The Dangers of Outside Venting

Strategy & Tactics

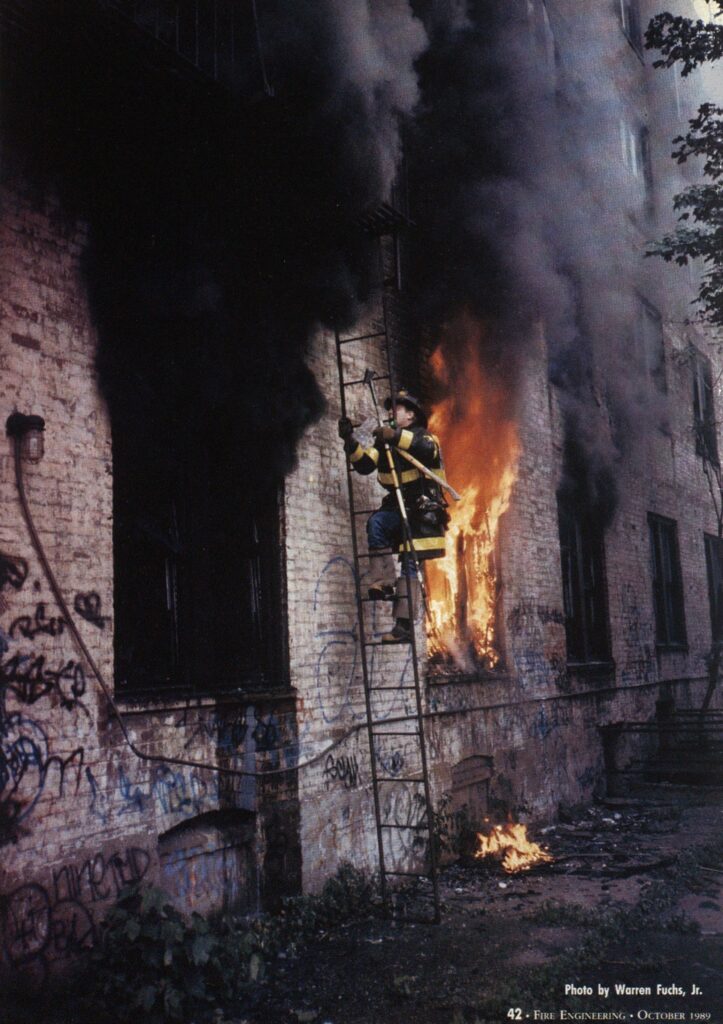

Photo by Worren Fuchs, Jr.

“VENT THE rear of the building!” the officer shouts to the firefighter. “10-4, Captain.”

The firefighter runs through the front yard of the burning 2 1/2-story frame house carrying a pike pole and halligan tool. An uncharged 1 3/4-inch hoseline is being stretched to the front entrance. There is no visible flame, but dark brown smoke pushes out of every opening into the early morning daylight hours. It pours downward out of the eaves of the gabled roof, heaves out the open attic window, and forces its way out of the top of the partly opened front doorway and cracks in the window frames.

Near the entrance in the front yard, a woman in nightclothes clutches a doll and gestures wildly. “My baby! My baby is still inside! Please save my baby!” The firefighter assigned to vent the rear of the building from the outside runs over to her. “Lady, where inside the house is your kid?” Her words rush out in short gasps: “He’s in the bedroom! My baby is sleeping in the bedroom!” Again the firefighter asks, “Where? Lady, where is the bedroom —first floor? Second floor? Front? Rear?” “He’s in the crib in the bedroom on the first floor,” she cries, “next to the kitchen. Please, I beg you, save my baby!”

The firefighter runs to the side of the house, pushes open a gate in a small fence enclosing a side yard, and heads for the back of the structure. Halfway there, out of the corner of his eye he sees a small, dark object running toward him: It’s a snarling dog. There’s no turning back. Running toward a higher fence in the rear yard, he pitches the tools over it, jumps up, grabs the top railing, and pulls himself over the fence. The dog leaps and snaps at his heels as he escapes.

Once in the backyard, the firefighter sizes up the building. There are two first-floor windows with smoke around the frames. The glass is stained dark brown, and condensed smoke is dripping down the inside glass panes. He sees flames flickering inside the room through the left window. Which window leads to the kid’s bedroom? the firefighter asks himself. I’ve got to get that kid! He hears shouts of “Start water!” coming from the front of the house.

The firefighter notices a kitchen exhaust fan next to the window on his left and concentrates his efforts on the other. Must be the bedroom. The window is old and sealed with paint; he can’t force it open. He grabs his pike pole and, standing to the side of the window, swings it at the top pane. Crash! Heavy smoke flows out of the top of the window, but no flame. Crash! He repeats the procedure for the bottom pane, then hooks the center wood frame with the pike pole and rips it out of the opening.

Dropping the pike pole and picking up the halligan, the firefighter looks around. He grabs a metal garbage can, turns it upside down, places it directly below the bedroom window, climbs up, dons his mask facepiece, and slides in over the bottom of the window sill.

Inside the smoke-filled room, the firefighter stays low. He sees flames through a partly opened door to another room. The smoke is stratified just above his head. He sees a stuffed chair, table, and wall in an outer room engulfed in flames. Crawling on the floor, the firefighter shuts the door partly, separating the bedroom he is about to search from the fire in the next room. He hears the hose stream crashing against the plaster walls outside the room. The hoseline is knocking down the fire; that’s good, he thinks. Smoke and heat inside the bedroom start to lift because of the open window.

Suddenly, the firefighter sees the crib. He feels the mattress and a small lump under the blankets. He picks up the child with both hands, quickly wrapping him in the blankets, and heads back to the window. The small body is motionless.

Laying the bundle down on the floor next to the window, the firefighter quickly climbs halfway out feetfirst. Picking up the baby, he jumps first to the garbage can and then to the ground.

Crash! Crash! Crash! Firefighters on the second floor are venting glass windows from the inside. Bending over to shield the small bundle with his back and shoulders, the firefighter runs away from the building out of the path of falling glass.

Down on one knee, he frantically pulls the tangled layers of blanket and sheets apart, trying to find the child’s face. He finally uncovers a small, sootcovered face with closed eyes. The child is not breathing.

Tilting the head back and holding him with two hands on his bended knee, the firefighter covers the child’s small mouth and nose with his mouth and puffs into his small chest. One and two and three! The firefighter feels movement in the blanket —knees and arms kicking and twisting. The baby begins to cry. “Thank God!” the firefighter says.

Standing up, he runs to the front of the house from the other side to avoid the dog. Hugging the bundle, he half kisses, half puffs air into the screaming baby’s face.

In the front yard, the mother and emergency medical personnel tug at the child in the firefighter’s arms. The chief, standing nearby, radios to the firefighters inside the burning building who are still frantically searching for the baby. “Urgent! Urgent! All hands inside the fire building. We found the missing baby. The baby is safe,” the chief says. “Take it easy. No unnecessary risk taking. Just concentrate on putting out that fire!”

QUESTION 1: Which of the following statements is true concerning the clangers firefighters assigned to outside venting face?

- There is danger of falling objects, glass, furniture, tools, and shingles.

- There is danger of flashover.

- There is danger of falling from ladders, porches, and fire escapes.

- There is danger of being trapped by fire.

- All of the above are dangers outside vent firefighters face.

QUESTION 2: Which statement is false regarding the duties of outside vent firefighters?

- They require knowledge of safe venting techniques.

- They require knowledge of safe search techniques.

- They require knowledge of safe portable ladder operation and fire escape climbing.

- The require know ledge of fire size-up techniques.

- They are similar at every fire.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 1: The cor rect answer is E. Choices A, B, C, and D are all correct statements.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 2: The false statement is E.

One of the most dangerous firefighting assignments at a fire is outside venting. How can that be? you might ask. Compared with some other firefighting jobs such as advancing an attack hoseline and searching above a fire, venting windows seems easy. The firefighter performing ventilation is outside of the burning building and all he has to do is break a few windows, right? Wrong! A closer look at outside venting shows that it requires knowledge, skill, and determination.

The firefighter assigned to vent the outside of the building must often work alone, sometimes at the rear or side of a burning building. If he is trapped or injured, no one will see and come to the rescue.

The duties of the outside vent firefighter are varied and dangerous. Just to get close to a window that needs to be vented, the firefighter may have to climb over a fence, fight off an attack dog, force open a lock on a gate, climb over or cut barbed wire, raise and climb a ladder, scramble up on a porch roof, and lower a counterbalance stairway or access ladder of a fire escape.

The following are some of the fireground dangers and safe operating techniques a firefighter assigned to outside venting should know about to increase his own safety.

DANGERS AROUND THE PERIMETER

Firefighters venting windows from outside a burning building have been killed and seriously injured by objects falling out of or collapsing off of the structure. These firefighters must realize that they are operating in one of the most dangerous areas of the fireground: the perimeter around the burning building. Firefighters inside the fire building are concerned with searching, extinguishing, and venting. They don’t always know the exact location of the firefighter venting from the outside because his position varies from fire to fire. As windows are vented from the inside, glass falls out. Hose streams extinguishing fire also blast windows outward. The outside venting firefighter must be aware of these dangers and try to avoid them while performing his assigned duties by positioning himself away from any possible direct path breaking glass may take.

Falling objects that often injure outside venting firefighters include broken window glass from inside venting, tools that slip from the hands of firefighters operating above, large smoldering furniture pushed out of the window at night after a quick fire knock-down, bricks or cap stones loosened by a hose stream striking a parapet wall or chimney, slate shingles on a sloping peaked roof heated by an attic fire, and even people who jump off of buildings to escape flames.

There are several operating precautions firefighters can take to avoid injury from falling objects during outside venting. Eye shields and a properly fitting helmet are two of them. Also, all new firefighters are warned in basic training school: “When you hear glass breaking, don’t look up.” That’s sound advice.

Size up the venting assignment from a distance, if possible, to avoid falling objects. Choose the window you want to vent, move in close, vent it, and back away from the structure. However, if the yard or alley is narrow and you can’t stay outside the collapse danger zone, stay very close to the building, hugging the wall. Objects falling from upper floors may be propelled several feet away from the building.

There are often areas around a building beneath which the outside vent firefighters may take refuge. A recessed doorway, a canopy over a door, a porch roof, a fire escape balcony, and a decorative overhang or cornice may all provide temporary protection against falling objects.

PORTABLE GROUND LADDERS

When a fire occurs on the upper floor of a twoor three-storv residence, the firefighter venting outside must place a ground ladder at the rear or side of the building in order to reach a window. He may have to place the ground ladder to the roof of a porch, to a one-story extension, or to the window itself. Outside venting firefighters climbing ground ladders can be injured in two ways: by placing the base of the ladder at a precarious angle (it slides out from under the climbing firefighter and befalls from the ladder) or by falling off the tip of the ladder because the window explodes outward into his face as he is about to vent it.

To ensure that the base of a ground ladder does not slide out from under you, place the ladder at a proper climbing angle. The base of the ladder must be an optimum distance away from the wall of the building. T here are many formulas for calculating this distance (ladder length -r 4, or ladder length 45 + 2). However, during a fire there is usually no time to calculate. Here’s the quickest and best way to determine if the ladder is placed at a sale angle: After raising the ladder, stand erect at the base of it with your boots against the beams of the ladder and your outstretched arms grasping the rungs at shoulder level. If you can do this, the ladder is at the proper climbing angle. If not, the ladder should be readjusted.

A ground ladder can still slip, especially if the base is resting on broken pieces of glass on a concrete patio or driveway, if the surface is icy or wet, or if the ladder base moves from the vibrations caused by climbing or operating near the ladder tip. In life-threatening situations, you may have to climb a ground ladder at an unsafe angle. If so, either tie the ladder to an immovable object, have another firefighter hold the ladder in place, or, if possible, quickly create a small hole or depression in the earth to hold the ladder base securely.

An important decision is where to position the tip of the ground ladder. This depends on what you want to accomplish after sizing up the outside of the fire building. If you want to vent as many windows as possible, place the ladder between two windows. If there is only one window to vent and it may explode outward from the force of an interior hose stream, an explosion, or fire, place the ladder to the side of the window. If your objective is to enter the window and conduct primary search, place the ladder at or below the window sill to facilitate victim removal.

WINDOW REMOVAL

Different circumstances warrant different venting procedures. In some instances the firefighter can quickly forceopen the window and vent the smokefilled room without breaking the glass. Or he can break the glass window and preserve the windowframe. At fires where building entry or victim removal is necessary, he may have to remove the glass and the entire window frame to provide access in and out of the smokefilled room. The firefighter may be ordered to vent an unoccupied building solely for purposes of removing smoke and heat, thereby assisting the advance of the interior attack team; in that case, a 6or 8-foot pike pole provides greater reach and safety. It allows him to operate further away from the window, reducing the risk of being blasted byscalding water from interior hose streams or thrown off the ladder from an explosion.

Cuts and other wounds to the skin comprise the second leading cause of fireground injury (the leading cause is strains and sprains). The outside vent firefighter often receives glass cuts and wounds from the windows he vents, those vented above him, and those vented from the interior. When you cannot open a window manually and must break it, stand to one side of the opening (the windward side, if possible), strike the glass with the pike pole at the top area of the window, and then work downward. If there is a possibility that firefighters are searching inside the room, first tap the window and only break a small portion of the glass—this will serve as a warning. Then remove the entire window with a tool. Keep eyeshields on helmets down for protection, wear gloves to protect your hands, and don’t stand in front of the glass window you are about to vent.

CUT OFF BY FLAMES

Firefighters venting upper-floor windows from the outside often must gain access to porch roofs, fire escapes, or the roofs of one-story extension buildings. Portable ladders provide access to these roofs or balconies. But when fire breaks out of a window and cuts off the outside venting firefighter from the portable ladder, he may be trapped on the roof or balcony. Such instances are occurring more frequently. At many fires, combustible liquids used by an arsonist, plastic furnishings, or air movements inside the burning structure create tremendous convection currents of flame out open windows.

A firefighter so trapped has a few options: He can wait until the fire is extinguished and then safely get back to the ladder, call for an additional ladder to rescue him, or perform some acrobatic feat to climb down from the porch roof or fire escape balcony. In any case, his entrapment disrupts the fire operation: Entry and search from that point will have to be suspended temporarily; the inability to perform the venting tactic could impede the progress of the interior attack team; it prevents him from performing other duties; or it takes his rescuers away from other important tasks.

Take precautionary steps to prevent such entrapment. When you need access to a porch or one-story extension roof, place the portable ladder on the windward side, if possible. When several windows require venting from the roof, vent the window farthest from the ladder first, working back to the window closest to the ladder.

Venting windows from a fire escape is more difficult. First, the ladder giving access to the fire escape balcony is in a fixed position. It may be on the more dangerous, leeward side of the windows about to be vented. Also, there is less room to work on a fire escape balcony compared with a one-story extension roof or porch roof.

Firefighters must stay low, crouched down, so flames and heat from a selfventing window can pass over them. Vent windows farthest from the fire escape ladder first, working back to the ladder when there is a serious fire and a danger of flame venting out the window.

Sometimes the fire escape serves a large burning room that has two windows, with only one served by the fire escape. Vent the window not served by the fire escape first. Lean over the balcony railing and use a tool that will give you some reach. If flames explode out of the window, they will relieve some of the heat and pressure in the room that might otherwise self-vent the window served by the fire escape.

OUTSIDE ENTRY AND SEARCH

Outside venting becomes more dangerous when there is a report of a trapped person inside the fire building. The venting firefighter still must locate the window to be vented —the one located at the opposite side of the fire from where the hose attack team advances. Only now he must vent and make an attempt to search the vented room and possibly other rooms behind the fire for trapped victims (if fire conditions permit).

After venting a window, if flames and smoke explode out of the upper portion of the window opening or if the room appears to be about to flash over, do not enter the flaming room. However, do not simply proceed to another assignment, either. Instead, crouch down low below the flames and attempt to sweep the area directly beneath the window sill inside the room with a tool or your gloved hand. Sometimes you will find people alive, slumped over each other, directly below the sill inside the flaming room. They collapse there after not having enough strength left to open the window or after calling for help from the partially opened window. If you are unable to enter after sweeping the area, try venting, entering, and searching adjoining rooms. Then after the blaze is extinguished, you can enter the room and complete thorough primary and secondary searches.

In some cases the flames are not in the room where you vented the windows but rather in an interior room. In this situation, the outside vent firefighter may enter the vented window, proceed to a door separating the fire from the back rooms, and close that door. The closed door acts as a flame barrier. The firefighter now can search the rooms and remove any victims. If there are no trapped or unconscious victims, the firefighter can, if fire conditions permit, reopen the door he closed before the search to provide a path of ventilation. He must then quickly retreat by way of the vented window.

FLASHOVER

Flashover is a state of fire growth in which the smoke-filled, superheated room suddenly bursts into flames. This can trap and kill outside venting firefighters who enter rooms to search. There are two warning signs of flashover: a buildup of heat inside a smokefilled room, and “rollover”—flashes of intermittent fire mixed with smoke either inside a room or as it flows out of a door or window. When a firefighter enters a smoke-filled room and finds very little heat mixed with the smoke, flashover is unlikely. However, if you are searching a smoke-filled room and have to crouch down to the lower half of the floor height to get below the superheated gases banked down below the ceiling, the room is in danger of flashing over.

In some instances, during a prolonged search inside a smoke-filled room there is little heat; however, after a period of time, heat builds up above the head of a firefighter who is crouched down below the smoke to increase his visibility during the search. During an extended search in a smokefilled room, raise an ungloved hand above your head into the smoke to check for heat buildup. If the heat intensity prevents you from raising your hand, put your glove back on and get out. Flashover could be imminent.

Rollover precedes flashover. When intermittent flashes of flame are mixed with smoke at ceiling level, flashover is about to occur. Unfortunately, because the first signs of rollover occur at the upper levels of the smoke-filled room, the outside vent firefighter crawling around the room searching for trapped victims cannot see them. So the buildup of heat is the only sign of flashover a firefighter inside the smoke-filled room can detect.

Outside, however, you can see rollover directly outside the window or door just opened for ventilation. If smoke flows out a window just vented at the upper levels of the opening, and you can see flashes of flame where the convection currents of smoke and heat are flowing, flashover can occur. Firefighters should not enter the room to search but should sweep the area below the sill, search an adjoining room through another window if possible, or enter the burning structure from another entry point and search the room after the fire has been extinguished.

After flashover occurs inside a superheated, smoke-filled room, there is a point of no return beyond which a firefighter cannot escape back to safety. When a room flashes over into flame, the firefighter is exposed to temperatures of 1,000° to 1,500° F, according to the “time-temperature” fire curve. Tests show that exposure to temperatures of only 280° to 320° F will cause extreme pain to all unprotected skin. The average speed of a crawling firefighter with 60 pounds of safety equipment is roughly 2.5 feet per second. A firefighter caught in a flashover 10 feet inside a room will be exposed to temperatures of 1,000° to 1,500° F at the neck area for approximately four seconds before he can escape out the window or door—that is, provided he can find it. Thus, the point of no return, or the maximum distance a firefighter can crawl inside a superheated, smokefilled room and still get back out alive after flashover occurs is only five or 10 feet.

Outside venting is an extremely dangerous task. It should only be given to an experienced, knowledgeable firefighter who understands the priorities of firefighting risk taking—that protection of life comes first. This includes the life of the outside vent firefighter as well as the trapped civilian. A firefighter only risks his life to save another life. He should make every effort to rescue a trapped person inside a burning building, short of becoming trapped himself. However, when fire conditions are severe, there is only a report of a trapped person, and he hears and sees no one, he is the number-one life priority.