Photo by John Axford.

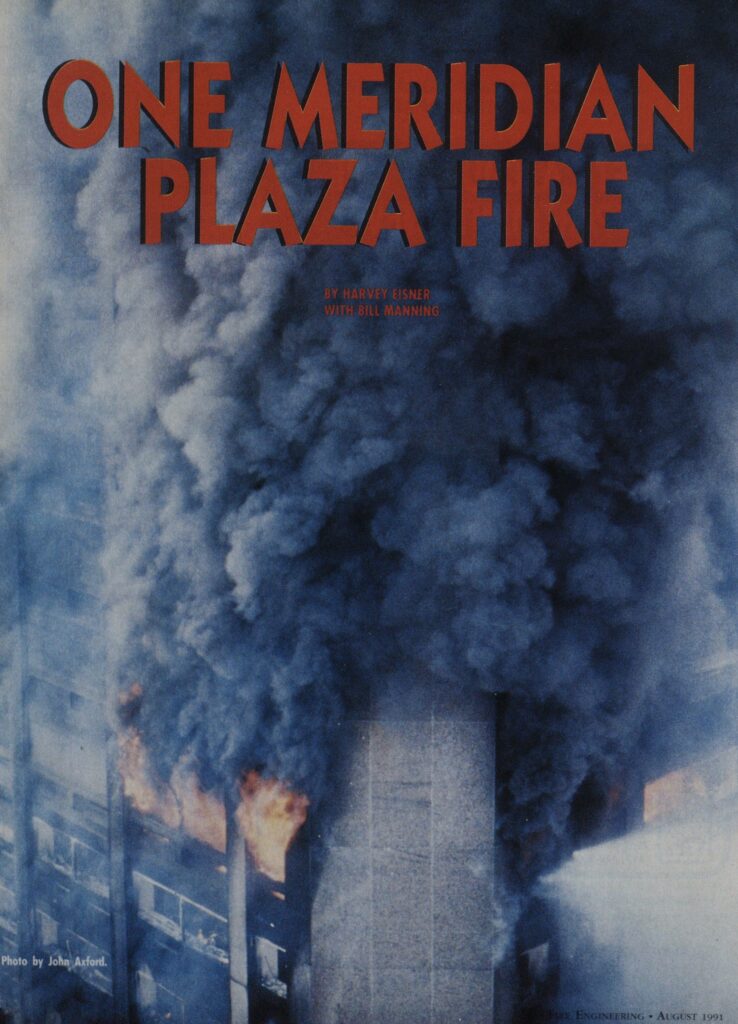

On the night of Saturday, February 23, 1991, fire struck One Meridian Plaza in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was to become one of the worst highrise fires in history. Three firefighters died and 24 were injured. Nine floors of the 38-story office building were completely destroyed, causing millions of dollars in damage. Operations and logistics were severely hampered by failure of major building operating systems: main electrical power, emergency generator power, and, most important, water pressure from the standpipe system. Rapid fire spread required a massive mobilization of firefighting forces. Hours into the operation, the advancement of the fire, the toll it took on firefighters, and the possibility of a major structural collapse forced withdrawal of personnel from the building. The fire burned freely until extinguished by automatic sprinklers on an upper floor, fed by department pumpers through the standpipe system.

RELATED

SOME OPERATIONAL LESSONS LEARNED FROM ONE MERIDIAN PLAZA

HIGH-RISE OPERATIONS: SURVIVING ABOVE THE FIRE

The Art of Building Intelligence: Preparing High-Rise Operational Battle Plans

High-Rise Firefighting Lessons Learned

THE BUILDING

The 38-story Meridian Building, the eighth tallest of approximately 500 Philadelphia high-rise buildings (6 stories/75 feet or more), was built in 1968 and 1969 under the 1949 Philadelphia Building Code. It was constructed of a steel I-beam frame with concrete-over-metal-pan floors, and its curtain wall consisted of granite slabs, set in concrete panels, and glass. Horizontal structural members were protected with sprayed-on cementitious fire-resistive material and had a two-hour rating, as per code; vertical members were encased in plaster and gypsum and had a four-hour rating, exceeding the three-hour code requirement. (Philadelphia Fire Commissioner Roger L. Ulshafer was later to comment that vertical-member protection was a major factor in preventing a total collapse of upper floors.) Building dimensions are 223 feet by 94 feet, providing 16,700 square feet of rentable space plus 4,000 square feet of core area for a total of 20,700 square feet per floor. Building height is 491 feet from ground to roof. There is a helistop on the roof, with two landing pads.

The building’s alarm system is comprised of manual pull stations and smoke and heat detectors tied in to the annunciator panel at the lobby control post and to a central monitoring agency. The three below-grade levels, as per city code, are protected with automatic sprinklers. Floors 30, 31, 34, and 35 also are fully sprinklered. The sprinkler systems are connected to the standpipe system. The building is scheduled for complete automatic sprinkler retrofit by 1993.

There are three stairways—east, west, and center. They are not smokeproof fire towers. These and other vertical shafts have a two-hour fire rating. As per a variance granted by the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections (building department), two out of even three interior stairway doors were allowed to be locked to prevent reentry, with the reentry points at every third floor marked by signs. However, firefighters operating within the building report that stairwell doors did not follow this pattern at the time of the fire. Floors were numbered, but stair towers were not identified either by letter or number.

Both the west and center stair shafts are equipped with a single sixinch standpipe riser; the east stair shaft has no standpipe riser. The Class I standpipe system was converted from dry to wet when automatic sprinklers were installed on the various upper floors.

Two 750-gpm fire pumps, one located in the basement and the other on the 12th floor, served the fire department standpipe system. The fire pump in the basement served floors 1 through 12, and the pump in the mechanical room on the 12th floor boosted pressure in the standpipes for floors 13 through 38 in both the west and center towers.

Pressure-regulating valves became part of the standpipe hose connections on floors 13 through 25 when the system was converted from dry to wet. Standpipe hose connections at the mezzanine (first-floor) level had pin-type pressure-reducing devices, as did floors 26 through 30. Floors 2 through 12 and 31 through 38 had standard, “nonregulated” supply valves. (See “Standpipes,” page 71.) The field-adjustable pressure-regulating valves on floors 13 through 25 had not been properly calibrated by the installation contractor (by human error or neglect, each had been calibrated to produce between 40 and 50 psi at the nozzle tip), and proper calibration had not been ensured by the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections, as was its responsibility; furthermore, the fire department did not have an operational familiarity with the pressure-restricting devices at One Meridian Plaza. These factors were to have a major role in the outcome of the fire.

Primary and secondary electrical power lines shared a common utility shaft in the core area. The emergency power generator was located on the 12th floor. There was no redundancy in emergency power lines.

Approximately 2,500 people worked in the building. Tenants included law offices and brokerage, banking, and accounting firms. Two of the tenant spaces contained open interior access stairs between floors. In general, fire loading on all the floors was heavy—heavy wood paneling, heavy wood furniture, and an abundance of office machinery. Excluding enclosed offices around the perimeter of the building interior, many tenant areas were not compartmentized with fire-rated, floor-to-ceiling partitions (open office plan). This was true of the 22nd floor, the area of fire origin.

Three people—security/maintenance personnel—were in the building at the time of the fire.

DELAYED ALARM

Shortly after 8 p.m., a smoke detector activated on the 22nd floor. The signal was sent both internally to the security desk and externally to the central station alarm company. Instead of notifying the fire department, the alarm company called building personnel. An individual from lobby control rode the elevator to the 22nd floor to investigate. When the doors opened, the employee was hit with extreme heat and smoke; he buckled to his knees. He was unable to reach up through the heat to the control panel to bring the elevator down. Fortunately, he communicated with a second employee at lobby control via portable radio and since elevator recall from the lobby is possible in the Meridian building, he was brought back down. The third employee took the stairs from the 30th floor and met with the other two employees. They called the alarm company, which finally notified the fire department. Precious time was wasted. The fire had been burning for at least 20 minutes. The initial alarm to the dispatch center was received at 8:27 p.m. from a caller on the street who reported smoke rising out of the building. Four engines, two ladders, and two chiefs responded on the firstalarm assignment.

RESPONSE

The officer of the first-arriving engine reported heavy smoke venting out of broken windows on the 22nd floor. Battalion Chief George Yaeger arrived and immediately requested a second alarm. He proceeded to the lobby and met with building security personnel, from whom he confirmed that all occupants were accounted for, the building’s HVAC systems had been shut down, and all but one bank of elevators, serving floors one through 11, had been removed from service. Yaeger established a command post in the lobby and reviewed the vital building information sheet required of all target hazards and large commercial structures in the city.

Glass and debris smashed down around the engine companies as they pressurized the standpipe system. A battalion aide worked with police to establish a safety zone and control vehicle and pedestrian traffic. All department apparatus not engaged in water supply were staged outside the safety zone.

Yaeger directed several companies under the command of Battalion Chief Mike Kukowski to initiate fire attack. They took the elevator to the 11th floor and walked to 22 through the west stair tower. The locked door in the stairwell was warped and blistering. Heavy fire was seen through the door’s wire-glass window. Members stretched a 1-Vi-inch handline from a gated wye connected to the 2’/cinch standpipe outlet two floors below, broke the wire-glass window, and played it through the window to keep fire away from the door while members forced entry, which took 20 minutes because the door was so deformed from the heat. Kukowski initiated command and control in that sector from the stairwell landing, using a grease pencil on the wall to track units during the initial phase of operations.

ONE MERIDIAN PLAZA 22nd FLOOR

Note: Perimeter office partitions extended from floor to drop ceiling. Center area office spaces were modular, half-height partitions. Access stairs connected 21st and 22nd floors. Offices contained heavy wood paneling and heavy wood furniture. Stairways were enclosed, without atmospheric break, exposing stairwells to heavy heat and smoke during fire attack.

Kukowski reported the heavy volume of fire on the 22nd floor and requested additional personnel for operations on the fire floor and the floor above. Deputy Chief James Brady assumed command of the incident and quickly called for a third-alarm assignment. He designated a logistics officer and put arriving second-alarm units on standby in the lobby while the building engineer attempted to make other elevators operational. The building’s elevator keys were secured from a room off the lobby (keys for fireman service are different for each high-rise building in Philadelphia). A firefighter was stationed by the elevator to prevent anyone from using the center bank—this was a blind shaft that led directly to the 22nd floor.

At that moment, primary and emergency power in the building failed and the building was plunged into total darkness. Brady ordered secondalarm units up the center tower to attack the fire from that position.

Meanwhile, Kukowski was attempting to establish a tactical command post on the floor below the fire. Teams forced entry into the area and encountered heat. An open convenience stair connected the 21st and 22 nd floors. Fire had dropped down in the stairwell and had communicated to the 21st-floor ceiling. From the stairway vantage point, heavy fire on the floor above was plainly visible. Members stretched a line from the west stair tower standpipe connection on the 20th floor and extinguished fire in the ceiling area, then attacked the fire in the convenience stairwell. Stream quality was poor and water pressure was low; even so, fire in that area eventually was knocked down. Kukowski ordered firefighters to establish a personnel and equipment staging area on the 20th floor. Eventually tactical command was moved to that floor as well.

“We were in a go-get-it mood in the building. The systems we were relying on in the building to work, we found out they weren’t working in our favor—they were working against us.”—Battalion Chief Pat Campanero

(Photos by Frank Saia.)

LOW WATER PRESSURE

Firefighters in the west stair tower continually were driven back in their attempts to advance on the fire with 1 3/4-inch handlines. They reported very little pressure in the lines. Nozzles, hoses, and the standpipe gate valve were checked and rechecked. Members checked for kinks in the lines and made certain that the standpipe valve was fully open—to no avail. One of the newly arriving units was ordered to check all standpipe outlets on the way up the stairs. All were shut.

Firefighters in the center tower also reported difficulties and delay in forcing entry and reported similar lack of pressure on the fire floor. They, too, were driven back into the stairwell.

IC Brady ordered engineers at the pumpers to increase pressure into the system. This had no effect on streams operating above. Kukowski reemphasized the need for additional personnel and spare air cylinders. The fourth alarm was requested, followed by the fifth minutes later. Firefighters made another attack from the west stair tower. With hose streams reaching only 20 feet, members were able to advance 15 feet before being driven back into the stairwell.

Realizing that the fire could not be extinguished at this time with a direct attack strategy. Kukowski decided to flank the fire with lines from the west stair tower and the interior convenience stairway from the 21st floor until help—personnel and water— arrived. The heat was so intense on advancing crews that another hoseline was used to cool the members so they could maintain their positions. Advancement was virtually impossible.

Standpipe pressure at the base of the system was 250 psi, but hose valves on the 20th floor were supplying only between 40 and 50 psi at the nozzle tip. Command directed firefighters to bypass the 12th-floor fire pump by connecting to the 13th-floor hose outlet from supply lines laid from the 1lth-floor hose outlet. This was unsuccessful. Firefighters also attempted to remove valves off the 20th floor standpipe outlet with a pipe wrench. This, too, was unsuccessful.

(Photos by Frank Saia.)

(Photo by Joe Hoffman.)

The fire now was rapidly consuming all combustible contents on the 22nd floor and extending to the 23rd, predominantly via autoexposure through the curtain wall and conduction through the floor, though fire did travel through the compromised utility shaft and interstitial spaces. (Autoexposure was the predominant means of rapid fire spread throughout the incident. Extension through elevator shafts, poke throughs, HVAC ducts, and utility shafts was not a major problem.) A reconnaissance of the 23rd floor by Chief Robert McBrearty and an engine company indicated a heavy heat and smoke condition, with near-zero visibility. They removed a piece of carpet from the floor: The rubber backing already had melted and the nailing strips were glowing red. Realizing that one poorquality hose stream would have no effect on the fire, McBrearty and his team backed out to join teams operating on the floor below.

Throughout the first few hours of operations, there was to be a constant call for additional water pressure.

EXPANDING CONTROL

Commissioner Ulshafer responded as per SOP on the third alarm and assumed command. Immediately he requested engineers familiar with the building’s systems—none were on hand. He acquired a set of blueprints. With all systems down in the building, he and chief officers implemented a variety of measures to compensate for the severe operational and logistical difficulties:

“The farther I went, the hotter it got. NA/hen I first entered, my feet were slipping. The rubber backing on the rugs was melting. I removed a piece of the rug. It was attached to wood stripping. The wood was glowing red.”— Battalion Chief Robert McBrearty, upon reconnaissance of the 23rd floor during attack operations on the 22nd floor

- Members gained access to exposure #2 —the 2 Mellon Bank Center, a 30-story office building adjacent to the fire building. They located what previously had been access points between the two structures, broke through the wall at the 10th floor, and interconnected the two standpipe systems with three-inch hose stretches.

- Four pumpers supplied each standpipe system from 3 1/2-inch hose to ensure a continuous water supply

- in case of mechanical breakdown.

- A logistics operations post was established on the 20th floor.

- Safety officers were designated for both interior and exterior operations.

- The department’s air vehicle unit extended its remote 400-foot air line via the exterior of the building to a refilling station positioned on the 20th floor.

- A sixth alarm was called, and an air-bottle/equipment shuttle was established because of the large number of personnel now operating and great demand for air. Two members were stationed at every other floor. Elevators in the Mellon Building were used to transport air bottles and equipment 10 floors up to and down from the crossover point created between the two buildings. This took some of the stress off the shuttle team, but unfortunately it was to be short-lived.

- First-aid sectors were established on the 20th floor, in the lobby, and remote from the building at ground

- level. Rest and rehabilitation was established on the 20th floor.

- Medic units were set up in the lobby area and were prepared to be dispatched to any portion of the fire building or fireground.

- A staging area for medical transportation vehicles was established.

- Accountability and control of personnel were tightened. There was a constant demand for fresh manpower. Status sheets were used to track companies operating in the stair towers, those in rehab, and those available. Relief of operating units occurred after 15-minute intervals. Companies that had lost personnel to injury or additional rehabilitation were combined with other short-staffed companies to create full units.

- Command was apprised of the helistop on the roof should an alternative method to and from the roof be necessary.

- Communications center personnel recalled off-duty manpower. Reserve engines, fully equipped at several locations throughout the city, were placed into service. Staff cars and vans delivered off-duty personnel wherever they were needed to man apparatus. Several off-duty chiefs worked with dispatchers to coordinate the effort. Several pumpers sitting idly at the fire scene were brought to strategic locations to cover fire calls.

- Telephone communications also went down when the building lost power. Dispatchers established contact with the communications van and the lobby command post through cellular telephones. This expedited communications and did not tie up the radio with lengthy messages.

“We kept up with filling SCBA cylinders at the staging area. At one time we had more than 100 full cylinders and only 25 empties.”—Logistics Officer Captain William Rice, acting battalion chief

ONE MERIDIAN PLAZA 20th FLOOR LOGISTICS AND STAGING

The constant search for competent building engineers continued.

THE CONTINUING FIREFIGHT

For all the effort expended in interconnecting standpipe systems, the water supply situation did not improve: Command, though aware that the problem was in the system’s pressure-regulating valves, was unable to correct the water supply problem. With the difficulties experienced in supplying 1 3/4-inch attack lines, switching to 2 1/2-inch or 3-inch would have been pointless.

Companies were reporting that they could advance only a short distance before they felt the heat come from behind them—in a “donut” effect-even though the building was not a center-core type of structure. The fact that hose streams by that time could easily be coordinated so as not to oppose each other (because the west and center stair towers led to the tenant space in parallel directions) was of little consolation as some streams were reaching only six feet. With fire rolling back at firefighters almost instantaneously after they had darkened down the immediate area, no progress was made. Eventually, fire consumed the available fuel load on the 22nd floor.

Attack operations moved to the 23rd floor in a state of catch-up. At this point, firefighters were unable to attack simultaneously from different floors because all lines and personnel were needed on the same floor if they had any hope of making a dent in the fire.

Problems continued to mount: Falling glass continually cut hoselines supplying the standpipes, and chunks of the eight-ton granite/concrete exterior panels also were falling down to the street.

“Every time we replaced a section of hose feeding the standpipe, it would get punctured.”—Captain James McGarrigle, acting battalion chief

The interconnection of standpipes between the two adjacent buildings for additional water was completed but was ineffective because of the pressure-regulating valves.

The 400-foot air line supplying the remote filling station on the 20th floor was severed by falling glass, and a spare air line had to be pieced together and pulled back upstairs by rope.

“Whatever we did on the 22nd floor, I knew we were going to do on the 23rd floor and possibly the 24th, which was asking the impossible.”—Battalion Chief Pat Campanero

Shortly after the air-bottle/equipment shuttle was established, command received a report from building personnel at the scene that water running down the stair shafts would soon affect the transformer in the basement of the fire building—the transformer also supplied electricity to the Mellon Building—and that power would be lost in that building as well. Firefighters set up submersible pumps in the basement to overcome the problem, but to no avail. Power in the Mellon Building was shut down.

Fire was now overlapping the curtain wall into the 24th floor. Chiefs changing air cylinders continually discussed strategy and whatever tactical options they could try.

Conditions in the stair towers were worsening. The towers were constructed without an atmospheric break or outside balcony; a single door separated the stairs from the fire floor. This allowed considerable heat and smoke to contaminate the stairwell, as firefighters had to open the doors to launch an attack. With stairwell integrity in jeopardy, three members of Engine 11 were ordered to the roof via the center stairs to open the bulkhead door and vent the stairwell. They were then to proceed across the roof and open the doors to the other stair shafts.

“WE’RE RUNNING OUT OF AIR”

Some time later, Captain David Holcombe of Engine 11, a 28-year veteran of the Philadelphia Fire Department, calmly reported over the command channel that his team was experiencing a problem on the 30th floor en route to the top of the stair tower. They had exited the stair tower and wanted to break a window but didn’t know what side of the building they were on. Ulshafer ordered a fireground announcement for all personnel to stay clear of the perimeter of the building until the window was broken. Fie radioed Engine 11 that if they had a problem in the center tower, they would be directed to one of the other towers. Smoke was so heavy at this time that units on the ground were unable to determine which window was broken. Firefighter Phyllis McAllister from Engine 11 radioed that the team was in real trouble now. The captain was down and they needed help.

Ulshafer assigned Deputy Chief Matthew McCrory the task of assembling a search and rescue team to proceed immediately up the center tower to the 30th floor. Then he ordered Acting Chief James McGarriglc and three firefighters to prepare for a helicopter lift to the roof, from where they were to accomplish three objectives: vent the stair towers, assist in the rescue of Engine 11 if possible, and assist any injured to the roof for removal by helicopter. Calls for helicopters were placed to the nearby University of Pennsylvania Hospital trauma center and to the Coast Guard station in Cape May, New Jersey, 75 miles away.

Command received another transmission from Engine 11: “Help us, we’re in trouble. We’re running out of air.”

The search team, now at the center stair tower, 22nd floor, faced the prospect of an untenable, extremely heavy heat and black smoke condition in the stair towers above the fire. McCrory advised command that doors to the fire floors would have to be closed before they could proceed to the 30th floor and advised McGarrigle, awaiting helicopter transport, to open the door to the center stair tower first.

The trauma center helicopter arrived after a one-minute flight and delivered the vent team to the roof (one firefighter was left below because there was too much weight in the helicopter). Firefighters were accompanied by a nurse and a paramedic. Initial survey of the area indicated two helicopter landing pads on a flat roof; no ventilating system components, bulkheads, or doors were visible. There were no clear indications of stairshaft openings. Building blueprints at the command post did not clarify the situation.

Two narrow sets of steps on either side of the helipad, similar to an exterior fire escape, led to the 38th floor. The team located a door on the west side. When they opened it, heavy smoke pushed out. Using a rope as a guide, two members entered. They encountered a heavy smoke condition in the 38th-floor mechanical room. They were ordered back up to the roof. They propped open all the doors they found on the way there.

RESCUE EFFORTS

In the center stair tower, McCrory reported that heat and smoke were beginning to lift. Units operating in the center stair tower were withdrawn to staging except for one engine company, on standby in case fire breached the stairwell door after the rescue team went above. Eight firefighters ascended the stairway to search for Engine 11. Each firefighter had an extra air cylinder. The tower was fairly clear until they opened the door to the 30th floor.

“The 30th floor was banked down with smoke. We proceeded to search, which was extremely difficult because of all the cubicles. No hallway seemed to lead anywhere. They all led into other rooms and hallways.”—Lieutenant Michael Vaeger, when describing an initial attempt to rescue Engine 11.

The smoke was banked down, hindering the search through the mazelike occupancy. Firefighters inverted selected pieces of furniture to mark areas that had already been searched. Others worked the perimeter, looking for the window that was supposed to have been broken out. The search on floors 30 and 31 proved negative. After switching air cylinders, the team searched floors 32 and 33—again, negative.

With their air now running low and being so close to the roof level, the teams decided to use the roof for egress. Hie tower was smoky but passable. It led to a large mechanical room with a 24-foot-high ceiling, filled with heavy equipment, with catwalks and wall ladders that seemed to lead nowhere. The firefighters closed the door to the stair tower. Six air cylinders were empty; two had only quarter-tanks left. The firefighters searched for an exit to the roof and were unsuccessful, and contacted McGarrigle, who was on the roof. They were starting to experience trouble.

(Photos by John Axford.)

Accompanied by a firefighter, McGarrigle descended that stairway and encountered a locked electrical closet. They returned to the roof and descended the stairs on the other side, entering one door and then yet another before finally entering the mechanical room. They located the trapped firefighters and led them up to the roof, from where they were brought via helicopter to the ground.

McCrory called for additional manpower to effect a thorough search of the upper floors through the east stair tower. Primary search was completed on floors 34 through 38, and secondary search was performed from 38 to 29. These proved negative. Meanwhile, McCrory, monitoring rescue operations, descended the center stair tower. Conditions again were deteriorating badly—the doors to the fire floors had been opened again for attack operations. He made his way back to staging and radioed Chief Brady in the lobby, requesting that he put the helicopter into operation to search for a window that Engine 11 might have knocked out.

CREATING A STANDPIPE SYSTEM

By now the fire had control of the 23rd floor and was gaining headway on the 24th. The commissioner ordered all rescue teams below the fire. He transmitted the eighth alarm (the seventh was for additional personnel to stretch large-diameter hoselines). There was a report of fire on the roof of an eight-story building on the south side of the fire building. Embers had dropped down and ignited its roof. Two units were able to control its extension.

Ulshafer called the ninth alarm and placed units on the 30th and 35th floors of the 43-story building across a narrow street on the exposure #4 (west) side. From there they operated lightweight deluge guns in an attempt to control some of the autoexposure on the west side of the fire building.

With interior attack on the fire ineffective because hose streams had virtually no horizontal reach and no penetrating power—in some cases Rockwood Navy-style nozzles were substituted for automatic nozzles in an effort to maximize what little pressure they had (still this was insufficient)—Ulshafer decided to stretch five-inch lightweight hoselines up the stair towers to get additional water and called the 10th and 11th alarms. Firefighters in effect would be creating their own standpipe system, supplied by additional pumpers at the scene. It was now almost four hours into the operation.

Top photo by Joe Hoffman

bottom photo by John Axford.

“They had four 1 3/4-inch handlines in one doorway and didn’t advance one foot in 20 minutes.”—Deputy Commissioner Chris Schweitzer, describing conditions on the 24th floor

A team of doctors was requested to supplement paramedics in the forward first-aid area on the 20th floor because firefighters were taking heavy punishment from the heat and smoke. The structure itself was showing the effects of the fire: Companies operating in the stairways saw and heard significant cracking and shifting in the tower walls.

Approximately 30 firefighters brought LDH up the stair towers in sections, beginning with the center tower, while members covered supply lines on the street with plywood trenching sheets from a soon-to-be-inservice rescue truck. A firefighter who was replacing damaged hose suffered a compound fracture of his arm when he was struck by falling glass.

“No one in the building knew how to overcome the PRVs. Nobody knew that a rod existed, and it took them almost five hours to get somebody in who did know…. Even when this guy came, we thought he would hydraulically calculate based on whatever their scale weight equated to…. When he finished, we asked him what the conversion factor was, how he did it. He said, T just kept putting that rod in there until that line felt hard and your guys said they had enough pressure.’ By that time we also had four floors of fire instead of one so that playing catch-up was very, very significant.” — Commissioner Roger Ulshafer

It took an hour and 20 minutes for firefighters to complete the first makeshift standpipe system. The fiveinch supply lines were connected to a five-outlet manifold that fed threeinch lines, which in turn fed portable deck guns and attack handlines. With good streams in place, firefighters attacked the 23rdand 24th-floor fire with some confidence. Later the west tower “standpipe” was in place as well. (Firefighters also stretched LDH in the east tower as far as the 17th floor before operations were abandoned.) Progress was reported on the 23rd floor, but it was not enough to prevent further extension into the floor above.

Fire on the 24th floor became very intense, due to particularly heavy fire loading in that area. In retrospect, the 24th floor would become a turning point in the operation. Even with adequate manpower and water pressure, units made no headway. From one stair tower, firefighters operated several deck guns into one doorway and still were unable to advance even one foot into the fire floor. From another, four l Veinch handlines had no effect on the fire. Modular cubicles in the center of the tenant spaces were shielding the fire from hose streams. To make matters worse, another open convenience stairway connected the 24th and 25th floors— an easy channel for vertical spread. Deluge guns were positioned on several floors in an attempt to get ahead of the fire. Nevertheless, the fire was extending rapidly: It had a four-hour head start.

Nearly five hours into the firefight, after continuous attempts by Ulshafer to produce an engineer familiar with the building’s standpipe system, one responded to the scene. He informed command that the water pressure problems they were experiencing stemmed from improperly calibrated pressure-regulating valves at the standpipe connections on the fire floors. He adjusted the valves with a special rod designed for that particular type of valve, so that adequate pressure was available—not by hydraulic calculations but by turning the valve rod until the line felt hard and firefighters signaled that they had enough pressure. However, as with the makeshift standpipe system, even with adequate water the well-advanced fire was taking its toll on the firefighters and the building. The commissioner reported that fire was now on the 25th and 26th floors.

ENGINE 11 FOUND

Through the intense smoke pouringout of the building, the helicopter discovered a partially broken window at the southeast quadrant, or rear corner of the 28th floor. Chief McCrory assembled a rescue team led by Battalion Chief Walter Cuniff and sent them to search the 28th floor. They proceeded up the east stair tower. (While ascending the stairs, fire from a closet area broke through the stair tower concrete block wall and pushed heavy black smoke. Firefighters had to knock down the fire before going past it and upstairs.) Cuniff checked floor conditions on the way up to 28: Each time they opened a door, heavy smoke pushed out. Cuniff ordered his team back down to staging on the 20th floor to assemble a larger crew and get fresh air bottles.

There was a medium-to-heavy smoke condition on the 28th floor that didn’t lift. Firefighters with flashlights were positioned every 20 to 30 feet, forming a chain. Voice communication could be maintained and firefighters could track their way out. Cuniff crawled down several corridors. Additional firefighters marked the escape route. Cuniff could feel cool air and made his way toward it.

He found the three fallen firefighters of Engine 11—Holcombe, McAllister, and Firefighter James Chappell—near the partially broken window. He called for medical assistance immediately, but smoke conditions were not conducive to medical treatment. Cuniff notified the doctors on the 20th floor that they were bringing down the missing firefighters. Attempts to revive them were futile—they were discovered hours after their last radio transmission.

“Fresh troops: That was a guy that walked 22 floors carrying his SCBA in full bunker gear, packed up, grabbed a line, and went another two floors to go fight the fire.” —Deputy Commissioner Chris Schweitzer

EVACUATION

Commissioner Ulshafer was concerned about the integrity of the stair towers from the smoke and heat. Now he was even more concerned about structural damage. There was continual movement and cracking in all three towers. In one stair tower, what had been a two-inch crack in the concrete wall had grown to a fistsized opening. Floors had moved as much as three feet. I-beam flanges were cracked. Fire-resistive material on the beams in the stairways had fallen off, and the now-unprotected members were twisting, moving, and starting to elongate. Main structural elements were beginning to fail. Ulshafer called a structural engineer to the scene.

Meanwhile, members sent to operate on the 25th floor encountered superheated gas and smoke. Deputy Commissioner Chris Schweitzer, who was now in command of tactical operations, reported that the smoke was down to the floor and that combustion by-products were blowing out under pressure into the stair towers— in Schweitzer’s words, “the kind of smoke you pay attention to.”

Schweitzer strongly advised Ulshafer not to place firefighters on the 25th floor. Almost all companies were engaged in the firelight on the 24th floor. One line and two companies above that would be ineffective and unsafe. Hours into the attack on 24, firefighters were no further along than when they began. The fire was racing ahead of the firefighters, floor by floor. The firstand second-alarm companies still operating were directed to an out-of-service area on the 19th floor under strict orders not to go back into service without Schweitzer’s okay.

A structural engineer arrived on the scene and investigated the building interior, going up as far as the 24th floor. He noted that the structural problems were substantial. He believed that, particularly with freeburning fire on the 25th and 26th floors, internal collapse was a possibility. Schweitzer conferred with Ulshafer in the lobby to discuss the situation at hand. They ordered firefighters on the fire floors to shut down handlines but keep deck guns operating, then moved all firefighters to the 15th floor.

(Photo by Tony Greco.)

(Photo by Michael Molly.)

(Photo by Joe Hoffman.)

With the potential for even greater vertical fire spread and structural collapse and with safety of personnel the top priority, Ulshafer decided to evacuate all firefighters from the building. This order was given at approximately 7 a.m. on February 24, almost 11 hours after operations began.

The only hope was that automatic sprinklers on the 30th and 31st floors would extinguish the fire. Department efforts now centered on maintaining supply lines into the combination sprinkler and standpipe system, protecting exposures, and moving all nonessential personnel and vehicles to an area that would be unaffected by a collapse into the street.

Three lines were set up from the 25th floor of the #2 (eastern) exposure, the Mellon Building. Its upper four floors had smaller dimensions, creating a separation between the two buildings. Across the narrow street on the exposure #4 (western) side, deluge streams were kept in operation. The command post was repositioned to a location at surface level.

Firefighters watched as One Meridian Plaza free-burned, extending to the 30th floor. Nine sprinkler heads on that floor activated—two in the interior of the floor and seven along the perimeter. They controlled and extinguished the fire. Commissioner Ulshafer declared the fire under control at 3 p m. that afternoon.

(Photo by John Christmas.)

POSTFIRE

The building was left to cool for a day before firefighters reentered the building. Floors 22 through 29 were totally destroyed.

The Office of the Fire Marshal of the City of Philadelphia, assisted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms’ national investigative response team, determined the cause of the fire to be spontaneous heating resulting in the ignition of cotton rags containing linseed oil. Workers had been refinishing the woodwork on the 22nd floor. A number of materials in the room —including naptha, paint thinner, and assorted polishes and waxes—contributed to the rapid fire spread. Fire penetrated the suspended ceiling and traveled rapidly through the plenum to a hole in the utility shaft off the electrical room that had never been repaired. The primary and secondary feeds for the building’s electrical systems were in this same utility shaft. Once the fire took out the primary wiring, the secondary wiring was right next to it. All power was lost at that moment.

At the height of the fire, 51 of the city’s 61 engine companies were operating at the scene as well as 11 truck companies, 21 chief officers, and numerous medical and support vehicles. Citywide response never dropped below 20 pumpers because of recall personnel manning reserve rigs.

Soon after the fire, members attended a critical incident stress debriefing.

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

- At any structure fire, inadequate water supply will at best severely limit fire suppression capability. At a high-rise fire, that deficiency will be magnified a thousandfold. Just as the fire department must understand a city’s fixed water supply, so it must be intimately familiar, theoretically and practically, with fixed vertical water systems, their components, and related systems. Lack of information on pressure-regulating valves on the standpipe connections at One Meridian Plaza was critical to the department’s ability to control the fire in the earlier stages of growth.

— If not already established, the fire department should pursue a regular inspection and testing program for every standpipe system —including valves and appliances. A competent, professional fire protection engineering firm should be contracted for this purpose.

— Installers and maintainers of fire protection systems installations—including PRVs—must be made to understand the importance of that responsibility. Penalties for negligence must drive the point home.

— If review and approval of fire protection system installations are not official responsibilities of the fire department, fire officials should strongly request that they be placed under fire department jurisdiction. More than any other agency, the fire department has a vested interest in these systems and their components. The Philadelphia Fire Department has strongly requested such action; currently, it does not have power of enforcement in overseeing these installations.

—The review and approval agency must keep the fire department abreast of new or unusual fire protection system installations and components.

— All fire departments must preplan target hazards and their fire protection systems and educate and train members in their operation. Merely noting on a preplan that a specific installation exists does not ensure operational preparedness. Provide complete details on how to operate specific installations on updated preplans.

Following the fire, the Philadelphia Fire Department surveyed all highrise buildings in the city to determine what types of pressure-regulating and pressure-reducing valves are being used and how they operate. This survey has yielded some interesting results, among them: PRVs were found on dry standpipe systems; most PRVs in the city are field-adjustable; a significant number of building maintenance personnel were not aware of PRVs in their buildings or even of what they are.

- The One Meridian Plaza fire provided the fire community and the world with another dramatic testimony to the value of automatic sprinklers. Without sprinklers, nine floors were completely destroyed. With sprinklers on the 30th floor, a freeburning, out-of-control fire was extinguished— with nine sprinkler heads. Philadelphia firefighters stretched themselves to the limits of pain and endurance and, given the odds stacked against them, could not do what those few sprinkler heads did.

No high-rise building, regardless of when it was built, should be without complete automatic sprinkler protection. The same is true for any target hazard with a significant fire load/life hazard. The risks to life and property are simply too great. The fire service must reinforce this lesson at every available opportunity.

- Autoexposure through the curtain wall was the primary means of rapid fire spread at this incident, as also has been the case at other recent high-rise fires. The fire service should encourage model code-making bodies to reevaluate provisions that permit building construction whereby rapid exterior vertical fire extension from floor to floor makes fire containment a nightmare.

- Fire operations were significantly hindered by the absence of building personnel who knew the building’s systems and could provide the incident commander with desperately needed information. A fire safety director must be a part of the fire protection system. The building should “speak” to the incident commander through competent, welltrained building personnel —particularly the fire safety director. (See “The Role of the Fire SafetyDirector” on page 67.)

- All building personnel must be educated in the importance of notifying the fire department immediately upon receipt of a fire alarm in a highrise building. The Philadelphia Fire

- Department is seeking to change the consequences of failing to report a fire from a misdemeanor to a criminal offense.

- Central stations must immediately retransmit alarms of fire to the public fire service communications center as required by Sec. 1-10.2.1 of NFPA 71. Fire departments should consider revoking approval of central stations that do not meet the requirements of NFPA 71. Investigation of the actions taken by the central station for One Meridian Plaza is ongoing.

- A placard system within high-rise stairwells at each standpipe connection for pressure-regulating valves is recommended. The placard should identify the valve and the nozzle tip pressure that can be expected from it.

- Fire departments should seek to amend codes that allow primary and secondary electrical power lines to exist in the same utility shaft—as was the case at One Meridian Plaza— unless there is redundancy in the system at a remote location. Primary and emergency feed lines should be remote from each other. Once fire penetrated the utility shaft, it was a matter of seconds before fire took out all power in the building. Personnel were unable to restore power during the entire firelight.

- Engineers/utility companies must account for the possibility of water collecting in basement areas, threatening damage to building system components there. The air-bottle/ equipment shuttle from the elevators in the attached exposure building had to be abandoned because the shared transformer in the basement of One Meridian Plaza was under water.

- Access stairways between floors were a factor in this fire and reiterated that they are as convenient for the fire as they are for the tenant. Their use should be limited solely to fully sprinklered buildings. In most circumstances, the possibility of rapid fire spread up (or down) these unprotected vertical channels far outweighs any benefits derived from their tactical use during fire attack.

- A rule of thumb or SOP of many departments is to request a second alarm on arrival at a working fire in a high-rise building. Departments should consider the benefits of upgrading to a third alarm on arrival for working high-rise fires. Even with the best conditions and the smallest fire, the time factor and the logistical and operational demands are great. Three alarms of companies would be utilized.

- Updated layouts of tenant spaces and mechanical rooms must be madeavailable to the incident commander and operations commanders immediately. This task should be the responsibility of building safety/security/fire safety personnel. Engineering blueprints did not provide the incident commanders at One Meridian Plaza with certain required information. Firefighters attacking the fire and searching upper floors were hindered by not having a general idea of what to expect in the tenant spaces. The unusual and confusing layout of stair tower doors leading to a large mechanical room with maze-like catwalks and subdivisions was problematic to stair tower ventilation and could have added to the tragic personnel losses experienced at this fire.

- As no two incidents are the same, the creativity of chief officers may play a significant role in operations. Opening an access point between the fire building and the attached exposure for standpipe interconnection and elevator shuttle, creating a standpipe system with large-diameter hoselines, and using a helicopter in suppression and search operations were examples of this creativity at the One Meridian Plaza fire.

- The incident command system has proven its value in both large and small incidents, and worked well at One Meridian Plaza. Remember, however, that it is not a rigid system Departments must adapt the system to tlie specific incident. This was accomplished at Meridian: Positions were added as the incident progressed, sector officers were doubled up, etc.

- If at all possible, at high-rise incidents an evacuation stairway should be designated and its integrity maintained. This stairway should provide egress for firefighters trapped on upper floors and access for search, rescue, and logistical operations. Rescueoperations should not have to be delayed until attack operations are discontinued.

- In the Meridian Plaza incident, the integrity of the east stair tower was maintained through most of the operation and was used for search and rescue, air-bottle shuttle, and movement of incoming personnel.

- Stair towers in all high-rise buildings must be adequately identified. Smoke in the stairwells, darkness, and different floor layouts can disorient firefighters.

- Two companies should be assigned to each line so that attack is uninterrupted during rotation of units.

- At high-rise fires, where a multitude of tasks must be performed simultaneously, personnel accountability and control are essential. Personnel staging, rest and rehabilitation areas, and nearby medical areas are vital to firefighter safety in incidents of long duration. The fatigue factor makes rotation of all personnel, including chief officers, essential. Officers must temper the aggressiveness and overenthusiasm of units, especially in view of potential long-term operations. Rest periods must not be skipped unless deemed appropriate by chief officers.

- Loss of telephones at the lobby command post forced the extensive use of cellular phones at this incident. This took some of the traffic off the two fireground channels and also allowed officers to converse in relative privacy.

- Falling glass is a major threat to safety at a high-rise incident. Safetyzones must be established, maintained, and readjusted as necessary. Height of the fire floors and wind currents are determining factors.

- If possible, on dispatch identify what additional companies probably will be doing on arrival. This helps in the command function, helps to prepare incoming firefighters mentally for the tasks, and helps to ensure that they will have the equipment they need for the task.

- Firefighters must wear and use PASS devices at all fires. It is undetermined whether the three members of Engine 11 had turned on their units while operating above the fire. Operating PASS devices may help to speed the rescue—with benefits both to the trapped firefighters and to those searching for them.

- The use of safety ropes provides for safe and orderly search, evacuation, and retreat.

- A helicopter was used effectively at One Meridian Plaza for roof operations. Incident commanders at highrise incidents should consider early on in the incident how helicopters could be used to advantage, if necessary, and should contact appropriate agencies in advance to place available helicopter units on standby. Preplans should indicate which buildings in the jurisdiction are suitable for helicopter roof transport operations.

- The equipment arsenal for highrise firefighting must match anticipated worst-case scenarios. The Philadelphia Fire Department is including smooth-bore nozzles in each company’s high-rise pack.

- Recall of personnel was vital to the operation. Stations had to be covered and reserve apparatus manned. A system for call back of personnel is invaluable.

Special thanks to Commissioner Roger Ulshafer and members of the Philadelphia Fire Department for their cooperation and assistance in making this report possible.