By Eric G. Bachman

There are many terms and acronyms that represent the operational tendencies of an organization such as standard operating procedures (SOPs), standard operating guidelines (SOGs), standard operating outlines (SOOs), general operating guidelines (GOGs), general operating outlines (GOOs), and so on. There is debate over terminology where the suffix descriptor of procedure vs. guideline opens up the fire department to more liability than the other. In the grand scheme of things, it really doesn’t matter what they are called, especially if things go wrong. If you have one or the other and you don’t follow it, or you don’t have either, your department opens itself up to increased liability. Their content, implementation, and adherence are the important factors. Regardless of your terminology opinion, the fire department should have written statements on how things are to be done throughout the organization. Not only should they be in place, but they should be followed as well.

For the purpose of this article, the reference to SOPs is all-inclusive with the terms above. Some organizations and personnel within an organization do not fully embrace the practice or necessity of SOPs. A common response is that every incident is different; therefore, it is impossible to have a SOP for every scenario. Although no two incidents are the same, there are common tasks, considerations, and precautions universally applicable no matter the situations.

SOPs are a fundamental and essential part of fire department administration and operations. Some departments have comprehensive volumes while others have vague procedures or guides. And still many today do not have any whatsoever. If SOPs are not in place, no one knows the score, and no one will be on the same sheet of music.

PURPOSE

The purpose of SOPs is wide ranging; they help to identify the goals of the fire department, set the expectations of its personnel, and provide administrative and operational benchmarks. They define how operations are to be conducted, establish job performance requirements, and integrate full-circle the operations of the organization. They also yield unbiased consistency, indiscriminate of department personnel. SOPs may also account for certain administrative and legal requirements. If the organization does not have SOPs, incidents will likely be a “free-for-all” with no command, control, or concentration on safety. The end result is usually unfavorable.

CATEGORIES

The topics that SOPs address can be exhaustive. Their development is more of an art than a science because of the diversity in fire department dispositions. As a starting point, there are several categories of procedures common to most organizations. One is Administrative, which can include the organization’s mission statement, a definition of its chain of command, and descriptions of position titles and their respective roles and responsibilities. Other elements that are commonly under administrative procedures include application or hiring processes, uniforms classes, exposure control, documentation, and incident reporting. Administration may also include policies and procedures for antiharassment, defining drug and alcohol policy, describing personnel violations and discipline practices, addressing tobacco use, and physical requirements. A second SOP category, Prevention, outlines the public education practices of the organization as well as other outreach efforts.

Training is another category vital for establishment of performance levels, qualifications, or prerequisites for daily organization functions and incident operations positions. Often, the training section addresses basic training requirements as well as position specific criteria. This category may endorse pro board certifications, state and local delivery programs, refresher requirements (photo 1), and certain equivalency curriculums.

(1) Training SOPs often prescribe annual hazardous materials refresher training such as decon.

Another common category is Emergency Operations. This can be quite lengthy and comprehensive depending on the capabilities of the organization and the potential hazards within the district. Common procedures within this aspect include incident command, safety and risk management, accountability (photo 2), staffing requirements, apparatus response order, postincident operations and critiques, and responder rehabilitation, among others.

(2) Accountability systems are important for firefighter safety.

There also may be a Special Operations section that outlines and prescribes fire suppression actions (photos 3 and 4), emergency medical service operations, rapid intervention, Mayday procedures, hazardous materials response, and technical rescue events. Also included may be disaster operations for large scale man-made or natural events. The specificity of this is limited only to the potential events an organization can face.

(3, 4) SOPs include fire suppression activities.

Fire administrators must remember that SOPs are living documents. They are not “one and done” documents to be shelved and looked at only when something goes wrong. They must be consistently reviewed for relevancy. They must be compared to the applicability of hazards, and they must be updated to reflect administrative, organizational, and technical changes in and out of the organization. SOP maintenance is key; it is a never-ending aspect of fire service preincident training, preparedness, and operations.

GETTING STARTED

Organizations without SOPs may be overwhelmed. After all, there are not many specific training programs on SOP development and maintenance. However, today’s SOP development is easier. Online searches will yield many examples that can be refined to local needs. Other references such as www.firefighterclosecalls.com provide valuable tools and examples of SOP development.

Some fire departments provide their SOPs online. A good example of a well-structured SOP can be found HERE. It is not necessary to reinvent the wheel when so many resources are available. And, in most cases, other fire departments would be cooperative in sharing their SOP information with other organizations.

Internet sources are there to help. Departments borrow SOP verbiage from one another all of the time. Each will tweak borrowed information to the disposition of the organization. Topic specific searches such as rapid Intervention and Mayday operations will yield numerous examples of varying specificity. The art of SOPs is the reflection they have on the organization they represent. To say one SOP is wrong is not appropriate; the SOP may just be vague or incomplete. But if it meets the needs of the respective organization, if it is endorsed and enforced, and if personnel are trained to the expected performance, it is not wrong. Some SOPs may be subjective, but personnel have to be objective and open to the goal, intent and expected performance criteria of each.

The excuse of not knowing what to include in SOPs is a mute point. If you don’t have Internet service, contact the Learning Resource Center at the National Fire Academy and request an authorization to research. Have them send you information on a particular topic free of charge. There really is no excuse to not investigate these vital rules except resistance to change and bullheadedness. Those two characteristics, however, will get you or your personnel killed.

Do not develop SOPs just for the sake of having them; they must be relevant to your district’s disposition. A SOP on high-rise firefighting operations is useless to a fire department that does not protect high-rises. The Federal Emergency Management Agency and United State Fire Administration offer a free resource entitled “Developing Effective Standard Operating Procedures For Fire and EMS Departments” (Pamphlet FA-197). It is available online at http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa-197-508.pdf . It outlines the roles and functions of SOPs as well as how to conduct a needs assessment. This is a great resource that further describes how to develop, implement, evaluate, and maintain SOPs.

AFTER ACTION REPORTS

Fire departments, peer groups, and independent agencies often perform after action review/reports (AARs) on large or extraordinary circumstance incidents. These reports typically review what happened, outline the chain of events, and lists measures to prevent future adverse affects. AARs and other incident assessments identify contributing factors as well as actions or inactions that facilitated the incident outcome. They too, offer suggestions or recommendations for organizational improvements. Personnel throughout the fire service must study, analyze, and compare published reports to their local conditions. Similar circumstances should be cause for review of the recommendations. Embrace and apply applicable recommendations. Just because your fire department has not sustained a serious adverse event at a facility similar to a venue in an AAR from the other side of the country does not mean it won’t happen to you.

When reviewing AARs, there are many common recurring issues such as a lack of training or structured incident command system (ICS) or no assembled rapid intervention capability. Another common issue is a lack of SOPs, which run the gambit from accountability procedures to fire suppression actions to safety practices.

The National Institute for Occupational safety and Health’s (NIOSH’s) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program (FFFIPP) is a great resource to learn why certain incidents ended tragically and what can be done to prevent similar occurrences. The site is located at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire. These reports provide an overview of certain incidents and provide preincident backgrounds of the venue, victims, and the organization. Often, the reports provide incident timelines to show how quickly things deteriorated. A goal is to identify issues and recommendations applicable to all jurisdictions as a training and prevention tool.

An issue that frequently arises in the FFFIPP reports yet is infrequently a part of most fire department SOP libraries regards preplanning (or the lack thereof). On July 3, 2012, a firefighter died searching for a fire in a large egg processing plant. His crew worked to breach a wall to access the seat of the fire because the access was blocked by wooden pallet stacks. The victim became disoriented and ran out of air, and rapidly deteriorating and extreme fire conditions prevented his rescue. He was removed from the building the next morning. The report identified numerous contributing factors including lack of scene management, no rapid intervention team (RIT) established and ineffective tactics. One of the key recommendations was to “conduct pre-incident planning inspections of buildings to facilitate development of safe fire-ground strategies and tactics.”1

On July 13, 2010, seven firefighters were injured at a metal recycling center fire. The 45,000-square-foot building housed several businesses. Portions of the building were constructed ordinary and heavy timber. A 60- x 100-foot section of the building was under a bowstring roof truss assembly. Nearly 40 minutes into the incident, an explosion threw debris, burning embers, and shrapnel throughout the area. Fire apparatus was damaged, and seven firefighters were injured. Factors contributing to the outcome included lack of an incident safety officer and the unknown and unrecognized contents. The NIOSH report provided several recommendations including to “ensure that pre-incident plans are updated and available for responding fire crews.”2

On June 15, 2011, a firefighter was killed by a roof collapse at a church fire. Initially, crews were met by light smoke and no visible fire. Unknowingly, the attic space was well involved. When crews opened the ceiling, conditions changed rapidly, and they were immediately instructed to evacuate. At the same time, the roof collapsed, trapping the firefighter. Extreme fire and collapse conditions prohibited his rescue. The NIOSH report noted that the fire department had numerous and wide-ranging SOPs covering topics such as incident management, dress code, and public relations. The report identified numerous contributing factors including lack of water supply, the construction type, and ineffective strategies. One of the recommendations is that the “fire department should conduct pre-incident planning inspections of buildings within their jurisdictions to facilitate development of safe fire-ground strategies and tactics.”3

A SYSTEMS APPROACH

Having a preplan, prefire survey, or preincident intelligence SOP is not the silver bullet to preventing firefighter injuries and line of duty deaths. However, when developed, initiated, enforced, and practiced, it is part of the service cog that will complement other SOPs and contribute to better informed strategy and tactics. It will improve personnel safety and foster development of countermeasures for site-specific challenges prior to an incident.

SOPs are not preplans or precise response steps taken for each facility. However, as with any fire department task, there must be guidance or steps to follow to initiate preplanning, prefire surveys, or preincident intelligence, or any other term or practice that meets the department’s preparedness goals. When reviewing textbooks, articles, and reports, the assertion to the importance of preplanning is stressed.

One cannot effectively develop a facility preplan or safely engage in preplanning activities without guidance or training. There are general steps and considerations to this in the same way where one cannot effectively engage in fire suppression without guidance and training. The haphazard reference to preplanning has extreme examples, from those that regard a facility tour as preplanning to those that aggressively study and collect facility data to determine fire department limitations and countermeasures.

NATIONAL FIRE PROTECTION ASSOCIATION (NFPA) 1620

When a fire department says they preplan, I ask to review their preplan SOP (which leads to me getting a “dear in the headlights” look). Have a preplan SOP in place to guide the process, prescribe the collected data criteria, illustrate the methodology for information storage and maintenance, and address other specific local elements. A good preplanning resource is NFPA 1620, Standard for Preincident Planning. It outlines a preplanning process as well as considerations for collecting physical and site characteristics including protection mediums and storage conditions. It also includes several appendices that provide case studies, common site characteristics, and examples of data forms and map formats.

The importance and reliance on preplanning has never stressed more. NFPA 1620, 2010 edition, was retitled to Standard for Pre-Incident Planning from its previous versions that were prefaced as a recommended practice; not a standard.

PREPLAN SOP CONSIDERATIONS

One of the first steps in developing a preplanning SOP is defining its purpose, which could be to describe the process of conducting preincident surveys as well as prescribe the desired data to be obtained. Its purpose could also include information storage, management, and dissemination practices. Preplanning essentially establishes a baseline of information applicable to all protected elements. Some venues may present extraordinary circumstances and challenges that will require efforts beyond the minimum criteria established in the SOP (photo 5).

(5) Specialty facilities can present unique challenges.

Consider identifying the program’s goals. This establishes the scope and focus of the SOP and its relevance to the department. Examples of program goals include identifying venue-specific information for use in pre- and post-dispatch operations and exercises. Another may be to identify operational, public, and responder life safety challenges for contingency development. And, very importantly, it may compare current response capabilities against the protected elements to identify deficiencies in policy, procedures, staffing, equipment, and training.

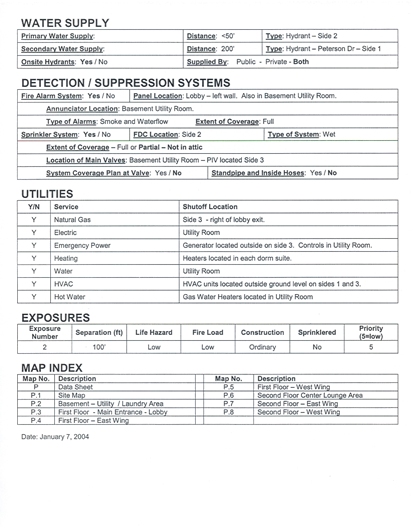

In some NIOSH reports, preplanning recommendations are specific to certain occupancy types such as mercantile and business establishments. Although a preplan SOP should establish the scope of facilities, it should not exclude any facility. It may not be feasible to preplan single-family dwellings, but the SOP could provide outreach protocols to identify special circumstances such as group homes, in-home day cares, and residents with functional- or access-dependent impairments. A preplanning SOP should include minimum information criteria (photo 6) and should prescribe use of organized data forms (photos 7, 8) rather than a haphazard collection using a blank notepad. The SOP should also outline the survey process including contact and subsequent appointments with facility personnel.

(6) Preplan SOPs should establish elements to be identified such as fire protection systems.

(7, 8) Data forms help organize facility information.

Additionally, a preplan SOP should include the support equipment necessary to engage in a preplan tour. Also develop a prefire survey kit to include the typical elements such as collection forms, writing utensils, personal identification, flashlights, a tape measure, measuring wheel, a camera, and so on (photo 9). The SOP should include procedures to follow when an unsafe facility practice is found. This is especially important for fire departments that do not have a code enforcement or inspections division.

(9) Maintain a kit with appropriate tools to conduct facility surveys.

Outline special considerations such as the permission to photograph facility elements to support preplanning and training. In some cases, facilities will prohibit photographing certain areas. Also consider, as part of the SOP, conducting after-hours windshield surveys to identify special conditions such as accessibility, security, and storage issues that may be employed when the facility is closed.

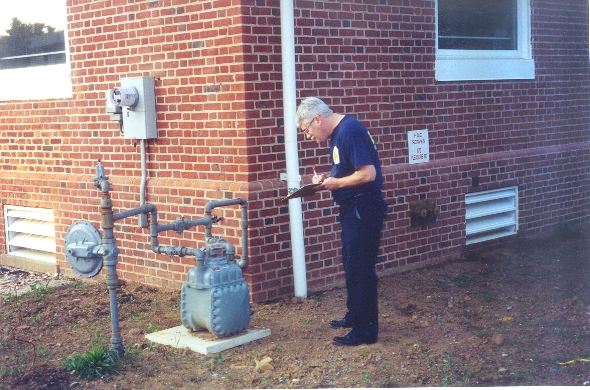

Also include code of conduct provisions. Fire department staff will be interacting with the public and facility personnel; the staff’s conduct should be punctual, courteous, and respectful to facility personnel and its operations. The SOP could also prescribe preplan survey attire worn. Whether career or volunteer, you are a representative of the fire department and should dress professionally to portray a respectful image (photo 10). What would you think if someone came to your establishment dressed in shorts, a ripped T-shirt, and flip-flops?

(10) A volunteer firefighter in uniform notes gas valve location during a preplan survey.

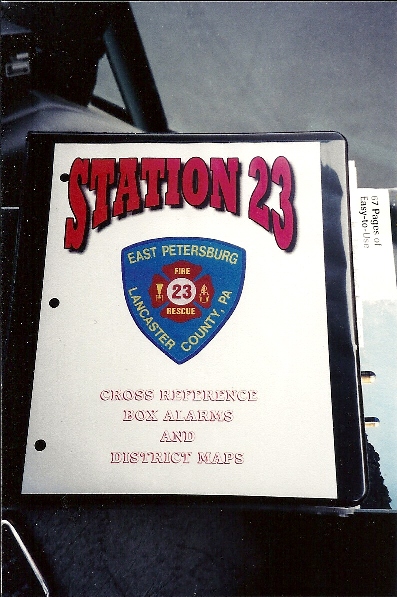

Next, the SOP should prescribe how to process information. Is the information placed in a filing cabinet or in a ring binder (photo 11) or is data entered into electronic mediums such as apparatus-borne laptop computers (photo 12)? The SOP should also include a system of checks and balances for accuracy of the information. Is there a review process before the data is considered vetted or approved for dissemination?

(11) Ring binder with district preplans.

(12) Laptop computers can store much site-specific information.

If maps are a part of the preplan, the SOP should provide for minimum map criteria (photo 13) such as directions; side references; access points; utility valves, meters, or control locations; and water sources. Another aspect that is often haphazard is symbols. The symbols used must be consistent when identifying systems and other infrastructure elements. A fire department should adopt and train personnel on specific map symbols.

(13) Preplan SOPs should include minimal map elements for consistency.

One of the last but most important preplan SOP considerations is management and maintenance of information. Once the information has been collected and placed in a ring binder or on a laptop, prescribe a training schedule and consistent review process with department personnel to ensure the accuracy of information.

A process such as preplanning is often perceived as simple. I have heard department leaders tell firefighters to “just go out and list what the facility has.” There is much, much more to it. It is a methodical process that requires guidance, establishment of expectations, and benchmarks similar to other fire service tasks.

There are many considerations and caveats that can influence the effectiveness of a preplan system and program as well as the organization’s overall goals. And, for other mission specific SOPs like RIT, accountability, and ICS, a preplanning SOP is just as important. The only wrong SOPs are the ones not written, enforced, or updated. Much time is spent in after action reviews reasoning as to why things went bad. Why not use that time on the front end of an incident to prevent bad things from occurring through writing, training, and reinforcing effective and relevant SOPs, preplanning included?

Photos by author.

REFERENCES

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “Volunteer Fire Captain Runs Low on Air, Becomes Disoriented, and Dies While Attempting to Exit a Large Commercial Structure.” Texas, Report #-F2010-16.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “Seven Career Firefighters Injured at a Metal Recycling Facility Fire.” California, Report #F2010-30.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “Career Fire Fighter Dies in Church Fire Following Roof Collapse.” Indiana, Report #F2011-14.

Eric G. Bachman, CFPS, is a 29-year fire service veteran and a former fire chief of the Eden Volunteer Fire/Rescue Department in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. He is the hazardous materials administrator for the County of Lancaster Emergency Management Agency and serves on the local emergency planning committee of Lancaster County. He is registered with the National Board on Fire Service Professional Qualifications as a fire officer IV, fire instructor III, hazardous materials technician, and hazardous materials incident commander. He has an associates degree in fire science and earned professional certification in emergency management through the state of Pennsylvania. He is also a volunteer firefighter with the West Hempfield (PA) Fire & Rescue Co.