By Jaime Reyes

Having reliable communications on the fireground is critical to the safety of all firefighters on scene. Dependable communications start when your shift starts. They begin with the daily check of your radio and progress throughout the shift. Each of us plays a role in the overall quality of our department’s communications, and constantly working to improve communications should be our top priority. Almost any drill, whether it is individual, company level, or multicompany, can and should include a communications component. How often are we pulling lines and throwing ladders? Why not start the drill by pulling up in the rig and giving a size-up over the radio? Continue the drill by communicating as you would on an actual scene. This is just a small way we can begin to improve the communications process. Like anything else we do, it involves muscle memory; so the more we do it, the more automatic it becomes and the more comfortable we will be using our radios. Keep in mind that one of the main goals is to create open, available airtime and that any change we make, no matter how small, could have far-reaching and beneficial results.

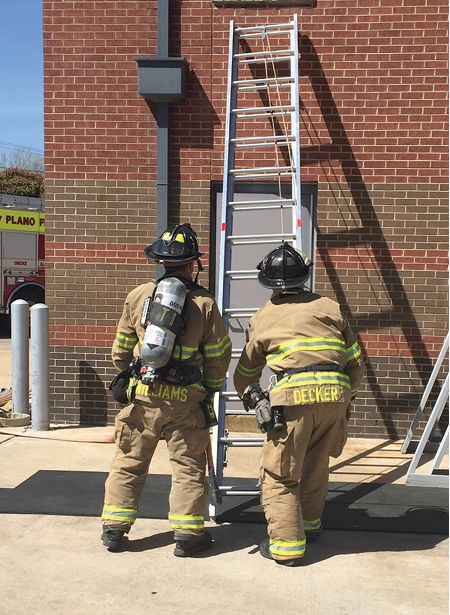

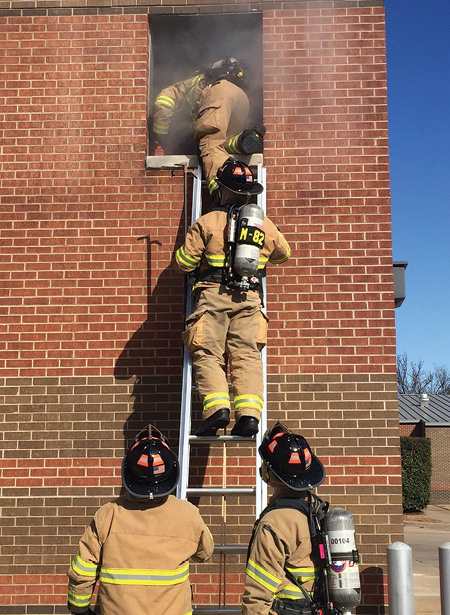

(1-4) Company-level drills are excellent times to incorporate a communications component as part of the overall training. This is often overlooked, but it’s a great opportunity to practice and improve our communications. (Photos by author.)

Getting Started: Making a Plan

In 2013, my department conducted its first ever strategic planning session. I was assigned “fireground communications” and was asked to identify any communications issues our firefighters were experiencing. Although we had many people carry that torch over the years, we finally had the backing and support of our chief. Everything was on the table. I was looking to identify problems or issues with equipment, the radio system, radio programming, and any necessary training we were lacking. It wasn’t long before I quickly realized that I needed help. As a result, we formed a “fireground communications committee.” This committee included representatives from operations, training, logistics, dispatch, and our radio shop. One of the first things we did was to contact other departments, including Phoenix, Arizona, and Fairfax County, Virginia. We gained much valuable information and the committee quickly made several recommendations, which the department adopted almost immediately. We continued to research, learn, and make changes. The early results showed that we were improving our communications. However, we weren’t ready to pat ourselves on the back (nor are we doing so now); the reality is that we still have lots of work to do.

Problems Identified; Changes Made

The committee identified several communications issues. This was no surprise to anyone. The most critical issues included too much talking, unreadable transmissions, and too much radio traffic from dispatch. We addressed each area as follows.

Too Much Talking

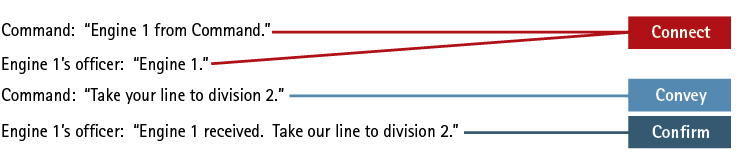

We instituted departmentwide training that included the adoption of a new communications format known as “the 3 Cs”—Connect, Convey, Confirm. This 3 C format is a modified version of Mark Emery’s 4 C model used in Fairfax County [Emery is the chief of the East Valley (WA) Fire Department]. Of the 3 Cs, the most important component is the first “C,” Connect. If we get this right, the other “Cs” seem to fall into place. A good example is Command calling Engine 1. It looks like this (see below).The “Connect” happens when Engine 1’s officer replies, “Engine 1.” Most in our department were accustomed to replying, “Go ahead.” The issue here is that if the reply is, “Go ahead,” the connection hasn’t been made. In this example, Command called Engine 1. What if Truck 1 thought Command was calling them and they replied, “Go ahead”? If that happened, it’s easy to see how a communications breakdown could occur. Command called Engine 1. When Engine 1 replied, “Engine 1,” Command knew for certain he has connected with Engine 1.

If you’re implementing this policy in your department, stress that all communications need to follow this format. If you use the same communications format on every call (yes, even medical or nonemergency calls), then it will become second nature and you won’t have to think about it. The 2 a.m. structure fire isn’t the time to be changing the way you communicate on the radio.

Size-Up (clear and concise). Our committee addressed the problem of “too much talking” by stressing the need for concise transmissions. If the goal is creating more available airtime, our radio transmissions need to be concise. This is especially true during size-up. Our biggest change here was to simplify things a bit. For example, somewhere along the way, we complicated our size-ups by not using plain speech. It was not uncommon to have a size-up like this: “Engine 5’s on scene. We’ve got a two-story single-family residential structure, comp over brick, smoke showing from the C side.”

Since when did we make things so complicated? Let’s just call it what it is. How about this instead? “Engine 5’s on scene of a two-story house; smoke showing from the Charlie side”? Along with calling a house “a house,” you’ll also notice that the second size-up used the phonetic alphabet “Charlie” as opposed to “C.” This wasn’t new for us, but it is something we identified as an issue and we’ve been including it in our training. Keep in mind, “B” sounds a lot like “D” and even a little like “C,” especially when spoken over the radio.

Another thing to keep in mind during the size-up is that when the first crew on scene gives a size-up, Dispatch often repeats it. Therefore, a 10-second size-up will result in 20 seconds of radio traffic. We need to get the information out, but we can do so in a clear and concise manner.

A final thought on the size-up is to keep it simple. The purpose for the size-up is to let others know what you’ve got. They’ll get more information from you after your 360° walk-around (360).

Situation Report (given after the size-up). Once the first apparatus on scene has given its size-up report, the officer will complete a 360 and give a “situation report” to the first-due battalion chief whether he is on scene or not unless Command has been established. In that case, the situation report would be given to Command. This is done to prevent Dispatch from repeating it as it does the size-up. The situation report should contain the following key items:

• Confirmation that the 360 has been completed or, if not completed, the reason it was not done.

• An updated size-up that includes any other pertinent findings.

• Occupant status (if known).

• An incident action plan (IAP). Tell others what you are doing and what needs to happen next. Consider taking command if the battalion chief will be delayed and it’s necessary to complete the IAP.

A situation report should sound like this:

Engine 6: “Battalion 1 from Engine 6, Situation Report.”

Battalion 1: “Battalion 1.”

Engine 6: “360 complete; heavy fire from the garage. Homeowner states all occupants are out of the house. Engine 6 will blitz the garage. Need the next-in engine to bring us water.”

Unreadable Transmissions

Next, our committee addressed the issue of “unreadable transmissions” by going back and reviewing the International Association of Fire Chiefs’ best practices along with our radio manufacturer’s recommendations. This included holding the mic one to two inches from your mouth and using your body to shield background noise created by apparatus pumps, ventilation fans, and saws. With the assistance of our radio shop, we took things a step further and conducted background noise-suppression testing. We tested while a group of evaluators listened remote from the testing and graded each transmission. Based on the results of these tests, the radio shop was able to customize the background noise-suppression settings in our radios and remote speaker mics.

Too Much Radio Traffic from Dispatch

We addressed the issue of too much radio traffic from Dispatch in a couple of ways. First, we developed a training class specifically designed for Dispatch. The class included Mayday training as well (more on that later).

We made several changes based on information obtained from Fairfax County. The biggest change included setting up a Command Channel for working fires. As previously mentioned, one of the goals for conducting this training was to create available airtime. We realized that any change we made, no matter how small, could potentially have far-reaching and beneficial results. The Command Channel is a great example.

(5) The orange EA button can be custom programmed based on department need. In this case, it’s programmed to move a firefighter to a predetermined Mayday channel when the button is pressed for one second.

This is how it works: At the onset of a working fire (and when staffing allows), Command calls Dispatch advising them to “open the Command Channel.” From this point forward, all communications from Dispatch are conducted on the Command Channel. This includes everything from time checks to giving estimated time arrivals for utility companies, investigators, additional companies, and so on. Once the Command Channel has been established, the only people talking on the Fireground Channel are Command and fire companies assigned to the incident. A chief’s aide, a driver, or a similar party monitors the Command Channel. At no time should one person (i.e., Command) have to monitor both the Fireground and the Command channels. Command should concentrate only on communicating with fire companies on the Fireground Channel.

(6) Shown is a method of attaching the remote speaker mic to the helmet by an elastic loop. The loop holds the mic in place, making it easier to hear communications and reduce the likelihood of missing critical transmissions. It also is easier to place a hand on the mic since the mic remains in one spot.

The Dispatch class, taught annually since 2014, has been beneficial in establishing lines of communication and getting Dispatch’s perspective on certain incidents and call types. It’s a great opportunity to share information, and I look forward to it every year. These relationships are important for many reasons, especially for training for the Mayday. If the unthinkable happens, Dispatch will be right alongside us doing its part to help us rescue our brothers and sisters. The fire service trains for the Mayday; there’s no reason our partners in Dispatch shouldn’t be included in that training.

Mayday Communications

Few topics get a firefighter’s attention more than the Mayday—specifically, in this case, how communications should be set up for a Mayday. There are differing schools of thought on how a Mayday should be handled. Some say that the Mayday (to include the rescue) should be run on one channel. Others say it should be run on two channels (one channel for fireground operations and the other for the Mayday operation). This was discussed at length in our committee and throughout the department.

My experience has been that no matter what plan we looked at, no matter how foolproof and simple we tried to make things, at the end of the day I could always find a “what if” that led me to believe we didn’t have a good plan. Ultimately, we have to adopt a plan that’s best for our department, workable, and gives our firefighters the best chance to survive the Mayday. There are many other important related topics including the rapid intervention team, self-rescue, being rescued by other interior companies, and so on. Those items are outside the scope of this article.

After several months of research and working with our radio shop to better understand the capabilities and limitations of our radio system, we finally came up with a plan. As previously mentioned, our plan isn’t perfect, but it gives our firefighters the best chance that their Mayday will be heard and they will receive the help they need as soon as possible. This plan will work only if all players are involved (including Dispatch) and we continuously train.

The Plan

If the firefighter thinks he might be in trouble, he should call the Mayday:

• The firefighter thinks he’s in trouble (lost, trapped, or entangled). He presses the “EA” (Emergency Activation) button on his portable radio.

• This action automatically moves him from the fireground channel to a predesignated Mayday channel, where he calls his Mayday. We train to keep it simple: No LUNAR. Instead, it’s Who, What, Where.

• The following individuals hear the Mayday:

- 24/7

• When the radio is in EA mode, the firefighter is unable to change channels or turn off his radio. The only way to “reset” the radio and cancel the Mayday is to hold down the EA button for three seconds. This also prevents a panicked or disoriented firefighter from switching channels and ending up on the wrong channel.

Other Options

Running the Mayday and Fireground on One Channel

A firefighter calling the Mayday may become disoriented, confused, panicked, or all of the above. It has already occurred in the past that the firefighter presses the PTT (push to talk) button and keeps holding it down. In doing so, he locks up all communications on the channel and for the entire incident. If the Mayday were being handled on the one channel, this could be disastrous. We did not choose this option for our plan because of the possibility of this scenario occurring.

Running the Mayday and Fireground on Two Channels

Another alternative we researched was handling the Mayday on two channels—fire operations on one and the Mayday on the other. Most would probably agree that the Mayday firefighter should not be manipulating his channel selector. In the case of a Mayday, the incident commander (IC) would move fire operations to another channel, leaving the Mayday firefighter on the original channel.

The issues brought up included the following: How certain would it be that all firefighters would successfully switch to the other channel? When the IC announced that fireground operations were moving to another channel, what if the Mayday firefighter was confused and tried to switch channels?

Dr. Richard Gasaway, an expert on human error, referenced a study in which a Mayday drill was conducted. The IC moved fireground traffic to a different channel. As the drill progressed, firefighters were occasionally switching their radios back to the Mayday channel to check on the progress of the rescue. This caused them to miss important radio traffic on the fireground. It’s easy to see how this could happen during an actual rescue.

There are a multitude of options when it comes to creating a communications plan to prepare for the Mayday. What I’ve listed here isn’t necessarily right or wrong. For my department, it’s the best plan we’ve come up with right now. As we continue to learn from our members across the nation and as technology improves, we will change our plan if it’s needed to better serve our firefighters. At the end of the day, we need to make sure we have a plan, a course of action that will ensure our Mayday is heard and responded to as quickly as possible.

Jaime Reyes is a 20-year veteran of the fire service and a captain with Plano (TX) Fire Rescue, where he is assigned to Truck 1. He is on the department’s training committee and chairs the Fireground Communications Committee. He is a certified master firefighter and instructor with the Texas Commission on Fire Protection. He is a vice president for the International Association of Fire Fighters Local 2149. He has a B.S. degree from Texas A&M University.