fireEMS ❘ By Bryan Fass

My guess is that very few of you became firefighters to run emergency medical services (EMS) calls. Yet, as you already know and as the data clearly show, between 55 and 70 percent of all calls are for medical-related issues. According to the International Association of Fire Fighters, more than 50 percent of all line-of-duty injuries and 50 percent of all early (medical) retirements are the result of soft-tissue injuries.

Let’s face it, training for EMS duties is not nearly as cool as training on the fireground. Maybe that’s why training for handling patients is never done. Most EMS runs follow a somewhat predictable pattern and, as you know, predictability is a good thing if we capitalize on the opportunities it provides.

Causes of Injuries

Let’s explore sources of the majority of EMS injuries. We see injurious forces on the body exceeding National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommendations when the following actions occur:

- Lifting directly off the floor places the highest amount of load on the spine, in excess of what your body can handle. Think of it this way: Picking a 220-pound person up off the floor on a spine board or combi board places more than 3,500 pounds of compressive force on your spine. We know that injury occurs when loads exceed 1,700 pounds. 1,2,3

- Flexion and rotation are career enders. We call twisting and leaning forward “back death.” It occurs when you and your partner put the patient onto the cot or a bed, especially when you are carrying the patient and you have to “sling the patient onto the cot.”

- Friction is the most obvious and the easiest to fix, sort of. How do you move patients from stretcher to bed? If you said with a bed sheet or a draw sheet, then your culture is stuck. What device (that you probably have) can reduce friction and limit how far you lean over the bed to move the patient? Yep, those soft stretchers used for bariatric calls need to be used for all patients. In fact, when deployed and used properly, they also change your lift height from the floor, which puts us back in line with NIOSH standards.

- The stretcher is still a problem, and it really should not be. With the advent of modern powered stretchers, there is no reason for a single person to load and unload the stretcher. Yet, we see injury to the shoulders, neck, and arms occurring time and time again because a firefighter decides he can lift and load the stretcher alone. Folks, powered cots are never to be loaded and unloaded by a single person. If your department is still using manual stretchers, that is fine; they are still a good option for some services. But, treat your manual stretcher like its modern cousin and have two people load and one person on the carriage.

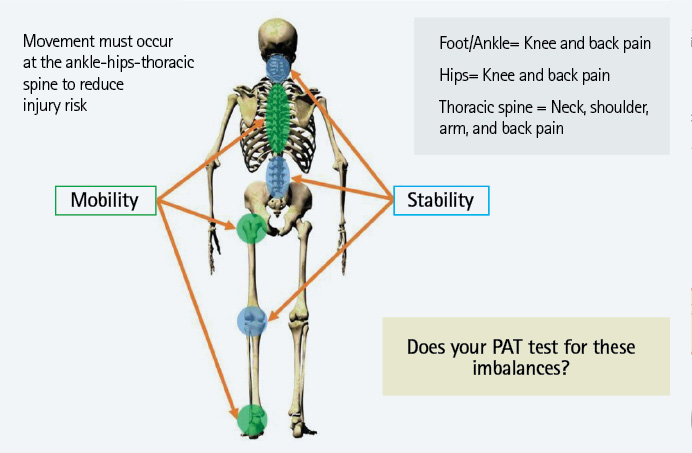

Figure 1. Mobility vs. Stability

It’s Also a Movement Problem

It matters not only how you move the patient but also how well you move the patient. Having written and validated no fewer than six physical abilities tests for EMS and fire, I had to look at a lot of biomechanical data. This will seem like common sense to some of you; the ability to squat, lunge, step, and deadlift are the most critical movements in the job.

The rub is this: How many of you and your departments focus on both mobility work and strength training for these critical movements? As I teach in all my train-the-trainer classes, “I can’t teach you to move patients well if you can’t move well.”

How much time on each shift is devoted to job-specific mobility training as a crew? I strongly advocate for at least five minutes. Five minutes out of 1,440 minutes is nothing. Plus, after some job-specific mobility work, not only will you feel better, but you will decrease your risk for soft tissue trauma.

Take it a smidge deeper: Biomechanical injury occurs at the ankles and calves, the hips, and the upper back. Again, falling into the predictable-is- preventable category, you can build in mobility work and strength training to target the “why” of firefighter injury.

Mobility and Strength-Training Exercises

Following are some maneuvers that can enhance mobility and build strength:

Mobilize the ankles and calves. Use the foam roller. Learn the calf and ankle glide drill. Allow your crews to wear sneakers in the station (this helps the ankle and foot move more freely).

(1) A common career-ending move. (Photo courtesy of Fit Responder University.)

Keep those hip flexors loose. As sedentary as our profession/society has become, coupled with all those dangerous academy exercises (leg raises, scissors, feet hovers, sit-ups), we have effectively malaligned the hip flexors. When they are too tight, they mess up the balance in the pelvis, and guess what? You end up using your back as a prime mover and overrely on the knee instead of the glutes to get mechanical power.

Thoracic extension is key to keeping the torso safe. Life, technology, self-contained breathing apparatus, and phones all contribute to the down and round/head forward posture we see in society. It’s also one of the reasons that we are seeing so many shoulder and neck injuries in the service. Firefighters must build thoracic mobility and rotation drills into their daily injury-prevention training. Plus, your fitness trainers must program extensor chain dominant sessions where your crews are doing at least two pulling motions (row, reverse fly, pull up, dead lift, for example) for every push exercise. Keeping the posterior chain very strong [traps (all three heads), paraspinals, glutes, hamstrings] and the thoracic spine mobile is one of the most important parts of the biomechanical picture.

Putting It into Practice

Late last year, I had the honor to work with a mid-size fire department in Oregon. This service, like many, runs a lot of EMS calls; it transports at the advanced life support level. It also has a fair number of fire-related calls. Injury rates were spiraling out of control. Fitness time was recommended but not mandatory; for some reason, it does not do any of the National Fire Protection Association 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, based annual testing. Admittedly, this is a lot to fix.

Step 1: Stop the bleeding. I determined that reducing line-of-duty injuries was the key for this department. It has purchased, trained on, and deployed two different patient-handling tools (both under $40) that will allow members to change lift height, reduce flexion/rotation, and eliminate friction. They all went through the Fit Responder Injury Free online course, and their trainers showed them how it makes their job easier.

Step 2: During the patient-handling training, many of the firefighters will realize that they no longer possess the physical ability to squat or lunge properly. This is the perfect time to introduce some mobility drills because it hits them with the “why” and not just the “we should.”

Step 3: Check off the truck, then check off your body. Coffee is not an injury-prevention tool. After their apparatus and gear checks, their station trainer, with the backing of the line officer, leads all of the crew through a five-minute mobility series with the clear understanding that it prevents injury and improves career longevity. It’s not fitness; it’s injury prevention.

What I have learned over the years is that when I can give the “why,” take away the pain with proper mobility work, and improve career longevity while reducing line-of-duty injuries, then the often elusive firefighter fitness programs are not such a hard sell anymore—not that surviving the job needs to be sold, but that is the world we live in.

References

1. Oregon OSHA. Firefighter and Emergency Medical Services Ergonomics Curriculum, www.cbs.state.or.us/osha/grants/ff_ergo/index.html.

2. McGill, S. “Low Back Disorders.” 2007, Human Kinetic, 218-222.

3. Preliminary Evaluation of Human Factors and Ergonomics in a Novel Backboard Design (EZ Lift Rescue System) for use by Emergency Medical Personnel. Stephen Swanson, M.S., Principal Investigator: The Orthopedic Specialty Hospital, Sports Science and Medicine Laboratory. Murray, Utah.

Bryan Fass, ATC, LAT, CSCS, EMT-P (ret.), has dedicated the past 10 years to changing the culture of fireEMS from one of pain, injury, and disease to one of ergonomic excellence and provider wellness. He has leveraged his 15-year career in sports medicine, athletic training, spine rehabilitation, and strength and conditioning and as a paramedic to become an expert on prehospital patient handling/equipment handling and fireEMS fitness. His company, Fit Responder, works nationally with departments to reduce injuries and improve fitness for first responders.