Being a firefighter today is much, much more than simply fighting fires. The duties of a firefighter have changed significantly. The responsibilities have multiplied, and so has the danger-in more ways than the average citizen may ever imagine.

After successive, notable mass shootings, active shooters on high school and college campuses, and the rampages by psychotic individuals in the malls and streets of America, scenes of violence are increasing in frequency and magnitude. Horrific scenes of violence chronicled on the front page of the newspaper evoke fear in all of us. Television media play looped footage, visually imprinting the chaos into our subconscious while the ticker on the bottom of the screen keeps us updated to the minute. Nationally, the President of the United States has noted that these types of incidents have become commonplace in our society and that they need to stop.

As firefighters, one of our duties includes dealing with the emergent aftermath of these heinous acts of violence against humanity. Not all acts of violence are immense. Every day in the United States, there are “minor” violent crime assaults on citizens. The unreported events are often not deemed newsworthy by the media.

|

| (1-3) Photos by author. |

Moreover, first responders, such as firefighters, law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS) personnel, and hospital emergency room staff bear the brunt of a hostile patient every shift. From violent acts of physical confrontation and aggression to verbal threats of great bodily harm or dismemberment, the 911 responders of today face a much greater potential for injury because of seemingly unbelievable acts by the people receiving emergency help.

Law enforcement is known to have inherent dangers in dealing with the public. But, does a “normal, hard-working, U.S. tax-paying citizen who contributes to society” think that firefighters would be routinely verbally harassed, spit on, threatened, or even attacked in the course of their daily duties? An incident may result in physical harm to a firefighter, causing the “patient” to be charged with a felony. It may even cause a firefighter to be medically retired as a result of the injuries sustained. Some firefighters are killed by the needless violence.

In 2013, the late Fire Chief Glenn Gaines of Fairfax County, Virginia, cited the following from the 2004 Rand Institute study “Violence Against Firefighters”: “Approximately 88,000 firefighters are injured due to violence against them each year; about 2,000 of their injuries are potentially life-threatening” and that “The Bureau of Labor reports that public sector employees are four times more likely to experience assaults than private sector employees.”1

Increase in Violent Incidents

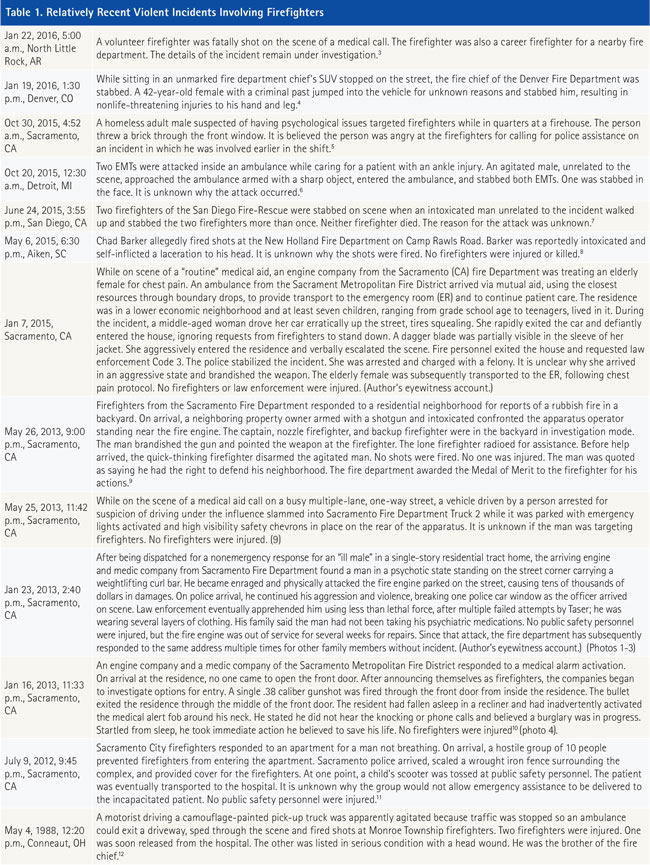

Table 1 contains a brief list of violent incidents toward first responders that may not have made the national news. Some are gleaned from the headlines of local newspapers. Some are examples provided by firefighters who verified them through personal interviews by first-hand personnel on scene. Each story illustrates a version of a hostile, unprovoked act encountered toward a firefighter or fire company. These incidents are from 2012 through 2016, with the exception of one, which was reported in 1988 when technology and sharing of information was not as advanced as it is today. The media reported firefighters being shot on the scene of a medical aid. Violent scenes directed toward firefighters today simply occur much more frequently than we care to admit.

Additionally, there have been significant incidents covered by the national news outlets that did make the evening television news. As a nation, we mourned for Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and New York City (9/11). Major acts of violence, terrorism, and racial conflicts have been well-documented.

Common Risk Factors

Violent incidents appear in various forms and circumstances. Often, first responders have misleading information based on the belief that 911 would be used only to summon help in a real emergency. Two recent incidents that made national news illustrate how scenes can be violent and potentially life-ending for the first responder.

It is a given that fire and EMS units will stage until law enforcement clears the scene if the incident is reported as a violent or potentially violent scene. “When there is a potential for violence, firefighters will normally wait for police to arrive, but there was ‘no indication this call was anything other than a typical medical emergency,’ said Gwinnett County (GA) Fire Captain Tommy Rutledge.”2 A lack of accurate information can have devastating effects on responders.

The objective of the following two incidents was to intentionally hold hostage or kill firefighters and law enforcement and EMS personnel.

- April 10, 2013, 5:00 p.m., Suwanee, Georgia. Five firefighters responded to what they believed was another routine medical call for chest pain. On arrival at the suburban Atlanta residence, the “patient” was armed with a gun and held four firefighters hostage. The fifth firefighter was released to move a fire apparatus away from the residence. Law enforcement responded. After three hours of negotiations, SWAT stormed the residence and killed the man. The man held firefighters hostage because he was demanding to have his utilities restored. Another report states his home had been foreclosed on. One SWAT police officer was shot and transported with a nonlife-ending injury. Firefighters were emotionally affected without physical injury. (2)

- December 25, 2012 (Christmas Day), 5:49 p.m., Lake Ontario: Webster, New York. William Spengler, 62, ambushed and opened fire on firefighters responding to a house set on fire. On conclusion of the incident, two firefighters, ages 43 and 19, were shot and killed; two other firefighters were shot and hospitalized with nonlife-threatening injuries; and one police officer was shot and wounded when he drove to the scene. Spengler took his own life by a single gunshot wound to the head as law enforcement advanced. Additionally, human remains, believed to be those of the gunman’s sister, were later found on scene. In total, seven houses burned. Spengler had been convicted of manslaughter in 1981 in the death of his grandmother. Although he was a convicted felon, Spengler had armed himself with a .38 caliber revolver, a 12-guage shotgun, and a .223 caliber rifle.13

Why the Violence?

Why are firefighters being killed or needlessly injured? One explanation offered is that in our society “acting out towards others seems to be occurring more often, and, to some degree, is viewed as OK.” This is seen in the increase in acts of road rage, spousal abuse, workplace violence, and armed attacks against all sorts of innocent people. Some social experts see these interpersonal conflicts as a consequence of a lack of frequent interaction with others. (1)

Another reason may be how society views its firefighters. “With the advent of today’s 9-1-1 system, firefighters and EMTs are called by the public to provide assistance for a wide spectrum of customer needs. What was originally intended for life-threatening emergencies has undergone a paradigm shift into a catch-all, government-funded, home health care agency and troubleshooting service,” writes Chief (Ret.) Howard Munding in the Executive Fire Officer program assigned research project, Violence Against Firefighters: Angels of Mercy Under Attack.14 Munding cites from Emily Hough’s 1998 article in Fire International: “As a result of this paradigm shift, the public’s view of firefighters and EMTs is declining from that of a respected position and hero to one of just another public servant or symbol of authority.”15

As a firefighter for more than three decades and a martial arts instructor, Munding has taken a proactive approach to dealing with scene safety. He has been studying trends of scene violence over the past 20 years and has become a subject matter expert relative to violence geared toward the fire service. He has determined that drug use and economic pressures add to the tensions first responders are facing.16

In 2004, at the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation Life Safety Summit in Tampa, Florida, representatives of the major fire service constituencies adopted the 16 Firefighter Life Safety Initiatives, among them Firefighter Life Safety Initiative #12: “Violent Incident Response deemed national protocols for response to violent incidents should be developed and championed.”17

Maximize Your Department’s Preparedness

Information is key to response. Firefighters can stage and wait for law enforcement to clear the scene prior to arrival if it is known that the scene is violent. Valid, credible information is critical to making safe, effective, life-impacting decisions for firefighters as well as patients. Quality dispatchers play a major role in the safety of line personnel.

Often, scenes change from the time of dispatch to the time responders arrive on scene. Information may be incomplete. Language barriers may interfere with effective communication. Cell phone service may be poor, or the “incident” may be a trap.

On a hostile scene, when law enforcement does its job, it aids fire/EMS in doing their jobs. It is extremely difficult to make the decisions that must be made within seconds at a hostile scene and that can have a life-changing impact on a firefighter or a civilian. Life safety can inadvertently be comprised at a hostile scene by factors such as (1) rapidly dispatching fire companies with only limited known information and (2) a rapidly deteriorating scene occupied by hostile actors. We can reduce the risks by reviewing our policies and procedures from the perspective of personnel safety. Some of the questions we should ask during this evaluation include the following:

- Is rapid dispatching worth the extra seconds it would take to ensure that the scene is safe by asking a few more questions?

- Are our members trained in what to do if they encounter an agitated, intoxicated, or despondent patient?

- Do our members know how to de-escalate the incident with prudent, egoless decision making?

- Has our fire department trained in the past year with our local law enforcement agencies on “minor” violent scenes, not just large-scale training scenarios?

- In busy systems with frequent 911 abuses, do we get enough sleep on shift so that we can think clearly to appropriately handle escalating scenes and act professionally?

If incidents turn out bad, who is to blame? The late James O. Page, an EMS pioneer and noted leader in the field, posed a very good question in “Unfinished Business” in the December 2000 issue of Fire/Rescue magazine: “Should firefighters be disciplined if we don’t like the way they handle violent patients? It’s like telling firefighters to enter a burning building, but failing to provide them with the necessary equipment or training-then punishing them when we don’t like the way they perform.”18

In 2013, after the killing of two firefighters by ambush in upstate New York and the taking hostage of four firefighters in Georgia, Burton (SC) Fire District Chief Harry Rountree issued his firefighters custom body armor. At that time, part-time Beaufort County (SC) EMS paramedic and former SWAT team medic Daniel Byrne said, “Body armor is a symbol that times are changing.”19

|

| (4) Photo source: “Green Sheet,” Sacramento Metropolitan Fire District, 13-7411. |

To further study violence and its effects, The Ohio State University Criminal Justice Research Center is hosting and has initiated the collaborative research project the “Historical Violence Database.” It will contain information on violent crime, violent death, and collective violence. According to its Web site, “No single researcher or group of researchers can examine enough sources in enough jurisdictions to achieve the goal [of an Historical Violence Database].”20

As discussed, scenes of violence can have direct and indirect effects on responders. Whenever a patient is injured or killed, a first responder may be investigated and/or punished. It is a sad state when public servants are placed in a situation they did not create in an attempt to render aid to persons who may be altered by drugs or alcohol. They may have great bodily harm inflicted on them and then may be punished by the fire department because they were inadequately trained or the fire department was short staffed or underbudgeted. At a minimum, the mental fatigue and ensuing stress of the months or years to follow can be more damaging than any physical injury sustained.

The past decade has shown violence toward firefighters is becoming more frequent and much more sinister. More conversation is needed. More data are needed. More study is needed. Much, much more training in situational awareness is needed. If you were chief of your fire department, what would you do to ensure Everyone Goes Home?21

References

1. Gaines, Glenn (2013, Aug 12). “Violence against firefighters.” Retrieved from www.firegeezer.com.

2. Effron, Lauren. (2013, April 10). “Gunman Who Held Four Firefighters Hostage in Georgia is Dead.” Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/US/gunman-held-firefighters-hostage-georgia-dead/story?id=18927171.

3. Moritz, John (2016, Jan 22). “Homeowner charged in fatal shooting of firefighter during medical response.” Retrieved from www.arkansasonline.com/news/2016/jan/22/volunteer-firefighter-fatally-shot-pulaski-county/

4. Paul, Jesse (2016, Jan 19). “Denver fire chief stabbed near department headquarters.” Retrieved from www.denverpost.com/news/ci_29404538/denver-police-investigate-stabbing-at-fire-station-at

5. Fire Dispatch. (2015, Dec 8). Personal interview.

6. Allen, Robert and Stafford, Katrease (2015, Oct 21). “Duggan: ‘Hero’ EMT stabbed in face saving partner.” Retrieved from www.freep.com/story/news/local/Michigan/Detroit/2015/10/20/paramedics-stabbed-detroit/74257050/.

7. Adams, Andie, and Stickney, R. (2015, June 24). “2 San Diego Fire-Rescue Firefighters Stabbed On Duty.” Retrieved from www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/Firefighters-Get-Into-Altercation-During-Call-309660001.html.

8. Staff (2015, May 6). “Man arrested after firing shots in New Holland Fire Department parking lot.” Retrieved from http://www.wrdw.com/home/headlines/Shots-fired-near-New-Holland-Fire-Department-in-Aiken-County-302701161.html.

9. Locke, Cathy (2013, May 27). “Two arrested in separate incidents after tangling with firefighters.” Retrieved from http://blogs.sacbee.com/crime/archives/2013/05/two-arrested-in-separate-incidents-after-tangling-with-firefighters.html.

10. Green Sheet. (2013, Jan 16). Sacramento Metropolitan Fire District. CA SAC 13-7411.

11. Lindelof, Bill. (2012, July 9). “Sacramento Police aid firefighters allegedly thwarted by group.” Retrieved from http://blogs.sacbee.com/crime/archives/2012/07/sacramento-police-aid-firefighters-allegedly-thwarted-by-group.html.

12. “Firefighters Shot Holding Traffic to Aid Ambulance.” (1998, May 4). Retrieved from http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1998-05-04/news/9805040163_1_firefighters-tuttle-shot.

13. Mach, Andrew and White, Jason. (2012, Dec 25). “Human remains found at home of gunman who ambushed firefighters.” Retrieved from http://usnews.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/12/25/16125861-human-remains-found-at-home-of-gunman-who-ambushed-firefighters?lite=.

14. Munding, Howard. (2006). “Violence against firefighters: Angels of mercy under attack.” (Executive Fire Officer Program). Retrieved from https://www.usfa.fema.gov/pdf/efop/efo39115.pdf.

15. Hough, Emily and Louderback, Joseph. (1998). “Attacks on firefighters,” Fire International; 161 (February-March 1998), 14-16.

16. Holdsworth, Angie. (2012, Dec 26). “Valley firefighter says violence against first responders on the rise.” Retrieved from http://www.abc15.com/news/region-west-valley/peoria/valley-firefighter-says-violence-against-first-responders-on-the-rise.

17. Munding, Howard. (2010, April 20). Firefighter Life Safety Initiative #12: National protocols for response to violent incidents should be developed and championed. Retrieved from http://www.everyonegoeshome.com/16-initiatives/12-violent-incident-response/.

19. McNab, Matt. (2013, Sept 20). “Burton firefighters to wear custom-fitted body armor on all emergency calls.” Retrieved from http://www.islandpacket.com/news/local/community/beaufort-news/article33532026.html.

20. Roth, Randolph. (2008). Historical Violence Database: Ohio State University. Retrieved from https://cjrc.osu.edu/research/interdisciplinary/hvd.

21. Everyone Goes Home. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.everyonegoeshome.com.

AARON DEAN began his career as a volunteer firefighter in 1990 in rural Shasta County, California. He earned his paramedic license in 1994. In 2001, he was hired by the City of Sacramento (CA) Fire Department, where he serves as apparatus operator. He has an MS degree in emergency services administration from California State University, Long Beach, and teaches fire technology at the high school and junior college levels. He is a published author and a speaker.

Violent Scene Response for Fire and EMS Agencies

Humpday Hangout: Scenes of Violence

The Violent Confrontation

Fire Engineering Archives