BY JOSEPH R. POLENZANI

Mobile homes are a part of the American landscape. In 2007 alone, more than 95,000 manufactured homes were shipped nationwide.1 Manufactured housing also accounts for approximately 10 percent of the single-family structures in the United States.2 Despite the fact that we drive by them, respond to medical calls in them, and sometimes live in them, we often overlook mobile homes when it comes to training and prefire planning. However, as the deaths of two firefighters in Craigsville, West Virginia, last February showed, mobile homes can pose significant, and sometimes deadly, challenges. A better understanding of mobile home design and some common hazards can give firefighters an advantage when it comes to safely and effectively operating in this unique environment.

FACTORY-BUILT HOUSING

Mobile homes, more properly called “manufactured homes,” make up one of the two broad categories of factory-built housing. Factory-built houses are different from site-built homes in that that structure’s major components are fabricated in a remote facility and then assembled on the buyer’s property. In the case of manufactured homes, the entire structure is transported to the site, generally in one or two pieces. Manufactured homes typically retain their frame and axle assemblies after installation and are often secured in place with undercarriage tie-down straps instead of a traditional foundation (photo 1).

All new manufactured homes leased or sold in the United States must comply with the National Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974, also called the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Code. The HUD Code is unique in that it is a preemptive national building code, which allows manufacturers to sell their homes in any state, regardless of local building codes. State and local governments may regulate the placement of manufactured homes through land use or zoning ordinances. However, in most cases, these laws may not discriminate between manufactured housing and traditional site-built homes.

The term “mobile home” is most properly used to describe transportable manufactured houses built before June 15, 1976, the HUD Code’s effective date. Prior to the adoption of the HUD Code, mobile homes were built to a variety of voluntary industry standards, which were not uniformly enforced on a national level. For the purposes of this article, we will use the terms interchangeably, since the concepts discussed apply to both pre- and post-HUD Code structures.

The other category of factory-built housing includes modular, panelized, or precut structures, which are removed from their transport assemblies and assembled on-site over a slab or poured foundation. Like ordinary wood-framed houses, these homes are considered permanent structures and must comply with local building codes. Modular or panelized homes are generally larger than manufactured homes and, once completed, are often indistinguishable from site-built structures.

SEPARATING MYTH FROM FACT

Before discussing tactics for dealing with fires in mobile homes, we need to dispel some common fire service myths concerning these structures.

MYTH: Mobile homes are found only in rural areas.

FACT: Although most common in suburban or rural environments, 24 percent of manufactured homes are in population markets of more than two million people. In fact, the current demand for affordable housing may soon increase the number of mobile homes found in urban neighborhoods. Additionally, new designs and technology that allow mobile homes to closely resemble traditional one- or two-story houses may lead to their acceptance in more densely populated areas.

MYTH: A mobile home fire is always a defensive operation.

FACT: With timely notification and response, offensive operations are possible. As with any small structure, an unchecked fire can quickly spread throughout the entire house. However, this problem is not unique to manufactured homes. Interestingly, some newer or well-maintained mobile homes are so weather-tight that fires can be reduced to a smoldering state by the lack of oxygen. Although this stops the fire from spreading, aggressive ventilation can cause the fire to quickly return to its previous size.

A case in point: A number of years ago, my engine company responded to a reported structure fire in a single-wide mobile home, near the center of town. We arrived to find smoke coming from a bathroom window on the A side and some scorch marks on the siding. As we advanced the first line through the front door, we encountered thick smoke, low visibility, and moderate heat. All exterior clues pointed to a fire in the B side bedroom/bathroom area, so we turned left and made our way across the kitchen and into the rear hall, intending to reach the bathroom and open the home’s rear (C side) door. As the other crew started ventilation, visibility improved enough for us to see that there was no fire in the bathroom or bedroom. Before I had time to puzzle this out, I felt something hitting me (hard!) on the back of the helmet. I turned and found myself face piece to face piece with a chief, who was yelling, “It’s behind you, stupid!” Apparently, we had passed right by the smoldering fire in the kitchen [this was in the pre-thermal imaging camera (TIC) days]; the ventilation had caused the fire to flare up behind us. We quickly reversed course in the narrow hallway and knocked down the fire. Lesson learned: Despite the fact that true fireground backdrafts are uncommon, firefighters must be careful any time they encounter a mobile home that shows evidence of smoke or high heat levels but no active fire.

MYTH: Manufactured homes are “built to burn.”

FACT: According to a 2005 National Fire Protection Association report, during the mid-1990s, manufactured homes had a fire rate per 100,000 housing units that was 38 to 44 percent lower than the rate for other dwellings.3 The federal standards regulating manufactured housing design and construction include flame resistance and other fire safety requirements for structural and finishing materials. The HUD Code also sets performance standards for the heating and electrical systems.

So why, then, do mobile homes seem to burn up so quickly? Much of the answer to that question has to do with age and maintenance. In 2007, more than 22 percent of the mobile homes still in use were manufactured prior to 1975. (2) Although mobile homes are safe structures as delivered from the factory, neglect, repeated moves, or years of exposure to the elements can compromise the integrity of the house’s protective components. In a fire, unprotected openings create an opportunity for flames to spread through void spaces, quickly consuming the small-dimension lumber and engineered wood products that support the home (photo 2). In colder climates, many owners also improperly install or neglect to replace pipe-warming heat tape, which is designed to last only for three to five years, resulting in undetected overheating or electrical shorts.

HAZARDS ASSOCIATED WITH MOBILE HOMES

Owner modification can be one of the most serious hazards associated with mobile homes. One of the few advantages to fighting fires in manufactured houses is that they are built using a limited number of standard floor plans. For example, in most one-piece homes, the front door will be located on the A side, often toward the D side (Figure 1). As in traditional homes, entering the front door will put you in the main living area. A kitchen or a bedroom will be to the immediate right. If a bedroom is on the right (D side), the kitchen will be to the left. If the living room opens into a kitchen on the right, there most likely will be two or more bedrooms and a bathroom to the left, accessed through the rear hallway (C side). In either case, the larger (master) bedroom will usually be at the opposite end from the front door, close to the back door. A quick glance at the home’s windows during size-up will often allow you to complete your mental map before even setting foot in the structure.

Unfortunately, since manufactured homes are designed to be relatively small and portable, many homeowners will try to increase usable space by adding rooms, removing walls, or even combining the home with other structures (photo 3). Although the HUD Code regulates design and construction of manufactured homes, most jurisdictions require that additions built on-site must go through the regular permitting process and comply with local building codes. Despite these requirements, many of the do-it-yourself additions found on these homes have been built “under the radar” in areas where code enforcement is lax or nonexistent. The resulting structures may contain hidden void spaces, walls in unexpected places, or rooms with no second means of egress.

On January 11, 2001, Lt. John White of the Rocky Grove (PA) Volunteer Fire Department died after becoming disoriented during a structure fire inside a heavily modified manufactured home (photo 4). He was eventually found in a 12- × 12-foot room, which had been added to the A/D corner of the structure. The room did not have any exterior doors but did contain a stairway leading down to a walkout basement/workshop/garage, which had exits only at the B end of the structure.

One less common, but dangerous, modification is the addition of a pitched roof over the flat metal roof of a single-wide trailer. This second roof creates a void space that may not be accessible from inside the residence, making fire attack difficult. If the homeowner has cut an access hatch through the roof and into the newly created “attic,” he has already compromised the home’s structural integrity even before a fire begins. Although some mobile homes are built with pitched roofs, any roof that appears to be of a different age or material from the rest of the home should be suspect.

Although we preach the importance of a complete size-up on all incidents, the small size and perceived simplicity of mobile homes can make us complacent. Take the time to do a complete walk-around, noting entry and exit points, signs of occupancy, fire and smoke, utilities, and so on. A complete 360° size-up may also alert you to possible structural issues, such as altered, weakened, or hidden areas. Remember, the performance of these modified dwellings when exposed to fire is unpredictable at best.

If a TIC is available, it can be used as part of the exterior size-up. Entry teams should also conduct their own size-up by performing a complete six-point scan of the interior (sweep the ceiling left to right, eye-level left to right, and floor left to right), especially in modified homes. A TIC may reveal fire hiding in voids above or below the crew.

Another common hazard is undercarriage storage. Because mobile homes have a limited amount of usable space, people often use the undercarriage area for storage (photo 5). Common items found in these spaces include fuel, lawn equipment, tires (both the house’s and others), and furniture. All of these items contribute to the building’s fire load. If a fire starts in the undercarriage area of a trailer, it can easily spread along the underside of the floor and into the living area. Responding firefighters entering the home could immediately find themselves on an unstable floor over a growing hydrocarbon-fueled fire. In rural areas, you may even find illegal materials such as explosives or meth lab supplies, either of which can turn a “routine” structure fire into a dangerous hazmat incident.

Although mobile homes are occasionally installed over basements or crawl space foundations, manufactured homes are typically supported by piers made from solid concrete blocks, concrete blocks with cells, adjustable metal jack stands, or a combination of the above materials. These piers, in turn, should be set on concrete, wood, or ABS footings, which serve to distribute the home’s weight. A series of metal anchor straps, running diagonally or vertically between the chassis and the ground, stabilizes the house against wind. Make a point of accessing the undercarriage area as part of your size-up. Many of these spaces are protected by a piece of plywood, either leaning against the home’s metal skirt or set into hinges. You can quickly remove locking devices, such as padlocked bolts or hasps, with a halligan tool (you did bring a tool, right?), allowing a look underneath the home. If there is no access panel, remove a section of the metal skirt using the spike of a halligan, an ax pick, or a similar tool to penetrate the sheet metal and pull it down and away from the upper trim.

Elevation and terrain can also pose unforeseen challenges for firefighters. In many areas, manufactured homes are marketed as “affordable housing.” As a result, they are often found on “affordable” lots. Simple economics dictate that sloping or uneven parcels of land will usually be less expensive than flat, easily accessible ones. When a new house is built on-site, it can be adapted to suit the lot through the use of decks, walk-out basements, or other custom-design features. Manufactured homes, however, are placed on the lot after they are built. Creative installation techniques are sometimes required to fit a manufactured house onto the owner’s property, resulting in access problems for emergency responders (photo 6). In flood-prone areas (which, unfortunately, are also typically less expensive), mobile homes may be elevated to keep them dry (photo 7).

In these situations, it is safest to treat the incident as a second-story fire. As always, perform a complete 360° size-up to identify all potential problems. If you can see underneath the home, check the integrity of the floor and its support structure prior to entry. If the area beneath the home is being used for storage or as a carport, clearly identify each division or sector over the radio, to avoid confusion. In our department, Division 1 is the first floor, Division 2 is the second floor, and so forth. If the house is 10 feet off the ground, is the main floor still Division 1? Make sure everybody knows the answer to this question before they enter the structure.

Plan ahead for a second entry or exit point before it’s needed. Pay close attention to the back door, and communicate any hazards, such as drop-offs or missing stairs. It’s not uncommon for the rear stairs on mobile homes to be unstable, off center, or missing completely. Even if the home is at ground level, the three- to six-foot drop can still cause serious injuries to an unsuspecting firefighter. The back door in photos 6 and 7 may be the only means of escape for a lost or trapped firefighter. Can you force a door while standing on a ground ladder? How long will it take, and how many personnel and ladders will you need? In extreme cases, a risk/benefit analysis may dictate defensive operations if the home is confirmed to be unoccupied.

FIREFIGHTING TACTICS

Fire attack. Approach a fire in a manufactured home with the same respect you give a larger, site-built house. Don’t get caught in the trap of underestimating your water or personnel needs because “it’s only a trailer.” A safe and successful attack on the fire requires a reliable supply of water and the ability to deliver it effectively. My former volunteer department has used a two-inch preconnect with a one-inch smooth-bore tip for many years. This line delivers about 200 gallons per minute (gpm) and is still maneuverable by two or three firefighters. The effectiveness of this higher-flow line makes it a good choice, even in the relatively tight spaces of a mobile home. If it can be confirmed that the home is unoccupied, an indirect fog attack from the exterior is also a viable option, especially if there are not enough personnel on scene to safely support a direct interior attack. Some departments have even reported success using a piercing nozzle to apply water directly into burning rooms through the home’s lightweight skin.

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV). Because of manufactured housing’s lightweight design, vertical ventilation is rarely a safe option. For those departments that use it, PPV can be extremely effective in mobile homes. PPV will quickly remove the smoke and heat from the small interior space of a mobile home, improving visibility and increasing firefighter safety. As always, however, ventilation tactics must be properly coordinated with fire attack to avoid placing crews between the fire and the exhaust opening. The 360° size-up can often give a good idea of the fire’s location and potential exhaust openings.

Aggressive overhaul.Overhaul in manufactured housing must be immediate and thorough. Once exposed to flames, the home’s small structural members quickly lose strength and can become dangerously unstable. After the main fire has been knocked down, carefully check the areas above, below, and adjacent to the fire compartment for extension. This task may involve cutting through the floor or even gutting sections of the structure. If there is any evidence of fire damage in the undercarriage area, you may need to reinforce the floor to safely work in the living space. Once extinguishment is confirmed, roof ladders or solid doors can be used to support firefighters’ weight during salvage and overhaul. Overhaul of undercarriage areas (especially those used for storage) can be extremely time-consuming. Remember, it’s okay to call mutual aid for any stage of a fire, including overhaul, if needed.

RIT

Rapid intervention team (RIT) operations in mobile homes present their own challenges. Locating and removing a firefighter from a 14- × 60-foot structure may sound simple, but small rooms, narrow hallways, and small windows are coupled with lightweight construction. Adopt a proactive RIT philosophy; otherwise, crews will be playing catch-up if something goes wrong.

As with fire attack, a 360° size-up is the foundation for safe RIT operations. While the team members are staging appropriate tools, the RIT officer should get a complete view of the structure, using exterior cues, such as windows and doors, to start visualizing the home’s layout. Priority should be given to locating and opening exit points. In some cases, this may mean clearing debris from the area below the back door or identifying windows for crews to use in an emergency. If parts of the home are well above ground level, place ladders at doors and windows as soon as possible, and communicate their locations to Command. A second company may be needed to assist with these activities. Although personnel are often in short supply on the fireground, it’s better to commit a company as part of an operational plan than to scramble to find one to assist with an unplanned emergency rescue. It’s also essential to access the underside of the house. Remove as much of the skirting as is practical, monitor structural stability, and determine what obstacles are between rescue crews and a firefighter who falls through the floor (photo 8). Make plans to perform a rescue in any part of the structure well before a Mayday is called.

RIT crews operating in mobile homes must also be trained to operate in tight spaces. Training exercises like the Pittsburgh Drill and the Denver Drill, which require students to move downed firefighters in limited space, are excellent preparation for working in mobile homes. Additional training in techniques for moving firefighters down ladders or quickly removing them from below the floor is also beneficial.

MOBILE HOME COMMUNITIES

In addition to the challenges presented by individual manufactured homes, fires in mobile home communities or trailer parks present their own difficulties. Tactics we use in neighborhoods filled with site-built homes on half-acre lots may not be the best choice for closely spaced mobile homes. Limited access, poor water supply, and multiple exposures can make operations in these areas extremely difficult. Thorough preplanning gives you the best odds of overcoming each of these problems.

Access. Many mobile home communities are built on private property, with lots leased to homeowners or trailers rented by the month. Although local codes can regulate the layout of newer developments, the access roads and driveways in older parks may not conform to the design, size, and signage requirements that apply to regular streets in your area. Property owners have a financial incentive to keep things tight: Narrow roads cost less to pave and allow more space for revenue-generating home lots. In rural areas, the access roads may not be paved at all, creating problems for heavy apparatus or vehicles with limited ground clearance. In extremely rough or mud-prone areas, you may even need to plan for a four-wheel-drive pumper or brush truck to respond on the first alarm.

The only way to be sure that your apparatus can reach all of the homes in a community is to drive through and check. It’s a good idea to do this at least twice, once during the day and once at night. A daytime preplanning trip will allow you to visually evaluate the condition of road surfaces prior to putting your apparatus on them during an emergency. The daytime visit also gives you an opportunity to determine whether delivery trucks, lawn care trailers, or other service vehicles park on the street, blocking the passage of large fire apparatus.

The nighttime trip allows you to see how the parking situation changes when most of the residents are home. With their emphasis on efficient use of space, most mobile home lots aren’t designed to accommodate more than a couple of cars. As a result, vehicles may be parked in streets, cul-de-sacs, or other nondesignated areas, creating access problems for emergency responders. In cases of severe congestion, it may be necessary to stage responding apparatus nearby and have personnel proceed to the scene on foot. During both trips, make notes of unusual road features, such as harsh speed bumps, and areas where children regularly play in the street.

Utilities. As with any structure fire, control of utilities should be an early priority. Modern mobile homes are wired for 40- or 50-ampere 125/250-volt electrical power. Manufactured homes are required to have a master electrical service disconnect. However, this switch may be incorporated into the home’s breaker panel and may be accessible only from inside the structure. Mobile homes in more temporary environments, such as trailer parks, tend to receive their power through a manufacturer-supplied power cord, which is connected to a freestanding meter pedestal next to the home. These pedestals often contain a main disconnect, which can be used to shut off power to the house.

Natural gas service can usually be shut off at the meter. In mobile home communities, one meter pad, located in a common area, may contain the gas meters for two or more homes. Propane (liquid petroleum gas) may be supplied to the home from a large detached tank or smaller onboard tanks, which are mounted on the trailer’s A-frame or, less commonly, in an exterior compartment. In either case, there should be a shutoff valve (or valves) for stopping the flow of gas into the structure.

Signage. It’s not uncommon for mobile home communities, especially those that are not regulated by local codes, to have little or no signage to assist emergency responders in locating a call (photo 9). In larger communities, you may encounter hundreds of trailers filling the equivalent of multiple blocks with no street signs or other markers. Lot-numbering systems can also be confusing and don’t always follow a discernable pattern.

A good map book is essential for operating in these environments. During your preplan trips, take time to note entry and exit routes, lot numbers, and landmarks (clubhouse, swimming pool, manager’s office, and so forth). All of this information should then be transferred to maps and made available to dispatchers, drivers, and company officers. Even if the streets aren’t marked, verbal directions from Dispatch such as “Enter the park from Atkinson Road, take the first right, and then the second left” can save valuable time. In smaller parks, individual lot numbers can often be displayed on the map. For larger communities, however, you may have room to show only a range of addresses. Even this limited information can be helpful, though. By knowing the format of the house or lot numbers in a specific area, you have a better chance of recognizing incorrect numbers, whether they’re given to you by Dispatch or marked on the homes themselves (photo 10). In communities where the internal “streets” are named, you’re likely to find street addresses instead of lot numbers, which makes mapping and navigation easier.

Water Supply. As in other residential areas, water supplies in mobile home communities can range from Class AA (blue top) hydrants every 500 feet to nothing at all. For departments that normally rely on hydrants as a water source, the water supply systems in many trailer parks can hold some unpleasant surprises. One of the most dangerous assumptions firefighters make when working in these communities is that they are using their regular municipal or utility-owned hydrant system. In fact, because many mobile home communities are private property, the hydrants are part of a private water system. These private hydrants may not always be located, marked, or maintained in the same way as public hydrants.

As part of your preplanning, determine which type of water system is present. One good clue is a master water meter or backflow prevention device enclosure (also known as a Hot Box®4) at the entrance to the community (photo 11). On most public water systems, private homes and business are required to have a backflow preventer installed if irrigation, fire suppression, or other specialty systems are run off the regular water line. If the buildings, homes, or lots in a park have their own small backflow preventers, odds are good that they are on a regular public water grid. However, if there is only one large device for the entire complex, you’re probably dealing with a metered, private system.

Hydrant color can be another indicator, but only if you’re in a jurisdiction that mandates a certain color for private hydrants. National Fire Protection Association 291, Recommended Practice for Fire Flow Testing and Marking of Hydrants, allows property owners to mark private hydrants within private enclosures at their discretion. For private hydrants that are on public streets, NFPA 291 recommends that they be painted a color that distinguishes them from public hydrants. Unfortunately, not all cities or utility districts use a hydrant color scheme or even paint their hydrants on a regular basis. In many cases, well-intentioned property owners simply paint their private hydrants to match the public ones they see up the street, so be careful when using color as a guide.

Problems with private fire hydrants generally involve two things: location and capacity. Unless your local government does a good job with planning and codes enforcement, you may find private hydrants almost anywhere (photo 12). This is another reason preplanning is essential. Take the time to locate all hydrants and mark them in your map book. If the hydrant is in a really unusual location, you may even want to include a note, such as, “Hydrant is behind the house in Lot 32.” Note also any unusual obstacles, such as fences, dogs, or obstructions.

Private hydrants may also deliver less water than expected. Water-control devices, like the one in photo 11, can create a choke point for water entering a larger community, reducing large-diameter public mains down to a four- or five-inch pipe. The private water mains inside a complex may also be undersized or poorly designed, substantially reducing the volume of water available. The last public hydrant before the water meter shown in the photo has a rated capacity of 750 gpm. The two private hydrants inside the complex can barely discharge 400 gpm. If possible, flow test private hydrants at least once a year and note the results in your map books. This information is especially important if the private hydrants’ capacities are significantly different from those of public hydrants in the same area. Regular flow testing will also help you spot any changes in the water system. If the water supply for an entire mobile home community is run through one water meter, a partially closed meter valve or street valve will drastically reduce the amount of water available for domestic use and firefighting.

If flow testing is not possible, visually check the position of the valves to ensure that the system will deliver its maximum capacity. Also remember, many mobile home communities are owned by companies or people who live off-site, in another city, or even in another state. If the water bill is not paid, the local utility company can shut off service to the entire complex, rendering the private hydrants useless.

Even if your department is used to establishing its own water supply with tanker shuttles or on-scene drafting, getting water to the fire scene in a mobile home community can still be a challenge. Narrow access roads, speed bumps, or poor street surfaces slow tanker operations, and the small lot sizes often leave no room to set up portable ponds without completely blocking the road. In many cases, the best solution is to bring water in from off-property. This may be done by setting up a dump site outside the complex’s entrance or by pumping from the nearest public hydrant. Either way, you might be looking at a long hoseline lay to get the water to where you need it.

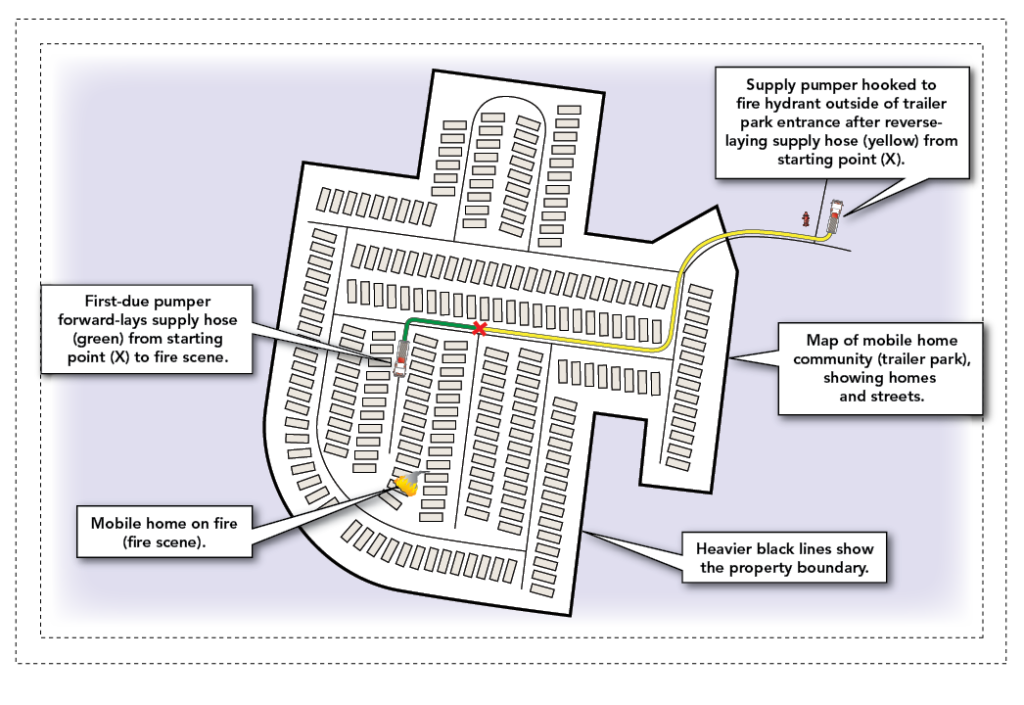

Depending on the distances involved and the size of your department’s supply hose, you may need to plan for a relay pumping operation. Other times, a split lay, with one pumper forward-laying to the scene and another reverse-laying to the hydrant, is the most effective option. One trick savvy rural departments use is to premeasure long hoselays and identify supply hose drop points and pump positions ahead of time. These points are then marked with roadside signs, reflective markers, or lines painted on the road’s surface. This method can be used very effectively in larger mobile home communities when water must be brought into the complex from off-site. A central “layout” starting point for the reverse-laying pumper is marked, as deep into the property as the unit’s supply bed will allow. From that point, the forward-laying pumper can proceed in any direction needed to reach the fire scene (Figure 2).

A side benefit to preplanning your water supply is the ability to plan for apparatus access. Many of us are used to operating on two-lane (or larger) streets. In these circumstances, filling up one lane with long “S”s of large-diameter hose is usually not enough to bring operations to a halt. However, if the first-in pumper drops a line down the middle of a single-lane access road, it may be the only piece of apparatus that makes it to the scene. With a firm road shoulder or crews to drag hose, you may be able to run your supply hose out of the way, along the edge of the road. Otherwise, if your department runs engines with large booster tanks or pumper/tankers, consider sending the first unit in “dry” and letting the second-due engine company forward- or reverse-lay a supply line once other apparatus have made it in to the scene (photo 13). If you’re short-staffed or a second-due engine isn’t always guaranteed, the best option may be to drop a wyed leader line or courtyard pack at the scene and reverse-lay to the water source. In the worst cases, hand-jacking a leader line the last few yards may be the only option when ground conditions don’t allow your apparatus to reach the fire scene. Regardless of what your department “always” does, don’t be afraid to think outside the box when it comes to establishing a water supply in these situations. [See “Mobile Home Fires, Parts 1 and 2,” by Bill Gustin (Fire Engineering, April and May 2004).]

Exposures. As with the roads and water supplies, the small lot sizes in many mobile home communities may have been “grandfathered” into your community and are, therefore, exempt from spacing requirements or lot line setbacks. Closely spaced mobile homes present a serious exposure problem, especially for departments without immediate access to a high-volume water supply.

In addition to parked vehicles and the homes themselves, there are two common exposure hazards in high-density mobile home communities—decks and storage buildings. Homeowners often add porches or decks to their manufactured home as a cost-efficient way to increase usable space. Despite the fact that these additions are not covered under the HUD Code and should be built to local standards, they are often erected without a permit and made from raw lumber, without any sort of fire retardant treatment (photo 14). In a crowded mobile home park, these structures can act as combustible bridges, spanning the already narrow gap between homes.

Storage buildings can take the form of prefabricated metal sheds, Dutch barns, and even homemade structures. These small buildings often take the place of traditional garages that store lawnmowers and other engine-powered equipment; fuels; pesticides and chemicals; grills with propane tanks or lighter fluid; extra furniture; and anything else that a resident doesn’t want inside the home’s living area. Some of these items can be seen sitting next to the storage sheds shown in photo 12.

Storage buildings situated near or against a mobile home can also make access to the house difficult, preventing firefighters from reaching parts of the home with hose streams or tools. In some cases, larger sheds or tall Dutch barns may completely cover one or more of the trailer’s windows (photo 15). Firefighters accustomed to having a second way out of bedrooms and other spaces may find themselves trapped if interior conditions deteriorate. During your 360° walk-around, take a moment to study the home’s layout. If a storage building interferes with points of entry or exit, be sure that the incident commander (IC) and all interior crews are made aware of it. As with undercarriage storage, investigate these buildings early, and be sure to factor both the building and its contents into your fire, RIT, and exposure-control plans.

Many departments have found success using Class A foam, especially with compressed-air foam systems, to protect exposures when water is at a premium. When properly applied, the foam provides an insulating barrier between the exposed surface and the fire. It also reduces the water’s surface tension and allows the water to more effectively soak into the potential fuel. However, when using Class A foam for exposure protection, it’s important to carefully read the manufacturer’s usage guidelines. Some brands of foam are designed to be applied at a higher percentage rate when used for exposure protection.

In Firefighting Principles & Practices, Second Edition, William Clark states: “Officers who have never had a fire extend to an exposure are not as inclined to expect it as those who have experienced it.”5 Clark also discusses three reasons controllable fires become multistructure conflagrations: failing to protect exposures, making a weak initial attack (i.e., small hoselines and insufficient volume of water), and not taking precautions with brands that are flying downwind. For officers who regularly handle stand-alone mobile home fires with a single line and a limited water supply, all three of these factors are strong possibilities when operating in mobile home communities. Do not underestimate the potential of these fires or the amount of resources that may be needed to contain them. It’s imperative that the first-arriving company officer perform a thorough, realistic size-up and develop plans for the best- and worst-case scenarios.

Although they are often overshadowed by larger, more expensive residences, manufactured homes deserve our attention when it comes to training, preplanning, and responding. Don’t get caught in the trap of discounting the dangers posed by these structures. The Ol’ Professor, Francis L. Brannigan, used to say, “The building is your enemy: Know your enemy.” This is still true today, even if the enemy has wheels.

Endnotes

1. “Quick Facts 2010: Trends and Information about the Manufactured Housing Industry,” Manufactured Housing Institute, 2010.

2. American Housing Survey for the United States: 2007, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Housing Reports, Series H150/07, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20401, 2008.

3. Manufactured Home Fires in the U.S., Dr. John R. Hall Jr., National Fire Protection Association, 2005.

4. Hot Box is a registered trademark of CDR Systems Corporation, Jacksonville, Florida.

5. Clark, William E. Firefighting Principles & Practices, Second Edition. (Saddle Brook: Fire Engineering Books & Videos, 1991).

Manufactured Housing Links

- Manufactured Housing Statute (“HUD Code”): http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_01/24cfr3280_01.html/.

- 24 CFR 3280 Manufactured Housing Standards: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_01/24cfr3280_01.html/.

- 24 CFR 3282 Manufactured Housing Regulations: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_08/24cfr3282_08.html/.

- 24 CFR 3285 Manufactured Home Installation Standards: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_08/24cfr3285_08.html/.

- HUD Manufactured Home Consumer Q&A: http://www.hud.gov/offices/hsg/sfh/mhs/mhcqa.cfm/.

● JOSEPH R. POLENZANI is a 17-year veteran of the fire service and a captain with the Franklin (TN) Fire Department. He is chairman of Franklin’s training committee and a recruit instructor. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire administration and is a certified fire officer II, safety officer, instructor, and National Registry EMT-IV. He has presented at FDIC and is a member of the International Society of Fire Service Instructors.