department to better understand these characteristics and to know and understand your community water supply. Preplanning and the use of color-coded hydrants/tops can aid in ensuring that you are using the best water supply for your incident. In this case, responding units understood they were on a looped system that fed from two sides, with two hydrants that provided in excess of 1,000 gpm, so an effective and sustained water supply was available to meet their master stream needs. Crews were also fortunate that they did not have to deal with remote water supplies, drafting, or tanker-shuttle operations.

Incident Command

Establishing a strong, visible, and effective incident command from the start is essential to effective operations and scene control, personnel accountability, a reasonable span of control, resource management, and coordination with other agencies toward unified command operations. Use incoming officers in command staff positions. Train and cross-train personnel to take on command leadership positions, especially when staffing levels can be challenging and response delays are possible. In this case, the mode of operation was defensive, which allows for more command staff to be used on the exterior.

Communications

Responding chiefs who do not have the luxury of drivers/aides can be overwhelmed by radio traffic while trying to drive safely to an incident and paint a picture in their head as information is being received. The need to switch radio channels can also lead to missed or cutoff radio transmissions that cause commanders to have to play catch-up. Radio scan modes can also influence the priority in which messages are heard or not heard. Where possible, the IC should consider establishing the command post at the vehicle, which should have a good visual vantage point for viewing the fire scene without blocking essential suppression units and be readily identifiable to incoming units. Remaining in the vehicle, with the windows up, can help to maintain effective communication by allowing the IC to hear and focus better and to better control face-to-face communications. As the incident escalates, the IC can exit the vehicle and run the incident from the rear of the command vehicle.

While en route to this incident, the TW79-1 captain did not hear AC79-1 verbalize his response or request for the third alarm. Although this was not a significant factor, the captain duplicated the request for the third alarm and recognized how easy it can be to miss essential radio traffic in the first few minutes following the dispatch. Duplicate calls for resources can also create confusion for dispatchers and can lead to additional radio traffic.

It’s easy to eat up valuable radio air time in the front end of an incident when things may seem chaotic. Limit unnecessary radio chatter to essential transmissions so that the IC and the first-in officers are not overwhelmed. Similarly, ICs should not overcommunicate and possibly keep companies from carrying out their operations. Ultimately, the first-in officer sets the tone and direction for the incident. If there are changing conditions or inadequate operational plans, the IC must step in and call an audible to change course as necessary. In fact, incoming officers who identify changing conditions from those reported by the first-in officer should state those changes and recommendations to help ensure operational strategy and tactics remain appropriate for the conditions.

Evolution of the fire: (5) Initial fire conditions on approach at 1354 hours.

(6) The fire at 1355 hours.

(7) The fire at 1359 hours. Monitors are being set up on the Alpha/Bravo and Alpha/Delta corners.

(8) Fire conditions at 1359 hours in the Alpha/Delta corner.

(9) Fire conditions at 1400 hours.

(10) The fire at 1402 hours.

(11) The fire at 1406 hours.

(12) The fire at 1407 hours.

(13) A monitor operating on the Alpha/Delta corner.

(14) The Bravo side at 1417 hours.

(15) The Alpha side at 1423 hours.

(16) The Charlie quadrant collapse area, Delta/Charlie side at 1423 hours.

(17) The Alpha/Delta corner at 1435 hours.

(18) Red brick-style asphalt shingle siding covering clapboard siding, 1439 hours.

(19) An aerial view of the incident scene at 1537 hours.

(20) A postfire view of the Charlie side. (Photos 20-22 by Jeffrey N. Waltman.)

(21) The Delta/Charlie corner postfire.

(22) The postfire view of the Delta side.

Fire Behavior Characteristics

Fire characteristics are often predictable. This incident had a number of variables that intensified the fire. The fire was postflashover before units arrived, so it was in a growth stage and had sufficient air to spread and intensify. The asphalt siding allowed for rapid fire spread along the exterior walls of the structure and produced heavy black smoke conditions that at times hampered line-of-sight visibility.

The collapse of the Delta wall exposed the interior to a continuous air supply to feed oxygen to the fire. A set of natural gas meters was displaced as a result of the collapse, which fed natural gas to the fire until the gas supply could be secured.

The source of the explosion was not evident on arrival. First responders often suspect natural gas as an initial source for explosions in a residential structure. Until the exact cause can be determined, it is important for command to consider all possibilities and ensure proactive actions are taken and additional resources are readily available for mitigation efforts.

Small and rural fire departments can sometimes be challenged by big fires because of limited staffing and resources, water supply issues, and limited practice and familiarity in dealing with high-risk, low-frequency events. The HAFR proved many of the challenges can be overcome through effective training and preplanning. Additional methods to overcome big fire challenges include the following:

- Periodically review current training, staffing, apparatus, and equipment to identify needs.

- Review operational SOPs to ensure they remain accurate and meet modern day fire challenges.

- Periodically review mutual-aid agreements to ensure they are effective, provide effective coverage, reduce response delays, and foster effective working relationships and frequent joint multicompany training initiatives.

- Consider establishing a mutual-aid committee that brings stakeholders together frequently to discuss operational considerations for each jurisdiction.

- Consider developing common SOPs that govern emergency operations involving mutual-aid jurisdictions. This keeps all companies, regardless of jurisdiction, operating from the same SOPs, based on dispatch order, as opposed to different companies operating from different SOPs on the same fireground.

- HAFR units quickly acknowledged the scope of this fire and rather than come off with small lines from the start, they recognized the need for a defensive operating mode with big water. Company officer decisions in the first five minutes to call for additional assistance and to establish incident command got the ball rolling in the right direction.

- The portable monitors provided an effective alternative, since the situation and conditions prevented optimal positioning for the use of deck guns. The monitors allowed for quick deployment and operation. Pulling two-inch handlines and flowing high-volume water with foam helped to quickly cool surfaces and suppress flames. Aerial ladders were quickly and effectively positioned to apply additional master streams. Supply lines were put on the ground, and the looped hydrant system provided an effective and sustained water supply to easily support all the master streams and handlines. The wall collapse opened the compartment where the fire was, which allowed streams to be applied directly to the flames. Use the proper strategy and tactics for the call you’re on and get sufficient water on the fire as quickly as possible, regardless of where it comes from.

Author’s Note: Thanks to Hanover Area Fire Rescue for sharing its experience on this fire incident so that others may learn and benefit.

Nick J. Salameh is a 36-year veteran of the fire service. He was a fire/emergency medical services captain II and previous training program manager for the Arlington County (VA) Fire Department, with which he served 31 years. He is a former chair of the Northern Virginia Fire Departments Training Committee and a former volunteer firefighter for the Fairfax County (VA) Fire and Rescue Department, Bailey’s Crossroads Fire Station 10. He is a contributor to Fire Engineering and Stop Believing Start Knowing.