By LEIGH H. SHAPIRO

Whether you are a company officer or an incident commander (IC), you will inevitably be faced with challenges that have the potential to stop you in your tracks. Having been around a few years myself, I have learned to respect three types of fireground failures that tend to occur frequently and have propelled my crews and me into a creative problem-solving mindset so we could complete our mission. Firefighters thrive on professional challenges; just look at the number of training publications, seminars, and classes designed to address these issues. What information is offered in this article that you cannot learn elsewhere? Well, these three fireground failures are so commonplace that they are perceived subliminally and may not register on our radar screen—until we recognize the pattern.

Failure #1: The Plan

World War I German military strategist Helmuth von Moltke aptly stated, “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy”—and he was right! Most of the time, a derivative of a stated plan works just fine; but, overall, plans do not typically go as they were intended. For this reason, use a plan as a guideline instead of as a strict game plan. When you arrive on the incident scene, just the fact that you need additional resources or alarms is an indication that the initial action plan needs revision.

Although it is absolutely necessary to maintain standard operating guidelines, procedures, and directives, do not allow yourself and your objectives to get locked into a set plan that did not or could not have considered the unexpected, unintended, or unwanted jolts of reality. It is equally imperative to be dynamic in your thought process by constantly performing an ongoing size-up and contingency planning. Ensure that the inevitable question, “Now what do I do?” is answered with a Plan B. Through consistent reevaluation of the situation, even after fire knockdown, the questions “What do I have?” “Where is it going?” “What do I need?” and “What could go wrong?” are readily anticipated.

(1) Companies arrive to find the structure well-involved, forcing an immediate plan revision. (Photos by author.)

Failure #2: Technology

Technology, in all its glory, will inevitably fail likely when you need it the most. As the fire service evolves, so do complacency and laziness; we’d all love to have “an app for that.” Unfortunately, our job still needs to get done; the following statements (usually stated in the heat of the moment) are all too familiar to firefighters: “The dispatch info is wrong”; “The radios are junk”; “The computers are slow”; “The thermals are old”; “The meters are off”; “The batteries are dead”; “The saw won’t start”; “It worked earlier” (my personal favorite), and so on. How many times while responding to or operating on the fireground have you muttered these statements or heard them so eloquently applied as the reasons something didn’t go as planned?

Overreliance on personal protective equipment and electronics (fancy gadgets and gizmos) has led to a reduction in critical thinking and a suppression of the core senses, leading to disastrous fireground situations that are completely preventable. Even cavemen figured out how to deal with fire; so, what’s changed? Technology—whether it’s thermal imaging cameras, encapsulating turnout gear, or computers—should be used for their intended purpose, to assist and accentuate, not replace! Be ready for that old-school firefighting of using your training, your experience, and your “gut” (intuition) to guide you, and let the technology be what it was intended to be—another tool in your toolbox.

Failure #3: Initiative

Instead of operating as you originally planned, your actions have now transitioned into playing catch-up at the incident because you lost your initiative and now have to do something different. Why? Because what you thought was a definite is wrong; what you believed was going well is not; what you were initially told is inaccurate or incomplete; what you thought would not happen just happened; equipment and people you depended on were not reliable; tools and crews did not perform as expected; the fire may get bigger, not smaller; the structure may weaken to the point of compromise; needed resources may not be available; or, the ultimate kicker, someone calls a Mayday!

This all ties back into what I stated earlier about anticipating these potential issues and having alternative plans in place to address them. The basic strategy remains largely the same, but the tactics must adapt (in real time) to what is happening. Eventually, you will get to where you want to be, but not expecting the unexpected is the surest way to bring everything to a screeching halt. More importantly, however, are recognizing and overcoming these failures to effectively and efficiently complete your mission.

The Point

You may not have heard of these three fireground failures placed in this context before or, more likely, you never consciously realized how these simple things can undermine an operation, but “when you spend more time fixing tools rather than fixing the car,” as my father used to say, you begin to see the pattern, which becomes frustrating and unnerving. This is the part of the job of a company officer or an IC that seems to always happen in one form or another, but it is often forgotten about at the “successful” conclusion of an incident because the job got done and we mentally categorized these occurrences as incidental. By ignoring or failing to address the root cause, we are potentially setting ourselves up for future failures. This oversight can eventually lead to a more severe or even tragic outcome.

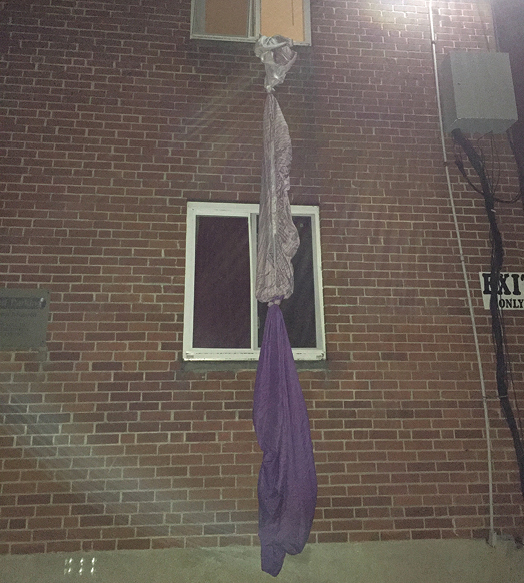

(2) A citywide radio failure prompted this error message while en route to an incident. (3) Residents tied bedsheets together to create an escape route out the back of the building during an apartment fire.

Just because the presumptions of plan implementation, functional technology, and initiative priorities are set in motion but don’t go as expected doesn’t mean you’re out of the game. You just have to evaluate the situation and adjust accordingly. The fireground is a highly dynamic environment; therefore, we must remain aware of our surroundings and be flexible.

During the World War II invasion of Normandy, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. found that his division’s landing crafts had drifted south of their objective, placing the first wave of his men a mile off course. As they approached the beach, he assessed the situation and chose to fight from their current location rather than to attempt to relocate to their intended position. He stated, “We’ll start the war from right here!” The ability to adapt, improvise, and overcome unanticipated adversity is critical to mission success—and it’s what we do best!

LEIGH H. SHAPIRO, MS, is a recently retired deputy chief/senior tour commander from the Hartford (CT) Fire Department, where he served 28 years on the line. During his tenure, he was a firefighter, a lieutenant, a captain, and an interim assistant chief/deputy director of emergency management. He now operates a fire service consulting firm and is a guest lecturer on fire service leadership.