BY JEFFREY A. HARWELL

The Worcester, Massachusetts, cold storage warehouse fire on December 3, 1999, in which six firefighters perished, reinforced important lessons for fighting fires in large, unsecured vacant commercial buildings. But other nonfatal fires occurring in similar occupancies offer additional lessons for firefighters regarding dangerous interior conditions.

A 1992 fire that occurred in a Fort Worth, Texas, warehouse demonstrated that any large vacant commercial building can expose firefighters to extreme and unexpected hazards on any day. The fire building was the last place firefighters expected to confront a five-alarm fire. Below is an analysis based on a review of the incident report.

BUILDING CONDITIONS, 1992

The Texas & Pacific (T&P) Railroad freight warehouse at 70 South Jennings Street is located on the southern end of the Fort Worth downtown district. The railroad built the eight-story structure with basement in 1931 to store a variety of goods and materials. The 100- × 600-foot structure took up three city blocks along Lancaster Street (photo 1).

|

| Photos by author. |

The structure featured reinforced concrete slab floors supported by reinforced concrete columns and masonry nonbearing exterior walls. Small offices were on the east end of each floor; many of them featured wood partitioning. The building originally had one passenger elevator and an adjacent stairwell (stair A) in the office area and 11 freight elevators throughout the warehouse section, numbered consecutively from 1 to 11, east to west. The freight elevators operated from the basement to the eighth floor and had seven adjacent stairwells B through G.

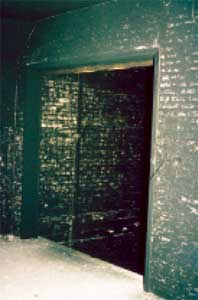

At some point, the shafts for freight elevators 8 through 11 and stairs F and G were removed, leaving two openings in the floors, each approximately 18 × 28 feet, from the basement to the eighth floor. Two steel cables were strung between adjacent columns on each side of each opening. This was the only thing to prevent a firefighter from falling into one of these openings in limited visibility conditions (photo 2). Also near these rectangular openings were several circular unprotected openings that also extended from the basement to the eighth floor, the largest one with a diameter of 1½ feet. Because these openings were at the far west end of the building, they did not play a significant role in the spread of smoke and heat; however, the openings would be a factor in search and rescue operations (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. T & P Railroad Warehouse Floor Plan |

Click to Enlarge |

| Building conditions the fire department found on arrival at the April 14, 1992, fire. (Figure courtesy of author.) |

The last tenant moved out sometime in the mid-1980s. At some point, the elevator cabs and doors ceased to function, and cabs were stopped at different locations. Freight elevator 1 figured prominently in the fire. Its cab was located in the flooded basement; its doors on the first, sixth, and eight floors were open and unprotected, presenting a serious fall hazard.

On the first floor, each freight elevator had two doors, one facing north and one facing south. At the freight elevator 1 shaft, only the north door was open (photo 3).

Freight elevators 2 and 3 figured less prominently in the fire. Freight elevator 2 was stopped on the first floor, where its north and the south doors were open. Freight elevator 3 was somewhere above the first floor. On the first floor, both the north and south side doors to freight elevator 3’s shaft were open and unprotected, presenting firefighters with another serious fall hazard into the flooded basement below (photo 4). The doors for freight elevators 2 and 3 on all other floors were closed. The status of the doors for elevators 4-7 was not recorded.

Of the building’s five remaining stairs, only stair A in the office area at the east end of the building had natural lighting and was wide enough to accommodate firefighters and their equipment. All other stairs in the warehouse section were too narrow and lacked any natural lighting.

By 1992, the building had become unsecured. Although once equipped with an automatic sprinkler and standpipe system, by the time of the fire, both systems had been out of service for a number of years with damaged piping and numerous missing sprinkler heads (photo 5).

As a result of brief walkthroughs of the building, the first-due company in 1992 was aware of building conditions at the time of the fire. A few downtown companies were also aware of building conditions as a result of responding to several smaller fires.

FIREGROUND OPERATIONS

At 5:28 p.m. on April 14, 1992, the Fort Worth Fire Alarm Office received a report of a structure fire in the vicinity of 1200 Jennings Street and dispatched a first-alarm assignment (three engines, one truck, one squad, and a battalion chief). The first-arriving company, approximately five blocks west of the address, arrived shortly thereafter and determined the correct location of the fire based on seeing the dense black smoke issuing from the upper floors of the T&P freight warehouse, a few blocks south of the initial dispatch address (photo 6).

The company proceeded to the southeast corner of the building and found an open gate that allowed access to the loading dock. Building access was not a problem, since two overhead doors at the south end were open and permitted direct access to the main body of fire. A dirt ramp had been improvised in front of one of the doors, apparently to allow vehicles to back straight into the building (photo 7).

Crews advancing handlines quickly discovered the fire involved hundreds of tires that had been illegally dumped on the east end of the first floor in the general area of freight elevator 1. Since first-alarm companies were familiar with the building, they knew that vagrants frequented the premises, especially the old office areas on the east end of each floor. So crews ascended stair A to search for possible victims on the upper floors. During the search, companies made an unusual discovery. On the second (photo 8), third, fourth, fifth, and seventh floors, they reported only minor smoke conditions, with good visibility on these floors. But on the sixth floor, they found moderate smoke conditions, whereas on the eighth floor they found severe smoke conditions with near-zero visibility. Smoke was venting through the open freight elevator 1 door on that floor (photo 9). Crews on the upper floors were also checking for any additional signs of fire since the initial size-up indicated heavy fire on the eighth floor.

A large tire fire is notoriously difficult to extinguish when it’s in an open field, and attempting to extinguish one in an enclosed concrete structure is even more challenging. Because of the number of firefighters needed to combat such a fire, additional alarms were quickly ordered, ending with the fifth alarm at 6:08 p.m.

Search and rescue operations were time consuming because of the size of the structure. There were eight floors to search, each with 60,000 square feet of floor area. Although much of the area was open space, limited visibility because of the smoke complicated search operations on the first, sixth, and eighth floors.

After crews mounted an exhausting interior attack using four 2½-inch and three 1½-inch handlines, the fire was finally declared under control at 7:05 p.m. With the fifth-alarm assignment, the total deployment included 13 engines, three truck companies, four battalion chiefs, the duty deputy chief, and two air supply trucks. Three additional companies were special-called later that night for personnel relief. Firefighters used a foam solution at one point during the fire with moderate success. Searches on the upper floors revealed no trapped occupants and no fire extension beyond the first floor.

VERTICAL SHAFTS

The open elevator doors on different floors obviously posed a severe threat to firefighting and rescue operations throughout the incident. Firefighters attacking the fire on the first floor were exposed to open shafts at freight elevators 1 and 3. Even though such a fall through these shafts would have been only one story, the greatest danger came from the flooded basement. There was no other way out of the basement once a firefighter fell into it, and the basement would have been pitch black. A firefighter falling into the basement wearing full turnout gear would be extremely disoriented at best, and drowning would be a distinct possibility.

Firefighters performing search and rescue operations on the sixth and eighth floors faced an even greater danger from the open elevator doors. Because of the heavy smoke conditions on these floors, there was a real possibility of firefighters wandering into the elevator shafts in near-zero visibility during their search operations. Even if a firefighter survived the fall, it’s likely that member would have drowned in the flooded basement.

Luckily, no firefighters strayed into the open elevator doors during this fire, although there were several close calls. A few firefighters did receive minor injuries; one involved a piece of spalled concrete striking a firefighter in the head (see photo 5).

Despite the dangers the open elevator shafts presented, they did create one advantage for firefighting efforts. The wind, which was out of the south at 13 miles per hour (mph), traveled horizontally through the open overhead doors on the south side of the building and into the fire area. From this point, the wind pushed the smoke vertically upward through the open shaft of freight elevator 1, and most of it vented at the eighth floor, where the smoke exited through various openings to the outside. Less smoke vented on the sixth floor through the open elevator door. Thus, firefighters did not face the problems normally associated with vertically ventilating a concrete structure.

This fire clearly demonstrated the importance of protecting vertical openings in a multistory building. On the sixth floor and especially on the eighth floor, where elevator doors were open, heavy smoke quickly entered these floors and made conditions untenable for any occupants. Also, on the eighth floor, an open door to stair A allowed smoke to enter the stairwell and make conditions in the upper portions of the stairwell untenable for any occupants depending on this stair for escape (photo 10). On the second through the fifth floors and on the seventh floor, where freight elevator 1’s doors were closed, conditions remained tenable throughout the fire for any possible occupants. As previously indicated, the heavy smoke on the sixth and eighth floors increased the likelihood of firefighters wandering into the open elevator shaft during search operations accidentally.

Because the open elevator doors provided ample ventilation during the early stages of the fire, cross ventilation was not carried out immediately. However, once the fire started to darken down somewhat, interior companies on the first floor began to report increased heat in the fire area, a result of the “stack effect” of the smoke in the vertical shaft. As the size of the fire decreased, the smoke cooled, eventually becoming stagnant in the shaft, and vertical ventilation ceased. Several of the first-floor overhead doors had to be opened quickly on the north side of the building to provide cross ventilation.

Firefighter access to the upper floors of the building was limited to stair A in the office area, which was the only one wide enough for firefighters with turnout gear to use and had natural lighting from the exterior. All other stairs located in the warehouse area were too narrow for firefighters to use and had no natural lighting, so they were pitch dark even in the middle of the day. To expedite operations and keep the single stairway from overcrowding, an aerial platform was raised as high as it would go, and firefighters were deposited on the sixth floor so they could search the upper floors and then work their way down using stair A (photo 11).

Although the large openings present at the west end of the building didn’t play a major role in venting smoke and heat vertically, they did come into play during search and rescue operations. All portions of the building had to be searched. Visibility was reduced on floors where smoke was present. Had the fire occurred at night, visibility would have been zero on all floors. The scenario of a firefighter accidentally crawling underneath one of the cables protecting these openings was a distinct possibility (see photo 2). As with open elevator doors, a firefighter falling into one of these openings would have landed in the flooded basement. Some of the smaller circular openings could have also caused leg injuries to firefighters.

EFFECTIVE PREPLANNING

Although the first-due company had made brief walking tours of the building since it had become unsecured and several downtown companies were aware of existing building conditions from previous fire responses to the site, there was no written preplan. Hence, once the incident escalated beyond the normal first-alarm assignment, all additional companies had to rely on verbal warnings about hazardous building conditions by radio or face to face from personnel already on scene. If any of these multialarm companies missed these warnings, they would be in deep trouble.

This fire also illustrated the need to expect the unexpected. In previous walk-throughs, the first-due company assumed any fire in this building would be rather small, based on the limited amount of combustible materials present in an otherwise fire-resistive building. The only fire scenario that seemed possible would be a small fire at the east end of the building involving the wood paneling in the office areas and any combustibles left by the homeless population.

The illegal dumping of tires on the first floor obviously changed conditions drastically. The flooded basement would normally not be considered a firefighting hazard for a prefire plan, but because of the open elevator shafts, it suddenly became a very big issue.

Figure 1 was prepared shortly after the fire to be distributed to all Fort Worth fire stations as part of a prefire plan package, which included a written description of the 1992 fire, the lessons learned, and the current condition of the building for any future incidents.

Why was this important? Two months after the fire, personnel from the fire marshal’s office discovered tires were once again being dumped inside and outside of the building (see photo 7). Efforts by the city to force the owner to secure the building had obviously been unsuccessful. A scenario similar to the April 14, 1992, fire was a distinct possibility, and fire companies citywide had to become familiar with building conditions.

Eventually, city crews were called in to haul off the tires and secure the building to prevent a repeat of the April 14 fire. Nineteen years later, the building is still standing. Other than for a small portion of the building that is used for an occasional haunted house, it remains vacant. At last check, the current owner is doing a good job of keeping the building secure (photo 12).

LESSONS LEARNED OR REINFORCED

- Develop and make available to all companies an effective preplan system for all commercial buildings, particularly for vacant high-rise buildings that pose an increased danger to firefighters.

- Other companies beyond the first-alarm assignment must become familiar with hazardous buildings such as this. The fifth-alarm assignment drew companies from well beyond the downtown area.

- Early cross ventilation in vacant high-rise buildings such as the T&P warehouse is beneficial to interior attack companies once vertical ventilation ceases to be effective. Had the elevator doors on various floors not been open, cross ventilation would have been an immediate necessity.

- When buildings become unsecured, all floors must be searched during a fire for possible trapped occupants. Since a number of firefighters have perished while searching for victims in vacant structures, it is imperative to secure the building as soon as possible.

- This fire never posed a significant risk of structural collapse despite the heavy fire conditions on arrival. Buildings featuring reinforced concrete construction throughout usually pose little risk of major structural collapse. The greater danger to firefighters came from spalling concrete.

- Prefire plans must take into account stairwell conditions and width. Even though this building was 600 feet long, only one stairwell was wide enough for firefighter use.

- Prefire plans must evaluate the status of sprinkler and standpipe systems in vacant structures. The first-due company was familiar enough with the building to know that pumping the sprinkler/standpipe connections would have been ineffective in this fire.

- Based on the previous two items, prefire plans must allocate an aerial to be used to transport firefighters to the upper floors to facilitate search and rescue operations simultaneously from the top and bottom of the building. Had any fire been discovered on the upper floors, the aerials could also have provided a water supply manifold, since the building’s standpipe system was totally out of service.

- A 360° assessment is critical during the early stages of an incident for fires such as this. One vantage point would seem to clearly indicate a working fire on the eighth floor, yet a view from the south side of the fire building clearly shows a working fire on the first floor.