BY DON DOYLE

The opening minutes of a long-term incident involving a marine vessel may be the most critical-and the most productive-of the event. As at almost any large-scale incident, fire service agencies conduct a size-up, establish command, and commit resources. Over the next several hours, they call for extra resources and make decisions that will affect the course of the incident. With a large-scale incident involving a marine vessel, however, fire personnel could be involved with people who would have to perform tasks and roles we never knew existed.

Below is my account of how the 12 fire agencies comprising the Fire Protection Agencies Advisory Council (F-PAAC), working under the umbrella of the Maritime Fire and Safety Association (MFSA), created a training program that has reduced costs and improved the quality of training for the firefighters, company officers, and chief officers along the Lower Columbia River from the Portland-Vancouver area to Astoria, Oregon. This multilayered training program allows for improvements and growth. In addition, it creates a response plan that emphasizes those opening minutes of a potentially long-term incident and controls the direction of the fire agency’s reaction until more help arrives from other F-PAAC agencies.

Training Program Background

Much has been written about the February 1982 MV Protector Alpha fire at a Kalama, Washington, grain terminal that left one United States Coast Guardsman dead, one firefighter injured, and the cargo ship itself a total constructive loss. That shipboard fire was the catalyst for the creation of the MFSA, F-PAAC, and a training program that has lasted for more than 30 years-one that has trained at numerous locations across the United States (the Washington State Fire Academy in North Bend; the Center for Marine Training at Texas A&M; and the Hampton Roads Marine Fire Fighting Symposium in Virginia).

Training Objectives and Creation Training Objectives and Creation

When F-PAAC was forced to create its own training program for large-scale maritime incidents, the first item was to determine its objectives, outlined as follows:

Credibility is tough to establish and prove and is almost impossible to regain if you lose it-especially in the small world of the fire service, where everybody seems connected in a variety of ways. Like any government agency, we formed a subcommittee that answered to the F-PAAC Planning Committee. At first, it was simply called a “think tank,” where ideas flowed forth and discussions went on for hours. At the end of the process, we at least had a direction toward credibility, and it had the United States Coast Guard; National Fire Protection Association 1005, Standard for Professional Qualifications for Marine Fire Fighting for Land-Based Fire Fighters; and the Oregon Department of Public Safety Standards and Training Task Book at its center.

By embracing NFPA 1005 and dividing it into training modules and tasks, we discovered that we could create a multilayered plan, and each agency could pick whichever level or levels to which it wished to train its personnel. To move the process forward, we hired a training coordinator and the subcommittee “think tank” morphed into the “design team.” This is where all the ideas had to be put into a plan and on paper. Three Training LevelsWe created a curriculum for each of the three training levels: Awareness, Operations, and Technician. Awareness. The marine firefighter awareness level prepares personnel to assist with firefighting operations but not to enter an immediately dangerous to life or health atmosphere, except for an obvious rescue. Essentially, awareness-level firefighters would support the operations and technician-level personnel. The computer-based awareness-level training curriculum can be completed in a couple of hours and is available to F-PAAC participating agencies on the MFSA Web site. Alternatively, an instructor may provide the training at the respective agency’s location.

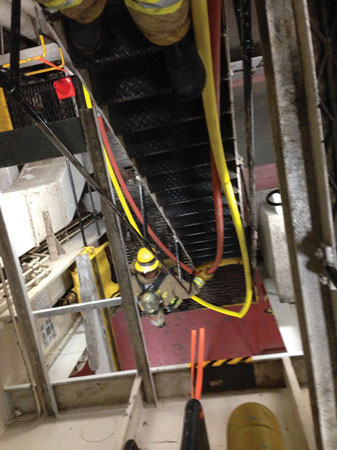

The awareness-level training focuses mostly on firefighter I and firefighter II activities, with the addition of recognizing safety issues and shipboard-specific tactics. Some of these specifics include meeting with vessel representatives; asking the appropriate questions; and accounting for crew members, contractors, and longshore and facility personnel who may be onboard. Since awareness-level personnel may be the first to arrive, they are trained to recognize the size and complexity of the incident and take actions that move the incident toward the desired outcome from the beginning. Operations. Operations-level personnel are trained to the most basic shipboard interior operations, which allows them to (1) perform safely and efficiently in a tactical role at a vessel incident, (2) recognize and report hazards through the chain of command, and (3) take appropriate actions when those hazards become life threatening. They are trained to read and interpret the vessel’s fire control and safety plan to others, including awareness-level personnel.

In addition, they must complete the eight-hour MFSA/F-PAAC operations-level classroom-based curriculum every three years, which can be done in-house or at an MFSA/F-PAAC-sponsored training event. Technician. Technician-level personnel are considered the leaders of operations- and awareness-level firefighters, directing actions as needed. They are familiar with vessel design and construction and their relation to fire suppression activities. Technician-level personnel are familiar with the best practices of incident strategies and can serve as advisers to the incident commander (IC) or to the general staff if the incident dictates. Technician-level personnel must complete the F-PAAC Technician-Level Task Book and become familiar with all MFSA-owned equipment and their locations and must be able to operate and perform basic maintenance on the equipment assigned to their agency. The technician-level training curriculum consists of four eight-hour hands-on training modules, in which each participant must prove proficiency to be considered qualified. Command. The IC is the key to the plan’s success. Consequently, the IC must understand all training levels and how to use each level in mitigating the large-scale incident. It does no good to have technician-level firefighters doing tasks that awareness-level personnel can do or to assign awareness-level firefighters tasks outside of their skill set. The marine firefighter IC is familiar with the best practices of incident management for mitigating maritime incidents. By recognizing present and potential hazards and incident requirements, the IC can support the mitigating strategies by assigning tasks appropriately, delegating responsibilities based on the incident size and complexity, and calling for the support based on incident requirements. Response Plan and Operations GuideUsing the new, layered training levels, we were then able to create a response plan that, using a theoretical response time, would allow the response of appropriately trained personnel to any Lower Columbia River port facility within that time frame. The difficult part was creating an operations guide that was appropriate for all F-PAAC agencies. For instance, what worked for the Portland- and Vancouver-area ports did not work for the Port of Astoria, and what worked for Astoria did not work for Longview, and so forth. Every agency with a port facility has its own strategic needs and available resources. All this had to be considered for the operations guide to succeed. The result was an operations guide that can be customized to fit each agency’s need and still meet the requirements of the F-PAAC organization as a whole.

When the poor economy reduced training budgets, potentially devastating consequences instead became a catalyst for us to reinvent how we train our personnel, the way we do business, and how we respond to vessel incidents. As the economy on the Lower Columbia River continues to improve significantly, the MFSA and F-PAAC are now poised to enter mutually beneficial partnerships with port facilities and private industries. These partnerships will sustain our presence as shipboard firefighters and a training program that is capable of growth and continuous improvement. For more information on the MFSA and F-PAAC, visit www.mfsa.com. DON DOYLE is a lieutenant with the Longview (WA) Fire Department. Involved with the Fire Protection Agencies Advisory Council (F-PAAC) and Maritime Fire and Safety Association (MFSA) since 1998, he has served for the past three years as the F-PAAC’S training coordinator. SHIPBOARD FIREFIGHTING:THE BASICS More Fire Engineering Issue Articles Fire Engineering Archives

Must View

Elevator Rescue: Rope Gripper EntrapmentMike Dragonetti discusses operating safely while around a Rope Gripper and two methods of mitigating an entrapment situation.

Two Workers Killed, Another Injured in Explosion at Atlanta Delta Air Lines FacilityTwo workers were killed and another seriously injured in an explosion Tuesday at a Delta Air Lines maintenance facility near the Atlanta airport.

|