BY TOM SITZ

The traditional 2-to-1 hauling system for moving a heavy object along a horizontal plane has been around a long time. It has also been a rapid intervention crew (RIC) tool for a while. I first learned it about 20 years ago in RIC training. The traditional method of deploying the 2-to-1 to assist in removal used two RIC teams, one inside and one outside (the haul team). In the traditional setting, the anchor point and haul team occupy the same general space outside the building. Usually, the haul team stands next to the anchor point.

Photos by author.

Using this method has a couple of drawbacks that are easy to overcome when using the improvised method.

- Using the traditional method, you need an outside team, which means extra personnel. In a staff-rich environment, it is not an issue. However, when you must prioritize critical tasks because the incident has now outresourced you, this could be a really big deal (photo 1).

- You have to coordinate the teams. The outside team does not have a visual on the down firefighter, and it is unrestricted from a movement and space standpoint. It can simply grip the haul line and walk or run in its direction of travel. This causes an issue for the inside team, which will not be able to keep up with the movement of the down firefighter without inside and outside coordination. You can move that down firefighter a lot faster than you can crawl in a smoke-filled environment; this can cause a separation between the rescuers and the down firefighter. If the RIC is using the down firefighter and the haul system as its reference for egress, once the separation happens, it is effectively lost. All the rope used in the system is moving with the down firefighter. Nothing is left behind for the RIC to find and reorient itself.

- Even though the outside team cannot see the victim, it needs a line of sight. This system cannot be used to pull the down firefighter around corners. Should the down firefighter get caught on something, the inside team must free him. If the haul team is not coordinating its effort and just removing the down firefighter as fast as possible because it has no restrictions, it can inadvertently ram him into a doorway at a pretty high rate of speed and apply a significant amount of force when trying to free him.

- You need the basic equipment: a rope bag, carabiners, and a pulley. A change-of-direction pulley and a 200-foot rope bag might not be available on everyone’s fireground (photo 2).

- The pulley is deployed from the anchor point, meaning in most instances that the down firefighter has already been located. I doubt the initial RIC is crawling around dragging a pulley system and rope while looking for someone.

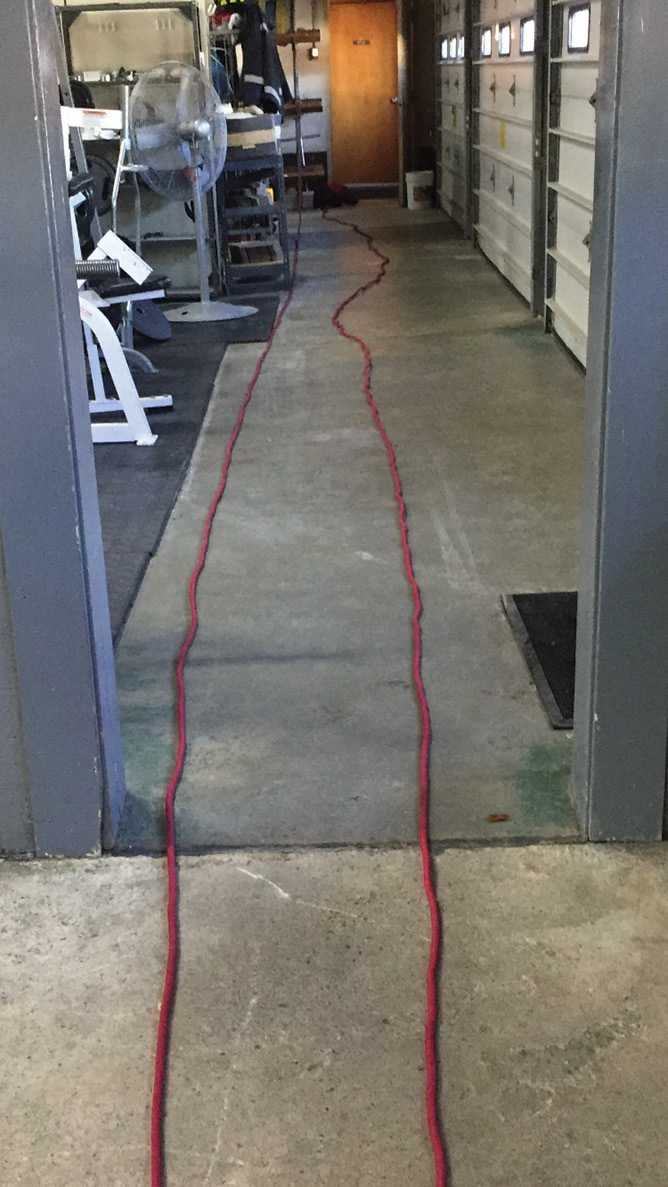

- Using this setup, your maximum length of deployment will be only 50 percent of your total rope. If you have a 200-foot rope bag, the maximum distance you can extend inside the building is 100 feet (photo 3).

During a recent RIC drill, we discussed and reviewed the traditional setup of a 2-to-1 system for removing a member who is significantly heavier than the RIC firefighters. We also discussed how someone who is easy to move on the training ground might become almost impossible to move on the fireground because of several varying factors over which we have no control. In our drills, we can control whether we use full personal protective equipment (PPE). We can control our ability to see. We can control the timing of the training. If we are honest, we don’t do physically taxing, intensive drills requiring cleanup on days that are really busy with runs. On days where we might be a couple of emergency medical services (EMS) reports behind, I come up with another drill topic requiring minimal setup and cleanup, and the drill time can be pushed back until we catch up on reports. Some things that we cannot control on the fireground will affect our ability to do something that we can do easily in drill but that we may struggle with or fail to accomplish on the fireground.

- The environment. Heat is not our friend when we are working hard, and noise increases stress. For example, the fire alarm going off makes verbal communication extremely difficult.

- Stress. Mental and physical stress can make the possible impossible.

- Fatigue. Have we been up all night, did we get a chance to eat, or are we already fatigued because we responded from another working incident?

Based on the above considerations, we brainstormed to see if we could develop an improvised system based on the tools that we would most likely have with us at the time. We worked two basic scenarios and developed improvised 2-to-1 systems for both scenarios.

Advantages of the Improvised 2-to-1 System

- Less staffing is required: no outside team is needed.

- A fixed anchor point is not needed. Your anchor is mobile and moves as needed with the system.

- The equipment is readily available and can be made out of the gear most of us carry.

- There is less mechanical advantage. We lose some advantage compared to the traditional system when we improvise the pulley. But it is still more than just trying to drag a victim without any type of mechanical advantage.

- The equipment needed has multiple uses. A pulley is pretty much just a pulley. But, the prusik cord carried has numerous uses in addition to simulating a drag rescue device (DRD). It can be used in conjunction with a six-foot hook as a step to get you over a wall or window.

Scenario 1: Level I search in a commercial occupancy. In my system, we have different rope search bags for a Level I and a Level II search. The Level I bag is 150 feet of rope in a bag that you carry over your shoulder. One end of the rope has a figure eight and a carabiner; this end is attached to your point of entry. The other end is clipped to a hook inside the bag. As the officer moves forward, the rope plays out of the bag. The Level II bag contains 200 feet of rope with knots every 40 feet and two 20-foot tethers. In a Level I search, you’re tied into your point of entry and should use this level every time you’re operating without a hoseline in any structure bigger than a house (photo 4). Our Level I search bag now contains the following equipment after working these scenarios: two locking carabiners, one prusik cord, and one four-foot piece of webbing with a water knot (photo 5).

- The entry team has anchored off at its point of entry and is advancing throughout the building when it encounters a down firefighter or is directed into the area because of a Mayday. This technique also works if a RIC anchors off at its point of entry as it searches for the down firefighter or deploys into a Mayday.

- Because of numerous factors, the entry team is struggling in removing the down firefighter. At this point, you can put in your improvised 2-to-1. You will use a carabiner in place of a pulley. If the down firefighter has a DRD in his gear, deploy it and tie the carabiner into it. This is your pulley. If the down firefighter does not have a DRD built into his gear, you now can apply either the prusik or webbing to act as the DRD. Put the prusik or webbing under and through both self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) shoulder straps and pull it through itself. Pull it tight to make sure you fed it through properly, and apply the carabiner (photo 6).

- The easiest way to apply the carabiner when you cannot see is to place the gate facing the ground and the head of the carabiner facing the down firefighter. Once you clip in, you rotate the head of the carabiner away from the down firefighter (toward you) and it ends up gate up for easy attachment of the haul line. This also keeps the carabiner in line, preventing gate loading (photo 7).

- Pull three or four feet of rope out of the bag and make a bight. Place the bight into the pulley. Your system is now in place (photo 8).

- Pull the haul line back toward your point of entry. Leave the rope bag and all extra rope inside the building. You control the speed of the extraction and the RIC is constantly monitoring the down firefighter.

Scenario 2: You stumble on a down firefighter or a civilian and have only the equipment you carry in your gear. Remember, you are deploying a hauling system for people who cannot be expediently dragged. You are using an improvised 2-to-1 system for anyone you have extreme difficulty moving. A situation where leaving someone in an immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) environment for an extended time could be the transitioning point from viable victim on the exterior to a nonviable victim because of the time in the IDLH environment.

- Your company takes out its personal rope bags. Hopefully, all firefighters are carrying at least 40 feet of personal rope. This rope is one of the most important items of personal safety equipment you can carry. (See “The Personal Rope: 40 Feet of Life Insurance,” Fire Engineering, April 2005.) Take off one of the carabiners to act as your pulley and connect two or three bags, carabiner to carabiner. In the high-angle rescue business, this would be severely frowned on and downright dangerous (some technical rescue readers may be freaking out right about now), but this is not a high-angle rescue; this is a rescue drag across the ground. There are lots of knots that would be appropriate for this evolution, but none of them are as easy as clipping two carabiners together. Remember, you cannot see and you are wearing structural gloves and are stressed. The higher your stress level, the more fine motor skills you lose.

- Clip the carabiner/improvised pulley into the DRD. If not available, use your rescue webbing as a girth hitch around the victim’s chest with the hitch part under the victim’s back (it ends up in the same position as the DRD). Then clip the carabiner into the webbing.

- In this scenario, you do not have an anchor point; everything is going to be improvised. Here, you can use a firefighter as the anchor point. The anchor firefighter now takes the rope and crawls in the direction of travel until he runs out of rope (he leaves three to four feet of rope at the carabiner to be used as the haul line). At this point, the anchor firefighter wraps the rope around his waist and sits down, planting his feet in front of him. Once he is anchored, the hauling firefighters grab the haul line and crawl to the anchor point. We know that there was a limit to what we could expect from an improvised firefighter anchor point. We wanted to simulate a victim who was twice as heavy as our anchor firefighter. We also wanted to run this drill on the slipperiest floor surface we had available (we wanted to try to simulate a tile floor in a commercial occupancy). So, we loaded 235 pounds of weight on the 185-pound dummy for a total weight of 415 pounds. The weight of the anchor firefighter was 190 pounds. This made the victim 225 pounds heavier than the improvised anchor (photo 9). The floor surface we used was a smooth coated concrete slab; we felt that represented the floor simulation. It certainly was not as slick as tile, but we felt it was close. The haul firefighter executed the drag without any noticeable differences or difficulties. The anchor firefighter would be slid forward a couple of inches during every drag but not enough to slow the removal or for the haul team to pick up the movements.

- We know that because we went carabiner to carabiner the connection will not pull through the pulley/carabiner. Since we know that the system is going to get locked up every 40 feet, you need a plan to overcome this. All you have to do is take the haul line out of the pulley/carabiner and move the connected carabiners past that point. This can happen quickly, and you reset the system for another 40 feet of pull.

Skills Incorporated into the Drill

- Declaring a Mayday. Declare a Mayday using a portable radio when the victim is found if simulating a down firefighter or declare an Urgent if simulating a civilian. If your radio system uses a repeater to talk to Dispatch or even radio-to-radio, have the RIC talk on a channel that will make them go through the repeater system. This is the most realistic training for emergency radio traffic. Have another firefighter on the same channel act as the incident commander, and if the traffic is unreadable or they do not paint a good, clear picture of what is going on, make them repeat it. You can simulate declaring a Mayday in training. Just saying “I would declare a Mayday here” is about as effective as simulating stretching a line for a drill.

- Assessing a down firefighter. During your assessment, you determine that the down firefighter is out of air and you can immediately solve that issue by deploying your emergency buddy breathing system (EBBS) (photo 10).

- Deploying your EBBS to the down firefighter (photo 11). We incorporated this into the drill and originally had the firefighter who had his EBBS in use attempt to help with the haul. The problem is that this firefighter has to stay right next to the down firefighter, and that does not prove to be very effective in assisting with the haul. We solved this issue by having the EBBS firefighter stay married to the down firefighter at the waist. The EBBS firefighter tightens the waist belt of the down firefighter’s SCBA and uses that as a handle to pull forward as the haul firefighters are hauling. This proved to be much more effective than trying to assist with the haul line (photo 12).

Hopefully, you will never need these skills on your fireground, but you will have them in your toolbox. With a large skill set, you will be better able to improvise and adapt to the situation. You cannot improvise a 2-to-1 hauling system if you do not know how to set up a traditional 2-to-1 hauling system. The important thing about going to schools and reviewing new research is not that you have to agree with everything. It’s is the exposure. Understanding why something will not work in your system is just as important as understanding why something will work. Think of how much problem-solving time is saved when you know what not to try. Lots of things were discovered or invented completely by accident in the American fire service.

TOM SITZ is a lieutenant and a 33-year veteran of the Painesville Township (OH) Fire Department. He has been a company officer for the past 21 years and has presented numerous times at FDIC International. Sitz is also an instructor for Lakeland Community College in the fire science program and has been a fire academy instructor since 1993.