BY JERRY KNAPP

House fires today are different than when our fathers were riding the back step. Yes, firefighters actually did ride the back step back then, when house fires were not a significant threat to their lives. Times have changed: Our fathers retired, and we don’t ride the back step anymore. House fires have changed as well. They are our most important alarm and more of a threat to firefighter safety than we realize. This article examines the strategic and tactical changes that may be necessary for safety and success at modern house fires.

Remember, there is no silver bullet in our profession that ensures a great outcome. The material presented here is for your consideration and possible fireground application. Apply it only after carefully sizing up and evaluating the fire scene and reviewing your experience so you can develop an appropriate search, rescue, and fire suppression plan for a modern house fire.

House fires include fires in private dwellings, wood-frame houses, duplexes, and double deckers; a house is where one or more people live. It is also where fire most often injures and kills civilians and firefighters.

According to the United States Fire Administration (USFA), on an average day in the United States, nine civilians perish in fires and 49 are injured, most of them in their own home. In a quick review of the Web site FirefighterCloseCalls.com, on just one day, the following house fire deaths and injuries were listed: A Rhode Island fire captain died of a heart attack at a house fire; in Tennessee, a firefighter’s hands were burned at a house fire; New Orleans (LA) firefighters were injured when a duplex collapsed on them; and a Columbus (OH) firefighter was injured when he fell in a two-story home.

GOPHER HOUSES: OLD HOUSE, NEW PROBLEMS

Because of the depressed economy and the increased cost of housing nationwide, some older homes have become overcrowded with an excessive number of occupants. Essentially, it’s an old home with new strategic and tactical problems. These “gopher homes” may be the next new and most deadly threat we face. This local headline, “28 people left out in cold at house fire,” involved an older Queen Anne home that had been transformed into apartments. Another headline, “13 people escape house fire,” discussed a fire in a small ranch home that was quite fully occupied.

Communities with seasonal, transient populations such as students, farm/industrial workers, vacationers, or sports fans, often have extreme problems with overcrowding in houses. For example, in college towns that have fraternity houses and other older homes in which students may occupy every room, a house fire can turn into a mass-casualty event.

|

| (1) In this private dwelling, firefighters discovered an apartment on the first floor, three single-room occupancies on the second floor, and an apartment in the attic. (Photo by Tom Bierds.) |

Gopher houses look like private dwellings from the outside but often conceal deadly surprises for firefighters. These modern house fires present three critical hazards to firefighters and may require changes to traditional private-dwelling strategy and tactics. Recall the vital importance of the 360° size-up, especially at these fires.

Hazard #1: locked doors on rooms converted to single-room occupancies (SROs). In a normal home, we can duck into a bedroom and close the door if things get nasty while searching the home or operating on the floors above or near the fire. But if the bedrooms are converted to SROs, more than likely, each room will have locks. Hence, firefighters may be trapped in hallways during a rapid fire development on the second or third floor. Sure, it is easy to say you can force your way into one of these rooms, but there will be near-zero visibility, intense fire and heat, and deteriorating conditions. The odds are not in your favor. If during your size-up or search operation you detect SRO conditions, notify command as soon as possible. Forcible entry and search and rescue operations will require much more personnel than a normal home would to maximize effectiveness and provide for safety of our members.

Hazard #2: illegal construction. Usually, these homes are illegal conversions of larger older private dwellings. Construction methods often completely disregard ingress, egress, and limiting fire spread, all of which affect firefighter safety. A common modification in dividing the home into upstairs and downstairs apartments is sealing off the interior stairwell. This prevents access for search teams and the hoselines from reaching a second-floor fire or attacking a first-floor fire to protect members operating above. The rear door and access to a stairwell may be the only way to the second floor. Depending on the layout for the house, this may be reversed; there may be no access to the second floor from the front of the house where you would expect to find the stairs behind or near the front door. So don’t be surprised if you can’t get there from here, and have a Plan B in place if staffing and equipment allow. Move your existing resources to Plan B quickly when necessary. Delays in getting water on the fire quickly by normally accessible interior routes can render conventional tactics and strategies ineffective, thus allowing the fire to grow quickly to life-threatening levels for civilians and firefighters.

|

| (2) Although designed to resemble an old farmhouse, this modern house incorporates many modern features and construction materials. Because of changes in occupancy, furnishings, and construction methods/materials, contemporary homes may contain many life-threatening firefighter hazards. Don’t underestimate them. (Photos by author unless otherwise noted.) |

Captain Bill Gustin of Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue suggests that in these cases, it is critical to get water on the fire even if you have to apply it from the outside through a window. In the past, this would have been an absolutely incorrect suppression method. However, because of today’s changes to the typical house, including bars on windows and locked doors for security combined with illegal modifications, darkening down the fire from the outside is a viable option if your engine company entry or your aggressive interior attack is delayed. In essence, it is the lesser of two evils: not applying water and allowing the fire to progress to flashover and killing anyone inside with even a chance of survival or applying water with a straight stream and creating some steam inside and likely decreasing visibility but controlling the fire.

|

| (3) This rollaway bed, found in a hallway, could become an entanglement hazard and, hence, a deathtrap for firefighters in a rapidly developing fire. Firefighters have been killed after they have been caught in bicycles, rollaway beds, and other hazards. |

Hazard #3: blocked exits. The Santa Ana (CA) Fire Department conducted full-scale burn tests several years ago to prove that houses that contain more people and their belongings burn faster than normally occupied and furnished homes. In short, they found flashover occurring two minutes faster in homes that are overoccupied and overfurnished with belongings. For firefighters, more stuff and more people living in small spaces often result in blocked exits as well. Additionally, storage space is limited, so we frequently find firefighter death traps like bicycles and toys in hallways and stairwells.

These occupancies may be difficult to detect since it is in the best interest of the occupants and owner (who is collecting a very nice rental income) to disguise them. Traditionally, we would look for signs that show multiple occupants (e.g., multiple mailboxes or gas/electric meters). But the best indicators of gopher houses may be the following:

- Extra trash containers. There are more than an average family would need or large amounts of trash outside.

- Extra cars and parking spaces. Often each occupant, especially if it is a private dwelling converted to a SRO, will have a car-again, more than you would expect to support a traditional family.

- Extra TV satellite dishes or cable TV wiring. Take a ride around your first-due area at night. Look for lights on in the attic and basement. Better yet, look for the blue flickering of televisions or computers indicating that these usually unoccupied spaces have been converted to living spaces and are occupied. Often, illegal immigrants, college students, or folks in poorer neighborhoods will pool their limited financial resources and live in very close quarters in what once was a single-family home.

MODERN HOUSE CONSTRUCTION

Modern house fires are significantly different from those the previous generation of firefighters faced because of changes in construction methods and materials. We are all too familiar with the hazards of truss, laminated beam, and wooden I-joist lightweight construction components and construction techniques. Yet we still read of firefighters being burned to death falling through floors and dying at the common house fire. “Through the door, through the floor” is a common battle cry, but this scenario continues to injure and kill us. It is easy to say that we need to change our strategy and tactics but, despite hard evidence, it seems often too hard for us to do.

![(4) Large, uninterrupted void spaces in modular homes can allow rapid fire spread, as in this fire. In just a few minutes, this occupied structure was fully involved; occupants narrowly escaped and were unharmed. [Photo courtesy of Acushnet (MA) Fire Department.]](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/knapp4-1304FE.jpg) |

| (4) Large, uninterrupted void spaces in modular homes can allow rapid fire spread, as in this fire. In just a few minutes, this occupied structure was fully involved; occupants narrowly escaped and were unharmed. [Photo courtesy of Acushnet (MA) Fire Department.] |

As reported in “Structural Collapse: The Hidden Dangers of Residential Fires” (Fire Engineering, October 2009), a live-burn study comparing structural integrity of legacy vs. wooden I-beam floor joists showed a legacy floor joist (2 × 10) had a collapse time of 18 minutes, 45 seconds when subjected to a laboratory-controlled fire load. The 12-inch wooden I-joist floor collapsed in 6 minutes, 3 seconds. Modern house fires perform differently under fire conditions. Our father’s firefighting tactics, timelines (“you have 20 minutes before you worry about collapse”), and strategies may no longer apply. At a minimum, we should compare our strategies and tactics against modern research, fire behavior, and experience.

For example, young or inexperienced firefighters can become overconfident thinking their high-tech thermal imaging camera (TIC) will keep them safe. However, the same study showed that the wooden I-beam floor system that burned at temperatures of nearly 1,300°F showed only 85°F at the top surface of the carpet. This is far too low for the TIC to provide even a clue of the danger below. Interestingly, the legacy joist burned producing a maximum temperature of 850°F with a carpet surface temperature of 73°F.

The key to safe operations at homes of dangerous construction is to identify the construction before the fire. During a Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) several years ago, I asked the late Frank Brannigan what we could do about the widespread use of trusses in homes. In his typically animated response, he said, “Jerry, for goodness sake, the building did not just land from Mars and catch fire! It has probably been there for years. Why should the fire department not be aware of it and know it has trusses?”

Modular construction. At a later FDIC, Chief Kevin Gallagher of Acushnet (MA) Fire Rescue gave a class on the dangers of prefabricated homes. Among the hazards cited for such structures was the use of adhesives to attach gypsum board to ceiling joists. Additionally, because the home is constructed in modules, like several boxes stacked on each other, a 20-inch-high uninterrupted horizontal void space can exist between the first-floor ceiling and the second-floor subfloor. When a simple, routine contents fire on the first floor causes the ceiling adhesive to fail and fire enters this void space, it can run the length and width of the house, spreading fire rapidly. This modern construction method can rapidly lead to a fully involved house fire. It’s another example of modern construction techniques creating a new and dynamic fire hazard for the common house fire. What was once a bread-and-butter, room-and-contents fire with little hazard in the modern house can be a fatal alarm for unsuspecting firefighters.

The West Haverstraw (NY) Fire Department responded to a modular home fire and found smoke issuing from everywhere but could not find the source. When interviewed, the occupant stated he had discharged a fire extinguisher into the downstairs bathroom floor air duct because smoke was coming out of it before he called the fire department. After some more searching, the truck company opened the ceiling in the nearby living room because members heard crackling sounds. The bathroom ceiling exhaust fan had shorted out and energized the wire coil of the plastic fan exhaust duct, which ran through the void/truss space between the first-floor ceiling and the second floor to the outside. The initially small exhaust duct fire had burned not only through the plastic exhaust duct but also into an eight-inch flexible plastic duct that supplied forced air from the heating system. When the house thermostat called for heat, the system fan activated, blowing air through the burned-through supply duct onto the the small fire in the void space, causing it to grow quickly. To compound the problem, the second-floor wood-truss framing supported a large water bed above. A delay of a few minutes on this alarm, and this fire may have been the subject of a multiple firefighter line-of-duty death report.

Energy-efficient windows. Energy-efficient windows (EEW) are another construction component that our fathers’ generation did not have to address. Tests conducted at the Rockland County (NY) Fire Training Center in Pomona revealed two important factors. First, the sash and frame material determines how the window may react to a fire load. In our live-burn tests, vinyl frames and sashes failed long before older, single-pane wooden sash and frames. This was confusing because all fire experience with EEW was to the contrary. After numerous discussions with experts and literature research, we determined that EEWs with more substantial sash and frame material (e.g., aluminum or solid wood) did resist heat failure longer than traditional single-pane wooden windows. Of course, this keeps the heat of the fire in longer, making conditions inside difficult while at the same time not showing any visible signs of fire on the exterior.

|

| (5) An energy-efficient window (EEW) test fire at the Rockland County (NY) Fire Training Center shows a vinyl sash EEW on the right melting just prior to most of its glass falling out. The single-pane wood-frame window at left retained its integrity much longer than the EEW. When large pieces of the window fell out, air rushed in, and the fire quickly reached flashover. |

We also noted that in some tests the interior pane of the EEW failed first, partially, or almost completely falling inward toward the fire with the associated sound of glass breaking. Firefighters could be fooled into thinking that ventilation has been accomplished when it had not. We called this a “false vent.”

Vinyl siding. Vinyl siding should also make us reconsider modifying traditional strategy and tactics. Using exterior streams as an aggressive interior attack is in progress has long been something to avoid for obvious reasons. However with the widespread use of vinyl siding, it is frequently imperative to use an exterior stream to extinguish a fast-moving fire while a simultaneous aggressive interior operation is in progress. Similarly, vinyl soffit and gable vents allow easy entry of fire venting from windows into the attic space, resulting in total destruction of the home’s contents.

|

|

| (6, 7) The vinyl siding that was autoexposed by the original fire ignited spectacularly but miraculously did not enter the gable vent or attic. Conducting an exterior and interior attack simultaneously has long been frowned on for obvious reasons. But an exterior line prevented the raging vinyl siding fire from entering the plastic gable vent and causing a total loss. Note that the stream was never directed into doors, windows, or vent openings. |

VENT-ENTER-SEARCH

The combination of faster flashovers as a result of faster heat release from hydrocarbon-based synthetic materials in the modern house and the changes in occupancy we have experienced leads one to consider the vent-enter-search (VES) method as more of a primary option for search at house fires. This is especially true for understaffed departments. VES provides a much higher degree of safety for firefighters and maintains a high level of possibility for a successful search.

|

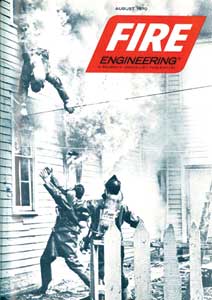

| (8) As this August 1970 Fire Engineering cover shows, flashover is nothing new. Unfortunately, our gear does not protect us from its effects-even more reason to better understand fire behavior as a proactive safety measure. (Photo courtesy of Fire Engineering.) |

Bill Gustin suggests the following reasons to consider emphasizing VES more as a primary search method at modern house fires:

- Bedrooms may not be grouped together in modern house design.

- The size of the average American house has increased significantly over the past 20 years, so it may take too long to reach the bedrooms from the front door.

- Since the lightweight structural members supporting the floor may collapse in just a few minutes under a fire load, the traditional interior route, through the front door and up the stairs, may be unsafe, and the weakness may be undetectable until it is too late [see Underwriters Laboratories/Chicago (IL) Fire Department tests on lightweight floor assemblies below].

Because of the early collapse hazard lightweight construction presents relative to VES, we should consider alternative strategies at basement fires. The internal route described above may be a suicide mission for the engine company at modern house fires.

CONFIRMING “RELIABLE” REPORTS

Another factor in effective response to modern house fires is to consider the extreme danger we place members in when we receive a report of people inside the building. In my career, I have been involved in eight search operations. During six of these dangerous operations, members risked our lives for absolutely no benefit-the home was unoccupied. In all cases, civilians reported with great confidence and apparent reliability that people were inside the burning home. It is unclear if this trend is the result of the increase in cell phone use or some other factor. With instant access to 911, civilians can report unreliable information immediately before units arrive on scene. It is clear we need to rethink exposing members to dangers based on our absolute confidence in a “reliable report” that someone is inside.

Firefighters are occupants of the structure, too. Emotions aside, we know with 100-percent confidence the house will have occupants when we send in several search crews. But how many firefighters should we risk and to what level, based on a single statement from a civilian? The obvious answer is that you base it on the situation you face. Without a doubt, when a family member or other person that you believe is reliable tells you a missing family member is inside, it is time for an aggressive search and worth the high risk to members, but we must reconsider blindly risking many members’ lives based on hearsay reports at the scene at modern house fires. As we will see later discussing key points from the UL ventilation study, unless we can get water on the fire quickly, these members are in grave danger because of rapid fire development exacerbated by modern furnishings and construction.

We get paid to take manageable risks to save lives and property. However, does our overenthusiastic ego drive us to jump at opportunities to attempt a rescue when other factors such as fire behavior, water application, and ventilation have not been considered or executed? The modern house fire is a very dangerous place, shrouded in a “home-sweet-home”-like veil and made more deadly by our lack of understanding of its hazards.

An excellent tactic applicable to modern house fires is derived from years of hazardous materials response and paramedic diagnostic training. Ask, “How do you know?” In the hazmat world, this often elicits answers like, “Well, that’s what Jimmy said.” So we get Jimmy to the command post and, sure enough, he laughs and says he never said that. What he said was something much more benign like, “I thought Danny dropped a bottle of hydrochloric acid” that was misinterpreted. “How do you know?” can prevent needless risk to our members. Asking “How do you know?” before you start the search operation could very well save you or your members’ lives.

A news article described smoke inhalation injuries to five police officers who responded to a house fire and were confronted with an occupant who stated her companion was still inside. They immediately entered the house but found no one. All five took an ambulance ride to the hospital with smoke inhalation. They did what most of us would do, immediately start an aggressive search operation. As a result, the house was definitely occupied by five people simultaneously with an uncontrolled fire. The reported trapped occupant was in the backyard. Her companion simply assumed she was inside, and the officers assumed the report was reliable. If this fire had been a little more developed and flashed over, it might very well could have cost these brave officers their lives. It may be time to apply modern thinking to modern house fires.

FIRE BEHAVIOR

There may be no better analysis and agent for change or at least motivation for you to review your current house fire strategies and tactics than Impact of Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction, a study by Steve Kerber and the Underwriters Laboratories (UL) team. This study was based around full-scale live burns in furnished test homes, conducted by fire service leaders from around the country and orchestrated by UL. The results of these fully instrumented burns illustrate how much different house fires are now than just a generation ago. Below are a few tactical considerations directly from the study to get you started to determine if your department’s house fire, training, tactics, and strategies are adequate for the modern house fire.

- “Stages of fire development-The stages of fire development change when the fire becomes ventilation limited.” For house fires, there may be a decay period, making our familiar time-temperature curve obsolete in some house fires. Soon after we force the front door, expect rapid fire development.

- “Forcing the front door is ventilation-Forcing entry has to be thought of as ventilation as well.” It seems obvious, but consider that we all try to hold off the ventilation (horizontal or vertical) until the line is ready, except when we send in search teams through the front door as quickly as possible.

- “Coordination-If you add air to the fire and don’t apply water in an appropriate time frame, the fire gets larger, and safety decreases.” Although we all know this from fireground experience, fire attack operations are not a good time to conduct research. Often, these fireground experiences develop into urban myths-not sound tactics-that we not so dutifully pass on to younger members. This may be the cornerstone of all the findings: “Taking the average time for every experiment from the time of ventilation to the time of onset of firefighter untenability conditions yields 100 seconds for the one-story house and 200 seconds for the two-story house.”

Assuming these time frames to be true, we must examine how individual departments conduct search and fire attack operations in response to modern house fires. First, should we continue to train our members to enter a burning home for search before a hoseline is operating on the fire? Do you have enough personnel to conduct both operations? Second, should we establish a training target for our engine companies to get water on the fire within these time frames?

Obviously, a few short paragraphs cannot even scratch the surface of this groundbreaking study or attempt to answer the strategic and tactical questions noted here. But you can understand the importance of this study for improving and making your department’s response to house fires safer for your members and more effective for your community.

Modern house fires are different from those of our father’s generation for a variety of well-known and not so well-known reasons. The world changes a little bit every day, but we have a knee-jerk reaction to every change. However, each day that passes that the fire service does not recognize the occurrence of significant changes and evaluate those changes relative to our operations is another day and another step we are behind the safety and success curve when we respond.

REFERENCES

Dalton, James M., Backstrom, Robert G., and Steve Kerber. “Structural Collapse: The Hidden Dangers of Residential Fires.” Fire Engineering, October 2009, 88a-88l, emberly.fireengineering.com/articles/print/volume-162/issue-10/features/structural-collapse.html.

Gallagher, Kevin A. “The Dangers of Modular Construction.”Fire Engineering, May, 2009, 95-101, emberly.fireengineering.com/articles/print/volume-162/issue-5/features/the-dangers-of-modular-construction.html.

Kerber, Steve. Impact of Fire Behavior in Legacy and Contemporary Residential Construction. Underwriters Laboratories, December 14, 2010, www.ul.com/global/documents/offerings/industries/buildingmaterials/fireservice/ventilation/DHS%202008%20Grant%20Report%20Final.pdf.

Knapp, Jerry, and Geoge Zayas. “The Dangers of Illegally Converted Private Dwellings,” Fire Engineering, June 2011, 89-101, emberly.fireengineering.com/articles/print/volume-164/issue-6/features/the-dangers-of-illegally-converted-private-dwellings.html.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, “Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/.

Putorti, A.D., et al., “Report of Test FR 3995: Santa Ana Fire Department Test at 1315 Bristol, July 14, 1994,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, August 31, 1994. http://fire.nist.gov/bfrlpubs/fire94/PDF/f94144.pdf.

United States Fire Administration, “Multiple-Fatality Fires in Residential Buildings.” Topical Fire Report Series, Vol. 9, Issue 3, April 2009, www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/v9i3.pdf.

● JERRY KNAPP is a 37-year veteran firefighter/EMT with the West Haverstraw (NY) Fire Department and a training officer at the Rockland County Fire Training Center in Pomona, New York. He is a battalion chief with the Rockland County Hazmat Task Force and a former nationally certified paramedic. He has a degree in fire protection and wrote the “Fire Attack” chapter in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II and numerous articles in fire service trade journals.

Jerry Knapp will present “Aggressive Operations at Modern Private Dwelling Fires” on Thursday, April 25, 10:30 a.m.-12:15 p.m., at FDIC 2013 in Indianapolis.

Fire Engineering Archives