By Dane Carley and Craig Nelson

An even better example is a project between the Pittsburgh Bureau of Fire and Carnegie Mellon University’s Smart Cities Initiative . This project involved Pittsburgh providing data to college students who converted it to predict a commercial building’s risk of fire. The risk rating informs the Bureau’s fire inspectors so they can inspect the buildings at highest risk of fire since there are not enough personnel to inspect all of them according to Levine . This makes the Bureau more efficient because inspectors focus their energy on the buildings in the most danger and more effective because the outcome is a reduced loss of life and property.

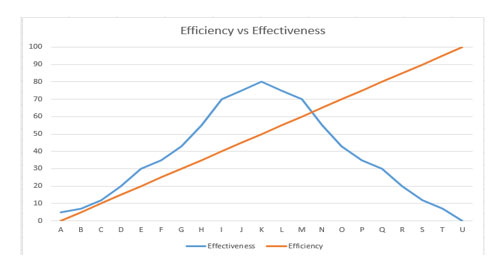

It seems as if the idea that “if a little is good, then a lot must be better” is being applied to the concept of operating a fire department like a business, however. This seems to be impeding the fire department’s ability to continue operating as a higher reliability organization. There is a diminishing return on efficiency when compared to effectiveness. An incredibly wasteful department is still at least minimally effective: Firefighters are responding to calls and taking care of the problem, but it is costing the community more than it should. As efficiencies cut waste, effectiveness is not affected at first. However, striving for efficiencies in the wrong place or based on the wrong data will affect the department’s ability to be effective. The opposite of being wasteful is being too efficient. It is important to use the proper data in the proper way when identifying areas to improve.

Figure 2. A contrived example comparing the effect of efficiency on effectiveness.

This is because numbers would make a perfect witness on the stand–they only answer the question that has been asked; nothing more and nothing less. It is likely that searching a fire department’s activated fire alarm data will reveal that 99 percent of the activated fire alarms are false alarms. This indicates that there is a 1 percent error rate in reporting, because 100 percent of activated fire alarms (using NFIRS data as the basis) should be false alarms if crews complete the reports properly. This is because we teach our officers to write the report based on what was found on the scene. Those activated fire alarms that were cooking fires, structure fires, or smoke removal calls should all be coded as cooking fires, structure fires, or smoke removal calls even if the call was initiated by an activated fire alarm.

RELATED: Fighting Fires with Data | Data Analytics in the Fire Service | Big Data Driving Operational Performance and Fireground Safety

Furthermore, checking the actions taken at an activated alarm helps develop a better picture. If the actions taken indicate some type of ventilation, then the activated alarm call was at the very least a smoke removal call and may have been a cooking fire coded as an activated alarm because there are fewer tabs to complete than if it is coded as a fire. For example, checking actions taken may reveal that ventilation is performed 10 percent of the time at an activated fire alarm.

Yet many fire departments are sending a very limited response to an activated fire alarm because they have found that 90-some percent of activated fire alarms in their department are “false alarms.” Fire departments do this based on a combination of data and the business principle of making the department more efficient because it increases the availability of apparatus for other emergencies; reduces apparatus hours; and reduces the exposure to apparatus accidents and firefighter injuries. However, it fails to take into consideration outcomes.

Defining a false alarm, in this example, is important. As discussed above, is an activated fire alarm really a false alarm if responding crews perform positive pressure ventilation to remove smoke from food that burned? It is true that the fire may have been confined to the container in which it was being cooked, but why did it not escape? Was it confined to the container because an adequate number of people responded in a timely manner to an activated fire alarm and found the problem before it became a kitchen fire? Is this, then, a “false alarm” just because it was not coded by the NFIRS codes for a fire or smoke removal?

This is an example of where data combined with an overpowering drive to operate efficiently instead of effectively has changed the fire service’s culture. Another way to look at the same example with data is that crews performed some type of ventilation at an activated fire alarm 10 percent of the time. This means that 10 percent of the activated fire alarm calls were within seconds or minutes of being coded as a cooking or building fire. Based on many department’s reduced responses to activated fire alarms, there is no resiliency–no ability to adapt adequately–for those activated fire alarms that turn into working fires . This means that the fire department is less effective because the outcome in the public’s perception is increased exposure to injury and property loss. A lack of resiliency–an inability to adapt to changing conditions–means that fire departments are becoming less of a higher reliability organization as we forget the lessons our predecessors learned and tried to teach us.

Most of all, it means that a fire chief somewhere may need to explain some day to a family that they lost their home because he or she chose to make the department more efficient in exchange for being effective. Instead of being able to say, “We did everything we could,” the chief will need to say, “Our data tells us that only 1 percent of our activated fire alarms are real fires, so we were willing to accept the risk that a family would lose their home since it happens so infrequently because we wanted to be efficient. Unfortunately, today, you are the 1 percent.” In business speak, the chief is saying that we reduced our outputs to reduce the need for inputs while accepting a certain percentage of negative outcomes for a small part of our population. We chose efficiency over effectiveness.

<< PAGE 1 | PAGE 3 >>

Craig Nelson works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.