BY ROBERT FINGER JR.

Firefighters may be called to perform ultra-hazardous, unavoidably dangerous activities every time they answer a call, whether it is going to an alarm or a technical rescue. Fire departments must ensure their members are trained and possess the skills and abilities to safely perform the tasks.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Program, states, “The Fire Department shall establish and maintain a training and education program with a goal of preventing occupational deaths, injuries and illnesses.”

When designing your training program, identify the causes of deaths and injuries and the skills and knowledge necessary to prevent them. The training officer and the chief officers are, in fact, developing a risk management plan that identifies the associated risks and describes ways to prevent illnesses, injuries, and deaths. When a department creates a risk management plan, it satisfies the NFPA 1500 standard as well as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) 1910 standard.

Risk Management Plan

Designing your risk management plan necessitates that your department look at a number of things. First, consider what it is truly capable of doing. For example, hazardous materials incidents are potentially very high-risk but low-frequency events. Firefighters and fire officers may not be experienced enough to safely carry out an operation. Although this is an essential public service, most departments around the country do not have the personnel, the equipment, or the time to regularly train on safely handling all aspects of a hazmat incident. This is not necessarily a failure or a shortcoming. The department’s leadership has just decided not to expose its members to a hazard they cannot handle safely.

Second, examine the response area’s needs. A fire department should not spend its valuable training time on high-rise and standpipe operations if its primary response area features only one- and two-story residential structures. The risks involved in fighting a fire in a Type V (lightweight construction) building are not the same as those involving fighting a fire in a 20-story fire resistive building. Although each is important, the risk management plan should place more weight on single-family dwelling fire behavior and focus its training plan on that area.

Every fire department should consider what its members do for a living. In a department in which many of the members work with machinery and power tools, it may not need to emphasize training on how to start and operate a saw or portable pump. Although it should not minimize tool safety instruction, the training program should focus on tasks members may not encounter every day.

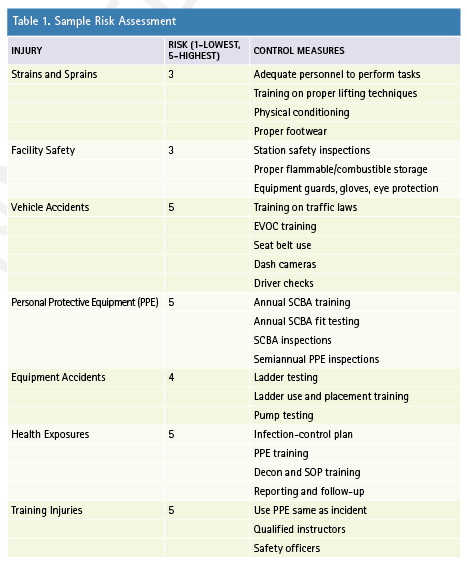

Firefighting has some obvious associated risks, including thermal injuries; sprains, strains, and fractures; falls from heights; objects falling from above; and many others. Risks that are not as obvious include traffic accidents, violent persons, and bloodborne pathogens. The risk management plan must identify and include each of these risks. Once identified, assign each risk a value or severity rating. The greater the risk, the higher the value that should be assigned. When the risks have been identified and rated, institute control measures for managing each one. The risk management plan provides guidance in developing a training program for your firefighters (Table 1).

Personnel Analysis

“The Fire Department shall provide training and education for all department members commensurate with the duties and functions that they are expected to perform.” (NFPA 1500 5.1.2.)

(1) Each firefighter must have the tools and equipment required for his task and be ready with the officer at the entry point. (Photo by author.)

Not everyone in a fire department is capable of going in or wants to go in a burning building. As you develop the risk management plan and look at your members’ makeup, ask each member what role he wants to play in your fire department. The training officer and the chief officers need to look at each member and decide whether they should allow certain members to take those roles. If a member is not comfortable working at heights, that person should not be part of the roof team. Putting the individual in that situation is a recipe for an accident. With proper training and experience, the firefighter may become comfortable working at a height, so personnel evaluation must be ongoing.

SOPs

Fire department leaders should set a standard for what they want the members to be able to do by developing core competencies. They would include such tasks as connecting to a hydrant using a consistent department method, pulling a crosslay hose, or throwing a ladder. Seat assignment is the most basic core competency. Members need to know the type of alarm to which they are responding and in which seat they will ride. Based on the seat assignment and the alarm type, a firefighter knows what he is expected to do and what tools and equipment he is expected to retrieve before meeting the company officer at the point of entry. You can practice this during drill time (photo 1).

Establishing standards allows the fire department leadership to build better written procedures. NFPA 1500 states, “The Fire Department shall provide all members with training and education on the department’s written procedures and guidelines.” With the risk management plan in place and standard operating procedures (SOPs) established, building your department’s training plan can be easy.

Conversely, if the SOPs are not your department’s strong suit but your training program is, you can easily document what you are doing in training as an SOP or Best Practice document. Training and SOPs work very closely together, and some SOPs may be enhanced or altered after finding better ways to perform tasks while training [see “Manlius (NY) FD Best Practice (Excerpt)” sidebar].

Lesson Plans

Departments may have several instructors. Having the training officer develop lesson plans will ensure that all instructors convey a consistent message. Lesson plan objectives must be clearly written and include the following components:

1. The target audience (e.g., interior firefighters, apparatus operators).

2. The purpose of the lesson.

3. Under what circumstances the training will occur.

4. What the participants will be able to accomplish.

5. The standard used to evaluate training success.

6. The materials and equipment needed.

7. The citation of a written departmental procedure.

A lesson plan need not be complex. It should outline the information to be presented, the information’s source, and how to present it. Including these elements ensures the delivery of consistent information and provides each instructor with a tool that describes the best means of presentation. Also, it is an excellent reference whenever instructors and members may have to answer questions that arise [see “Manlius FD Lesson Plan (Excerpt)” sidebar].

Building a fire department training program is not an insurmountable task. Often, most of the work is already completed; the pieces just need to be assembled. It is all about looking around your department and evaluating the personnel and the response area and developing a risk management program based on those findings. The training officer can then use that program to develop a training schedule that addresses the high-risk tasks or conditions while emphasizing the control measures put in place. Use an SOP as the foundation for each drill. Lesson plans will ensure that the training division director and training officer deliver a consistent message.

ROBERT FINGER JR. is a 20-plus-year veteran of the emergency services. He is a lieutenant with the Manlius (NY) Fire Department. He is a municipal fire instructor, paramedic, and certified instructor coordinator with the New York State Bureau of EMS. He has a BS degree from the State University of New York Health Science Center at Syracuse and has been teaching firefighters and EMS and health care workers for most of his career.